September Arrow releases

Is it a sign that I’ve been writing this blog for too long? Or a more disturbing indication of mental decline? It’s been eleven years, almost eight-hundred posts, 1.5+ million words. I had no idea when I started this as a casual diversion in October 2010 that I’d still be doing it more than a decade later … or that it would end up being so extensive that I’d forget much of what I’d posted.

This particular entry began as a review of Arrow’s new Cold War Creatures box set of four cheap mid-’50s sci-fi/horror B-movies produced by Sam Katzman. After several hours of writing, having got through half the set, I was checking something on the site (had I previously written anything about prolific journeyman Edward L. Cahn, who directed two of the movies in the set?) and discovered that I’d actually reviewed the earlier DVD version of these movies released in 2007 as Icons of Horror Collection: Sam Katzman. So I quickly reread that post from December 2015.

I sometimes look back at what I’ve written in the past and surprise myself – I don’t think I could write that particular review or essay again today; it’s almost as if these are somebody else’s words. The surprise in this particular instance was discovering that what I’d just been writing was not only structurally the same as that earlier post, but that I was making exactly the same points, repeating details and observations in almost identical words. The biggest difference was that the 2015 version was much more concise … have I just become more verbose, or is there more depth and nuance in my writing today? I’d like to think it’s the latter, but fear it’s the former.

I debated with myself briefly about whether or not to continue with the Cold War Creatures review, but it just seemed redundant – and in a way, reading the old post kind of contaminated my train of thought. I will say that Arrow’s Blu-rays look excellent, with strong hi-def transfers supplied by Sony. Not only has detail and contrast improved, there’s also been some clean-up which repairs damage previously visible in the stock footage which pads the running time of The Giant Claw. Each movie gets an introduction by Kim Newman and a commentary, with each disk containing a featurette which doesn’t deal with that specific film, but rather with more general points about Katzman and his productions: the longest, on the first disk (Creature with the Atom Brain, 1955), is a discussion of the producer’s work by Stephen R. Bissette copiously illustrated with original promotional material; the second disk (The Werewolf, 1956) has a discussion by Alexandra Heller-Nicholas about the position of women in these movies, which both reiterate and push against genre stereotypes of the period; disk three (Zombies of Mora Tau, 1957) has critic Josh Hurtado talking about the intersection of horror and science in creature features; and disk four (The Giant Claw, 1957) has critic Mike White discussing monsters as a metaphor for Cold War paranoia.

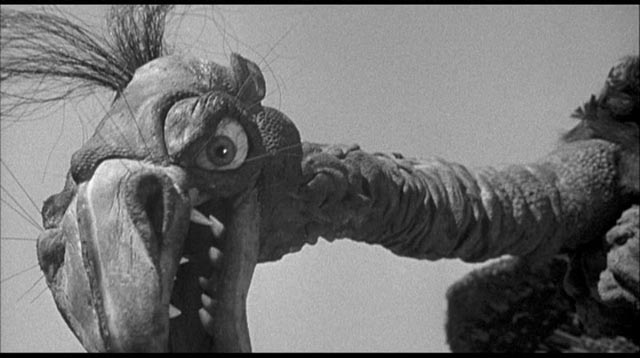

The set also has two nicely produced books, one with essays on the individual movies, the other a print reiteration of Bissette’s featurette in which he writes a brief introduction to a collection of each movie’s promotional art. All in all the set is a lavish showcase for these threadbare B-movies and it was fun to revisit them, particularly the two directed by Fred F. Sears. The Werewolf is the best of the four, benefiting from location shooting and a really good performance by Steven Ritch as the hapless victim of a pair of unethical doctors; and The Giant Claw, so often derided as one of the worst movies ever made, has an absurd charm which grows with each viewing – the ridiculous puppet and shoddy miniatures are a wonder to behold and far more entertaining than the supposedly better effects found in movies like Nathan Juran’s The Deadly Mantis or Bert I. Gordon’s Beginning of the End (both also 1957).

