The martial arts of Joseph Kuo

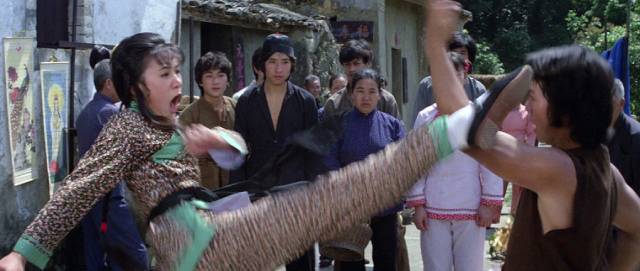

in Joseph Kuo’s Return of the 18 Bronzemen (1976)

The year has only just begun and I already feel way behind. I haven’t said much about what I was watching in December and now I have to move on to more recent titles. I’ve passed over all those Vinegar Syndrome Black Friday releases – New York Ninja, Creature, Ebola Syndrome, Tiger Claws 1-3, Don’t Answer the Phone, Graduation Day, Memorial Valley Massacre, Steel and Lace, TC 2000, The Severed Arm, Deadly Games: Dial Code Santa Claus; two AGFA triple bills, Blood-a-Rama and Satanic Horror Nite; plus a pile of other random titles: Eureka’s Sabata Trilogy, Indicator’s Grey Lady Down, Shameless’ The Case of the Bloody Iris, Zack Snyder’s Justice League, Robert Hartford-Davis’ blaxploitation double-bill of The Take and Black Gunn, Frank Henenlotter’s Frankenhooker, Mark Lester’s Class of 1984, Krampus, The Forever Purge, F9 The Fast Saga, Anthony Hickox’s Sundown: The Vampire in Retreat, Venom: Let There Be Carnage, Goro Miyazaki’s Earwig and the Witch, Nia DaCosta’s Candyman remake, Michael Sarnoski’s Pig, the horror anthology Deathcember, both seasons of Castle Rock, George Lautner’s Icy Breasts, Juraj Herz’s Ferat Vampire, and Justin Benson and Aaron Moorhead’s Synchronic.

There are some easy to ignore items in there, but also quite a few that deserve a comment, but today I’ll move on to what I started January with – a hefty box set from Eureka.

*

in Joseph Kuo’s The 7 Grandmasters (1977)

Cinematic Vengeance is a set of eight features on four disks, all directed by Joseph Kuo in the 1970s. I hadn’t seen any of his work before (I checked back over the large collection of martial arts movies a friend in New York sent me years ago, but there are none by Kuo), but judging by these – uneven though they are – he really should be better known. Working independently in Taiwan, on budgets just a fraction of what Shaw Brothers and Golden Harvest were spending on their movies in Hong Kong, Kuo’s films may not have had the technical polish of better-known productions, but he was obviously a master of the genre.

While mostly adhering to familiar genre tropes, Kuo managed to throw in some interesting curves which give some of these movies unexpected depth and occasional emotional power, while the fight sequences themselves are often spectacular – elaborately choreographed and shot and edited with precision. The performers almost all have remarkable physical skills and their work possesses a visceral impact which is guaranteed to make the viewer wince at times at what must have been genuinely painful.

The set covers several different styles, edging from unarmed combat into more traditional swordplay, with one movie (the one I liked least) set in contemporary Los Angeles. I’m not sure what organizing principle Eureka used – they’re not presented in chronological order – but all four movies in the second sub-set, Fearless Shaolin!, do reference the famous temple and its place in martial arts tradition, even if only tangentially. The first sub-set, Deadly Masters!, is much looser.

