Recent disks from England, part one

“Recent” here doesn’t strictly mean new releases as I continue to catch up with titles which came out a year or two ago. But they’re all new to me. Arrow had a big December sale, so I filled a few holes in my collection; I also took advantage of a few deals on the Indicator and Eureka websites.

Eureka

Buying always outstrips time available for viewing, so my big stack of Fritz Lang titles from Eureka sits there untouched in hopes that some day I’ll be able to set aside a week or two to immerse myself. Meanwhile, after the Joseph Kuo box set, I blasted through Eureka’s Sabata Trilogy and Tsui Hark’s Zu: Warriors from the Magic Mountain.

The Sabata Trilogy (Gianfranco Parolini, 1969-71)

The spaghetti western was already in decline by the end of the ’60s; as with any genre approaching old age, it was sliding towards pastiche and parody, reiterating familiar tropes frequently without finding anything new to do with them. The Sabata Trilogy, all directed by Gianfranco Parolini under his Frank Kramer pseudonym, draw on memories of Sergio Leone’s Man with No Name trilogy – a deadly stranger arrives in town, gets caught up in local conflicts and plays factions against one another on the way to pocketing a fortune. Those echoes are amplified here by the casting of Lee Van Cleef as Sabata in Sabata (1969) and Return of Sabata (1971), the first and third movies (replaced by Yul Brynner in the second, Adios, Sabata [1970]), drawing on his image as Colonel Mortimer in For a Few Dollars More (1965). But the sense of discovery in Leone’s movies just five years before, is replaced by a kind of creative laziness – things happen, but characters are barely sketched in. Events are inserted into perfunctory plots because they will be familiar from other movies, not because they have any real narrative imperative of their own.

To increase the sense that all this is little more than costumed play, Parolini adds overt elements of the circus – acrobats and performers are a part of the game, aligning these movies more with the mockery of Enzo Barboni’s Trinity movies, made around the same time, than the classic westerns of Leone, Corbucci and others. The third movie even opens with a self-consciously theatrical shootout in a barn, artificially lit and emphasizing Sabata’s super-human abilities as he dispatches a whole gang of gunmen – all of it turning out to be a performance for a paying audience.

Although Van Cleef and Brynner bring their own history as western stars to bear, and Paroloni stages much of the action well, these movies never provide the fully satisfying entertainment you get from something that takes itself more seriously. I have the same reaction to the Sartana movies. Although many spaghetti westerns had a comic streak, this was most successfully incorporated in particular characters (Eli Wallach in Leone’s movies, for instance), while the surrounding narrative was played straight, the violence presented seriously. Character in the Sabata movies is more two-dimensional, there simply to facilitate the cartoonish plots.

Zu: Warriors from the Magic Mountain (Tsui Hark, 1983)

A key figure in the Hong King New Wave, Tsui Hark began his career by disrupting the established film business in HK, his first feature, The Butterfly Murders (1979), blending martial arts and horror; his second, We’re Going to Eat You (1980), mixing comedy with cannibals; and his third, Dangerous Encounter First Kind (aka Don’t Play with Fire, 1980), treating disaffected youthful rebellion with nihilistic violence so intense that the authorities cracked down and he was forced to reshoot much of the film. An enfant terrible, he tackled numerous genres with audacious irreverence, equally comfortable with comedy, action, romance and violence, sometimes all in the same movie.

His real commercial breakthrough came with Zu: Warriors from the Magic Mountain (1983), a radical revision of the martial arts genre which flew head-on into fantasy, pitting its heroes (a monk and his acolyte, a swordsman, and a peasant soldier) against powerful gods engaged in a war between Good and Evil with the fate of the human world at stake. With elaborate sets, extensive wire-work which enabled the characters to fly all over the place, and elaborate if not very convincing animation and optical effects, Zu infuses a classical genre with a pop culture sensibility, stripping it of its formal ritual qualities and infusing it with an absurdly playful energy. This radical break with established conventions revitalized martial arts cinema and led to the international success of such films as Ronnie Yu’s The Bride With White Hair (1993), Ang Lee’s Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000) and Zhang Yimou’s series of historical epics, beginning with Hero (2003).

Tsui went on to make dozens of movies in various genres (including a brief foray to Hollywood in service of Jean-Claude Van Damme), repeatedly returning to the martial arts genre, but his biggest influence has been as a prolific producer, not least on John Woo’s breakthrough A Better Tomorrow trilogy (1986-89) and The Killer (1989). But Zu remains a crucial movie in his filmography, blending Chinese traditions with a style and attitude imported from the West. While the technical abilities of the Hong Kong industry may not have been quite equal to Tsui’s ambition, that ambition is on full display and his audacity overcomes the inherent limitations of some of the film’s special effects, paving the way for even more ambitious movies which appeared throughout the ’80s and ’90s.

