Budd Boetticher’s A Time for Dying (1969) from Indicator

If it looks like a duck, walks like a duck, but definitely doesn’t quack like a duck, is it still nonetheless a duck? I’m really not sure what to make of A Time for Dying (1969), the last movie for both writer-director Budd Boetticher and actor-producer Audie Murphy. It comprises a collection of familiar genre elements, but never quite coalesces into a predictable form. Boetticher, who got his start during World War Two, had eventually specialized in westerns, making some of the best released in the ’50s, when he had a long-running collaboration with Randolph Scott. He also made a fine gangster movie, The Rise and Fall of Legs Diamond (1960), which forms a kind of bridge between the classic Warner gangsters of the ’30s and The Godfather (1972), and had a lifelong passion for bullfighting which produced Bullfighter and the Lady (1951) and led to the protracted production of a documentary about the Mexican matador Arruza, ultimately released in 1972 after almost killing Boetticher.

Audie Murphy, who always disparaged his own abilities as an actor, became a minor star after the Second World War. Studios and producers happily cashed in on his name and reputation as the most decorated American soldier of the war. Quiet and boyish, he had racked up more kills and taken more prisoners in North Africa, Italy and Germany than any other individual. Strangely, despite that reputation, he had a very unthreatening screen presence – and a limited range; he had problems when he played the protagonist of John Huston’s adaptation of Stephen Crane’s The Red Badge of Courage (1951) because it was hard for him to convey fear and cowardice.

Boetticher and Murphy had worked together back in 1952 on The Cimarron Kid and had remained friends. When Boetticher ran into trouble in Mexico while making Arruza (at one point he went to jail for non-payment of debts, and at another time was committed to a psych ward for a while) Murphy helped him out financially. Murphy himself had a major gambling problem and ran into trouble with the mob, and in the late ’60s approached Boetticher about making a movie to clear some of his debts (reputedly, the movie was not supposed to be released so some backers could use it as a tax write-off). This project would be mutually beneficial – Boetticher hadn’t made a feature since Legs Diamond and was still some way off from completing his documentary, while Murphy’s acting career had petered out in a string of repetitive roles in undistinguished westerns. While Boetticher got another opportunity to direct, Murphy hoped to launch a new career as a producer.

There was very little money, but Boetticher managed to get help from people who were willing to work for reduced fees – including cameraman Lucien Ballard, who had just come off The Wild Bunch and True Grit (both also 1969) and would immediately go on to The Ballad of Cable Hogue (1970); Ballard had shot several of Boetticher’s movies in the ’50s, as well as Legs Diamond. Another way of keeping costs down was to tailor the script to young actors with little experience, who would be supported by experienced character actors who would appear in only one or two scenes. And, of course, the shooting schedule would be short.

This last point shows on screen in occasional accidents and errors which couldn’t be fixed by reshoots – although these accidents themselves actually add interesting details which give the movie a texture it might not have had if there had been more time and money available. In particular, there are moments involving horses which appear not to be fully trained – at one point, a white horse tethered to a hitching bar bucks during some action in the street and actually pulls down part of the shoddy facade; at another point, a horse falls during more action in the street, spilling lead actress Anne Randall who has to hurry out of the way. These moments add a note of contingency, a touch of realism.

The constraints of time and budget give the movie the feel of something shot for television (even Ballard’s photography occasionally has a hurried, slapdash quality), an impression reinforced by the young leads. And yet, made as it was towards the end of the ’60s, after six or seven years of the western being deconstructed by foreign (mainly Italian) directors who viewed the national American myth of the frontier with a critical eye, and more recent revisionist treatments of those same myths by American directors, particularly of course Sam Peckinpah, there’s a strange undercurrent to A Time for Dying which produces a disorienting dissonance between the apparent lightness and naivety of the surface and an almost indefinable sense of the unfamiliar.