*

So, with my planned post sidetracked, I’ll move on to a couple of other new Arrow releases which I watched under perhaps less than ideal circumstances – my friend Steve came over and we ate a lot of pizza and drank some strong beer, which made me sluggish, and chatted through both features. If my attention was less focused than it should have been, it was a pleasant break from continuing pandemic isolation. And the pizza and beer were really good…

The Brotherhood of Satan (Bernard McEveety, 1970)

I wrote briefly about Bernard McEveety’s The Brotherhood of Satan (1970) when I saw it for the first time back in May 2020 on a Mill Creek double-feature Blu-ray. Needless to say, the Arrow disk is a huge improvement. The image looks pristine, with fine detail and contrast, and rich saturated colours; it could’ve been shot yesterday. I have no idea how I missed this movie on its original release as it’s definitely something which would have appealed to me back in the day; perhaps it simply didn’t play in Newfoundland, where I was living at the time – given that churches had quite a lot of sway there, perhaps Satanism was kept out of theatres? There was certainly no problem with access in Winnipeg a few years later to similar movies, such as Jack Starrett’s Race with the Devil and Robert Fuest’s The Devil’s Rain (both 1975). In this respect, McEveety’s movie was slightly ahead of its time and stands as one of the best in this genre.

Widowed Ben (Charles Bateman), his daughter K.T. (Geri Reischl) and girlfriend Nicky (Ahna Capri) are on a road trip in the Southwest when they see wreckage from a strange “accident” at the side if the road – a completely crushed car from which a bloody human foot protrudes. We viewers already know something unnatural is going on because the movie opened with a kid’s toy tank transforming into a full-size Sherman which crushes a car as its inhabitants scream. Ben drives into the nearby desert town to report what they’ve seen, but they’re inexplicably attacked by the locals, barely getting away. They don’t get far, however, because a girl standing in the road causes them to swerve and hit a telephone pole. Options are limited – walk into the desert in hopes of flagging down a car, though they’ve seen no one else on the road, or go back into town looking for help.

Reluctantly doing the latter, they begin to realize that some strange force is keeping them trapped in the town. They also discover that the initial hostility they encountered is due to a series of child disappearances over the past few days. The sheriff (L.Q. Jones), his deputy (Alvy Moore), the local priest (Charles Robinson) and doctor (Strother Martin) are desperate and exhausted, reluctant to admit that something supernatural is going on (the deputy suggests that maybe it’s aliens). We eventually learn something the characters remain unaware of; the town is in the grip of a Satanic coven led by the doctor and they’re preparing to transfer themselves into the bodies of the kidnapped children to prolong lives which may already be centuries long.

The first half of the film is creepy and unsettling as it deals with uncertainty and increasing paranoia; the second half, after the big reveal, concentrates on the activities of the coven and the desperate efforts of Ben, Nicky, the sheriff and deputy to uncover and put a stop to those activities. The movie is steeped in atmosphere, McEveety’s staging making excellent use of cinematographer John Arthur Morrill’s widescreen frame. Score composer Jaime Mendoza-Nava’s next assignment was another favourite, John Hayes’ Grave of the Vampire (1972). Producers/co-stars Jones and Moore re-teamed four years later for A Boy and His Dog (1975); it seems puzzling that these two movies didn’t lead to others, but both of them returned to lengthy acting careers, never producing again. (They did have two previous producing credits, Jones’ The Devil’s Bedroom [1964] and William O. Brown’s The Witchmaker [1969].)

*

Death Screams (David Nelson, 1982)

The other movie Steve and I watched was more obscure; Death Screams (1982) is an early ’80s slasher made in North Carolina, shot in part at EO Studios, which had been established as a full production facility by local entrepreneur Earl Owensby in the 1970s, who pushed to make the state a viable location for production before Dino De Laurentiis established his studio in Wilmington in the early ’80s. Ohio-born producer Charles Ison teamed up with Ernest Bouskos, a West coast owner of grocery stores, and commissioned a script from writer Paul C. Elliott. Initially aiming for a comedy-fantasy, energies were soon redirected towards a horror movie and David Nelson was hired to direct, with former Playmate of the Month Susan Kiger cast for “name value”. All this seems fairly standard for a low-budget regional independent, but there are some interesting oddities.

