Year End 2021

It’s that time of year again – time to look back over what I’ve been watching and figure out what was “the best”. Although being back at the office this year gave an illusion of greater normality than the disorienting first year of the pandemic, it’s still been a bit of a blur and part of my own coping mechanism seems to have been to immerse myself in an endless flow of trashy genre movies. Maybe it’s the crazy times, or maybe it would have happened anyway as I get older and lazier, but I frequently choose distraction over the challenge of serious cinema. While this tugs at my conscience (not least because I continue to accumulate a lot of great movies which remain unwatched), it often feels easier to give in and indulge in yet another slice of exploitation.

And yet, looking back over the year, I see that this isn’t strictly true. There have been quite a few more challenging movies, and a number of interesting discoveries both in unknown (to me) classics and more recent works which had not previously come across my radar. My less respectable tendencies have definitely been facilitated by the incredible quantity of high-quality releases devoted to lower-end cinema from dedicated companies like Arrow, Vinegar Syndrome and Severin. But there has also been the counteracting gravitational pull of other labels like Criterion and Indicator. Before the pandemic, I would get together more frequently with friends who’d want to watch something more serious, but the pandemic has made movie-viewing an almost exclusively solitary pastime for almost two years now. So maybe, if Covid does finally disappear, some kind of balance between art and exploitation will eventually be restored.

In the meantime, here are some of the more enjoyable and interesting releases I’ve indulged in this year.

*

Box Sets

It’s been quite a year for box sets, which brings back fond memories of the early days of DVD, with multiple movies given critical and historical context which enhances the value of individual titles and provides an opportunity to see movies which might not have come to my attention on their own. The majority of these sets came this year from Arrow, Indicator and Eureka.

Eureka

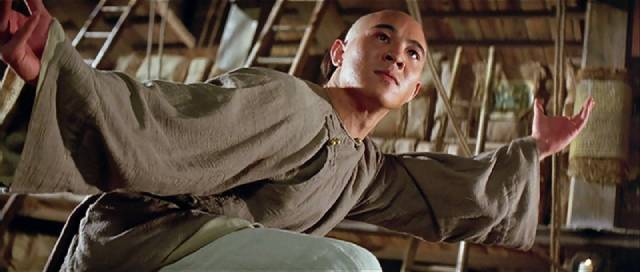

Once Upon a Time in China (1991-97): This four-disk set, showcasing Tsui Hark’s original martial arts trilogy plus Sammo Hung’s Once Upon a Time in China and America, all starring Jet Li as Wong Fei-hong, the Chinese national hero who repeatedly confronts the European colonial powers oppressing the Chinese in Shanghai, has already been eclipsed by Criterion’s recent release which includes two more non-Tsui-directed sequels along with some additional extras. But the Eureka set itself is excellent, and since the original three movies are the best, and most influential in redefining the genre, it remains a worthwhile purchase.

Inner Sanctum (1943-45)/Karloff at Columbia (1935-42): These two sets each gather six cheap, disposable studio B-movies (from Universal and Columbia respectively) which were just program filler when they were made, but have survived as fan favourites for eight decades or so thanks to atmospheric production values and the presence of genre stars Lon Chaney Jr and Boris Karloff. Creaky scripts and genre cliches are now part of their charm and for the most part the digital restorations reveal just how good at their jobs the technicians working at the studios back then were.

Cinematic Vengeance (1974-79): Just received and still unwatched, this set includes eight independent features from the first wave of martial arts, made in Taiwan rather than Hong Kong by Joseph Kuo, a filmmaker I’m unfamiliar with. This will take a real commitment in terms of time and attention, but I’m looking forward to getting to it soon.

Indicator

Hammer Vol. 6: Night Shadows (1961-64): Indicator has continued to release additions to a couple of on-going series, with this latest volume of Hammer movies once again collecting together a mixed bag of four titles with a lot of supplementary material. Enjoyable, though in this case the movies are perhaps further from Hammer’s more significant releases than some of the previous sets.

Columbia Noir 2, 3 & 4 (1947-59): Indicator ramped up production of their excellent series of film noir B-movies produced by Columbia between the mid-1940s and late ’50s. As with the Eureka sets mentioned above, these are a testament to the strengths of the studio system which employed skilled technicians and a roster of contract actors who could make impressive genre films on short schedules and tight budgets which hold up as entertainment more effectively than a lot of more prestigious productions from the same period.

John Ford at Columbia (1935-58): This is an older set, released in 2020, but new to me, a collection of four movies which exist on the fringes of the Ford pantheon. A mixed bag, which includes its fair share of what I find so grating in Ford, but also qualities which contribute to my perpetual personal reevaluation of his work.

