Jack Arnold’s The Incredible Shrinking Man (1957):

Criterion Blu-ray review

in Jack Arnold’s The Incredible Shrinking Man (1957)

The technology of filmmaking has evolved radically since the first hand-cranked cameras of the Lumieres and Edison in the 1890s. Audiences greet each new development with amazement, but quickly come to take it for granted until the next new development makes the previous one seem quaint or inadequate. One of the greatest divides came with the rise of digital image creation, which quickly supplanted decades of refinement in physical and chemical techniques. Those who grew up with CGI often find older films unconvincing. As with silent films, they require a certain historical awareness to be appreciated on their own terms. For those of us who experienced the movies long before the advent of computers, reactions are to some degree mitigated by nostalgia. But a knowledge of older techniques can still inform our response to a movie made long ago, which is not to say that we have to make allowances or seek justifications for what may look crude or inadequate to eyes accustomed to slick, synthetic computer generated images.

Watching a film like Jack Arnold’s The Incredible Shrinking Man (1957) today is more complicated than it would have been five or six decades ago. Not only are the special effects dated; the movie emerged from a very different social environment. The story itself is simple enough on the surface that it can be experienced as an entertaining adventure, but as with many movies from the early years of the Cold War, it becomes much richer the more aware the viewer is of the time from which it emerged. This also applies to an appreciation of the technical work accomplished by Arnold and his collaborators.

If I seem to be belabouring an obvious point, it’s because I found myself occasionally irritated by some of the special features on Criterion’s new Blu-ray edition of the film, particularly Tom Weaver’s commentary track. Weaver has an enormous wealth of knowledge about filmmaking in the ’50s, especially genre and B-movies, having published many books and articles drawn from extensive interviews with actors, directors and technicians from the period. Yet he seems at times mocking, even derisive, about the film in regard to both the storytelling and the technical aspects of the production. Effects experts Craig Barron and Ben Burtt fare better in a featurette on the special effects and sound, providing detailed explanations of the complex technical challenges faced by the cast and crew, but even they occasionally find themselves excusing the visual flaws inherent in the optical effects.

When I watch (re-watch) a movie like The Incredible Shrinking Man, I first and foremost try to immerse myself in the narrative experience; the kind of commentary provided by Weaver, and to a lesser degree Barron and Burtt, works against this. Their perspective tends to reframe the film as an historical artifact rather than as a cinematic experience encountered on its own terms. While Criterion’s Blu-ray, mastered from a 4K restoration provided by Universal, gives the film its finest presentation ever on video, the extensive supplements (three-plus hours of documentaries, interviews and ephemera in addition to the commentary) paradoxically place it in a kind of museum display case. Has Criterion approached it as being too much of its time for someone raised on big franchise sci-fi and fantasy movies to appreciate on its own terms?

*

Richard Matheson’s 1956 novel The Shrinking Man uses the fear of radiation which hung over the ’50s as a device to trigger his exploration of other, equally deep fears of the period. On its face, that device is absurd – exposure to a combination of radiation and pesticides causes everyman Scott Carey to begin shrinking – but it serves as a potent metaphor for post-war anxieties about masculinity. These anxieties emerged as men who had been away fighting found it difficult to readjust to a society which had changed in their absence, most significantly in the ways that women had assumed a greater role through employment in war-related industries and were chafing at being forced back into a purely domestic sphere. Gender conflicts were inextricably woven through the political fears driving the Cold War, with Communism viewed to a degree as a feminizing threat to male authority. (In popular culture, this reached its apotheosis in the figure of the monstrous, castrating mother of movies like Leo McCarey’s My Son John, Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho and John Frankenheimer’s The Manchurian Candidate.)

The requirements of working to support a family were a far cry from the rigours of military life and combat; life back home was softer, more boring, rooted in responsibilities devoid of excitement. The post-war economic boom, the rise of suburban living, the routines of wage-earning and raising kids produced a new kind of insecurity, a need to redefine masculinity. This is the process Scott Carey undergoes, metaphorically, in both the book and the movie.

We get only a brief glimpse of the Careys “normal” life in the opening scene. The couple are relaxing on a small boat on a calm sea. Their banter is easy and affectionate, but it suggests well-defined gender roles: Scott (Grant Williams) takes for granted his dominant position, instructing Louise (Randy Stuart) to go below and fetch him a beer, which she does with just a suggestion of joking resistance. The irony is that it’s while she’s inside the cabin that a strange cloud drifts over the boat, leaving Scott covered with a glistening substance which is destined to alter his status irrevocably.

The first sign of change comes when he notices some time later that his clothes no longer fit him, seeming a couple of sizes too large. Louise jokes about him losing weight, but he’s troubled. Visiting his doctor, Scott is told that he is indeed growing smaller, though there’s no known explanation for his strange condition. He’s sent to specialists who run tests – and they tell him he’s been exposed to that weird combination of radiation and pesticides. But even with an explanation, nothing can be done.

