Winter viewing 1: Vinegar Syndrome

Things have been piling up as usual, so here’s a quick glimpse of what’s been screening here over the past three months. There’s a lot of “trash” in here, and I do feel somewhat self-conscious about that. But I suppose I just need to own up to the fact that my taste, although pretty broad, has been leaning in recent years towards exploitation and B-movies, predominantly from the 1960s through the ’80s. I have a friend who teaches film at university who tells me that he finally came to terms with the fact that what he enjoys most is low budget genre movies from the ’50s, and outside of work, those are what he watches. I haven’t quite reached that level of acceptance, even though I spend way more on releases from Vinegar Syndrome, Severin and Arrow than I do on Criterion.

Vinegar Syndrome

Beware: Children at Play (Mik Cribben, 1989)

Here’s a good example of my ambivalence. Mike Cribben’s Beware: Children at Play (1989), the sole directing credit of a technician with multiple sound and camera department credits, is a derivative low-budget movie from New Jersey which plods through what is essentially a riff on Children of the Corn. A bit amateurish, sluggishly paced, it builds towards a surprisingly transgressive final act which we would be unlikely to see in a more recent production.

In a prologue, a man and his young son enjoy a camping trip in remote woods. As they fish and play, the father endlessly quotes from classic literature (particularly the Anglo-Saxon epic about Beowulf and Grendel). When the dad gets caught in a bear trap, the boy watches for days as he slowly goes mad and dies. Ten years later, kids start disappearing from a small town. The locals become increasingly angry and hostile to the sheriff, whose own kids are among the missing, and they are riled up into a murderous mob by a religious fanatic.

The kids aren’t dead, though. They’ve been taken and indoctrinated by the now-teenaged boy who has survived alone in the woods, identifying more with Grendel than the hero Beowulf. He has transformed them into a wild, Lord of the Flies-like tribe of cannibals who now prey on any adults who wander into their realm. As the townsfolk prepare to hunt the kids down (convinced by the fanatic that they are no longer their children, but rather demonic monsters), we get the disturbing sight not only of the kids chowing down on unfortunate victims, but also watching their leader rape the captured mother of one of the tribe’s newest members.

The sheriff, trying to stay ahead of the mob, recognizes that all these kids are suffering from severe trauma and in need of help, but the townsfolk arrive and proceed in their righteous anger to slaughter them all with guns, knives and whatever else they have at hand. It’s all very dark and graphic, and more disturbing than the more mainstream Children of the Corn. And being an ’80s movie, it ends on a cynical, downbeat note.

Despite its limitations – technical and creative – Beware: Children at Play sticks with the implications of its premise and follows them to a logical conclusion without flinching. What more can you ask of a cheap horror movie?

Creature (William Malone, 1985)

My favourite William Malone movie is his underrated update of William Castle’s House on Haunted Hill (1999), but his second feature, Creature (1985), is a pretty good example of a low-budget rip-off of a big studio hit – in this case, and very blatantly, Ridley Scott’s Alien (1979). There also seems to be a good dose of Norman J. Warren’s Inseminoid (1981), itself a blatant Alien rip-off. Made on a small budget, Creature has some decent miniatures and a passable man-in-a-suit monster. The cast is mostly competent, with the added spice of Klaus Kinski in a supporting role.

The story – presented in two versions on Vinegar Syndrome’s disk, the theatrical Creature and the slightly longer director’s cut The Titan Find – has a crew going to investigate the disappearance of a previous expedition to Jupiter’s moon Titan. The earlier team had discovered an alien life form which wiped them out, and which now preys on the rescue team. Kinski is the sole survivor of a rival German crew, who knows what’s going on as the creature picks people off one by one (somehow also able to reanimate the dead). Cheesy and unoriginal, Creature displays enthusiasm and occasional ingenuity on the filmmakers’ part, sitting comfortably near the top of the post-Alien heap.

Curfew (Gary Winick, 1989)

Gary Winick had a varied career as a producer – Richard Linklater’s Tape (2001), Peter Hedges’ Pieces of April (2003) and Wim Wenders’ Land of Plenty (2004) among others – and occasional director – the coming-of-age comedy Tadpole (2002), a charming adaptation of E.B. White’s Charlotte’s Web (2006). His directorial debut, Curfew (1989), is competent, but rarely rises above that level. A couple of psychotic brothers, in prison for murder, break out and return to the small town site of the crime to wreak revenge on the judge, jury and prosecutor who put them away. It all takes place over one night, moving from house to house as the bodies slowly pile up. The echoes of Halloween (1978) are reinforced by the presence of Kyle Richards, Lindsey in Carpenter’s movie, as teen heroine Stephanie, the daughter of prosecutor Walter Davenport (Frank Miller).

