David Lynch’s Dune redux

For obvious reasons, my relationship with David Lynch’s Dune (1984) is unlike what I have with any other movie. Perhaps if I had gone on after my time on set in 1983 to work on other big movies, it would have lost some of the ground it occupies in my mental landscape. But that didn’t happen. It was six years after my experience in Mexico that I began to make short films of my own, and another six years before I began a career as a professional film editor. Even then, I mostly worked on documentaries, with only two very low budget features along the way. So Dune stands as my sole experience on a big budget studio feature.

But that alone doesn’t fully explain my attachment. What was really important was that this was specifically a David Lynch production. For complicated, not entirely explicable reasons, Lynch holds a unique place in my life. I was so powerfully affected by Eraserhead (1976) that that strange movie altered the course of an until-then unexceptional life. My obsession with the film led to my meeting with Lynch and writing about him and his movie, and that in turn led to me being hired as part of a documentary crew assigned to record six months of intensive work in Mexico during which Lynch wrestled with a behemoth over which he didn’t have complete control, and which ended up being his most painful experience as a filmmaker.

There are many reasons why Dune ended up a commercial and critical failure; there are also many reasons why the movie went on to gather an enthusiastic fan base and many decades later has undergone a tentative critical reevaluation. At the centre of these reasons, of course, is Lynch himself. He began the project as an outlier, an odd, arty independent filmmaker with just two idiosyncratic black-and-white movies behind him. Dune proved to be a devastating trial by fire which made clear that he wasn’t going to become a mainstream director, that his personal taste and passions worked against commercial imperatives.

And yet, the experience did introduce him to a production system which, in other circumstances, could support rather than work against him. For whatever reason, Dino De Laurentiis didn’t abandon Lynch after the failure of Dune; instead he provided a small but adequate budget for a project as personal as Eraserhead, but with its strangeness contained in what appears to be a more accessible, almost mainstream narrative world. If Dune had been seen as a personal failure for Lynch, baffling audiences and critics, Blue Velvet (1986) launched him in a new direction, one which has established him as a pop culture icon whose idiosyncrasies have been embraced, influencing countless other filmmakers who strive to infuse their own work with Lynchian weirdness.

As for Dune, what were originally perceived as its failures – specifically all those Lynchian touches in design and the almost abstract storytelling – are the very things which are now appreciated. De Laurentiis and Universal had wanted to launch a new franchise on the model of Star Wars, but they hired the guy who had made Eraserhead and The Elephant Man (1980). And then they fought against the very things which made Lynch distinctive, not only trying to force the movie into an action-fantasy mould, but also crushing its massive, sprawling narrative into a ridiculous 135 minutes. They hired Lynch for his distinctive personal artistry and then were confounded when that’s what he delivered. If De Laurentiis hadn’t financed Blue Velvet, the blame heaped on Lynch for Dune’s failure might have ended his career before it really got going. With his subsequent successes, it’s the Lynchian elements which fans now appreciate about Dune, despite its undeniable status as a broken film, an unfulfilled promise.