Typical of the genre (and obviously signalled by the set’s overall title), revenge is a common theme in many of the movies, with betrayals and murders requiring someone to master the arts of unarmed combat to punish those who have harmed them or their families. Notable in Kuo’s treatment of this theme is a darkness and melancholy which undermines any sense of triumph; vengeance is a burden which does emotional and spiritual damage to the avenger even as it physically punishes the transgressor. For films which were made for clearly commercial purposes, sometimes rushed and full of rough edges, there’s nonetheless a sense of authorial identity, a worldview which gives them a bit more depth than so many other martial arts movies which exist mostly as a frame for a string of action sequences.

in Joseph Kuo’s The 7 Grandmasters (1977)

In The 7 Grandmasters (1977), the sifu of a martial arts school is presented on the eve of retirement with an award from the emperor, recognizing him as the greatest master. But just before the ceremony, someone challenges his claim and, despite declining health, he delays his retirement and embarks on a long journey to challenge all the other masters to a friendly duel to prove his worthiness. Along the way, he and his entourage are annoyed by an insistent young man who wants to become his student. Despite efforts to discourage him, the young man’s persistence finally wins the master over and during the long journey he proves himself an excellent student. But after the final duel, he finally reveals that he is on a mission to get revenge on the master, whom he believes killed his father in the very first encounter of the journey. A flashback reveals the truth of what happens and when the real villain is exposed, the young man must redirect his vengeance and join forces with the master.

In The 36 Deadly Styles (1980), the audience is dropped into the middle of the action without orientation. As it opens, there’s an on-going fight and we have no idea who anyone is or what it’s about – the only clues are visual; one of the fighters has a pinched face and an inflamed red nose, hanging back as he directs others to attack, so we can safely assume that he’s a bad guy and the two he and his gang are fighting are the good guys. This proves a safe assumption, and we gradually learn that this is about a rivalry between two martial arts schools (the most common narrative trope in the genre). Unlike some of the films in the set, this one feels almost carelessly thrown together, the framework barely constructed as it rushes from one fight to the next, with awkward bits of comic relief tossed in. But the fights themselves are excellent, providing the requisite visceral and aesthetic satisfactions even if it lacks the psychological and thematic depth of the best films in the set.

The World of Drunken Master (1979) was obviously made to cash in on the recent success of Jackie Chan’s breakthrough movie, and it does repeat many elements of that hit, but even here Kuo finds an original angle. It opens with Beggar So (the drunken master) and another master, Tai Pei, receiving invitations to a mountaintop inn. When they arrive, they recognize each other as friends who haven’t seen each other for thirty years – and we go into a flashback which makes up most off the running time, with them meeting as young men both of whom have been raiding a vineyard, stealing valuable grapes and selling them in the local market. Caught, they are forced to work for the winery and eventually become students of a martial arts master who trains them in gruelling ways similar to those used by Beggar So in the Chan movie. The two both fall in love with the daughter of the winery owner and become embroiled in a fight with the bad guys who are trying to take over the business. In a surprisingly dark turn, their boss is killed and his daughter plunges off a cliff during the big fight – heartbroken, the two friends separate and go their own ways until brought to the rendezvous by those mysterious invitations. Although there’s a surprise twist, the ending remains melancholy and downbeat.

The final movie in the set’s first half is The Old Master (1979), cheekily titled to cash in on Jackie Chan’s The Young Master (1980), which it beat into theatres. The cheekiness went even further, as the movie stars Yu Jim-Yuen, who had been the teacher of Chan, Sammo Hung and Yuen Biao in the days of their Peking Opera apprenticeship. Because Yu had retired to Los Angeles by then and had no interest in returning to China, Kuo had to bring the production to him. And because any attempt at a period piece would have been prohibitively expensive, the story had to be set in the present day. So Yu plays a retired master who arrives in L.A. to help a former student whose martial arts school is in trouble. What he doesn’t realize at first is that his unscrupulous student is using him, betting on a series of fights against the school’s rivals. Disgusted, the master settles in with a young fighter and just hangs out, the movie becoming a fish-out-of-water story burdened with a lot of very strained “comedy” (fat women are funny because, you know, they’re fat but still interested in romance and sex). Although there are some good fights, the pacing is surprisingly clumsy (the scene at a disco seems interminable). It was a relief to get back to Taiwan and the genre’s past in the rest of the set.