That surface is made from fairly recognizable elements, assembled into an episodic picaresque coming-of-age narrative. Farm boy Cass Bunning (Richard Lapp) has set out into the world looking for adventure. He has a series of encounters which reflect the dangers as well as opportunities of the frontier. Having been trained in the use of guns by his father, he intends to make a name for himself (and maybe a fortune) by becoming a bounty hunter. But his encounters suggest that he’s not ready to take on that role – there’s a vast gap between skill and temperament. An alternative possibility arises when he meets an equally naive young woman, Nellie Winters (Anne Randall), who has arrived in the town of Silver City unaware that the job she has been promised is actually in a brothel.

Cass rescues her from that fate, though he’s not really prepared to settle down. The narrative has Cass and Nellie getting to know each other as he navigates potentially dangerous encounters with a number of men. All of which seems fairly familiar, the chief departure from standard westerns being the youth and inexperience of the protagonists. But even that reflects a trend in the genre which became more common into the ’70s with movies like Dick Richards’ The Culpepper Cattle Co., Robert Benton’s Bad Company and Mark Rydell’s The Cowboys (all 1972).

What throws A Time for Dying off kilter is its odd tonal qualities. At times it actually seems poorly made – Lapp’s performance in particular is frequently grating, his aww shucks naivety exaggerated to the point of mugging like a kid in a school play (this was apparently a problem for co-star Randall as well as Boetticher himself). Also exaggerated, although more finely tuned with comic self-awareness, is Victor Jury’s portrayal of the legendary Judge Roy Bean, a drunkard who has set himself up as an authority figure in his own small town named Vinegaroon (Jury is much better here than Paul Newman in John Huston’s The Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean [1972]).

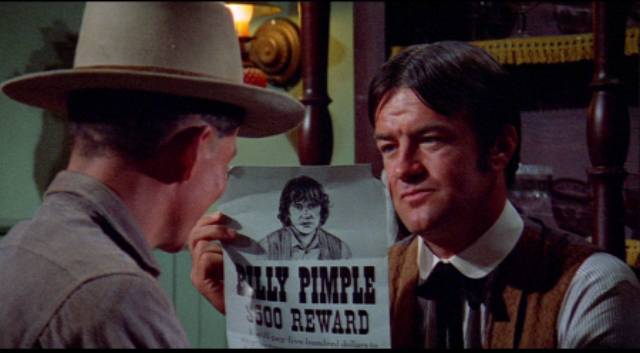

The movie alternates between strikingly effective moments and an almost amateurish quality. The opening sequence declares that it is not a reiteration of old school B westerns: a rattle snake eyes an oblivious rabbit as Cass watches. He raises his gun and in a disturbing close-up we see the snake’s head blown off, its body writhing in the throes of a violent death. A couple of years later Peckinpah would open his own Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid (1971) with gunmen entertaining themselves by shooting the heads off chickens, an unexpected display of animal violence usually forbidden in American movies. Moments after killing the snake, Cass encounters three men on horseback, one of whom asks what the shooting was about. When Cass says he killed a snake to save a rabbit, the unflatteringly named Billy Pimple (Robert Random) – his face is pockmarked with acne – asks why the snake’s life was worth less than the rabbit’s.

The encounter is freighted with a sense of menace – we later learn that Billy is an up-and-coming gunfighter who has been causing trouble in the town of Silver City – but the three men ride on, letting Cass go on his way. He arrives in the town to find the populace in the midst of a drunken revelry in the street, anticipating the imminent arrival of a new girl at Mamie’s cathouse. In the saloon, he learns who the man he met in the desert actually is and gives a display of his own gun skills. Sam the bartender (Ron Masak) and a pair of old geezers named Ed (Burt Mustin) and Seth (Peter Brocco) acknowledge them to be superior to Billy’s.

When the stage pulls in, the rowdy crowd terrify Nellie, who believes she’s come to be a waitress, not a prostitute, and Cass mounts his horse and rides through the crowd to scoop her up and carry her out of the town. He has no plan and they wander awkwardly until they reach a small cluster of buildings purporting to be the town of Vinegaroon, where they find a room for the night, with Cass sleeping in the corridor to prevent Nellie being disturbed. In the morning, some deputies arrive, disarm Cass and take the pair to see Judge Roy Bean, a garrulous drunkard who built the town and rules it with his own particular brand of “justice”.

