Ghosts, Monsters and Swordplay

Martial arts movies are often a form of fantasy, with performers defying the laws of physics in impossible acrobatic displays which simultaneously imbue human bodies with weightlessness and supernatural power. So it’s not too surprising that such movies quite frequently tip over into outright fantasy. In Chinese filmmaking, this means setting martial arts contests in a fantastic realm of spirits and gods, particularly in the wake of Tsui Hark’s Zu: Warriors from the Magic Mountain (1983). In Japanese cinema, filmmakers drew on a long and rich history of folklore in which spirits and monsters existed everywhere beside human beings. In these movies, the supernatural isn’t a disruption of the natural order but rather an integral part of it.

Yokai Monsters (1968-69/2005)

Just over a year after the great commercial success of the Daimajin trilogy, Daiei aimed to repeat that success with another trilogy. Like the Daimajin films, the Yokai movies were given a firm foundation in the studio’s well-established line of period productions in which peasants live hard lives at the mercy of heartless landowners, masterless samurai and criminals. This is the milieu of Daiei’s long-running Zatoichi series and in fact some of these fantasies would work just as well with the supernatural element replaced by the blind masseur.

Although both trilogies were written by the same scriptwriter, Tetsuro Yoshida, there are some notable differences. All three Daimajin movies have the same narrative structure, giving them a limited range in terms of theme and action – peasants are oppressed by their vicious social superiors until life becomes unbearable, at which point they call on the god Majin to free them. Despite each film being made by a different director (Kimiyoshi Yasuda, Kenji Misumi, Kazuo Mori), they have a sameness which produces diminishing returns despite the excellent effects work of Yoshiyuki Kuroda and his team at the Daiei Kyoto studios.

The Yokai trilogy, however, was the work of Yasuda and Kuroda in collaboration, and yet each film has its own distinct flavour. While the supernatural creatures are similar across all three films, the tone and narrative focus changes with each episode, sustaining a sense of creative possibilities. The first and third films, 100 Monsters (1968) and Along with Ghosts (1969), are the most satisfying (for me at least) because they remain firmly rooted in the familiar Edo period world, while the second film, Spook Warfare (1968), aims at much more overt fantasy-horror.

100 Monsters (dir. Kimiyoshi Yasuda, SFX Yoshiyuki Kuroda, 1968)

The first film quickly establishes a thriving village community, crowded, lively, with people greeting one another and bantering cheerfully. But this morning is suddenly interrupted by an arrogant man leading a team of tool-bearing workmen. He declares that they are here to tear down the small, shabby shrine and the villagers’ tenement housing because their boss, a corrupt businessman who plans to build a brothel, has claimed the deeds from a local man who owes a debt he can’t pay. When the caretaker tries to stop them, these men beat him to death. The desperate villagers plead with a ronin staying in the tenement but he just tells them not to bother fighting the inevitable.

The businessman, putting on a feast for a corrupt magistrate, provides entertainment in the form of a storyteller who is to relate one-hundred ghost stories. After each one, a candle is snuffed out, and after the final candle is put out a ritual must be performed in order to ward off the spirits which have been aroused by the stories. However, the businessman doesn’t subscribe to such superstitions and after the storyteller is finished, he conducts his own “ceremony” by giving each guest a bundle of gold coins, buying everyone’s loyalty. Needless to say, this turns out to be a mistake, as some of the guests are accosted by spirits as they make their way home, their scattered gold ending up in the local pond.

Among the guests, the ronin has sneaked in and he hands his bundle of gold over to the villager so that he can pay off his debt and save the tenement. But the businessman’s henchmen kill the villager and the businessman denies having been paid back, ordering that the demolition go ahead. The dead man’s daughter submits to pressure to give herself to the corrupt magistrate, only to find herself a prisoner and the promise that her submission will save the community reneged on. Luckily, the ronin shows up to rescue her and the aggravated spirits finally attack those who have offended them.