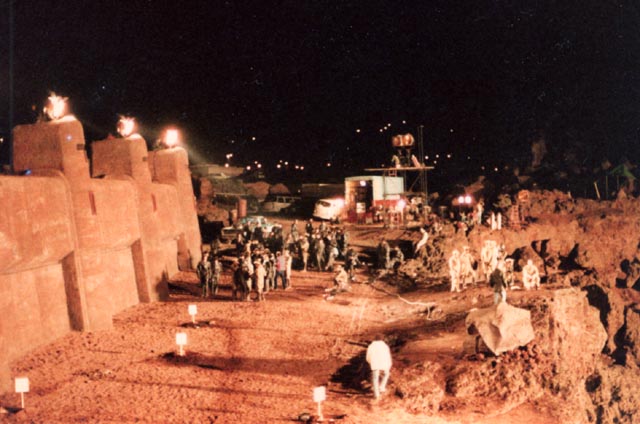

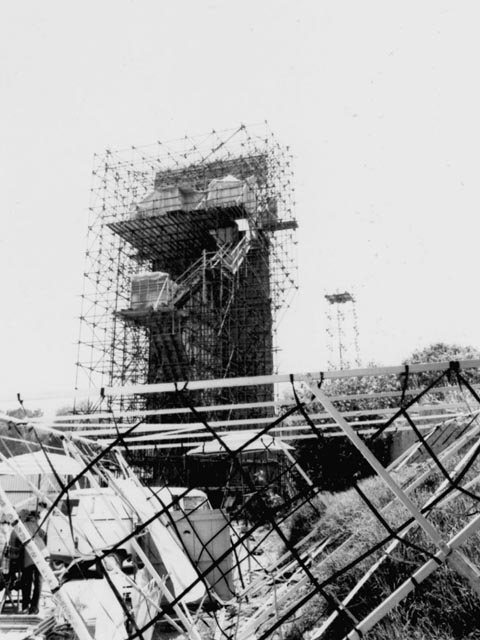

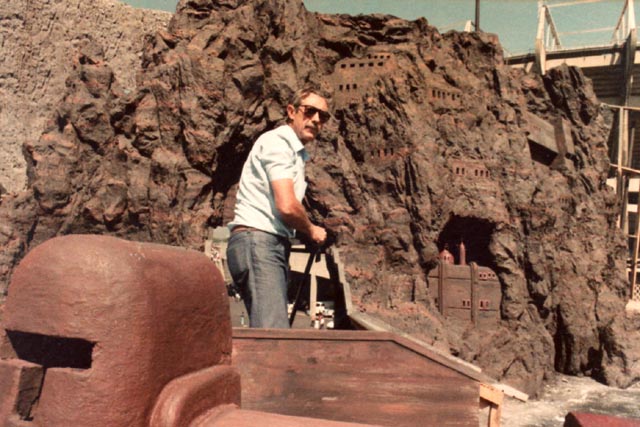

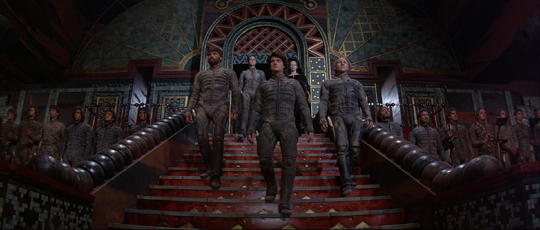

While recognizing that brokenness, I have been very fond of Dune ever since I first saw it in late 1984. I appreciate the richness of its design, the density of its world-building. It remains even now one of the most visually impressive fantasy films ever made (and made without the assistance of computers). But beyond that there’s my personal connection; I stood on all those sets, I watched those scenes being filmed … and I can fill in so many gaps with memories of the many scenes filmed which were stripped out in the brutal act of compressing the film to its mandated running time.

This is perhaps the most baffling aspect of the whole story, because the shooting script so obviously dictated a much longer film. De Laurentiis and Universal approved that script, they approved the construction of all those sets, the hiring of all those actors, and then forced Lynch and editor Tony Gibbs to strip out entire sections, to transform whole stretches of narrative into brief montages – in effect, to tear the guts out of what had been shot. The production of Dune was almost from the start an absurd comedy of cross-purposes, a commercial enterprise whose backers had tried to cash in on the prestige of an artist beginning to be recognized for his originality while simultaneously determined to rein in that originality, to somehow harness it for their own commercial purposes. Meanwhile, Lynch was using their vast resources to explore his own interests. In retrospect, it’s impossible to see how anyone thought this could end well.

I’m mulling over these thoughts yet again because I just re-watched Dune for perhaps the fifteenth time, having bought it once more for the eighth or ninth time. No doubt this has been a continuing attempt to maintain my personal connection with an experience I had almost forty years ago; maybe deep down there’s an irrational hope that something new might yet be discovered. Well … maybe not so irrational after all, but I’ll get to that in a moment.

I first bought the movie as a letterboxed VHS tape in the ’90s, then a few years later on laserdisk. Then along came DVD, and I bought each edition I could find – US release, British and French releases. One thing I was looking for was signs of the survival of the video material recorded by cameraman Anatol Pacanowsky and myself on set in Mexico, but initially all that came along was the promotional short put together during production by publicist Paul Sammon for screening at sci-fi conventions. Then in the early ’00s there were some retrospective interviews (but never Lynch!) and an assortment of deleted scenes with their tantalizing suggestion of what might have been.

Multiple editions also included the “extended cut” made by Universal for television, a depressingly incompetent piece of hackwork done by people who didn’t have a clue what they were doing. Nonetheless, it did provide glimpses of what had been stripped out of the theatrical cut, although poorly used. With Lynch’s name removed (it was “directed by Alan Smithee”) and Lynch’s own erasure of the movie from his filmography, it seemed certain that we would never see a true reconstruction of Dune, and a director’s cut was out of the question.

Announced back in 2020 but delayed (partly due to Covid?), Lynch’s Dune has been given a new 4K polish by Koch Media in Germany. This first appeared last Fall from Arrow Films in the U.K., and I had to buy it even though scheduling issues caused Arrow to drop Daniel Griffith’s making-of doc (for which I’d been interviewed). Needless to say, the new transfer is the best the film has looked on video. But I nonetheless couldn’t be satisfied to stop there, because Koch Media were releasing their own 4K edition with even more comprehensive extras – including Griffith’s doc. Because rights issues limited that release to the EU, obtaining a copy was a bit complicated – and expensive – but having finally received my copy a couple of weeks ago I can say it was more than worth the wait and the cost.