When they arrive at the courthouse, they see the judge pass judgment on a young man named Sonny (Audie Murphy’s son Terry), accused of being a horse thief simply because he rode into town on a horse. Sentenced to death, the boy is dragged up a hill and strung up on a gallows. The casual brutality is barely registered by the gathered townsfolk, who are more interested in getting a drink between cases. Turning his attention to Cass and Nellie, the Judge accuses them of immoral behaviour and immediately makes it right by marrying them. The comic elements of the scene and Jury’s garrulous performance are at odds with the callous violence of the lynching; but rather than trivializing the violence, the clash imbues the comedy with menace – the ease with which these familiar frontier characters kill is deeply disturbing, undermining the genre trope of righteous violence.

And so, newly wed, the young pair start to get to know each other. Cass suggests that he should take her back to his father’s farm while he goes off to make his fortune by bringing in wanted outlaws. To prove the viability of his plan, he gives her a demonstration out in the desert, his shooting drawing the attention of another trio of riders. One of these men calls out for Cass to drop his guns, toss away his gunbelt, and drop his pants. Cass’s compliance doesn’t seem to bode well for his career plans, but the stranger turns out to be quite unthreatening.

In fact, this man offers Cass some helpful advice – if he’s going to do some target practice, he should do it up on high ground, not down here in a gully where he can’t see people approaching. He also points out that Cass’s sweaty palms are likely to cause problems if he has to draw quickly. He suggests that Cass may not be cut out to be a farmer, but he’s definitely not yet ready to be a gunslinger. When he is ready, though, he should come looking for this man and join his gang. And, by the way, his name is Jesse, and the other two men are his brother Frank and their friend Bob Ford. These are the men Cass has fantasized about hunting down for their rewards, but they seem like nice enough guys.

Jesse, a brief cameo which lasts only a few minutes, was Audie Murphy’s final role. While it bears no resemblance to the real Jesse James (a vicious criminal), Murphy displays genuine charm and screen presence before riding on his way. Soon after, another encounter doesn’t go so well. A gang of marauders (rather like the real James gang) “borrow” Nellie at gun-point while Cass has to watch helplessly. It’s an uncomfortable moment with a suggestion of gang rape – but it turns out that, for some reason, these men think her presence will provide cover as they ride into Silver City to rob the bank.

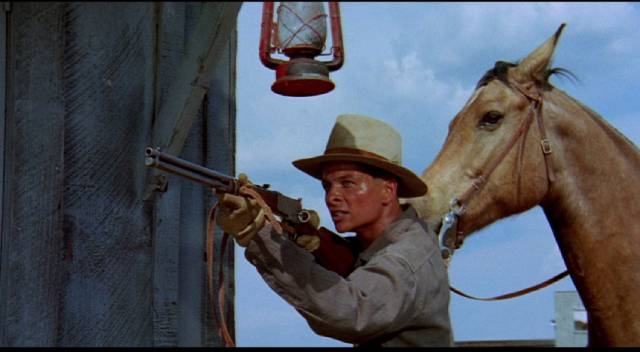

Pretending to be drunk, they cause chaos in the street, firing their guns and riding in circles while a couple of men attempt to break into the bank. Cass, who has followed them, starts shooting with his rifle, then sets fire to a bundle of cactus which he drags behind his horse to create a cloud of noxious smoke. A couple of the gang are killed, the rest fleeing, and Cass is honoured by the mayor, who gives him a reward for the dead men who are assumed to be members of the James gang.

Up to this point, A Time for Dying has been a picaresque tale with a few odd notes (the discordant “comic” brutality of Judge Roy Bean, the friendly encounter with the notorious Jesse James); it’s the story of a couple of naive kids who have yet to learn how insecure life is in this frontier world, a world lacking in the typical good-guy/bad-guy morality of the traditional Hollywood western; this is more like the amoral frontier of the Italian western, where good and bad blur into one another, and yet the characters remain recognizable American types, rather than the more mythic figures of the spaghetti western.

