Tobe Hooper’s mangled career

When a filmmaker hits it big early in his or her career, they sometimes have a hard time following through commercially and/or critically because they’ve created a very particular set of expectations. No doubt the most obvious example of this is Orson Welles, who after the enormous impact of Citizen Kane (1941) spent his life struggling to make movies while almost continuously receiving the disdain of critics – and the sneering contempt of an industry which seemed unable to forgive a young upstart for shaking up their comfortable status quo – all while creating a remarkable body of work despite the financial and logistical problems he had to contend with. Even now there are those who deem him a monument to failed potential because almost everything he did he did outside the industry which had rejected him. Objectively, that lack of institutional support actually makes his achievements all the more impressive.

Although only glancingly comparable, Tobe Hooper struggled through a three-plus decade career after helping to transform the horror genre with The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974). Like George A. Romero’s Night of the Living Dead, released six years earlier, Hooper’s movie (co-written with Kim Henkel) firmly situated horror in a recognizable contemporary world rather than in another time and/or place which provided a comfortable distance for the audience from the violence on screen. Perhaps more importantly, Chain Saw eschews all fantasy, its horror residing in human pathology rather than the supernatural (despite the sci-fi gloss given Romero’s zombies, the reanimated dead are by definition not realistic).

Audiences (and critics) who had appreciated Chain Saw were puzzled and largely disappointed by Hooper’s next movie, Eaten Alive (1976). Gone was the apparent realism, replaced by artifice and a tone which exaggerated characters and events into the realm of black comedy. People were baffled. And yet a look back at Chain Saw reveals the seeds of this seemingly inexplicable change of direction. The central scene of the earlier movie, in which the desperate heroine joins the cannibal family for dinner, has the same comedic edge, the same sense of theatricality – it’s just less noticeable because of what surrounds it. In Eaten Alive, it seems that Hooper gave full reign to what interested him most – something which shows up in much of his subsequent work, and something which many viewers and critics continued to reject because they were looking for what they believed was the essence of Chain Saw: horror presented as a raw, real-world experience.

This tension actually exists within many of Hooper’s movies – the pull of his personal creative instincts and preferences working against genre dictates and audience expectations. At its best, this produced strangely entertaining films, but perhaps too often the results were derailed because of an apparent disinterest in the basic mechanics of genre storytelling. More than once, Hooper was removed from a project and replaced by another director (The Dark [1979], Venom [1981]), and most famously, although he did receive the on-screen credit, everyone thought that Poltergeist (1982) was really directed by producer Steven Spielberg. (Despite all the very Spielbergian elements, I see a good deal of Hooper’s visual style in the movie, if not much of his directorial personality – not surprising, perhaps, given that he was a director-for-hire on a bigger-budget studio project.)

My personal favourite among Hooper’s movies is Lifeforce (1985), in which the theatricality, the overwrought performance style, meshes perfectly with the genre narrative; here Hooper had the financial and technical resources to mount the apocalyptic story without having to cut corners. Lifeforce may be sci-fi pulp, but it has a sense of scale and complete conviction in the story it’s telling. There’s an air of madness which envelops the characters, justifiable given the narrative, which the cast play with total conviction; however absurd things might get, no one stoops to mockery. For me, Lifeforce is the perfect expression of Hooper’s cinematic art, its fullest realization.

One of the most distinctive characteristics of Hooper’s filmmaking is his obvious love of shooting on sets, something which at first seems counterintuitive given the rural naturalism of Chain Saw. But given the heightened theatricality of the performances in most of his movies, this penchant for the artificiality of sets is more comprehensible. Hooper wasn’t drawn to realism, but to the exaggerations and distortions of a purely constructed imaginative space. This is as true of the seedy swampside motel in Eaten Alive and the gaudy carnival of The Funhouse (1981) as it is of the city of London and indeed England itself in Lifeforce, the small town of Invaders from Mars (1986) and the vast underground scrapyard of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 (1986).