Mae West (1932-43): Just acquired and not yet watched, this set includes all ten features in which West appeared before the long hiatus until her re-emergence in her seventies for Myra Breckinridge (1970) and Sextette (1977). Yet another viewing project which will require some concentrated time and attention!

Arrow

Arrow continue to excel with the range of material they cover and the quality of the transfers and extras in their releases. Three sets highlight individual filmmakers, while others focus on particular genres.

William Grefé/Bill Rebane: These two sets showcase a pair of regional filmmakers working far from the mainstream – Florida and Wisconsin respectively – on often absurdly low budgets with results which are occasionally ridiculous, but sometimes show levels of resourcefulness and imagination in a variety of genres. The Grefé set includes seven features (1966-77) and a documentary; the Rebane six features (1965-88) and a documentary.

Sam Sherman: Producer Sam Sherman worked closer to the mainstream, but on the fringes of the studio system, providing low-budget program filler which relied on writers and directors capable of turning out quick simulations of studio product. The four movies (1955-57) in this set (a welcome upgrade from an older Sony DVD set) piggy-backed on the flood of sci-fi and horror released by the studios in the ’50s.

Vengeance Trails (1966-70): The success of Sergio Leone’s Dollars trilogy (1964-66) unleashed vast numbers of Italian westerns over the rest of the decade, with pretty much every commercial director tackling the genre at least once. Arrow’s set brings together four features by filmmakers not primarily associated with the western who bring a range of styles, particularly horror, to the task.

Years of Lead (1973-77): Towards the end of the ’60s and into the ’70s, the western was superseded in Italy first by the giallo and then the poliziottescho, bringing together crime and psychopathology in a flood of blood-soaked thrillers. While the giallo focused on amateurs trying to solve murders, the poliziottescho generally dealt with cops, often modelled on Dirty Harry, resorting to unorthodox (and violent) methods to combat a rising tide of crime and terrorism plaguing Italian cities during that turbulent decade. This set gathers together five features which provide a survey of the genre’s range, from perverse sociopathy to adrenaline-rush action.

Yokai Monsters (1968-2005)/Daimajin (1966): Following their monumental Gamera box set, Arrow released a couple of more modest Japanese fantasy sets, each with their own particular charms rooted in the rich tradition of jidaigeki, the period films populated by samurai, gangsters, peasants and, in these cases, ghosts and supernatural monsters. Both sets display the considerable skills of Daiei’s studio craftspeople, who create a rich visual combination of sets, miniatures and optical effects.

Battle Royale (2000): I’ve lost track of the number of times I’ve bought new editions of Kenji Fukasaku’s final masterpiece since I first discovered it twenty-odd years ago, but Arrow’s big new set will probably stand as the definitive edition which will no longer need upgrading. It contains 4K restorations of both versions of Battle Royale and both versions of Kenta Fukasaku’s lesser sequel Battle Royale 2, plus a soundtrack CD, a book by Tom Mes, a collection of essays, and collector cards.

Shawscope 1 (1972-79): Just received but not yet viewed is this massive new set of twelve features produced by Hong Kong’s Shaw Brothers in the ’70s – eleven martial arts movies, with the wacky Mighty Peking Man thrown in for variety. Along with Eureka’s Cinematic Vengeance set, this promises a major focus on Chinese action in my early 2022 viewing schedule.

Highly anticipated, but apparently hung up in the US mail system during holiday congestion, is Severin’s big folk horror box set All the Haunts Be Ours (it was mailed weeks ago, but still hasn’t arrived in Canada). I’ve been looking forward to this for months since it was first announced. I haven’t finished watching everything in two other Severin sets: the comprehensive Dungeon of Andy Milligan, which I was enjoying but got distracted from by other options, and the Eurocrypt of Christopher Lee, which gathers mostly minor, even tangential, works of little significance to Lee’s career.

*

Martial arts

Eureka has been releasing quite a few martial arts movies, including key films starring and/or directed by the great Sammo Hung. In The Iron-Fisted Monk (1977), The Magnificent Butcher (1979), Encounter of the Spooky Kind (1980) and Millionaires’ Express (1986) it’s possible to see the part Hung played in the evolution of the genre from the more traditional style of the ’70s to the introduction of comedy and the supernatural around the turn of the decade to the large-scale action-adventure epics which led to Tsui Hark’s transformation of classic martial arts in the ’90s. There is also the influential Hung-produced Mr. Vampire (Ricky Lau, 1985).

