Columbia Noir 4 from Indicator

Indicator have been releasing their box sets of films noirs at a surprisingly rapid pace, with four volumes issued in just ten months, each containing six features and extensive extras. These, along with a varied schedule of other well-produced editions in numerous different genres, have made them one of the top companies over the past few years. Although they launched only four years ago, they’ve released more than three-hundred titles, all with excellent technical quality and plenty of new and archival supplementary content. Like Criterion, their dedication to film history is palpable; unlike Criterion, they embrace both high and low art with equal commitment.

Even though the noir sets draw only from the output of Columbia studios, the twenty-four titles released so far cover a broad range of the narrative and stylistic possibilities available under the large and rather loose umbrella of film noir – we get romantic melodramas, psychodramas, police procedurals and stories about the mob, all permeated with a sense of societal corruption and personal doom. The new set, Columbia Noir #4, is no different as it encompasses both documentary-style stories of political espionage and mob activity and more personal stories of morally compromised characters who make fatally bad decisions.

The set starts with two movies deeply rooted in the post-war Red scare, which place the FBI as heroic defenders of an America under imminent threat from foreign agents and domestic traitors. One was even based in part on a Reader’s Digest article by J. Edgar Hoover himself which was written to justify the executions of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg. But before that, there’s a movie which provides a bridge between wartime espionage and Cold War paranoia.

Walk a Crooked Mile (Gordon Douglas, 1948)

After a decade or so directing comedy shorts (many featuring the kids of Our Gang), Gordon Douglas graduated to B-movies like The Falcon in Hollywood (1944) and Zombies on Broadway (1945). Always a journeyman, he moved on to bigger projects in the 1950s and ’60s, with high-water marks like Them! (1954) and The Detective (1968). His no-nonsense approach (ironic considering those early comedy shorts) was well-suited to the gritty crime stories which flourished in the decade following the war. His movie about patrol car cops, Between Midnight and Dawn (1950), was included in the last Indicator noir set, and the new set opens with his Walk a Crooked Mile (1948).

Perhaps it was the lingering effect of wartime propaganda, but for a few years Hollywood produced quite a few pseudo-documentary crime movies which benefited from a lot of location shooting and a sombre, authoritative narrator who provided much of the necessary exposition about the operations of foreign agents and organized crime. While some of these techniques had been used for gangster films in the ’30s, the postwar movies tended to avoid many of the trappings of melodrama – there was a minimum of personal drama, with emphasis falling on procedures rather than individual psychology. This approach actually reached its peak on radio and television with Dragnet in the ’50s and ’60s, a show whose motto was “just the facts”.

In Walk a Crooked Mile, Dennis O’Keefe, who appeared in a number of these movies (he’s in two in this current set), plays Dan O’Hara, the agent in charge of security at a nuclear research facility in California who’s alerted by information from Scotland Yard that there’s a traitor on the base. Inspector “Scotty” Grayson (Louis Hayward) arrives from England to help root out the Commie rat and he and Dan start digging through the backgrounds of the scientists working on the project – an international bunch which, without overtly stating the fact, suggests that there may be more than one former beneficiary of Operation Paperclip, the plan which imported and made use of Nazi war criminals to help develop the U.S. nuclear and space programs.

The story by Bertram Millhauser and George Bruce completely glosses over the inherently fascist qualities of the American national security apparatus and makes it clear that the agents’ methods are necessary to fight the Communist menace. A cast full of good character actors keeps things lively as Douglas moves the story along at a tight pace. Raymond Burr in particular stands out as a cold-blooded enemy killer a decade before becoming a weekly symbol of moral rectitude as attorney Perry Mason in the long-running TV series.

Walk a Crooked Mile represents a transitional moment as wartime security concerns begin to give way to the ideological paranoia of the Cold War, providing a fairly entertaining time capsule which is given some atmosphere by the cinematography of George Robinson, who had shot more than a dozen Universal horrors, going back to George Melford’s Spanish-language version of Drácula (1931).

*

Walk East on Beacon (Alfred Werker, 1952)

Made four years later, Alfred Werker’s Walk East on Beacon (1952) is firmly embedded in the Cold War, not least for being adapted from that Reader’s Digest article attributed to J. Edgar Hoover. Not surprisingly, the FBI agents are stalwart and dedicated professionals as they track a network of foreign and home-grown Commie spies who are leaking scientific secrets out of the country. Although loosely based on the Rosenberg case, these secrets remain somewhat vague because Hollywood was committed to not giving anything real away. Here, the compromised project has something to do with the nascent space program rather than the Bomb.