The naivety of the leads is pushed to extremes by Richard Lapp’s broad performance, an irritating display of grinning tics. Randall’s naivety is more touching, the inexperience of a young woman who doesn’t realize the dangers she faces in a world which values her only for the use to which her body can be put. Although Cass and Nellie might find mutual protection together, their chances of making it in this world are slight because of what he understands about “being a man”.

In its final few minutes, the film takes a turn into genuine, even shocking, darkness, shattering the western myth these characters believe they are a part of. The reward ceremony is interrupted as one of Billy Pimple’s buddies arrives to call Cass out. The young gunman has heard that Cass is gaining a reputation and he’s taking it personally; he wants a showdown. The classic finale would obviously have Cass standing up for himself, proving his value as the hero, and riding off into the sunset with his girl. But out in the dark street, facing a cold-blooded opponent for the first time, his skill is undermined by the weakness Jesse pointed out – his nervousness making his palms sweat profusely.

Billy draws; Cass draws … but Cass’s guns slide from his grip. Billy shoots and hits him twice. Nellie runs to him and cradles him in the street, getting blood all over her dress. Not satisfied with merely wounding Cass, Billy approaches and finishes him off with a rifle shot. The townsfolk gather round and Mamie and her prostitutes take Nellie in hand. In shock, she says that she doesn’t even know where Cass’s father lives, or even his name. Mamie says never mind, you can stay here as long as you need to – and so Nellie arrives at the fate she never understood and from which Cass had temporarily saved her, just one more brothel worker in this small frontier town where she’ll have to service the local drunks.

Billy rides off with his friends, knowing that his own end will be just as pointless and violent. And the stagecoach arrives with yet another young, fresh-faced girl looking for work at Mamie’s.

Boetticher’s laconic ’50s westerns, stripped to their narrative essentials, were a major factor in the rethinking of the genre – like Anthony Mann’s psychological westerns starring James Stewart – adding greater depth to what had largely been a formulaic collection of increasingly trite stock elements whose only purpose was to fill out kids’ matinees. Boetticher and Mann paved the way for Peckinpah and others who incorporated a sense of history into the mythology of the frontier and America’s self-aggrandizing belief in rugged individualism and Manifest Destiny, which in turn paved the way for the dismantling of that mythology in the spaghetti western.

But A Time for Dying seems displaced, with Boetticher (and Murphy) having been left behind by the rapid changes in part initiated by his own earlier work. This final movie is a disorienting hybrid which never manages to find a coherent balance between its roots in the cinematic past and its existence in a radically changed present. And yet this instability is itself what makes the film interesting and might have raised its profile in the history of the genre if a more capable actor had been cast in the lead – Boetticher had tried to get Peter Fonda, which could have made for a much stronger, more elegiac movie (something like Fonda’s own The Hired Hand, made just two years later).

Although obviously hampered by budgetary constraints and a consequent short shooting schedule, what gives A Time for Dying an unfinished, at times amateurish feel is largely Richard Lapp’s presence. The rest of the cast is actually quite good, with Jury and Bob Random even better than that. What seems most strange is that the movie gives the impression of a newcomer trying to find his way among familiar elements and new possibilities, rather than of a master drawing on many years of experience.

Indicator’s 2K scan of the original negative provides a vibrantly colourful image on the Blu-ray – for some reason presented in both 1.33:1 and 1.85:1 options (I watched the latter). Included on the disk are a commentary from C. Courtney Joyner and Henry Parke which fills in the details of the film’s strange production history; an appreciation by filmmaker Chris Petit who is fascinated by the film’s anomalous nature; and a discussion by Kim Newman of the ways in which Jesse James has been portrayed in the movies. This release unearths a fascinating footnote to the careers of two significant figures whose time had largely passed when they made the movie.

Comments