Early winter viewing, part 2

Code Red

Code Red is similar to Severin and other companies that specialize in exploitation and genre movies. In fact, over the years, as rights expire, some titles turn up in multiple editions, with one company occasionally duplicating the content of another as they license one another’s extras. If I have fewer of their releases, it may be because they seem to have a lower profile, distributing through a number of on-line retailers rather than from their own site (they can be found at Diabolik DVD, Ronin Flix, Screen Archives). At least two of their releases are prized additions to my collection – Robert Faenza’s Copkiller (1983) and Umberto Lenzi’s Almost Human (1974). One of these most recent acquisitions came from Ronin Flix, the other two from Unobstructed View.

The Curious Female (Paul Rapp, 1969)

This is an oddity about which I previously knew nothing. I hadn’t heard of Paul Rapp before coming across the listing at Ronin Flix. It turns out he had a fairly long career as a second unit director, production manager and producer, with quite a few credits on Roger Corman projects. The Curious Female (1969) was his only theatrical feature as director (and writer-producer) and to be honest, it’s a little difficult to figure out what he was aiming for. A strange mix of sci-fi social commentary and soft-core sex, it’s framed with a group of young people hundreds of years in the future who gather in secret to watch a movie from the 20th Century which exposes our weird social and sexual mores. This stuff is forbidden by the current totalitarian state which has essentially stripped sex of all its messy personal connotations.

In the movie they watch, virginity and losing it plays a big role, while in their own time it’s something to be disposed of quickly, without any emotional or moral complications (at a certain age, girls are sent to older men who do the task). But while ’60s hang-ups are mocked, the future with its supposedly enlightened attitudes seems pretty grim. It’s as if, without making an explicit point, Rapp recognizes that the hang-ups are what make sex an enjoyable activity. More an intriguing artifact than a satisfying movie, The Curious Female is very much of its time, something which perhaps could only have been made at that transitional point when the studios were in decline and the hold of the Production Code on movie morality had been broken.

Devil’s Express (Barry Rosen, 1976)

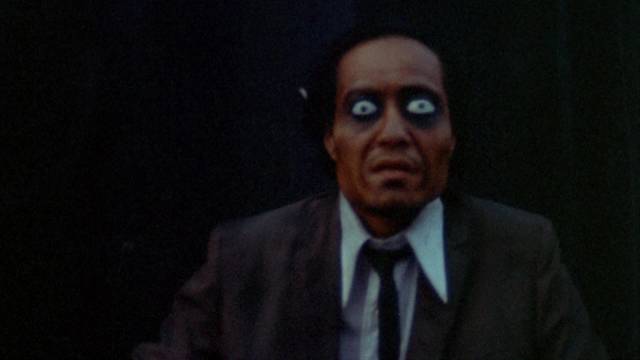

Barry Rosen’s Devil’s Express (1976) is the kind of genre hybrid which probably could only have been made in the ’70s. It begins with a period prologue in China in “200 B.C.” as some monks bury something deep in a cave and pin it down with a cursed relic. Jump ahead a couple of thousand years and a Black martial arts teacher (Warhawk Tanzania!) and his undisciplined student (Wilfredo Roldan) head East for some spiritual rejuvenation. The latter unfortunately steals the ancient artifact, inadvertently releasing a demon which follows the pair back to New York. When the demon possesses a Chinese businessman and starts killing people, it triggers a turf war between Black and Asian gangs, meanwhile preying on unsuspecting subway riders.

Powered by a pulsing soundtrack, the mix of eye-searing fashions, big hair, supernatural horror, martial arts, blaxploitation and gang turf wars makes for an entertaining exploitation stew, and Tanzania is visually arresting as the hero, although like everyone else involved is sorely lacking in acting talent. Best viewed as a party movie, Devil’s Express is not as good as it sounds, probably due to Rosen’s rather flat direction – he only had one other directing credit, a sex comedy made the same year, before embarking on a career as a television producer.

The Strangeness (David Michael Hillman, 1980)

Despite the on-screen directing credit, The Strangeness (1980) was directed by Melanie Anne Phillips, who made the movie for peanuts with friends from her UCLA film school days. Shot on 16mm, it’s actually quite daring visually, with almost all the action taking place in a disused gold mine with a bad reputation; particularly in the second half, much of it is shot with minimal practical light sources (helmet lamps and emergency flares). I can imagine how unwatchable it would have been on its original VHS release, which no doubt explains its relative obscurity. On Blu-ray, there’s actually a decent amount of detail visible.