Producer Ison had been involved in television production, mostly in music and variety shows, as was writer Elliott, who worked on a mid-’70s series starring Dolly Parton, while director Nelson was the son of Ozzie and Harriet Nelson and had been a juvenile actor on the family sit-com throughout the ’50s, taking on directing chores in the early ’60s. It seems incongruous that these three should have taken on a slasher movie at the height of that genre’s popularity. Perhaps not surprisingly the results are awkward and the movie disappeared after a brief release and video distribution, resurfacing now thanks to Arrow’s apparent commitment to unearthing every slasher movie made in the ’80s.

The first thing to note is that what appears on the disk is a far cry from the pristine transfer of The Brotherhood of Satan. The only available source was a faded and battered theatrical print borrowed from a private collector. While Arrow seem to have made heroic efforts to salvage the movie, daytime scenes tend to be washed out, with weak colours, while night scenes (the bulk of the movie) are often murky and lacking in detail. The acting is about as uneven as the imagery. It’s probably a good indication of how mismatched the production team were for the material that the best sequence is the equivalent of a kids’ campfire tale told towards the end in a cemetery at night. Lily (Kiger) is pressed into telling a scary story, which she actually does very effectively in a scene which takes its time, simply and atmospherically shot, suggesting that everyone involved might have done better to make a comfortably scary movie for kids.

Because the elements aimed at an older audience are very clumsily handled, with most of the killings either off screen or shot obliquely to obscure what’s happening. In the opening scene, a young couple are parked by a river making out (awkwardly) on a motorcycle. Some kissing, a glimpse of bare breasts, and then suddenly they’re attacked. Steve and I tried to figure out the mechanics – the guy spits blood, the bodies are dumped into the river seemingly pinned together, so we speculated whether they’d been harpooned like the teens impaled during sex in Friday the 13th Part 2 (1981). But in the essay in the booklet with the Arrow disk Brian Albright mentions in passing that they were strangled. That’s definitely news to me.

While some of the other deaths aren’t as obscure, Nelson deliberately cuts away at crucial moments. Even though there’s a sudden frenzy in the last few minutes, very little tension has been generated and the abrupt reveal of the killer’s identity comes out of nowhere. Nothing has been established to prepare for this and we’re left wondering just what his motives are. Since there’s only been one very weak red herring until then, the whole thing falls flat.

Paradoxically, we did find other aspects of the movie at least a little bit entertaining. In particular the really poorly structured script leads you to find something other than the murders to focus on. After that opening attack, we’re introduced to the inhabitants of the small town at a kids’ baseball game … then at a diner … then at a grocery store and a gas station. There are a lot of characters and it takes some effort to keep track of them; a couple of kids home from college, who are tentatively beginning a relationship; Lily who works at the diner and her crusty grandma; the school baseball coach, who’s attracted to Lily, who in turn seems the least interested of the young women trying to hit on him; the sheriff and his mentally challenged son, whose backstory we eventually learn (he was apparently brain damaged during a prank gone wrong, making the sheriff unsympathetic to the other kids)…

After this long introductory stretch, we are introduced to them all over again as they go to a carnival visiting the town. We don’t actually learn much more about any of them; the movie just seems to be hanging out with them. The carnival section ends with one girl walking away only to be shot through the neck with an arrow. She stumbles back to what now seems to be a deserted carnival and collapses against a horse on a carousel which begins to move as a plastic bag is pulled over her head to finish her off. No one subsequently refers to her death and apparently the sequence was shot after the fact when someone realized that we’re well into the running time and nothing much has been happening. It’s all very slapdash, with little sense of how a story – particularly a generic story like this – needs to be told.

The gore was handled by Worth Keeter, who had provided makeup effects for Frederick R. Friedel’s Axe and Kidnapped Coed and J.G. Patterson’s The Electric Chair. It’s functional, though we only get glimpses. Perhaps most surprising is that the score is by Dee Barton, the jazz musician who in the previous decade had scored Clint Eastwood’s Play Misty for Me and High Plains Drifter and Michael Cimino’s Thunderbolt and Lightfoot. Here, his music almost overwhelms the movie as if he’s trying hard to pump some energy into a pretty lethargic thriller.

*

Both movies get commentaries (two for Death Screams), there’s a new making-of for Death Screams and a video essay about Satanic movies plus an interview with two actors who appeared as kids in Brotherhood.

Comments