*

Indicator

Gray Lady Down (David Greene, 1978)

One of the great benefits of art and literature is that through them we can experience many things for which there would otherwise be no opportunity. These vicarious experiences provide access to thoughts and feelings we might not actually want in reality, but can enjoy at this safe distance. Who would really want to go through the tension and anxiety provoked by a horror movie, or the violence and insecurity of war? But being given emotional and intellectual access through books and movies can enlarge our understanding and even, if we are receptive, increase our empathy for those who do in fact experience such things directly.

I’ve been lucky enough to have a relatively stress-free life, which is perhaps why I enjoy being subjected to terrible things in movies which I know will end and leave me unscarred. In fact, the greater the distance from personal experience, the more I can enjoy imaginary danger and fear. On the other hand, having been in two serious car crashes, bad driving in movies provokes genuine anxiety. I actually felt physically sick when I saw Paul Thomas Anderson’s Punch-Drunk Love (2002) because he somehow captured exactly the feeling of being in a crash and it triggered deeply embedded traumatic memories.

Anyway, all this is by way of explaining that although I would never want to be on a submarine, I really like submarine movies – the sense of claustrophobia, of imminent danger, are things I would hate in reality, but love in a movie. Which is why I appreciated David Greene’s Gray Lady Down when I saw it in a theatre in 1978 and liked it again when watching it on Indicator’s new Blu-ray. It didn’t get good reviews when it came out, the biggest complaint being that it’s too cliched. True, there’s a by-the-numbers quality, with stock characters fulfilling their designated narrative purposes.

But for me that facilitates an appreciation of the core situation: the feeling of being trapped in a hopeless predicament with virtually no chance of survival. This is a “process” movie in which a lot of serious men react to a situation and try to figure out the best way of resolving each difficulty as it arises. The crew of the crippled submarine, resting precariously on an unstable ledge above a deep sea chasm, can do little but wait and hope, some of them stoic, others cracking under the strain, while above them the crew of a rescue ship look for a way to get the survivors out before the hull is crushed by external pressure or the oxygen runs out.

There are disagreements and friction between by-the-book officers and the insubordinate inventor of a deep-sea vehicle from which the rescue mission can be guided – but eventually the demands of the mission overrule these personal conflicts and everyone goes above and beyond individual limitations to accomplish the impossible. The pleasures of Gray Lady Down are those which come from watching people do a difficult task, step-by-step, coming to terms with the cost and at crucial moments willingly sacrificing themselves for the greater good.

Nothing new here, it’s true, but as with any story what matters is the telling and Greene tells it very well, aided by decent model effects and an excellent cast headed by Charlton Heston, Ronnie Cox, Stacy Keach, Ned Beatty and David Carradine.

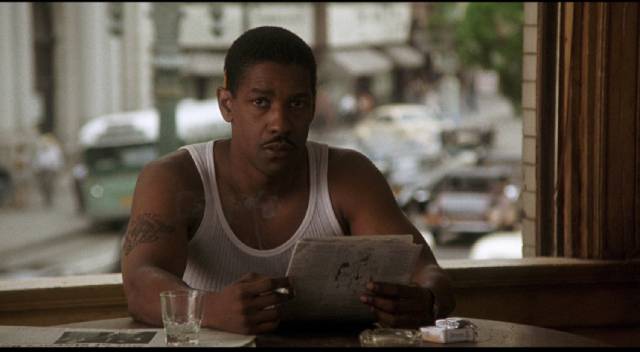

Devil in a Blue Dress (Carl Franklin, 1995)

Carl Franklin’s adaptation of Walter Mosley’s first Easy Rawlins novel bears a strong resemblance to other neo-noir detective movies, like Roman Polanski’s Chinatown (1974) and Curtis Hanson’s L.A. Confidential (1997), substituting the period glow of Southern California sunlight for the chiaroscuro expressionism of classic noir and using the narrative to expose layers of interconnected personal and political corruption. What Devil in a Blue Dress (1995) adds to the mix is race – something barely visible in Chinatown and L.A. Confidential.

Rawlins (Denzel Washington) fought in World War Two and is trying to hold on to a small part of the American Dream he was supposedly risking his life to protect. He has a small house in a vibrant Black community in Los Angeles, but he’s lost his job at an aircraft plant, apparently because he wasn’t sufficiently deferential to his white boss, and now his material existence is threatened because he can’t make the mortgage payment. Perhaps too fortuitously, his barkeep friend Joppy (Mel Winkler) connects him with a guy named Dewitt Albright (Tom Sizemore), who wants to hire Easy to find a missing woman. The money is too good to turn down, even though there’s something a bit off about the overly friendly and cheerful Albright.