A team is sent in to explore the mine to see whether it’s worth reopening, and tensions appear early. The place had been shut down because of too many fatal accidents and as the team goes deeper, it becomes apparent that these “accidents” were anything but – yep, there’s a monster down there, a squirmy, tentacled critter with a nod towards H.P. Lovecraft. If the film has a scrappy, threadbare, make-do quality, it nonetheless satisfies my craving for fringe regional movie-making. It may not have the unhinged weirdness of a Winterbeast, but it has its own charms.

Butcher, Baker, Nightmare Maker (William Asher, 1982)

Speaking of weirdness, I didn’t know what to expect from William Asher’s Butcher, Baker, Nightmare Maker (1982), a rare theatrical feature from someone best known for his work on TV sit-coms – I recognized his name from the 131 episodes of Bewitched he directed from 1964 to 1972. A belated entry into the so-called “hag horror” genre launched by Robert Aldrich with Whatever Happened to Baby Jane? in 1962, it stars Oscar-nominee Susan Tyrrell in a performance which begins as uncomfortable and steadily grows more unhinged as the movie builds towards a queasy, violent climax.

Tyrrell plays Cheryl Roberts, a woman who takes responsibility for her baby nephew Billy when his parents die in a freak car accident (we get to see his father’s head taken off by a large pipe which crashes through the windshield). Billy grows up smothered by Cheryl’s clingy over-protective care, but as he approaches the end of his final year at high school he’s planning to move away to college on a full scholarship. Cheryl is not happy about this and quickly plunges off the deep end. Her deranged plans to hold onto him begin with claiming that a repairman tried to rape her, forcing her to stab him to death with a kitchen knife. Investigating officer Detective Joe Carlson (Bo Svenson) suspects that it was really Billy (Jimmy McNichol) who killed the man, setting off a chain of events which trap Billy.

It turns out that the dead man was the gay lover of Billy’s high school basketball coach, who has been responsible for that scholarship. Raging homophobe Carlson sees a plot in this – the coach and Billy must be sexually involved, which caused Billy to eliminate his rival. Because of this blind spot, Carlson fails to see how dangerous Cheryl is as the bodies begin to pile up. It all gets messier and messier, complicated even more by a late revelation about Cheryl which makes her desire to hold onto Billy even more unsettling. A final flurry of violent twists leaves the stage littered with bodies and the surviving characters plunged into madness. The excesses build absurdly until, like Baby Jane, it teeters on the edge of black comedy. Although McNichol is a bit dull as the teen protagonist, Tyrrell and Svenson play their parts to the hilt, making the melodrama really entertaining.

*

Scorpion Releasing

Scorpion Releasing is another company specializing in genre and exploitation movies, but as it doesn’t have its own dedicated e-tail website, acquisitions are more scattered, a matter of random titles found elsewhere (again, Diabolik DVD, Screen Archives Entertainment, Ronin Flix). My latest buys were from a sale on the latter, including three Dario Argento movies which I’ll get around to eventually along with another Argento movie released by Vinegar Syndrome.

Terror Train (Roger Spottiswoode, 1979)

Roger Spottiswoode had a brief career as an editor in the early to mid-’70s, making an auspicious debut as one of the cutters on Sam Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs (1971), followed by the troubled Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid (1973), before solo work on Karel Reisz’s The Gambler and Walter Hill’s Hard Times (1975). After a break of a few years, he made his own directing debut with Terror Train (1980), just one of the flood of post-Halloween slashers made in Canada to take advantage of the tax shelter rules which supported production through the ’70s and ’80s. Horror was the genre of choice for investors looking to bury assets in this handy vehicle for avoiding business taxes.

Set on a vintage steam train and starring both Ben Johnson and Jamie Lee Curtis, Terror Train bridges the divide between classical Hollywood style (learned through Spottiswoode’s association with Peckinpah) and the new forms of violent exploitation aimed at teens. The story is standard slasher fare – a prologue in which a fraternity prank goes very wrong, followed by a series of killings years later in which the victims are the original stupid pranksters. The setting on an old steam train rented by the fraternity for a graduation party (with Johnson as the concerned conductor) gives it some atmosphere (I have a real soft spot for train movies) and there are some nice twists before we get to the resolution.