At first Louise remains upbeat – this won’t change anything – but Scott knows they’re in for trouble, that as he grows smaller it won’t be possible to maintain a normal life. To confirm this, his wedding ring falls from his shrinking finger. The smaller he gets, the more bitter and resentful he becomes. Increasingly like an angry child, his petulance forces Louise into the role of a mother whose patience is wearing thin. Given the times, the subtext must remain unspoken, but is nonetheless obvious; Scott is no longer able to fulfill his sexual role in the marriage. (This is spelled out more explicitly in the novel, which even puts him at risk from a predatory pedophile.)

When a potential treatment seems to stop the shrinking process, Scott briefly has a relationship with Clarice (April Kent), a sympathetic midget from a carnival, but it doesn’t last as the temporary reprieve ends and he becomes smaller than her. Soon, he’s living in a dollhouse in the living room, reacting to Louise’s solicitous concern with irritation and resentment. Then one day, as Louise leaves the house, she doesn’t notice that the family cat has slipped back inside. Scott suddenly finds himself under siege by the, to him, giant creature. As it breaches the dollhouse, he manages to make it to the basement door, where a sudden gust of wind knocks him to the bottom of the stairs.

Having had his role as a man with a job and a wife stripped away, reduced to child-like dependency, Scott has at last been expelled from the domestic space. Relocated to a bleak new environment, dirty and littered with junk, he now begins to establish a new identity. With the requirements of his former social position gone, he focuses now on physical survival. This new life requires ingenuity and invention. Circumstances force him to become a primal man, scouring his world for food and water and, before long, he must confront a monster even more terrible than the family cat – living alongside him in the basement is a giant spider. But before his climactic battle with this creature, the boiler bursts and he’s almost washed away into a drain.

All these challenges redefine him as resourceful and self-reliant; beyond the constraints of a social life and a marriage, he is a man again, rugged and individualistic and beholden to no-one and nothing other than his own existence. Having defeated the spider and continuing to shrink, he faces this new existence with a kind of ecstatic joy, the closing narration conflating the microscopic with the infinite, himself with the universe. He has rediscovered the masculine meaning which suburban life in the ’50s had stripped away.

In light of the film’s trajectory towards this sense of joyous masculine liberation as a kind of adolescent fantasy of adventure, it seems doubly ironic that the studio pushed Jack Arnold to provide instead a “happy ending” with doctors finding a cure which restores Scott to normal size and reinstates him as a married man with a career. That, not his shrinking to sub-atomic size, would have been a nightmare for the character.

*

In The Incredible Shrinking Man, radiation is a convenient device, one much on people’s minds at the time, for triggering this exploration of male anxiety. In the first half of the film, as every aspect of Scott Carey’s socially dictated role, his obligations and responsibilities, is stripped away, he reacts with anger to the loss of identity. But in the second half, he rediscovers himself as a hero, an embodiment of masculine independence and authority, no longer beholden to Louise and meaningless work. In this, the movie is both an exhilarating adventure and a reactionary rejection of post-war society. It embodies the perennial urge to break away, to head out and explore undiscovered places where ordinary rules don’t (yet) apply. What he finds on his journey makes him forget what he once was and he embraces this new existence.

Whether inadvertently or not, Louise’s reaction to his departure suggests that there really wasn’t much for him in his former life. She expresses some guilt that her carelessness led to his apparent death, but he had become little more than an irritant in her own life. She simply accepts that he was eaten by the cat and moves away while he’s still fighting for survival down in the basement. For some time, he had no longer been a husband and partner in a shared life and she herself needs to move on. The traditional roles of husband and wife, with their clearly defined relationship to one another, couldn’t be sustained and they’ll both be happier now following their own paths.

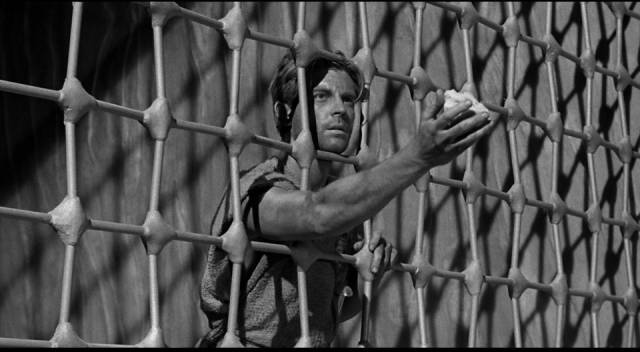

As with most of Arnold’s work, the film is well-directed, with Grant Williams and Randy Stuart handling their roles well as the characters’ relationship steadily deteriorates. The scenes between the now child-sized Scott and the increasingly maternal Louise are particularly good, the split-screen compositions executed with exceptional skill. The effects work is at its weakest in shots where Williams is composited into the image via travelling matte, his action shot on a black stage and laid over the scene. This technique is used mainly for the sequence with the cat and some shots out in the street and at the carnival – the latter exteriors seeming like an error in judgment as they could have been done with a child double, thus avoiding the obvious flaws in the mattes.