As mentioned, this situation could have been resolved by Zatoichi. But the spirits add a whole other level of charm. Quite early, the businessman’s simple-minded son finds his interest in a particular spirit – a one-eyed, one-legged umbrella with a long tongue, which the boy draws repeatedly on the walls – rewarded when his drawings come to life and the monster plays with him affectionately. A couple of others, particularly a woman whose neck can stretch out to fantastic lengths, appear during the storyteller’s performance at the feast. But for the most part, as in the Daimajin movies, the creatures really only show up in the final act when they launch their attack on all the bad guys.

Here there are some terrific visuals, like the gigantic head of the slit-mouthed woman looming above terrified henchmen in the woods, and the big crowd scene in which the gathered monsters surround the businessman in his home, driving him to madness. The monsters, reacting to having been offended, manage to restore order to the community, while the ronin finally reveals himself to be a representative of a higher authority sent to root out corruption.

Spook Warfare (dir. & SFX Yoshiyuki Kuroda, 1968)

That sense of community is missing from the second film, which begins far from Japan as a pair of English tomb raiders look for treasure in Babylonian ruins, their greed inadvertently freeing a demon (named Daimon) which has been sealed beneath a statue for thousands of years. Daimon flies off to Japan, becoming a malevolent foreign invader who’s an affront to the local spirits. This giant, birdlike monster has a taste for human blood and the ability to take possession of its victims – the first of whom is a benevolent local magistrate who suddenly becomes an angry, vindictive man who despises all the paraphernalia of his family’s religion, smashing the household shrine and ordering that everything should be burned.

Daimon’s arrival was witnessed by a kappa, a water spirit, who tries to convince the other Yokai that there’s a threat to be faced. Not only are the Yokai introduced right away, unlike in the previous movie they are extremely talkative and played for comic effect. This deflates the air of mystery they possessed in 100 Monsters, and makes Spook Warfare seem much more like a movie for kids. They may have a lot more screen time, but this time out they seem less magical. This is no doubt a matter of personal taste – there are many commenters who dislike the emphasis on the human story in the first film and prefer the more prominent fantasy elements in the second – but to me they seem diminished. Daimon is quite impressive, but with the human characters more or less in the background, trying to figure out what’s going on, the Yokai’s fight against Daimon seems more simplistic.

Along with Ghosts (dir. Kimiyoshi Yasuda & Yoshiyuki Kuroda, 1969)

The third movie gets back to the “real” world with the story of a young girl whose grandfather is murdered by gangsters and has to go on the road in search of the father who abandoned her at birth when her mother died. The gang believe that she possesses a document they want and pursue her, while various people along the way help or hinder her to various degrees. Again, this is a Zatoichi-ready narrative, with the child having to figure out who she can trust among the various rootless characters she encounters. It’s no surprise to learn eventually that one of the men on her trail is actually her lost father, a gambler and criminal who is at last given an opportunity for redemption.

So where do the Yokai come in? Hardly at all this time out, and certainly not in the familiar, distinctive forms seen in the first two films. This is closer to a traditional Japanese ghost story, with a curse falling on the gang because they have killed on sacred ground – the grandfather was caretaker of a small shrine at the place they have chosen to ambush a man carrying the document they’re after. There are a few brief ghostly manifestations along the way, with a sudden crowded onslaught at the climax, but again these seem more like traditional ghosts than the idiosyncratic creatures of the other movies. Perhaps, as some commenters have speculated, Along with Ghosts was drafted into the Yokai “trilogy” after the fact.

That said, I enjoyed the film for its familiar genre elements. The character types – gangsters, gamblers, masterless swordsmen – and the road movie narrative are pleasing in themselves, with the supernatural touches adding extra atmosphere. I guess it all depends on what you’re looking for, and I’m quite happy to spend some time in this particular cinematic world.