In addition to Curtis as the final girl haunted by her part in that original prank, there’s a smarmy villain played to the hilt by Hart Bochner and a young David Copperfield as the party’s main entertainment, his illusions mixing with the killer’s tricks to help divert the audience’s attention until the climactic reveal. One of the better tax shelter movies, Terror Train feels a bit old-fashioned compared to some of the harsher, more graphic slashers which came along over the next few years.

Robot Holocaust (Tim Kincaid, 1987)

There’s not much to say about Robot Holocaust (1987), a very threadbare post-apocalyptic adventure executive-produced by Charles Band. Writer-director Tim Kincaid made a number of movies for Band while taking a break from a long career in gay porn (Robot Holocaust was bracketed by Breeders and Mutant Hunt); this is the only one I’ve seen, and it has that distinctive ambience found in movies made by porno directors aiming for the mainstream. There’s a kind of gravitational pull which seems to be leading towards graphic sex which never actually materializes, leaving only the parodic genre elements seemingly intended to justify and support the missing sex.

Earth has been devastated, a malevolent dictator oppresses the population which struggles to survive, and a hero leads a ragged band to the bad guy’s headquarters to throw off his tyrannical rule. They face killer robots, mutant creatures and violent tribes who lay claim to the territory they have to cross. Nothing original here, and yet it has its charms – the blatant C3PO rip-off, the flesh-eating worms which are actually just hand-puppet gloves poking through holes in the set walls, and most of all the heavily-accented and endearingly talent-challenged Angelika Jager as the dark overlord’s enthusiastic henchwoman. Made for peanuts, the movie makes effective use of locations in derelict areas of New York and the disk’s image quality is surprisingly good.

*

Kino Lorber

I’m really backed up with my Kino Lorber purchases, but have managed to get around to a few.

She (Avi Nesher, 1984)

Despite the credits, Avi Nesher’s She (1984) has nothing to do with H. Rider Haggard’s Victorian adventure novel of the same name. In yet another of those post-apocalyptic worlds dominated by violent tribal societies, a couple of brothers and their sister are separated during an attack on a village. The guys are taken to the city ruled by She, who consumes men like snacks, while the sister is dragged off to a rival city. When the brothers manage to escape, they’re unexpectedly joined by She on their rescue mission, running into various different tribes (including a New Agey community who turn out to be werewolves) on the way to a climactic battle with the bad guys.

Often playing like a parody of the genre, She is mildly entertaining, notable mostly for the presence of Sandahl Bergman in the title role. A physically striking dancer who had made an impression in Bob Fosse’s All That Jazz (1979) and Robert Greenwald’s Xanadu (1980), she made a left turn into an action-fantasy career when she co-starred with Arnold Schwartzenegger in John Milius’s Conan the Barbarian (1982). She was definitely a step down from that, but she managed to bounce back the next year with a supporting role in Richard Fleischer’s Red Sonja (1985), with Schwarzenegger again.

I Bought a Vampire Motorcycle (Dirk Campbell, 1990)

I wanted to like this more than I ended up doing. As a fan of Don Sharp’s Psychomania (1973), I was hoping for an absurd concept played more or less straight, but writers Mycal Miller and John Wolskel and director Dirk Campbell know the idea is ridiculous and want to make sure the audience knows that they know – so they aim for a mix of comedy and horror and fall into the unsatisfying gully between the two. When a biker gang interrupts a Satanic ceremony and kill the cult leader, his spirit transfers to a bike which is then bought by a courier who gradually comes to realize that his new wheels run on blood. The humour is often tasteless (a famous talking turd which leaps out of the bowl into the hero’s mouth, for instance) and the horror pretty formulaic – the bike is out for revenge and kills off the gang members one by one. It all seems strained and disappointing.