The Koch ultimate edition includes seven disks, a book of production photos and a comic book adaptation (the latter two unfortunately only in German). Some of the extras are not English-friendly, which is a pity – long interviews with Jurgen Prochnow and Giannetto De Rossi aren’t subtitled – but Griffith’s featurettes on the Toto score and the bizarre merchandising are there, along with that much-anticipated making-of, The Sleeper Must Awaken. Unable to rein in my ego, the latter was the first thing I watched.

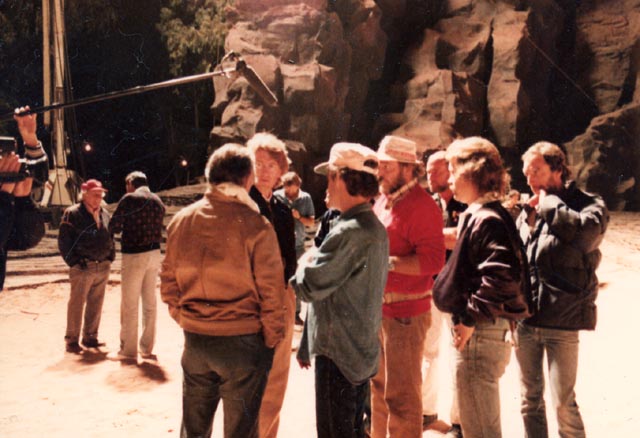

Like Dune itself, the doc feels somewhat rushed and compressed, jamming as much as possible into 82 minutes while covering the history of the various aborted efforts to adapt the book, how it eventually ended up in De Laurentiis’s hands with Lynch writing and directing. There’s a lot of nuts-and-bolts material about the design and construction of the sets at Estudios Churubusco, casting, wardrobe, special effects – all done without talking heads, but rather having new and archival interviews play over visuals including clips from the finished film, production artwork and stills. Even with so much squeezed in, I’d like to see an extended cut!

As for my part in this, I’ll just say that I’m not embarrassed when my voice pops up for a few clips in the final twenty minutes, and I was pleased that Daniel found quite a bit of use for personal stills I had provided and that he was able to pull some clips from some of the audio recordings I had salvaged from the 1983 video material.

After watching the doc, I turned to what may be the most unusual extra I’ve ever encountered on an official release. I was aware of a fan edit of the film floating around on-line, but had never made an effort to find and watch it. I know very little about the whole fan edit subculture, but understand the impulse – I have often watched movies and thought there were things I could improve. But having already seen the mess of the TV version, I didn’t think there was a lot of potential for this unauthorized version.

Well, I was wrong there. The anonymous editor who goes by the name Spicediver apparently worked on this project for years, going through three versions, resisting at first and then accepting criticism from fellow Dune aficionados. His (or her?) final version runs as long as the TV cut, but is worlds away from that abomination. Working with the theatrical cut, the TV version and the deleted scenes included on some DVD editions, the editor has done far more than simply drop new material into the official release. This is a thoughtful, considered re-edit, at times shifting the order of scenes, deleting quite a lot of the inner voices which the theatrical cut used in a not entirely successful attempt to clarify the narrative, and changing the ending to remove the baffling coda of the original which violates the story’s central point – if Paul makes it rain on Arrakis, the worms will die and the spice will disappear.

Watching Spicediver’s cut, I was frequently surprised and occasionally shocked by how much he had managed to flesh out sequences, adding both narrative and character detail – perhaps more surprised that this expansion included the already long first half and not just the brutally compressed second half after Paul and Jessica are taken in by the Fremen. The flow of the movie is improved with this extra breathing room. But crucially, this editor has restored much of the detail about Fremen culture which was lost in the theatrical cut, beginning with that first encounter, the knife fight between Paul and Jamis, and the importance of Paul’s “giving water to the dead” after killing for the first time.

This version expands on the richness of Lynch’s world-building – a remarkable feat considering that Spicediver didn’t have access to everything that had been shot, but only the scraps made available on various video releases (which of course means the quality is variable). Although this fan edit is obviously not a “director’s cut”, it does serve the crucial purpose of showing that there was a coherent, entirely comprehensible movie in the material which Lynch shot. This settles the question, if it needed settling at this point, of where blame truly lies for Dune’s creative and commercial failure: whatever you might like to argue about Lynch’s stylistic choices, the clumsiness and lack of clarity of the theatrical cut was due to the short-sightedness of De Laurentiis and Universal, who sabotaged the film’s commercial potential for the sake of a completely arbitrary decision that it must not exceed 135 minutes.