It’s also true of his last feature to receive anything more than a perfunctory theatrical release before a ten-year retreat into television: The Mangler (1995), adapted from a story in Stephen King’s 1978 Night Shift collection. The rights had passed through many hands, with a number of directors attached before it ended up with South African producer Anant Singh, who hired Hooper to direct. The script had also gone through a number of variations, with Hooper becoming involved in shaping the final version (the writing credits on the finished movie attribute it to Hooper along with Stephen David Brooks and producer Harry Alan Towers, who had previously held the rights, under his scriptwriting pseudonym David Welbeck). As with any short story, adaptation required elaboration, but the movie does manage to retain the overall narrative shape of King’s tale.

That tale is a little dumb – a series of odd coincidences causes a big laundry machine to become possessed by a demon which requires new sacrifices – but the adaptation adds an interesting wrinkle. The demon in the machine rewards those who supply sacrifices with wealth and social position. In fact, the elite in the small Maine town where the Blue Ribbon Laundry is the biggest business are all indebted to the possessed machine. This almost transforms King’s story into a sociopolitical satire, with the wealthy capitalist Bill Gartley (Robert Englund) literally squeezing blood from his workers to fuel his profits. But this theme isn’t expanded much beyond a suggestion.

The narrative follows the efforts of local police officer John Hunton (Ted Levine) to figure out why there are so many nasty accidents at the laundry. Hunton is tormented by guilt for having been responsible for his wife’s death in a car crash, but his bitterness and perpetual gastric problems (he chews antacids incessantly) never really play into the main narrative. Although he initially believes Gartley is just a lousy boss who ignores safety procedures, Hunton’s brother-in-law Mark Jackson (Daniel Matmor), who lives next door, is an overage hippy with an interest in the occult who gradually figures out what’s going on – something Hunton isn’t willing to believe until he encounters an old refrigerator which had been contaminated by the demon and seeks blood of its own (after suffocating a young boy, it tries to lop off Mark’s arm by slamming its door). When Hunton smashes it with a sledgehammer, it releases a powerful blast of unnatural energy, and he’s finally ready to consider the need for an exorcism.

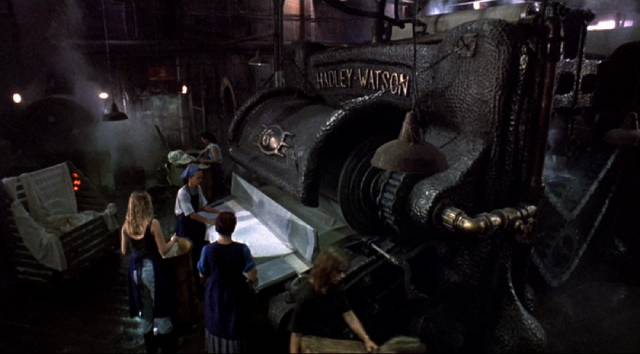

At 106 minutes, the film rambles and occasionally loses sight of the central thread – there’s a deadline for Hunton to sort out the deadly machine because Gartley’s niece Sherrey Ouelette (Vanessa Pike) is about to turn sixteen and the old man needs to sacrifice her to the demon to keep his petty empire running. And yet, like some of Hooper’s other lesser movies it does have strengths, particularly in the excellent production design by David Barkham and the Mangler itself, which was created by Hooper’s son William. The machine is impressive, a massive industrial behemoth spitting steam as its heavy chains turn big cogs which are always ready to drag unsuspecting employees into the works. The gore effects are equally well done, grotesquely crushing and folding those unfortunate enough to fall into the demon’s clutches.

The best parts of the movie take place in this industrial hell, which seems to embody the history of the industrial revolution and its centuries-long bloody consumption of workers’ flesh. Hooper takes his time to explore this terrible place, cinematographer Amnon Salomon’s atmospheric lighting and prowling camera providing an ominous, visceral menace which gives conviction to the supernatural threat. Robert Englund throws himself enthusiastically into the role of Bill Gartley, becoming a barely human extension of the machine which keeps him wealthy – his scarred face and the metal braces which hold him upright suggest that the price of his success has been a gradual transformation into a machine himself.