*

These three movies are contained on two disks in Arrow’s new Yokai Monsters Collection box set, each film getting a vibrant, colourful hi-def transfer. Extras are rather light – no commentaries – with the first disk including a forty-minute featurette in which various experts (only one of whom is Japanese) sketch the history of Yokai in Japanese folklore and entertainment.

in Takashi Miike’s The Great Yokai War (2005)

The Great Yokai War (Takashi Miike, 2005)

But the box set doesn’t stop there as it also contains, in its own case, Takashi Miike’s The Great Yokai War (2005), which brings the mythology out of the trilogy’s period past into the present and a kind of steampunk apocalyptic future. For those disappointed by the restrained fantasy of the older movies, Miike provides an excess of action and effects and vast hordes of Yokai monsters.

In a small seaside town, Tadashi (Ryunosoke Kamiki), a young boy living with his forgetful grandfather after his parents’ divorce, is bullied by the local boys. At a festival, a dancing dragon tags him as this year’s Kirin rider, a kind of guardian who legend has it must climb the local mountain to a goblin’s cave and retrieve a magic sword to protect the town against supernatural threats. Lured onto the mountain, he encounters odd manifestations and flees in fear. On the way home, he finds a timid little creature with an injured leg, kind of like a spirit guinea pig.

We’ve already met this critter, having seen it barely escape from Agi (Chiaki Kuriyama), a menacing figure working for Kato (Etsushi Toyokawa), a figure consumed by anger at the way modern Japan has destroyed the ancient land populated by spirits. He has sent Agi to capture all the remaining Yokai, whom he throws into a giant furnace along with all the industrial detritus of the society he despises, transforming them into living machines which he is building into an army to destroy the human world.

Tadashi finds himself unwillingly in the position of the human champion who must stand against Kato and Agi in a war which threatens to consume both the human and spirit worlds. His allies and helpers are the Yokai who resist absorption into Kato’s army. Here we find all the familiar figures and many new ones – kappa, the long-necked woman, and one who’s obsessed with his pot of azuki beans, which he washes and counts incessantly. Those beans turn out to have surprising power at a crucial moment.

The Great Yokai War is big and loud, with references going back to the original movies as well as nods to the likes of Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981). Apart from the early scenes, it mostly takes place in a purely fantasy world in which a few intrepid characters stand up against a hugely powerful enemy … who, despite doing some pretty nasty things, does have a legitimate point. It’s just that his solution to human wastefulness and the destruction of the natural world is so sweeping and destructive itself that it’s wreaking havoc on the supernatural creatures whose loss inspired his anger in the first place.

The Blu-ray has a commentary by Tom Mes, plus a stack of archival extras – interviews, conferences, a few short films (one particularly amusing as a couple of cops interrogate the kappa, whom they have picked up on the street), and a short documentary about the film’s young star.

The set also includes a 60-page book with essays on the trilogy and the place of Yokai in Japanese culture, plus a chart identifying several dozen Yokai. All in all, an excellent companion to Arrow’s recent Daimajin box set.

*

Duel to the Death (Ching Siu-tung, 1983)

Duel to the Death (1983), the solo directorial debut of experienced action director Ching Siu-tung, comes from a very different tradition. A common focus of Chinese martial arts stories is the rivalry between different schools, each teaching its own proprietary techniques (the most famous probably being Shaolin Temple). While there are often specific historical references and political intrigues, the main point is the honour of the schools and their desire to prove their superiority over all others. Ching’s movie enlarges on this by making it a question not just of a school’s honour, but rather the honour of the nation.

Every ten years, China and Japan choose a master swordsman for a ceremonial duel to determine which nation’s martial arts is the best. This year, the Chinese champion is Ching Wan (Damian Lau), a Shaolin scholar given more to philosophy than combat, while the Japanese representative is Miyamoto Ichiro (Norman Tsui), whose greatest ambition is a noble death. This difference in national character becomes subsumed to a complex plot to subvert the duel and secure Japanese dominance in the martial arts world.

