Rethinking Kane and Chain Saws

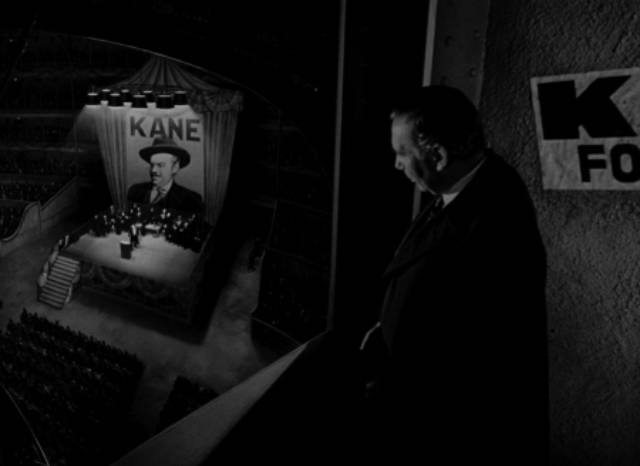

Citizen Kane (Orson Welles, 1941)

There are movies which I first got to see long after they had accrued formidable reputations. It’s not surprising that such prior knowledge affects the initial encounter – often to the detriment of the movie. A high bar has been set and, whether conscious or not, this creates a challenge which might be hard for any creative work to overcome. I can’t say exactly when I first saw Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane (1941), but I do know that when I finally got that opportunity (on television) I was well aware that this was “the greatest movie ever made”. It would have been sometime in the ’70s, so I was a bit younger than Welles when he made the movie. At that time, although my interest in film was already well-developed, my knowledge of cinema history and technique would have still been somewhat rudimentary, so I was probably unable to fully appreciate Citizen Kane’s innovations.

On that viewing and for years afterwards, Kane was something I could admire, but I can’t say I liked it in the sense that it fully engaged me on an emotional level. As my experience with Welles expanded, there were other movies which I liked much more – Touch of Evil (1958), The Trial (1962), Macbeth (1948), F for Fake (1973), and finally (again years after reading about it) Chimes at Midnight (1965), which I consider his greatest work. Still, I would occasionally revisit Kane, always with a bit more knowledge – I had read Pauline Kael’s Raising Kane in 1972, which had given me a negative impression of Welles; but then there was Robert L. Carringer’s 1985 book about the production, which offered a more nuanced corrective in its detailed account of Welles’ collaboration with the key figures who helped him create the film; and around the same time, Barbara Leaming’s biography of Welles, which fleshed him out as a character, though if I remember correctly it also subscribed to some degree to the common perception that his subsequent career had been a kind of failure because of his stubborn insistence on going his own way instead of accommodating himself to the mainstream movie industry; and finally, in the ’90s, there was Peter Bogdanovich’s hefty collection of career-spanning interviews, This is Orson Welles, and my discovery of Jonathan Rosenbaum who had written extensively about Welles, culminating in his 2007 collection Discovering Orson Welles.

All that reading, along with watching and re-watching Welles’ movies and gradually forming my own opinions about his work, somehow never quite cracked my original reticence about Kane. While my admiration increased the more I learned, I still retained a detached distance. Until, for some reason, my recent viewing of Criterion’s 4K restoration. Surely it can’t just be the visual quality that shifted me, and yet I felt myself so completely immersed in the film that every changing emotional note resonated in a way it never had before. Welles’ energy and enthusiasm as a performer, seemingly so relaxed as he moves from youthful brio to aging alienation, permeates every frame – ironically, the further we get into reporter Thompson’s investigation, the more uncertain our understanding of the character becomes … right up to the final reveal of “Rosebud” which reveals nothing at all. Because the movie begins with Rosebud and ends with Rosebud, and Rosebud provides the impetus for the investigation of Kane’s life, the weight we place on it as viewers becomes Welles’ final joke on the audience.

Made as it was at the height of Hollywood’s (and society’s) fascination with psychoanalysis, the temptation is to read the symbol as a literal key to Kane’s life – that decades’ long pursuit of power which devolves into the obsessive acquisition of material possessions is driven by the deep sense of dispossession and abandonment he’s carried with him since being torn from his childhood home and mother to be raised by a bank. This reductionism belies the film’s larger satirical treatment of the awful consequences of America’s conflation of politics and money, of money as the root and meaning of power, which becomes its own purpose, with no other end than growth and acquisition for its own sake. Despite Welles’ dominating performance, it’s clear that no individual can maintain a clear personal identity in this socio-politico-economic maelstrom. If that final gasp of “Rosebud” means anything, perhaps it’s simply a dying recognition that there was a time when things seemed simple and that simplicity might have been more desirable than the futile complexity of the life wealth had imposed on him.