Englund pitches his performance to the overwrought tone of the film, turning in the best, and most appropriate, characterization. Levine and Matmor, on the other hand, flounder a bit as if not quite sure of what’s expected of them, with Levine in particular becoming mannered in a way which is increasingly distracting. Other performers manage to play things fairly straight, helping to ground the more outrageous elements of the story – Demetre Phillips as the foreman Stanner, Vera Blacker as the older employee Mrs. Frawley who meets a terrible fate, Pike as the intended sacrificial virgin.

The fact that The Mangler was shot in South Africa rather than Maine actually helps in some ways. With the need to disguise locations, Hooper is relieved of the necessity to create an authentic setting. This supports his instinct for the artificial theatricality which appealed to him. Even the suburban cul-de-sac in which Hunton lives seems like a studio set, echoing the studio exterior constructed for Eaten Alive.

The Mangler was a box office and critical failure, and it’s true that in basic storytelling terms it’s something of a mess. But watching it again on Arrow’s Blu-ray, years after I first saw it, I managed to see past the flaws and found much to enjoy, most of all Hooper’s visual skill and his disregard for the kind of naturalism which the mainstream tends to insist on – Hooper was more inclined towards the melodramatic excesses of grand guignol and, in his best work, shows no interest in tempering that inclination. Admittedly, The Mangler isn’t his best, but it does seem true to his creative instincts and I enjoyed it despite its flaws.

*

That can’t really be said of Spontaneous Combustion (1990), Hooper’s first feature after his troubled three-picture deal with Cannon Films (Lifeforce [1985], Invaders from Mars [1986], The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 [also 1986]). Although it reputedly had a higher budget than Chainsaw 2, this independent feature lacks the elaborate production design of the Cannon films and Levie Isaacks’ cinematography is serviceable but, for a Hooper movie, lacks much in the way of visual invention. The image on Code Red’s 2015 Blu-ray is quite murky, suggesting it probably came from a print rather than the original negative.

But apart from the impression of an impoverished production, the movie’s biggest weakness is its half-baked script – written by Howard Goldberg from Hooper’s own story. This is essentially like a cheap, unacknowledged knock-off of Stephen King’s Firestarter (filmed in 1984 by Mark L. Lester). Although it has its moments, mostly thanks to quirky lead Brad Dourif, the movie never establishes the rules of its pseudo-sci-fi premise and as it progresses it seems to become increasingly incoherent.

A lengthy prologue set in 1955 has a young couple volunteering for an experiment, ostensibly testing the efficacy of a new nuclear bomb shelter. Strapped in directly below a test explosion in the New Mexico desert, they survive seemingly unscathed. However, the real test is of an experimental “vaccine” against radiation – they were protected from the blast but not the bomb’s energy effects. And, although it was not supposed to be a part of the operation, the woman was pregnant. Although she gives birth to a seemingly healthy boy, she and her husband inexplicably burst into flame in the hospital room. The army types in charge want to dispose of the baby, but the head scientist wants to continue the experiment…

That baby grows up to be a teacher who knows nothing of his actual past and now suddenly finds himself possessing an increasingly uncontrollable power which causes other people to burst into flames. Although at first he gives off charges of static electricity, the power quickly begins operating at a distance – implying an element of pyrokinesis borrowed from Firestarter; some people burn some time after being in contact with him, others in his presence … it’s all pretty random.

As he tries to figure out what’s happening to him, he learns the truth about his birth and the shadowy agency which has actually been controlling his life, right down to his romantic relationships. In fact, his current girlfriend is part of the experiment and its the herbal pills she gives him for his headaches which seem to have accelerated the manifestation of his power, funnelled through her from the sinister scientist behind it all who sees the teacher as a new type of weapon.

There are occasional effective moments, and it’s nice to see Brad Dourif in a lead role, but Spontaneous Combustion looks ragged and impoverished, lacking the visual invention of Hooper’s better films. Pulpy and derivative, it nonetheless doesn’t shy away from a bleak and hopeless ending.

Comments