While there’s little sympathy for the network involved in the leak, the scientist who is actually feeding them the information, Professor Albert Kafer (Finlay Currie), is treated kindly because he is the victim of blackmail – his son is a prisoner behind the Iron Curtain and will be killed unless the Prof cooperates. Agent Belden (George Murphy) and his team have to trace the path of the information from the lab, through a series of contacts to the people who finally get it out of the country, all while doing what they can to save the scientist’s son.

Once again, things are moved along by a stern narrator while the cast are limited to their functions in the story. Like Walk a Crooked Mile and most of these crime docu-dramas, Walk East on Beacon is “noir” only in its emphasis on the dark underside of postwar society (a few years earlier, Werker had made He Walked by Night [1948], a much more noir-ish movie about a cop killer); both films lack the psychological depth and sense of moral doom which hangs over the genuine noir anti-hero, but they illustrate the hardening of ideological attitudes which would continue to shape politics for the next four decades.

*

Pushover (Richard Quine, 1954)

Although best known for the comedies he directed from the mid-1950s to the mid-’60s, Richard Quine made a pair of fine films noirs in 1954. Drive a Crooked Road, starring Mickey Rooney (included in the first Indicator box set) was immediately followed by Pushover, which is notable for a couple of reasons. First, it has strong ties to noir through the casting of Fred MacMurray in the lead. Second, it was the movie which introduced Kim Novak, a twenty-year-old model whom Columbia hoped to establish as a rival to Marilyn Monroe. Although largely untrained, Novak displays real screen presence – vulnerable, but with an erotic power that’s more than sufficient to provoke cynical cop MacMurray to head down the path to corruption and murder. There’s more than a slight echo of MacMurray’s insurance investigator in Billy Wilder’s Double Indemnity (1944), but Novak is a very different femme fatale from Barbara Stanwyck’s mature schemer in that movie; in some ways, she’s more led astray by the cop than vice versa.

Novak plays Lona McLane, the girlfriend of a crook involved in a recent bank robbery. MacMurray is Paul Sheridan, one of the detectives on the case, who goes undercover to work his way into Lona’s life in hopes of finding the boyfriend. Although he’s playing a role, Sheridan can’t help but be attracted to her and when she eventually learns his true identity, initial resentment quickly turns into a mutual feverish madness as they decide to lure the boyfriend into a trap, eliminate him, and make off with the stolen money themselves.

Inevitably, their scheme doesn’t go smoothly. Not only does Sheridan have to kill the boyfriend; he also finds himself cornered by a fellow cop, a guilt-ridden alcoholic whom he kills, partly by accident, partly out of self-preservation. As mistakes and poor decision-making lead to increasing desperation, Sheridan’s partner Rick McAllister (Philip Carey) and boss Lt. Carl Eckstrom (E.G. Marshall) come to suspect what’s going on and close in on the doomed couple.

If Roy Huggins’ script (based on two novels) seems like formulaic noir, it’s tightly structured and directed with skill by Quine. The cast is excellent, with Novak radiating incipient star power, and there are a number of interesting touches – in particular the voyeuristic behaviour of the cops who set up in an apartment overlooking Lona’s windows. Echoing Hitchcock’s Rear Window (released just a couple of weeks after Pushover), McAllister begins to spy on Lona’s neighbour, a nurse named Ann Stewart (Dorothy Malone), his attraction to her instrumental in drawing her into the case and potential danger.

*

A Bullet is Waiting (John Farrow, 1954)

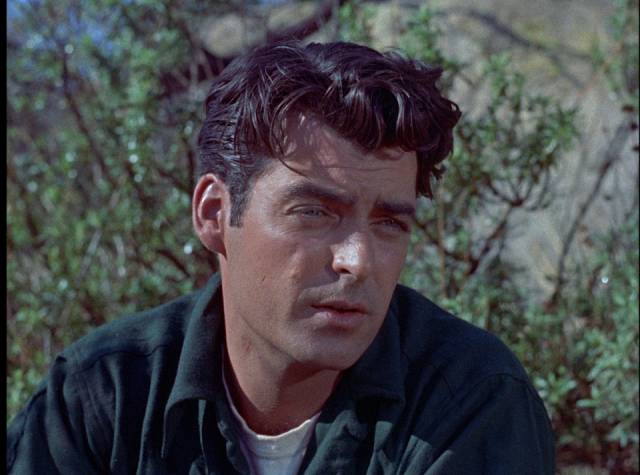

John Farrow’s A Bullet is Waiting (1954) is the odd one out in this set. Despite a contemporary setting, it has all the trappings of a western rather than noir, both in setting and visual style. Shot in dry scrubland in the California mountains, if we didn’t see a jeep and characters didn’t mention a crashed plane, there’d really be no way to tell that it wasn’t taking place in the Old West.