One-Armed Boxer (1971)/Duel to the Death (1983): Eureka also released these two excellent examples of the traditional style which themselves illustrate the evolution of the genre from straightforward action to a more flamboyant, fantasy-inflected approach which defies the usual laws of physics with gravity-defying stunts.

*

Criterion

Criterion continued to anchor much of my more serious viewing, helping to salvage a degree of self-respect with a range of classics and foreign films with which I could assuage my conscience as it nagged at me for my persistent taste for trash.

The Ascent (1977)/Mirror (1975): These two poetically expressive Russian films – by Larisa Shepitko and Andrei Tarkovsky respectively – are intensely emotional meditations on the traumatic impact of 20th Century history on the Russian people.

The Human Condition (1959-61): Masaki Kobayashi’s epic depiction of one decent man’s gradual destruction by the overwhelming forces of Japanese militarism during the occupation of Manchuria in the 1930s and ’40s is one of the masterpieces of humanist cinema.

Mandabi (1968): Ousmene Sembene’s second feature is a tragi-comic fable about the complex, lingering psychological and cultural influences of colonialism on African societies.

in Jacques Rivette’s Celine and Julie Go Boating (1974)

Celine and Julie Go Boating (1973): Jacques Rivette’s playful surrealist masterpiece is a rich meditation on the nature of storytelling and the part it plays in our construction of identity.

Memories of Murder (2003): Bong Joon-ho uses a murder investigation to dissect the complexities of South Korean society as it struggled to redefine itself in the ’80s after decades of political oppression.

History is Made at Night (1937): Frank Borzage’s romantic comedy is also a tragedy of nightmarish marriage, all the more remarkable for having been patched together on the fly as it began shooting without a finished script. The work of an artist, it belies the image of classical Hollywood as nothing but a smoothly running machine driven by the studios’ thirst for profit.

Merrily We Go to Hell (1932): Dorothy Arzner deconstructs the elements of romantic comedy and exposes relationships as a toxic stew of malevolent self-interest and delusion, stripping away all the comforting fantasy Hollywood was inclined to give the audience.

Nightmare Alley (1947): I haven’t seen Guillermo del Toro’s glossy remake, but Edmund Goulding’s original is as dark as noir ever got, with Tyrone Power’s opportunistic con man eagerly digging his way to his own doom as he ruins everyone around him.

The Parallax View (1974): Alan J. Pakula’s movie is one of the key paranoid thrillers of the post-Watergate era, stylish and cynical, with Warren Beatty perfectly cast as a man whose absolute self-confidence in a world of violence and deceit inevitably leads him to destruction.

Streetwise (1984)/Tiny: The Life of Erin Blackwell (2016): A remarkable documentary about the lives of kids living on the streets of Seattle, which takes their own view of themselves rather than a clinically detached perspective. The disk includes subsequent films which follow one of the kids into adulthood, creating a portrait of on-going generational trauma.

Original Cast Album: “Company” (1970): A timely release of D.A. Pennebaker’s record of the long gruelling session to record the performances of the cast of Stephen Sondheim’s Company immediately after opening night. An illuminating examination of the creative process and just how much work goes into conveying an impression of effortlessness.

Criterion has recently released a number of movies by Black filmmakers, both from the first wave of the late 1960s and ’70s and the second wave of the late ’80s and ’90s. The former are represented by Gordon Parks’ The Learning Tree (1969) and a box set of Melvin Van Peebles’ features (1967-72, which I have still to get to), the latter by Bill Duke’s Deep Cover (1992) and the Hughes Brothers’ Menace II Society (1993). These releases are beginning to fill in a major gap in the cinematic record available on disk.

*

Other notable releases

Dementia (1953): The BFI did a nice job with John Parker’s one-of-a-kind poverty row classic, a nightmare steeped in perverse psychoanalytic tropes rendered in expressionist imagery rooted in German silent cinema and the seedier tendencies of film noir. The Blu-ray includes, as it should, both the original silent version as well as the Daughter of Horror (1957) variant with overwrought narration, plus a commentary by Kat Ellinger and a few other extras.

I Start Counting (1970): Also from the BFI, David Greene’s working-class psycho-thriller features Jenny Agutter, just before she became a star in The Railway Children and Walkabout, as a girl prone to romantic fantasies who begins to suspect that her older stepbrother may be the rapist-murderer terrorizing a new town on the western fringe of London. More character study than mystery, the film nonetheless builds considerable tension as the girl’s illusions put her increasingly in danger.

Under the Shadow (2016): Babak Anvari’s horror-fantasy, set in post-Revolution Iran, draws on ancient myth to create a potent allegory of political oppression as a woman and her young child are trapped in their apartment in a war-torn city and find themselves under attack by a malevolent djinn. The film gets an excellent presentation from Second Sight, supplemented with interviews and an earlier short film by Anvari.

