Folk horror and Argentine noir

in Román Viñoly Barreto’s The Beast Must Die (1952)

The year is definitely getting off to a good start. On the heels of the Joseph Kuo box set, I’ve seen a pair of beautifully restored films noirs from Argentina, an ambitious psychological horror from England, and an epic documentary exploring one of my favourite genres.

Argentine noir

My experience of South American cinema remains quite spotty, with the impression of radical political movies from Brazil in the ’60s and ’70s dominant, while Mexico is familiar from horror and fantasy films from the ’30s through ’60s. I had little idea that Argentina had a vibrant industry in mid-Century, so two noir features from the early ’50s, restored by the Film Noir Foundation and released in dual-format editions by Flicker Alley, come as something of a revelation. Both movies are atmospheric, with a pronounced melodramatic streak which contrasts somewhat with the cooler fatalism of much of American noir. Although the American influence is clear, there’s also an echo of the French poetic realism of the ’30s, with both styles amplified by Latin heat.

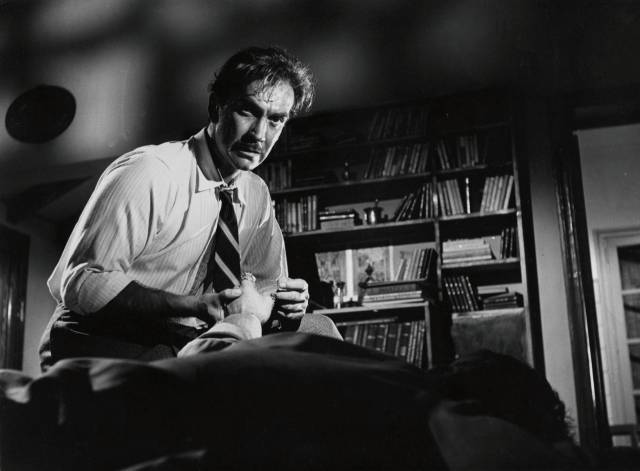

The Beast Must Die (Román Viñoly Barreto, 1952)

The Beast Must Die (1952) was adapted from the 1938 novel by British poet Cecil Day Lewis, written under his Nicholas Blake pseudonym (when poetry turned out to provide an insufficient income, Lewis took to writing mysteries under that name in the 1930s). Co-scripted by director Román Viñoly Barreto and star Narciso Ibáñez Menta, the film restructures the book’s narrative and reduces the role of Blake’s detective protagonist. In style, in addition to the previously mentioned influences, The Beast Must Die recalls the Gothic atmosphere of early ’30s Hollywood horror movies – not inappropriately, as there’s a genuine human monster at the centre of the story.

The film opens as Jorge Rattery (Guillermo Battaglia) arrives at his large country house. Preparing to eat lunch are his wife, stepson and sister-in-law, all of whom live in fear of his overbearing personality which seems ready to erupt in violence at the slightest provocation. As the family begin to eat, Rattery starts to gasp and quickly dies, his stomach medicine having been poisoned. Pretty much everyone in the house has a reason for committing the crime, and we are quickly given a strong hint about who is actually responsible. However, when the police arrive, their suspicions immediately settle on someone who wasn’t present – mystery writer Felix Lane (Menta), whom Rattery had just been to see to forbid him to have anything more to-do with his sister-in-law, actress Linda Lawson (Laura Hidalgo).

Lane’s journal, which has fallen into the hands of the police, describes in detail his plans to kill Rattery – plans made before he even knew the dead man’s identity. Here, the film goes into an extended flashback. Lane, a widower whose real name is Frank Carter, lives with his young son Martie (Eduardo Moyano). One foggy evening, Martie is killed by a hit-and-run driver, his body found by the distraught father beside the road in a sequence of full-on horror evoked with an Expressionist use of camera angles and extremes of muted light and pitch black shadows. Carter, once recovered from the shock, determines to find the person responsible and kill him or her.

Months pass before a crucial clue leads him to famous actress Lawson, who was apparently a passenger in the car which ran Martie down. Under his identity as mystery writer Lane, Carter insinuates his way into Linda’s life, piecing together the details of what had happened – she had been in the car with Rattery, who was trying to force himself on her sexually when he hit the boy in the fog. She’s tormented by guilt, but remains fearful of Rattery.