Seeing this, it seems even more disappointing that we’ll never get a genuine David Lynch director’s cut – such a version, whatever its inherent flaws, would go some way towards restoring Dune as a key step in Lynch’s development as a filmmaker. Short of that, I’m enormously grateful for what Spicediver has accomplished. I have no idea what convoluted rights issues were involved in Koch licensing this unauthorized version for their release, but I salute the lawyers who put the deal together.

Having watched this version, I went on to re-watch the theatrical cut again and was startled to realize just how choppy and awkward it is – something that years of familiarity had obscured for me. I immediately missed so much of what I’d just seen in the Spicediver cut and realized that this illicit version will be my go-to whenever I feel like seeing Dune again; given the compromised nature of the theatrical cut, I don’t see this as any kind of betrayal of Lynch. (And there’s certainly no need ever to watch the TV cut again.)

The set itself beats Arrow’s release hands down. Disks one and two have the theatrical cut in 4K UHD and Blu-ray (while Arrow also offer this, they add a lot of archival extras rather than devote the entire disk to the feature); disk three has the new bonus material (Griffith’s documentary plus the featurettes on the score and merchandising, and the interviews with Prochnow and De Rossi – the Arrow does include the De Rossi interview, with subtitles, but not the Prochnow); disk four has five hours of archival video and audio extras, which includes everything from previous editions plus more – but unfortunately not the behind-the-scenes featurettes made for TV at the time of the film’s release (which recently turned up on YouTube); disk five has the extended television version; disk six is the Spicediver fan edit; and disk seven is the soundtrack CD.

The Arrow edition does have a couple of extras not included on the Koch (so much for “ultimate” editions!), most importantly a couple of commentary tracks by Paul Sammon, who worked on the production as a publicist, and Mike White of the Projection Booth podcast.

I think I can probably stop buying Dune now – these two restored editions have sated my appetite and, thanks to the Spicediver cut, finally put an end to four decades of frustration, the sense of something lingering unfinished. Not perfect, by any means, but good enough to quell an unfulfilled longing.

Comments

How was the quality of both the tv and spiced diver cuts as far as video and audio quality? Does it feel like a high res hd quality edition with really solid blacks and definition or more like a upscales section tv cut? Audio as well? Fascinating read…you got me sold!

I can’t say for the TV cut because I haven’t re-watched it. The Spicediver cut is overall very good quality, though uneven because additional material had to be drawn from inferior sources such as lower-res disk extras. Audio quality seemed fine to me, though I don’t have a high-end sound system which might pick up differences from the official release.

You might like to know, Mr. Godwin, that Spicediver recently rebuilt the edit in 1080p high definition, drawing from 94% 1080p sources and improving certain special effects sequences, improving color correction, as well as a small number of minor additional editing changes. These improvements even out the variable quality somewhat. It can be found on YouTube, but it’s blocked in certain countries.

Hi, yes I’ve already come across it. Really appreciate what Spicediver has accomplished with a movie that’s really important to me personally.

Hello, I’d really like thank you for your blog and excellent writing. I’m thrilled to have discovered this part of the internet. Especially the insight on Spicediver’s work – after even a few minutes glimpse I cannot wait to watch this this evening.

All the best, Kevin @ roxymusicsongs.com

Thanks, Kevin … that’s the main reason I keep this going, to help other people find things I think are worthwhile.

Just took a look at your own blog … as a long-time fan of Roxy Music and the band members’ solo careers, I’ll definitely have to spend some time on your site!

Coming from a writer of your stature that is indeed a compliment. I am going through (yet another) intense David Lynch stage now and your blog is my starting point. Keep up the great work!

Cheers

Kevin

Thanks for your blog.

I saw Dune when it was released in 1984 at the age of 12 and it left a strong impression on me that is still there today. Everything fascinates me about this movie and I think it’s the one I’ve seen the most in my life. Despite its imperfections, I like everything about this film, including the music, which in my opinion is one of the best made for cinema.

The characters and the actors are wonderful and I have a facination for Baron Harkonnen as well as the representative of the space guild. Too bad the name of the actor is not credited anywhere because he participates in the unhealthy atmosphere of the Guild. Do you have any information about him?

Cordially.

patrick

Hi. The Guild spokesman was played by Arturo Garciarubio, who was an assistant director drafted to play the part, not an actor. He was also, having been a TV news cameraman, the technician who looked after the video equipment Anatol Pacanowski and I were using to document the Dune production. A number of crew members were used as extras and bit players and it’s one of my regrets that I wasn’t included in their number, despite being on and around the set for six months!

Hy,

thank you very much for this information.

I understand your regret!