The Criminal Code/Twentieth Century: Indicator released these two early Howard Hawks features on Blu-ray, neither of which I’d previously seen. The Criminal Code (1930) is an intense expression of outrage against injustice, with a D.A. made warden of a prison many of whose inmates he himself had put away. Just a few years later, with Twentieth Century (1953) Hawks launched his parallel career as a maker of fast-paced screwball comedies with a cynical bite, putting two equally unlikable characters (a Broadway producer and his former lover and star) together on a speeding express to shred one another with acid wit on the way to discovering that they really do belong together.

First Cow (2020): Kelly Reichardt turns her attention from complicated women to the friendship between two men on the 19th Century frontier in this wonderfully observant tragi-comedy which revolves around housekeeping and cooking.

Daughters of Darkness (1971): Harry Kuemel’s sumptuous and languid meditation on life, sex, death and vampirism has never been done full justice on disk before (the rich colours always seemed just beyond reach of the available technology), but Blue Underground’s 4K restoration looks spectacular. The extras from previous editions are carried over along with a new commentary from Kat Ellinger.

Who Killed Captain Alex? (2010)/Bad Black (2016): This AGFA release (from 1919, though I only came across it this year) should inspire anyone who has the urge to make their own movies. Nabwana I.G.G. and his friends make action movies in Uganda for budgets of about US $200 – and that includes car crashes, martial arts fights, gun battles and helicopter attacks, along with digital effects. These home-made epics are absurdly entertaining and AGFA has packed the disk with an excessive amount of ephemeral material.

in Chris Caldwell and Zeek Earl’s Prospect (2018)

Prospect (2018): Although digital techniques have made it possible for filmmakers to be ambitious on a low budget, too many neglect the creative aspects of production. Script, cast, and an expressive use of camera and editing are actually more important than digital image-making and Zeek Earl and Chris Caldwell get everything right in their independent sci-fi movie, focusing on a handful of characters struggling to survive on a beautiful but deadly moon, with a resourceful young woman coming-of-age as the adults around her prove unreliable. With limited resources, the writer-directors evoke an imaginative world which extends beyond the immediate story – the excellent CGI is icing on the impressive cake.

Deadlock (1970): Roland Klick’s tight little movie blends film noir and the spaghetti western in a bleak desert setting as three men engage in a deadly cat-and-mouse conflict over a bag of stolen money. Klick takes genre cliches and transforms them into an exhilarating drama of self-destructive masculinity.

Six String Samurai (1998): Lance Mungia’s debut feature is another genre-mix, a martial arts/spaghetti western/musical/post-apocalyptic adventure shot in Death Valley. It may be a matter of personal taste, but I loved every minute of it.

Eloy de la Iglesia: Severin’s release of five movies (Cannibal Man [1972]/No One Heard the Scream [1973]/Navajeros [1980]/El Pico 1 & 2 [1983-84]) by Basque filmmaker Eloy de la Iglesia is a substantial introduction to a previously unknown (to me, at least) director whose work incorporates genre elements with increasingly bitter social commentary spanning the last days of the Franco dictatorship and the years of Spain’s difficult redefinition as a democracy.

Filmworker (2017): Tony Zierra’s documentary portrait of Leon Vitali, a talented actor who abandoned his career in order to devote his life to Stanley Kubrick, is a fascinating psychological study in self-effacing obsession. The overall effect is deeply melancholy and ultimately puzzling, with Vitali’s sublimation to Kubrick’s demands taking on the quality of a kind of secular religion.

*

Finally, the highlight of the year for me came courtesy of Vinegar Syndrome and Severin, with each company releasing a definitive 4K restoration of one of Paul Morrissey’s wonderful Gothic horrors – Severin put out a 4K UHD/Blu-ray/CD combo of Blood for Dracula (1974) back in the summer with almost four hours of cast and crew interviews, while VS went all out on Black Friday with a three-disk 4K UHD/Blu-ray release of Flesh for Frankenstein (1973) offering a 4K disk, a Blu-ray with both digital and anaglyph 3D options, plus a Blu-ray with a flat presentation plus commentary and almost four hours of cast and crew interviews. I first saw these movies during their original theatrical releases almost five decades ago, but since then all I’ve had to reinforce my fond memories are Criterion’s DVD editions from 1998 – which now seem almost unwatchable with their non-anamorphic, letterboxed transfers. It’s been a long wait, but Severin and VS have made that wait worthwhile with the lavish attention they’ve paid to both movies.

Comments