Carter, as Lane, not only becomes close to Linda; he also befriends Rattery’s stepson Ronnie (Humberto Balerdo), becoming something of a substitute father. Through Linda and Ronnie, Lane learns just how monstrous Rattery is, an arrogant, conscience-less brute who possesses no remorse for having killed a child. While Rattery has reason to despise Lane for his rapport with Linda and Ronnie, it’s the discovery of the journal which gives him a weapon to drive Lane away. As Lane prepares to kill Rattery by pushing off a sailboat far from shore, the ogre reveals that he knows of the plan and that the journal is now with his lawyer, to be given to the police is anything happens to him. It is on his return from this confrontation that he is poisoned.

The mystery of who committed the murder is not really the point – the attentive viewer will figure it out quickly from a single exchange of glances immediately after the death. What matters is the toxic effect a single odious man has on everyone who comes into contact with him. The traumatic death of Martie is the most obvious manifestation, but Rattery is relentlessly destroying everyone in his household psychologically and spiritually with his malevolent compulsion to control and manipulate.

The Bitter Stems (Fernando Ayala, 1956)

Fernando Ayala’s The Bitter Stems (1956) eschews mystery for a noir-steeped character study about a man whose inherent weaknesses lead him to commit a terrible act for which he is then plagued by guilt which escalates to self-destructive madness. The protagonist is Alfredo Gaspar (Carlos Cores), a reporter who has grown cynical and resentful of the seeming career dead end he has reached at a newspaper. When he meets a cheerful conman at a bar, he agrees to go into business with him. Liudas (Vassili Lambrinos) is a refugee from war-torn Europe who is looking for a quick way to raise money to bring his family to safety in Argentina. His plan is to start a correspondence school to pry money from gullible people who want to become journalists. He has the organizing ability, while Gaspar has the know-how.

The plan is a huge success, though Gaspar knows that he’s traded his unsatisfying newspaper career for a morally dubious alternative. As Liudas talks endlessly of his family, particularly of his favourite son Jarvis, Gaspar lets the other man pocket the majority of what they’re earning, to speed up the reunion. But doubts begin to nag at him – after all, Liudas is cheerfully open about his conman tendencies. The crucial turning point comes when Gaspar follows his partner to a nightclub and sees that the supposedly devoted family man is involved with another woman. Seating himself nearby, Gaspar tries to listen into their conversation, but he only catches broken fragments over the sound of the loud jazz band. Those fragments suggest that Liudas is taking advantage of Gaspar and laughing at his gullibility for believing the story about his family.

And so Gaspar decides to kill Liudas and keep all the money for himself. Having concocted a story that Liudas has gone on a tour of a neighbouring country to drum up more business for the school, Gaspar carries on … until one day Jarvis (Pablo Moret) shows up, a charming young man looking for the father who sent him the money to get to Argentina. Gaspar is abruptly confronted with the undeniable fact that he has committed a horrific murder based on a mistaken impression (we later see a replay of that conversation in the nightclub from the woman’s point of view with Liudas expressing warmth and gratitude towards Gaspar for his generosity – a reversal which plays like a forerunner of the shifting interpretations of the recorded encounter in Francis Ford Coppola’s The Conversation [1974]).

The realization that what he did was unjustified is aggravated by the trust in him shown by Jarvis, who becomes romantically involved with Gaspar’s younger sister Esther (Gilda Lousek). Gaspar’s guilt, his descent into self-inflicted madness, leads him to other misunderstandings, the final one – a moment of optimism for the future – pushing him to his own self-destruction.

In keeping so close to Gaspar’s own perceptions, the film has a claustrophobic atmosphere, it’s noirish expressionism a reflection of the character’s distorted view of the world. This tendency towards misunderstandings and negative interpretations of innocent events is present from the start, Gaspar’s unhappiness in his work feeding a nascent idea that somehow everyone and everything is against him. In striking out against those supposedly oppositional forces he inevitably brings about the thing he had feared.

Both films look terrific on Flicker Alley’s Blu-rays, with sharp detail and rich contrast bringing out the expressive qualities of the cinematography. Each film gets an introduction from Film Noir Foundation’s Eddie Muller and featurettes with Argentine cinema archivist Fernando Martin Peña. The Bitter Stems disk also has a featurette on score composer Astor Piazzolla, and each film has a commentary track and booklet with an essay and promotional materials.