Japanese envoy Kaneda (Eddie Ko Hung) has a plan to kidnap all the Chinese masters who are on their way to witness the contest and take them back to Japan, where they will be forced to divulge the secrets of their individual schools. He is aided in this plan by Master Han (Paul Chang Cheung), at whose school the duel is scheduled to take place. He is embittered because he own school, once a source of champions, has declined in reputation. In his desire to be on top again, he conspires with the Japanese to decimate the Chinese schools.

The nefarious scheme is in the hands of a band of deadly ninjas, who we first see breaking into a temple to steal treasured martial arts texts. As Ching and Miyamoto uncover the plan, they join together to defeat Kaneda and his ninjas, aided by Sing Lam (Flora Cheung), a skilled swordswoman who makes her initial appearance disguised as a man. This is a common trope in wuxia, going back to the genre’s origins in opera and never very convincing on film (Brigitte Lin played such roles a number of times, her striking beauty demanding that the audience simply go along for the sake of the story).

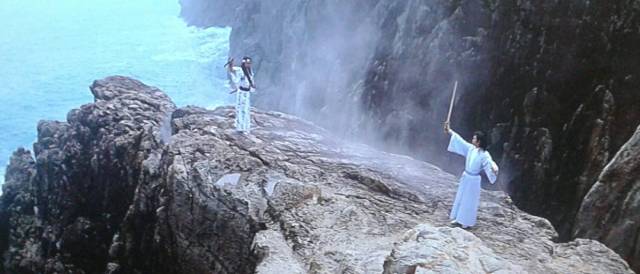

Although King Hu had given his characters the illusion of flight in the early ’70s, Ching here pushes the gravity-defying acrobatics to new lengths in a series of spectacular sequences between the heroes and the ninjas, who seem to be imbued with supernatural powers. At times, the ninjas plausibly fly using large kites; at other times they levitate under their own power. And at yet other times, they can travel under the ground, bursting up to confront their opponents and, when the tide seems to be turning against them, literally exploding, killing themselves and those they are fighting. In one remarkable scene, a monk is pursued by a giant ninja which suddenly bursts apart into a whole squad who attack from every side.

Apparently audiences at the time weren’t sure what to make of all this and the film wasn’t a commercial success despite its many fine qualities – the excellent cast, gorgeous photography which provides one striking image after another, and the remarkably elaborate fight choreography. It was also released at an inopportune time as China and Japan were trying to work out fraught issues dating back to the war and the Japanese occupation, making the story’s contest between the two nations and the underlying schemes and betrayals problematic.

But perhaps another reason for the cool reception and subsequent low profile of the film is the downbeat ending. Although the action is exhilarating, by the time Ching and Miyamoto have defeated the bad guys’ nefarious plans, the idea of a duel to “prove” something about the two countries’ relative values seems pointless. Ching, for whom competition is something of a waste anyway, suggests that they abandon the duel. Miyamoto, however, remains deeply invested; triumph or death are the only options which hold any meaning for him, not for the honour of his country but purely on a personal level. And so he does something cold-bloodedly vicious to provoke Ching, who finally fights back in a contest witnessed by no one and certain to result in the two masters’ mutual destruction.

The final freeze frame is weighted with so much futility and melancholy that audiences may well have left the theatre depressed rather than entertained. Seen at this distance, the ending gives tragic weight to the story, while it’s clear that Ching’s direction of the action had a huge influence on the future of the genre … not least on Tsui Hark, who hired Ching to direct the Swordsman trilogy in the early ’90s, and filled his own subsequent martial arts movies with similarly elaborate action sequences.

The 2K restoration on Eureka’s Blu-ray is eye-poppingly vivid, even if the source material displays some unevenness. Detail in some night scenes is not always clear, but much of the action takes place in bright daylight, and we can see every nuance of the choreography clearly. In the past couple of years, Eureka has released a lot of martial arts movies and the quality has been exemplary; Ching Siu-tung’s Duel to the Death is one of the best yet.

Comments