Watching Citizen Kane again, I found Welles’ enthusiasm infectious. Every frame seems to stretch what was deemed possible by a production system which had become entrenched. The same reputation which had provoked RKO to offer the 26-year-old Welles a remarkable, indeed unprecedented, contract – no interference, complete creative freedom, final cut – was what attracted some of the best talent in the business to join him; award-winning cinematographer Gregg Toland saw in Welles an opportunity to experiment, to risk failure in ways few studio directors would be willing to allow. With no prior experience in film (but already years of experience in theatre and radio), Welles wasn’t bound by the rules.

As noted in Criterion’s disk extras, the visual style of Kane is heavily influenced by Welles’ theatre experience; the prominent use of low angles is analogous to the way an audience experiences the stage, and that in turn necessitated the unusual addition to ceilings on the sets, which in turn gives the film’s imagery a sense of realism rare in studio productions. As a result there’s a heft to Kane which serves it well not merely in a dramatic sense, but also thematically; the materialism being criticized is given a material presence on screen.

Perhaps less noticeable but just as important, Welles’ radio experience had a big impact on the film’s use of sound. In addition to the prevalence of overlapping dialogue, there’s a layering and suturing across scene transitions which gives the film an energy and pace which avoids the kind of ponderousness too often found in decade-spanning Hollywood epics. But as with Kane himself, this energy gradually becomes exhausted; in the later scenes as he and Susan Alexander (Dorothy Comingore) rattle around in the vast, echoing hall of the unfinished castle, what had begun as a larger-than-life explosion of vitality has become an enervated trickle of boredom and bitterness – a lifetime of activity has ended in a void which we can both see and hear in a way which still seems audacious.

Did Welles try to hog the credit for all these innovations? That was Kael’s suggestion, particularly with regard to the script credited to Welles and Herman J. Mankiewicz. And yet in interview clips included in the various disk extras, he seems to acknowledge just how much he drew on the experience and talents of his collaborators, creative forces themselves who had seized on this opportunity to stretch their own technical abilities. Welles even shared his director title card with Toland, an unusual public acknowledgement of the cinematographer’s contribution. Whatever the intricacies of the collaborative process and the relative contributions of everyone involved, it’s undeniable that this remarkable opportunity to break out of established industry constraints existed only because of Welles’ unique position … a position which would almost immediately become compromised with his second film, The Magnificent Ambersons (1942), which, despite the recognized artistic achievent of Citizen Kane, the studio took away from Welles and released in a butchered form.

Criterion’s new release (a dual-format 4K UHD/Blu-ray combo) looks terrific, the image having excellent contrast and detail, with three commentaries (two from 2002 – Peter Bogdanovich and Roger Ebert – and a new one with Jonathan Rosenbaum and James Naremore), and no less than two supplementary Blu-rays stacked with extras: a feature-length BBC documentary from 1991, plus numerous new and archival video essays and interviews covering every aspect of the production. There are also several Mercury Theatre radio plays and Welles’ early short film The Hearts of Age (1934), and a fine essay from critic Bilge Ebiri in the booklet.

The package surrounds the feature with plenty of context and interpretation, but what surprised me the most, after all these years and many viewings, was how much the movie resonated with me this time. It’s as if, after decades, I have finally caught up with it.

*

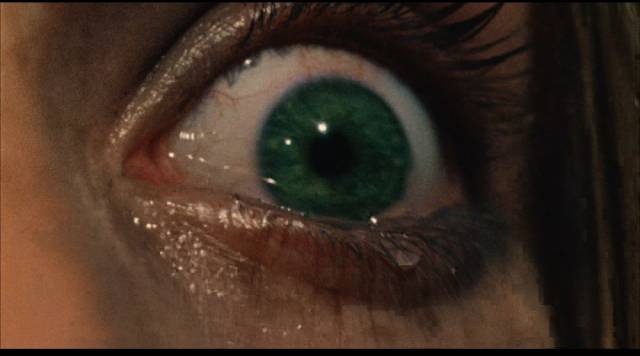

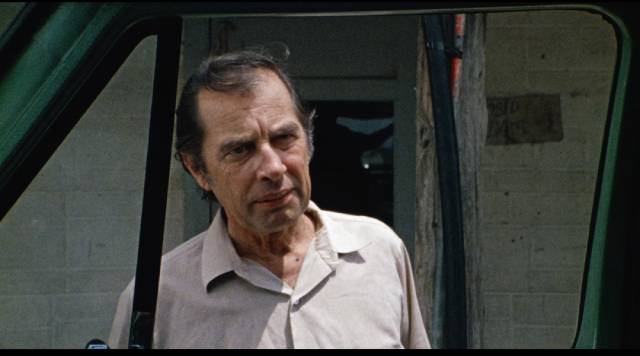

The Texas Chain Saw Massacre

(Tobe Hooper, 1974)