Director Farrow’s work was varied, with melodramas, war movies and westerns predominant. He had a few noir-adjacent productions, the best-known being The Big Clock (1948). A convert to Catholicism, Farrow wrote a number of books on Church history, a fact which to some degree influences the theme of redemption in A Bullet is Waiting.

As the film opens, two men climb from a rocky shore into barren hills; we know nothing about them other than that there is obvious enmity between them. They fight viciously before one of them manages to get away, running into a young woman and her dog. The woman is Cally Canham (Jean Simmons), who meets these two interlopers with suspicion. We eventually learn that she has been brought to this remote place by her father (Brian Aherne), a professor who has turned his back on the world and become a sheep farmer. There are obvious echoes of Prospero and Miranda, with the inexperienced Cally having to figure out the true nature of the two men who have arrived from the sea – to stretch a point, this pair take the places of Ferdinand and Caliban.

The younger, more attractive of the two is Ed Stone (Rory Calhoun), whom the other, Frank Munson (Stephen McNally), says is a fugitive murderer. Munson has been pursuing him for two years and, having finally found him, was flying back to Utah when their small plane crashed just off the nearby shore. Ed tells the story from a different angle. He did kill a man, but it was in self-defence. His victim was Munson’s brother, and the latter had himself deputized so that he could legally track Ed and get revenge. The Munsons are the richest family in the county, while Ed is lower status and believes he’ll never get a fair trial.

Cally has to weigh the two accounts and with Munson being aggressive and Ed being more attractive, she leans towards the latter. But when Ed heads off to find a way off the mountain and she follows, he attacks her, apparently attempting rape. Marking the film as from another time, little is made of this. She manages to ward him off and it isn’t mentioned again, and doesn’t prevent her from falling in love with Ed. The attempted rape plays no significant part in the narrative, seemingly there because such a scene was a common genre trope – men need to dominate, women need to resist and/or submit. Cally’s inexperience makes this just one more thing to weigh as she evaluates the two men, and in the end it plays no part in her decision to commit to Ed.

The power dynamics shift back and forth as the men wait for the weather to change so that they can leave, and Cally waits for her father to return from town. There are fights, more details about the history of Ed and Munson’s conflict, and the gradual inevitable development of Ed and Cally’s romance. She has committed to Ed by the time her father returns, but Prof. Canham has to make his own decision. He has hidden from the world because he wanted to wash his hands of the human tendency to self-destruction, but like Prospero, he knows that the time has come for his daughter to re-engage with the world. So, having suggested that Ed should go back and face the consequences of his actions, he lets the two men their their violent conflict to whatever conclusion fate dictates.

Munson is determined to kill Ed, but at the crucial moment Ed makes a moral choice; he’s not a killer by nature, and even though he’s again fighting in self-defence he chooses to eschew violence. All four characters climb into the Jeep and head off the mountain towards the messy but unavoidable world where decent people willingly accept responsibility for the things they have done.

Shot in colour on arid mountain locations, there seems to be very little noir in A Bullet is Waiting. It has the feel of the psychological westerns which were transforming that genre in the ’50s – movies by people like Anthony Mann and Budd Boetticher – with a touch of the morality play in the character arcs of Ed and Cally in particular. Farrow efficiently builds and sustains dramatic tension with, for most of the running time, just three characters in a single location, and the cast all give solid performances, though Simmons feels a little out of place with her delicate features and obvious Englishness – the script was actually revised to explain the latter, making her and her father English, the Prof having fled as far as possible from their old life.