*

Censor (Prana Bailey-Bond, 2021)

Prana Bailey-Bond’s Censor (2021) is a remarkably assured first feature which tackles its subject – the complex relationship between movies and those who watch them – along multiple axes. The narrative itself is complex, but the self-reflexive stylistic play adds critical and psychological layers which transform this horror film into a textual analysis of the ways in which cinematic horror affects the audience. And it accomplishes this without ever slipping into academic arguments, always functioning on the level of a popular narrative form.

Bailey-Bond and co-writer Anthony Fletcher situate the story in the midst of the British “video nasty” furore of the 1980s, with central character Enid Baines (Niamh Algar) working as a censor for the British Board of Film Classification (shortly after it changed its name from the British Board of Film Censors). She spends her days watching an endless stream of videos submitted by hopeful distributors, a flood of graphic sex and violence which she and her co-workers must judge with regard to their fitness for public consumption – either to be passed with cuts or banned outright. This was a time when conservative forces in the Thatcher government and in society at large (most prominently embodied by the middle class Mary Whitehouse) were casting about for explanations of why society was going to Hell. Nothing to do, of course, with political repression, extreme economic inequality, the crushing of organized labour – it was all the result of rising tides of immorality, of which disgusting movies finding their way into the sacred confines of the family home were emblematic.

Early in the film, the press and politicians latch onto a brutal murder which bears a passing resemblance to something in a video Enid and another censor had passed for viewing. As in the cases of Michael Ryan, who went on a shooting rampage in Hungerford in 1987, and the murder of two-year-old James Bulger by two ten-year-old boys in 1993, the connection to a violent video (Rambo in the first case, Child’s Play 3 in the second) is only anecdotal, but the tenor of the times ensures that those in authority can claim a certain, irrefutable connection. This puts additional pressure on the censors as they try to parse the limits of acceptable cinematic offence.

We get a sense early on that there is another dimension to Enid’s meticulous examination of the scenes of violence she is watching – she goes frame by frame through a murky scene of a woman being attacked in woods and dragged away from the camera. When her co-worker notes that this really isn’t necessary, she says that she’s trying to see who is dragging the woman away. A bit later, we learn that when she was a child her younger sister disappeared and that she may have witnessed what happened, though she has no memory. On a barely subconscious level, she is searching these movies for clues about what had happened to her sister.

Then she’s confronted with a movie which seems to recreate that childhood experience, implicating her as an active participant in whatever happened to her sister. This draws her into an investigation which goes far beyond the bounds of her job – leading to the film’s sleazy producer, Doug Smart (Michael Smiley), and pretentious director, Frederick North (Adrian Schiller), as she tries to track down the actress Alice Lee (Sophia La Porta), whom she becomes convinced is her missing sister. She also becomes convinced that her “sister” is once again in danger, this time from the exploitative filmmakers who have nefarious plans for her.

Enid’s memories, her sense of guilt, the nature of her work – all combine to distort her perception of reality, leading her on a slippery slope into madness which triggers acts of violence which in turn reiterate the graphic content of the movies she watches all day, every day at work. Enid’s descent is embodied in various stylistic elements which display the decay and fragmentation of the mechanisms of cinema itself. Shot on 35mm film, which gives Censor a rich visual palette, the image is increasingly disrupted with intrusions of 8mm and VHS which push it away from an objective treatment of narrative towards an unreliable subjectivity, which in turn adds plausibility to the climactic explosion of violence.

Censor is a polished and intelligent meditation on horror cinema, and a perceptive psychological character study – it can sit comfortably on the shelf beside Peter Strickland’s Berberian Sound Studio (2012) – but it also displays the conservatism inherent in horror as a genre. Ironically, its intricate narrative supports the outrage expressed during the video nasty moral panic: the trajectory of the film shows step by step how the interaction between individual pathology and violent screen imagery leads inexorably, and inevitably, to real acts of violence. One of the arguments against the ’80s moral panic was that a daily diet of these violent movies didn’t corrupt the censors, so there was always an implicit class bias, an unspoken assertion that the less educated masses had no defences against the corrupting influence that their betters were immune to. In Censor, the narrative undermines that prejudice, not by asserting that everyone is capable of discerning the difference between fantasy and reality, but by illustrating that the educated middle class (in the person of Enid) is as susceptible to corruption as the unwashed masses.