Although in no way equal in most senses, I had a similar experience with Tobe Hooper’s The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974). Again, I can’t recall exactly when I first saw it, but by then I’d heard that it was one of the most terrifying movies ever made. So I had high expectations – after all, it was sharing cinematic space with George Romero’s Night of the Living Dead (1968). I was very disappointed. For a movie with Chain Saw’s reputation, it was surprisingly bloodless – the actual chain saw attacks were merely suggested; the only blood shown (apart from Leatherface’s unsanitary apron) comes from the cuts Sally (Marilyn Burns) gets when she jumps through a window. Actually, she jumps twice which seemed to me to stretch credibility, if one can use “credible” in the context of rural cannibals cutting up unwary travellers with a chain saw.

On that first encounter (and occasional subsequent viewings), I couldn’t get past how restrained it was for a horror movie and a general impression, particularly in the early scenes, that it was just a low-budget regional effort like so many others. But two things did stand out – the moment when Leatherface (Gunnar Hansen) scoops up Pam (Teri McMinn) and hangs her on a meat hook, which itself is not graphic, but the idea is shockingly brutal; and the climactic dinner sequence in which the family try to help the living mummy Grandfather (John Dugan) to kill Sally with the small sledgehammer which the old man can no longer hold. Here the movie achieves a distinctive level of nightmarish comedy; displaced by newer technologies of slaughter, the family is trying to cling to a lost sense of worth rooted in a proficiency in killing – with no more access to cows, they’ve turned to more vulnerable human beings for their meat.

Having no prior expectations, I liked Hooper’s follow-up much better. I also saw in the sheer theatricality of Eaten Alive (1976) a clue to what I thought had worked best in Chain Saw – that dinner scene. The mixture of horror and absurdist comedy in Eaten Alive seemed to energize Hooper; the exaggerations of the studio sets removed the story from the more naturalistic style of Chain Saw, creating space for the idiosyncrasies of Neville Brand and William Finley, whose performances nudge the film towards nightmare surrealism. It appeared that this stylized approach to horror was more to Hooper’s taste – something I saw confirmed in the production design and performances of The Funhouse (1981), Lifeforce (1985), Invaders From Mars and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 (both 1986).

And yet … watching the original Texas Chain Saw Massacre again the other day on Dark Sky Films’ 40th anniversary Blu-ray, I once again experienced that strange sense of seeing a familiar film for the first time. Could it just be because the 4K transfer revealed how impressive Daniel Pearl’s cinematography really is? The movie looks remarkably good for a now five-decade old 16mm production, with vibrant colour and a lot of detail. But what I found myself noticing clearly was the skill and intelligence with which Hooper used both camera and editing.

The risk with very low budget productions is that the filmmaker will shoot in a perfunctory style just to get the scenes in the can as quickly and efficiently as possible. Hooper’s choices, however, look for the expressive possibilities of the moment; the framing and the almost continual movement of the camera in concert with the blocking of the actors produce a sense of unease from the start. The audience is primed to expect something because the camera is constantly probing and exploring, and it’s this air of unease which leads to viewers thinking they must have seen something which in fact has only been suggested. Hooper fools the collective imagination into conjuring up the horror he isn’t actually showing.

I still think that Hooper didn’t quite find the right balance between the apparent naturalism and a heightened sense of theatricality. The cannibal family edge very close to caricature, occasionally crossing that line, while Sally, her wheelchair-bound brother Franklin (Paul A. Partain) and their friends remain rather generic horror-movie fodder, the kind of bickering group which would shortly turn up as victims in countless slasher movies. What rose in my estimation this time round was Hooper’s control of the narrative apparatus, the combination of image and sound which transcends the limitations of performance.

I’ve seen and re-seen so many movies over many decades that it comes as a surprise that I can still find something new in what has long-since become familiar and perhaps even a little stale. This experience of both Citizen Kane and The Texas Chain Saw Massacre in the same week has a revitalizing effect. I have to wonder what other movies might be worth looking at again.

Comments