Of course, with CGI technology it would be possible to “correct” those flaws a la George Lucas, but this would erase the value of all these shots as indications of what was technically possible when the film was made. Flawed as they are, sequences like Scott escaping from the cat are ambitious and executed with obvious skill – even though the compositing can’t convincingly place Williams in the image, his action is effectively coordinated with that of the cat. In an interview with Arnold included on the disk, the director goes into detail about the process involved in getting the timing and framing right.

*

That interview with Jack Arnold is one of several excellent special features on the disk. Filmed in Arnold’s office at Universal in 1983 by German journalist Roland Johannes, it hasn’t previously been available in full until this edit (26:55) by Robert Fischer, which includes all the director’s remarks about The Incredible Shrinking Man. Arnold comes across as pleasant and very serious about his work, dealing with the film on a thematic level as well as with the technical challenges he faced.

There’s an interview (10:57) with Richard Christian Matheson, the author’s son, about the novel and his father’s feelings about the adaptation (initially not positive as Arnold ditched Matheson’s flashback structure to make the story linear), and a conversation between Joe Dante and writer/comedian Dana Gould, both fans of the movie (23:09).

As previously mentioned, Tom Weaver provides a commentary and Craig Barron and Ben Burtt discuss the visual effects and soundtrack (24:52), while music expert David Schechter talks about the score (17:13), which is a patchwork of library tracks and cues specifically written for the film by several composers. There are also a couple of 8mm home versions (16:24 combined), one with sound, the other silent with on-screen text, plus a 1959 episode of the long-running radio series Suspense called Return to Dust (18:56), in which a researcher tries to get help as he rapidly shrinks to microscopic size in the lab.

The longest extra (50:14) is an excellent overview of Jack Arnold’s career delivered by Weaver, Bill Warren, C. Courtney Joyner, Bob Burns and Ted Newsom, expanded for this release by director Daniel Griffith from a much shorter 2013 version.

There’s also a teaser narrated by Orson Welles (00:38) and a trailer (2:04). The booklet essay is by Geoffrey O’Brien.

Comments

Mr. Godwin,

I believe this is the finest review of this film I’ve ever read. It captures exactly how I’ve seen Incredible Shrinking Man over the years, but expresses it more completely than I’ve done in my own mind. The import of the narrative themes is spot on: and that force overrides any shortcomings in the technical achievements of the film viewed with today’s eyes, provided the vieweer can connect to the narrative’s human and cultural truths.

I can share that I showed this film to my 6-7 year old nephew on a big home theater screen at a time when he’d already experienced effects as good as “Honey, I Shrunk the Kids” (which had been released recently then). Andrew was totally captivated regardless. It was the power of the story that overrode everything else.

One thing I’ve realized recently–after reading that best-anyone-could-do biography of Grant Williams (very elusive to track in his personal life outside of his on-screen work)–is that his performance in this film is beyond good, for me. If you watch him closely in every scene he’s in, which is most of them, he’s “on” even when he’s the secondary focus of it, providing even just passive reaction. I don’t mean he’s

theatrically overdoing it (he’s not) but that he is clearly “in” every moment, living as if in the story for real. It’s no surprise that Giancarlo Stampalia’s biography notes Williams’ “method acting” training. The more I revisit this film now–I’ve just purchased the Criterion disc and will do so again, my third blu-ray version–the stronger it becomes for me. Truly the actor’s finest work.

But enough. Thanks again for capturing how I feel about this one-of-a-kind film.

Jeff

It’s always good to hear that kids raised on modern effects can still appreciate older films. I had a friend who ran a small theatre where he would run matinees of things like Ray Harryhausen fantasies to an enthusiastic response from kids who’d already seen things like Jurassic Park. Too many filmmakers think that technical “progress” trumps good storytelling.

Very good to hear. I’ve been a long-time Ray Harryhausen fan too, since childhood when I tried my own primitve stop-motion effects with a G.I. Joe.

Fantastic write-up. Glad I’m not the only one who found Weaver’s commentary somewhat tedious and annoying. As I’m listening to it, I’m thinking, “did you even like the movie??” Needless carping about the process photography, sneering at aspects of Williams’ performance. Surely there are enough other learned experts that would have jumped at the chance to do it. Anyway, I eventually had to switch off his track. But the wealth of other extras more than made up for it.

Looking forward to reading more of your posts. There look to be many great films here to discover and/or rediscover.

Back in the early days of DVD (and even before that with laserdisks), I listened to pretty much every commentary because they were relatively rare and were a genuinely “special” feature. As they became more common and all too often people weren’t putting a lot of effort into them, I became more selective – there just isn’t time to listen to everything. I was interested in hearing Weaver’s comments because of his work in gathering and preserving the history of Hollywood genre filmmaking in his many collections of interviews with actors, directors and others and I assumed he’d be bringing a wealth of detailed knowledge to the track here. What I didn’t expect was the snarky, dismissive tone. I did listen to the whole thing, though it really annoyed me, and was left wondering why he had bothered to make the effort. It’s a pity no one at Criterion challenged him on it at the recording session because it really adds a sour note to their otherwise excellent edition.