Shaolin Kung Fu (1974), the earliest movie in the set, has a really generic title which actually doesn’t reflect the content; there’s no apparent connection with the famous temple. What it does have is an interesting narrative trigger which involves not rival martial arts schools, but rival rickshaw companies. One is run by a timid boss unwilling to stand up for the rights of his employees, the other by a gangster whose men use violence to intimidate the competition. Our hero works for the former, held back from defending himself and his co-workers by the exhortations of his blind wife never to fight again.[1] Needless to say, the situation gets increasingly bad and fight he must, but even standing up for himself turns out to have catastrophic consequences. The movie becomes extremely dark as it progresses, the fights escalating in brutality.

The next film, The Shaolin Kids (1977) is more wuxia pian than kung fu, and that means that the focus shifts from ordinary folks to the ruling class. Although the budget was probably no higher than usual, Kuo adds a sense of scale and opulence, particularly in the emperor’s throne room where richly dressed courtiers attend to their ruler’s demands. Typical of wuxia, women take on a bigger role – also typical, the heroine dresses as a man and is accepted by the other characters as male although the audience simply has to accept this genre trope despite the character obviously being female. Also typical of wuxia, the plot hinges on a dangerous document which various factions fight to take possession of – one such fight inevitably taking place in a two-level tearoom. Kuo is not breaking any new ground here – in fact, the movie seems old fashioned at a time when kung fu dominated the action market – but he displays his usual skill with the fight scenes and adds a touch of elegance with the royal court and its denizens.

Kuo finally gets to the Shaolin Temple in the final two movies in the set, which focus on the harsh and rigorous training the temple was famous for, with acolytes tested spiritually as well as physically. The Bronzemen of the titles constitute a final test before “graduation”, a particularly stringent one which few seem to pass (others appear to be killed during the ordeal, which seems a tad counterproductive after the years of effort invested in training).

In 18 Bronzemen (1976), revenge is a very long game, with those caught up in it trapped by obligations they barely comprehend and are not emotionally invested in. In the opening sequence, internecine fighting among court officials leads to the massacre of a family, with only a baby boy saved by a faithful retainer. This boy is eventually placed in Shaolin Temple and raised to be a skilled fighter. Two other students grow up alongside him, one very supportive, the other constantly challenging him. When they reach the end of their training, all three must pass through the maze where the Bronzemen try to stop them. Initially, these seem almost like robots from an old sci-fi serial – mechanical figures of golden metal – but then others seem to be men in full body paint. Their nature is never really explained; they are just a deadly physical challenge to be overcome on the way to self-realization. It’s only after the three friends have made it through the maze and emerged as certified Shaolin fighters that we learn their full identities and how their fates were laid down decades earlier; now they must act out a drama of revenge whose seeds were planted in that opening massacre. As in several of the films in the set, there’s no sense of triumph in the resolution, just a deep melancholy arising from the burdens imposed on characters who would rather have a different life.

Despite the title, Return of the 18 Bronzemen (1976) has no narrative connection to the previous movie. It tells an entirely separate story of another character’s experience at Shaolin Temple which culminates in that final deadly challenge – with new variations on the obstacles posed by the Bronzemen. The film opens in the royal court (Kuo making extra use of his expensive set and costumes) with an ambitious Prince disposing of his father and altering the will to make himself heir to the throne, then framing his brother for treason for good measure. He then proceeds to order the destruction of Shaolin Temple because its independence threatens royal power. From here, we see the Prince and his cronies coming across a market stall displaying replicas of the famous Bronzemen and he makes a decision to undergo the temple’s training. Arriving at Shaolin, he’s told he’s too old to start, but he persists until the Abbott relents and he pushes hard to achieve a level of skill which will enable him to face the Bronzemen. After several failed attempts over three years, he finally accomplishes the task – but at the last step the Abbott stops everything; he has learned this student’s true identity and realized that he has gone through the training in bad faith. He won’t be allowed to “graduate” and is forced to leave in disgrace… I was confused by the film’s narrative trajectory until John Oliver’s notes explained that everything from the beginning of the market scene is flashback. The Prince is not yet emperor when he heads for the temple and his viciousness and cruel ambition in the opening sequence is actually a consequence of his failure and humiliation at the very moment he believed he was proving his worth in the maze of the Bronzemen. Hence his order to send an army to destroy the temple as soon as he gains the throne.