Vinegar Syndrome’s Blu-ray provides a gorgeous transfer and a plethora of extras – two commentary tracks and multiple interview featurettes, as well as Bailey-Bond’s short film Nasty (2015), which laid some of the thematic groundwork for the feature. In addition, the disk includes David Gregory’s documentary about the video nasty panic, Ban the Sadist Videos (2005-06), plus a lengthy chat with Gregory about his personal experiences as a horror movie fan living through that period.

*

Woodlands Dark and Days Bewitched (2021)

Woodlands Dark and Days Bewitched:

A History of Folk Horror (Kier-la Janisse, 2021)

I first heard about Kier-la Janisse’s documentary about folk horror almost a year ago and have been eager to see it since those initial tantalizing hints about the project. I got to know Kier-la a little when she joined the staff of the Winnipeg Film Group’s Cinematheque for a while as a programmer. She already had extensive experience at the time from her work in various theatres and festivals (subsequently going on to create the Miskatonic Institute of Horror Studies and small press publisher Spectacular Optical) and found Winnipeg to be frustrating, with local audiences unresponsive to her programming. After she moved on, FAB Press published her remarkable book of autobiographical film criticism, House of Pychotic Women, and later a volume of essays about the Satanic Panic of the ’80s and ’90s which she co-edited. Eventually she joined the staff of Severin Films as a producer of disk extras and occasional presence on commentary tracks.

And then came her epic documentary, which had begun as a proposed featurette for Severin’s release of Piers Haggard’s The Blood on Satan’s Claw (1971), but eventually grew to encompass a global survey of a genre (or mode) which is almost as slippery to define as film noir. In broad terms, folk horror occurs at the intersection of the ancient and the modern where Christianity clashes with paganism, a conceptual landscape permeated with forces which resist and disrupt modern society.

The idea of this particular genre was sparked by three particular British features made in a brief period as the ’60s bled into the ’70s – Michael Reeves’ The Witchfinder General, Haggard’s Blood on Satan’s Claw and Robin Hardy’s The Wicker Man (1973) – but its roots go back further and encompass works like Benjamin Christensen’s Haxan (1922), Carl Dreyer’s Vredens Dag (Day of Wrath, 1943) and Erik Blomberg’s The White Reindeer (1952). These movies draw deeply from folk and fairy tales and often add layers of social and political critique to their stories of demons and monsters impinging on human society.

Woodlands Dark and Days Bewitched begins with that seminal British trio, but casts an increasingly wider net which shows how the underlying themes of the genre can be found in other places and other cultures – eastern Europe is fertile ground, but so are Australia and Brazil – and the farther the film travels, the richer its thematic analysis becomes, drawing in issues of gender, of imperialism and colonialism. As much as the conflicts are between modern and ancient, between Christianity and paganism, they are also between male and female, between European and indigenous cultures.

Gender is unavoidable because of the almost universal sexual element which runs through so many of these movies – the pathological hatred of the inquisitors for women who express any kind of independent sexual identity, the feminization of “primitive cultures” by “rational” conquerors, the association of the female with nature and animals while men are linked to politics and the law, forms of oppressive order determined to subdue unruly elements which threaten to undermine their power.

While the documentary references a huge number of movies, it doesn’t critique or analyze them individually. It’s not a catalogue so much as an impressionistic collage which uses multiple sources to embody its themes. At times this can be frustrating as we get glimpses of individual works we might want to linger on, to learn more about them, but the strategy pays off in the end in a dense, richly layered portrait of the genre itself, beyond the individual details of the many works cited. This collage effect is embedded into the documentary stylistically, with transitional elements created by animator Ashley Thorpe (whose own genre-bending documentary Borley Rectory [2017] I wrote about a couple of years back) and Guy Maddin.

Woodlands Dark and Days Bewitched is a remarkable achievement, gathering a great many elements into a multi-layered yet coherent whole which inspires an urge to explore the folk horror genre in more depth. Severin has facilitated the beginnings of that exploration by boxing the documentary with nineteen features from around the world, plus short films, interviews, commentaries, three CDs and a one-hundred-and-twenty-page book of essays and notes on the individual films in their impressive All the Haunts Be Ours fifteen-disk set. I’ll be working on that for a while, resisting the temptation to binge it all.

Comments