Dead Men Don’t Wear Plaid (Carl Reiner, 1982)

Carl Reiner and Steve Martin teamed up for a brief run of commercially successful comedies in the early ’80s. Martin seemed to be channelling his inner Jerry Lewis back then and I confess I wasn’t a fan – I found The Jerk (1979) pretty tedious and didn’t bother with the two movies that followed, but actually found their final collaboration, All of Me (1984), quite entertaining. And yet it’s taken me forty years to get around to seeing the second movie they made together.

Pastiche is a tricky thing to sustain for a full-length feature and Dead Men Don’t Wear Plaid (1982) is pretty hit-and-miss. The idea of building a detective noir around clips from numerous old movies seems hubristic, but the script by Reiner, Martin and George Gipe hits the mark quite frequently. Martin is a hard-boiled private eye hired by a sultry woman to look into the murder of her father, a task which ultimately leads to a Nazi plot to destroy America. The gimmick is that much of the investigation involves inserting Martin into scenes from old movies where he meets (or at least talks over the phone with) people like Humphrey Bogart, Alan Ladd, Ray Milland, Barbara Stanwyck, Burt Lancaster, Ava Gardner, Ingrid Bergman, Cary Grant… Some of these interpolations are very funny, some rather perfunctory, and more than a few are visually jarring because the new footage with Martin is shot in crisp black-and-white by Michael Chapman which is a glaring mismatch with the old, grainy clips. Although I’m generally against messing with old films, this one would benefit from replacing the archival clips with new hi-def transfers – but back when it was made, they really should have degraded the new footage, adding some grain and maybe a few scratches to make it match a bit better.

But in addition to this technical issue, there’s one really problematic thing – a misogynistic streak which is supposed to be funny but instead leaves a sour taste. Rachel Ward’s heroine is drooled over and pawed by Martin in ways which make you embarrassed for the actress more than for the character who’s being abused. Even in 1982, this would have been off-putting, but today it’s blatantly unacceptable and makes Martin seem like a creep.

Filmworker (Tony Zierra, 2017)

It’s taken me four years to get around to seeing Tony Zierra’s documentary about Leon Vitalli, who appeared to be destined for a successful acting career when he gave it all up to become Stanley Kubrick’s assistant, a role which consumed his life for two-and-a-half decades until Kubrick’s death, and in a way has continued beyond that as he has become the de facto guardian of Kubrick’s legacy. I had heard and read interesting things about Filmworker (2017), but something made me hesitant. I’m not exactly sure what that something was, but having finally watched it I still feel ambivalent.

Vitalli had landed the role of Lord Bullingdon in Barry Lyndon (1975), having established himself as a successful actor on stage and television. The notoriously demanding Kubrick liked what he saw and expanded the role to give Vitalli more to do. For his part, Vitalli was fascinated by the way Kubrick worked and became increasingly interested in the filmmaking process. Over the next few years, he immersed himself in learning various aspects of film production and then offered his services to Kubrick. Beginning with The Shining (1980), Vitalli became the director’s all-purpose assistant, his first job being to find the young actor to play Danny Torrance. From then on, he worked tirelessly behind the scenes, casting, scheduling, dealing with labs, overseeing all the organizational details which would have distracted Kubrick from the creative work of directing.

What comes across in Zierra’s documentary is Vitalli’s complete immersion in this role; it seems that he gave up his own independent existence to become an extension of Kubrick, one which Kubrick himself came to take for granted. And yet we see glimpses of something else; among those interviewed by Zierra are Vitalli’s now-adult children, but we get little sense of what their lives were in light of their father’s complete devotion to Kubrick. In fact, we get no sense at all of a family life beyond his role as, as he terms it, “filmworker”. What we see is a man now approaching seventy who completely subsumed his own identity under that of the famous filmmaker, a man who for decades completely served another’s purpose.

Although Vitalli comes across as self-effacingly humble, still devoted to Kubrick’s legacy, with no apparent regrets, the documentary left me with an overwhelming sense of sadness. His identification with Kubrick’s films and the part(s) he played in their making seems like something he must hold onto by necessity, a justification for a monumental and irreversible decision he made about what to do with his life. Perhaps this is all projection on my part (I’ve never made any commitment on that scale); perhaps the feeling I came away with that there was unspoken damage done by this complete subjugation to another personality is just something I conjured up to fill a strange psychological absence at the heart of Zierra’s film. Even weeks after watching it, the thought of Filmworker fills me with a deep melancholy.

Comments