*

in Fred F. Sears’ Chicago Syndicate (1955)

Chicago Syndicate (Fred F. Sears, 1955)

Producer Sam Katzman and director Fred F. Sears had a prolific relationship making B-movies together, predominantly westerns though their output included sci-fi and horror as well as an occasional noir. Chicago Syndicate (1955) resembles the docu-noirs, though without the detachment of an omniscient narrator and with more melodrama. One of the amusing aspects of docu-noirs dealing with organized crime is that they provide space for accountants to be heroes. Glenn Ford spends much of Joseph H. Lewis’s The Undercover Man (1949) in a small room going through piles of ledgers. Dennis O’Keefe is a bit more active in Chicago Syndicate as accountant Barry Amsterdam who’s persuaded by the authorities and a newspaper owner to go undercover to find evidence against mobster Arnie Valent (Paul Stewart).

Valent’s previous accountant was murdered in a very public way after he decided to go to the cops with what he knew, so Barry approaches the mobster with a story about having witnessed the hit and being able to identify the trigger man. He asks for the dead man’s job in exchange for keeping quiet. Valent is understandably suspicious, and puts Barry to the test. Eventually satisfied, he does take Barry on, gradually revealing details of the criminal activities concealed behind his supposedly legitimate insurance interests.

Complicating things are Sue Morton (Allison Hayes), who turns out to be the murdered accountant’s daughter, doing her own investigating, and nightclub singer Connie Peters (Abbe Lane), Valent’s mistress, who drinks too much and becomes increasingly jealous of Sue. She makes the mistake of revealing that she’s in possession of microfilm of Valent’s books which Sue’s father left with her – after a vicious beating from Valent’s men, she gets the evidence to Barry as the mobsters close in for a climactic shoot-out.

Chicago Syndicate is a tight, efficiently made little B-movie, which by 1955 already seemed a bit dated, though that didn’t stop Katzman, Sears and O’Keefe covering similar ground the next year with Inside Detroit and Miami Exposé before the producer-director pair launched their run of ’50s rock-and-roll, horror and sci-fi movies.

*

in Phil Karlson’s The Brothers Rico (1957)

The Brothers Rico (Phil Karlson, 1957)

The set ends with a tough character study adapted from a novel by George Simenon and directed by Phil Karlson, whose previous feature was his masterful The Phenix City Story (1955). Once again the protagonist has an accounting background. Eddie Rico (Richard Conte) retired from his mob job and is now a respected businessman with his own successful laundry company. A seemingly decent man, he is a little naive about his relationship with the criminals he once worked for, particularly Sid Kubik (Larry Gates), who is almost like an uncle, having watched over and helped the Rico family since Eddie and his brothers were kids.

One day Eddie gets a call from Sid about a problem that needs to be dealt with quickly, a problem which requires finding out where brothers Johnny (James Darren) and Gino (Paul Picerni) have disappeared to. Eddie has to put his life on hold while he tries to track his younger siblings down – including delaying the adoption of a baby he and his wife Alice (Dianne Foster) have been working towards for a long time. For Eddie, it’s not possible to say no to Sid, whom he owes a great deal, even if it puts a strain on his own marriage.

His search for Johnny and Gino takes him half way across the country and what he learns along the way undermines his complacent assumptions about having made a decent life for himself disconnected from his criminal past. By the time he realizes that he has been used to expose his brothers so that Sid’s men can kill them, it’s too late to salvage his self-image (although a tacked on “happy ending” attempts the task). Although Eddie is a bit implausibly slow in figuring out what’s going on, his brothers’ continuing mob activity reveals that his escape has really been illusory, that Sid has allowed it and has the power to take everything away again.

As always, Karlson imbues the material with a tough realism, although there’s more melodrama here than in The Phenix City Story. Apparently the script by Lewis Meltzer and Ben Perry softens Simenon’s novel quite a bit, but the movie, like the later Godfather (1972), shows how family and business are inextricably interwoven in organized crime, with business always destined to outweigh family ties.

*

Needless to say, Indicator’s presentation of these six movies is exemplary, with each film looking terrific in Sony’s new hi-def transfers. Five of the films get commentaries (Walk a Crooked Mile is the exception for some reason). There are several March of Time shorts focused on the FBI and police work, and discussions of Richard Quine and Kim Novak (by Glenn Kenny), Jean Simmons (by Josephine Botting) and Phil Karlson (by Nick Pinkerton). Each disk as usual also includes a Three Stooges short, plus there’s a 120-page book of essays, interviews, contemporary articles and promotional materials. While some of the movies in these sets are minor, the sets themselves are an essential addition to the history of film available on disk.

Comments