As reported in Oliver’s notes, and confirmed by a cursory scan of some on-line reviews, Kuo hasn’t been held in very high repute by fans of the martial arts/kung fu genre. Perhaps I simply don’t have wide enough experience to judge, but despite their occasional ragged qualities (on my viewing, I completely missed the shift to flashback in Return of the 18 Bronzemen and spent the movie wondering who was running the nation while the new emperor was incognito in the temple), most of the movies in the set have characters with interesting personal quirks – they’re not just two-dimensional puppets used as narrative placeholders; the movies are often visually impressive, with an expressive use of moving camera; and the shooting and editing of the elaborately choreographed fights bring out the full impact of the physical abilities of the performers and the frequently brutal action.

As for those performers, like many lower-budget exploitation filmmakers, Kuo had a stock company of talented actors, many of whom are incredibly agile, able to use their bodies in ways that look almost physically impossible, like great gymnasts. Particularly impressive are Jack Long (in four of the films), Carter Wong (in three) and Polly Ling-Feng Shang-Kuan (also in three), who had made her debut in King Hu’s Dragon Inn (1967) and had become Taiwan’s biggest star.

In addition to mostly excellent transfers – it’s surprising how pristine many of the films look given their low-budget origins in a typically quite disposable genre – each movie gets a commentary from familiar names in this genre (Frank Djeng, Mike Leeder, Arne Venema, John Charles). The only other extra is a patched-together recreation of the original Hong Kong release version of 18 Bronzemen, which was radically re-edited for a Japanese release. That revised version is the one used for this set as the elements of the HK cut have been lost. Drawn from numerous sources of widely varying quality (including a pan-and-scanned VHS), the original version begins with the baby being delivered to the Temple, the attack on the family arriving very late in the narrative as a flashback triggered by the hero reading a letter written in his father’s blood, imposing the duty of revenge which is played out in the final act. There are other scene extensions and transitional details which flesh out and clarify a number of narrative points which are skipped over in the Japanese cut, indicating that Kuo was a more careful storyteller than the Japanese cut suggests.

This set was a great way to start the year … I wonder if my opinion will be tempered once I’ve worked through Arrow’s big Shawscope box set.

_______________________________________________________________

(1.) Eureka always put a lot of care and attention into their releases, but there’s a huge, inexplicable error in the accompanying booklet which contains essays on each of the films by the knowledgeable John Oliver. In his notes on Shaolin Kung Fu, he claims that it’s never explained how the wife became blind or why she’s so insistent that her husband not fight, nor indeed where and how he learned his formidable fighting skills; “it’s not impossible that she went blind as a consequence of his fighting.” He sees this as a big narrative gap, and yet there’s a lengthy flashback in which all of this is explained. How did Oliver manage to miss this key sequence? Our hero was a student at a martial arts school whose sifu was his wife-to-be’s father. One day, her father (not in the best of health) was challenged by a rival and during the fight, the father was killed by an underhanded trick which involved throwing a caustic powder into his eyes. His daughter, who was trying to stop the fight, was blinded by the powder, losing her father and her sight during a senseless fight, which turned her against the very idea of fighting, no matter what the circumstances. All extremely clear as an explanation for what occurs during the main storyline.

On the other hand, Oliver’s notes were helpful in clarifying a very confusing narrative point in the final film in the set, Return of the 18 Bronzemen (1976). (return)

Comments