Needless to say, Easy’s search leads to increasingly dark places, spanning from the Black community to the mansions of the rich and powerful, specifically two rivals in the upcoming election for mayor. As Easy crosses various invisible lines – those between Black and white and between rich and poor – he encounters prejudice and violence at the hands of racist cops and gangsters; people end up dead and it’s clear that Easy is being set up to take the fall. Society is corrupt from top to bottom, but being Black makes a person particularly vulnerable; the law shelters and protects wealthy whites, no matter how despicable their crimes, but there’s no security for an honest working class Black man.

The narrative is convoluted, as it should be, and Franklin captures a fine sense of period. Although Washington may be a bit too much of a nice guy, the cast is packed with fine actors who evoke a constant threat of danger – Sizemore, Maury Chaykin, Jennifer Beals and particularly Don Cheadle as Easy’s wartime buddy Mouse who lacks any restraint when it comes to violence, ready to hit, choke or shoot anyone who happens to get in his way.

The Sinbad Trilogy (Various, 1958-77)

Indicator recently re-released their box set of Ray Harryhausen’s Sinbad Trilogy as a 5th anniversary limited edition (the original set was dual format, but the reissue is Blu-ray only). I missed the original release, but decided to pick up this new edition. As with all Indicator’s box sets, it’s beautifully produced and includes an 80-page book of essays about the movies. This is essentially a nostalgia purchase. Some of my earliest memories of going to the movies come from Harryhausen’s work – for decades, my memory conflated The 7th Voyage of Sinbad (1958) and Jason and the Argonauts (1963) and I’d be surprised when watching one of them on TV when a certain sequence would seem to be missing, though I eventually realized that it was from the other movie.

With all of Harryhausen’s movies what really matters is the effects sequences – in some ways it’s too bad that Harryhausen himself and his frequent producer Charles Schneer felt that way too, paying less attention to scripts and directors. Occasionally Harryhausen’s animation served the story (say in Cy Endfield’s Mysterious Island [1961] or Nathan Juran’s First Men in the Moon [1964]), but mostly story existed merely to hang the effects sequences on.

Each of the Sinbad movies – Nathan Juran’s The 7th Voyage of Sinbad, Gordon Hessler’s The Golden Voyage of Sinbad (1973) and Sam Wanamaker’s Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger (1977) – sends the heroic sailor on a dangerous quest triggered by the menacing actions of a malevolent magician or witch whose dark magic requires some mythical object to counteract its effects. These villains are all well-played by Torin Thatcher, Tom Baker and Margaret Whiting respectively, while there’s always an attractive heroine along for the trip who can look suitably decorative in quieter moments and just as suitably awed and frightened when confronted with Harryhausen’s monsters – Kathryn Grant, Caroline Munro and Jane Seymour respectively.

There are inevitably repetitive sequences from film to film – 7th Voyage’s swordfight with a skeleton (expanded in Jason and the Argonauts) is echoed in Eye of the Tiger when the evil Zenobia (Whiting) conjures three insect-like critters from a fire (which in turn resemble the Selenites in First Men in the Moon); the fight between dragon and cyclops in 7th Voyage is reiterated in Golden Voyage between a centaur and a griffin and in Eye of the Tiger between the troglodyte and the sabre-toothed tiger. The flying homunculus in Golden Voyage is essentially a repurposed Ymir from 20 Million Miles to Earth (1957), not to mention a replay of the harpies from Jason. But we don’t necessarily go to a Harryhausen movie for originality; the pleasure lies in the display of his craft, and each of these Sinbad movies has multiple displays of his skill with stop-motion and often impressive optical work blending the miniature creatures with live action. There are, however, also instances of very dicey compositing, with sub-par matte work. (Ironically, the worst of these turn up in Eye of the Tiger and don’t even involve Harryhausen’s animation; there are some really bad medium shots and close-ups putting the actors in front of background plates filmed on location.)

Apart from the conjuring of nostalgic memories, the real charm of these movies lies in their hand-crafted quality. They are an expression of the imaginative possibilities of one man’s intensive labour – their very lack of “realism” is their strongest asset, the investing of a simulation of life into inanimate figures far more impressive than the glossy photorealism of CGI, their imperfections a sign of the craftsman’s work. For all their faults as movies, these films still stir a viewer’s imagination. Fantasy doesn’t need to be “realistic” to be satisfying.

Next: new disks from Arrow…

Comments