As the movie goes through the motions with occasional moments of suspense, its main interest is in the two brothers, the dominant Ray (Wendell Wellman) and dumber, more manipulable Bob (John Putch). Unlike the almost abstract bogeyman in Halloween, they’re a sick and twisted pair trapped in a mutual madness which spurs them to increasing levels of violence while ultimately making them vulnerable to the smarter, more self-possessed girl seemingly destined to be their final victim.

Dead Heat (Mark Goldblatt, 1988)

Mark Goldblatt is an editor who began his career working for Roger Corman (his first editing credit was Joe Dante’s Piranha [1978]) and went on through a string of notable genre movies on his way to specializing in big-budget sci-fi and action features (Terminator 2: Judgment Day [1991], True Lies [1994], Starship Troopers [1997]). He tried his hand at directing just a couple of times, between cutting Penny Marshall’s Jumpin’ Jack Flash (1986) and Clive Barker’s Nightbreed (1990). His second feature was the first version of The Punisher (1989)[1], starring Dolph Lundgren, but the first was a horror-sci-fi-comedy called Dead Heat (1988), a fantasy variation on familiar cop-buddy tropes.

Although I generally like movies which mix genres, Dead Heat (for me at least – it has a cult fan base) never quite seems to find a tone that makes all the elements fit together comfortably. The wise-cracking cop buddies (Treat Williams and Joe Piscopo) are occasionally at odds with some graphic violence, while the rules of the sci-fi/horror elements are never laid out clearly and seem to change from moment to moment.

After a very destructive shoot-out at a jewel store robbery, our cop buddies discover that the almost indestructible thieves were actually a couple or reanimated corpses. Their investigation takes them to a big pharmaceutical company where they uncover the machine which revives the dead (shades of Edward L. Cahn’s Creature with the Atom Brain). Whoever is behind this kills one of the cops (Williams), but he’s revived by the machine and discovers that he has only twelve hours to solve the case before he’ll be permanently dead.

As he quickly decays, the investigation eventually uncovers a plan by the supposedly dead CEO of the company (a brief cameo by Vincent Price) to sell immortality to rich people. Given the need for secrecy, it seems odd that he’d risk it all by reviving thugs to raid jewellery stores in broad daylight – but that’s one of those odd genre traditions, the use of paradigm-changing scientific discoveries for mundane criminal purposes.

Production values are decent, and Goldblatt puts his editing experience to good use for the action sequences, but as in most cop-buddy movies a lot rests on the chemistry between the stars. It’ll be a matter of personal taste whether that works here, but personally I didn’t get anything from Saturday Night Live alum Piscopo, who exhibits no on-screen charm for the always-reliable Williams to work off. Price has little to do, but Darren McGavin as the smarmy coroner obviously relishes playing the villain. The highlight of the movie is a scene in a Chinese restaurant where the revivifying technology animates all the food in a rousing practical-effects extravaganza as the heroes are attacked by barbecued ducks and pig heads.

Deadline (Mario Azzopardi, 1980)

Maltese-Canadian director Mario Azzopardi has had a long, prolific career in television for the past forty years, but he started with this interesting tax shelter horror movie. Deadline (aka Anatomy of Horror, 1980) is the story of a writer who has had great commercial success with pulp horror novels but deep down wants to be taken seriously. In the opening section, he gets some harsh criticism from students in a university literature class who attack him for the harm his violent fiction does to society, particularly through all the gory movie adaptations. As he tries to defend himself (he’s just reflecting society as it is), we are shown bloody scenes from those adaptations, a string of trashy, exploitative deaths which graphically undermine his pretensions.

The stress of this conflict between his self-image and the reality of his work is eating away at him and as he struggles with his new book, a quest to find the ultimate, meaningful horror, the line between imagination and reality begins to blur and his fictional creations seem to bleed into his life, fracturing his marriage and resulting in a family tragedy.

What the movie is trying to say about creativity, commercialism, art and selling out isn’t exactly clear – it wants to entertain an audience looking for shocks, yet it appears to be condemning violence-as-entertainment. Of course, the exploitation of violence (and sex) in popular culture which disguises what it offers behind a censorious tone of condemnation is as old as storytelling itself. Almost as old is the idea of the artist who gets lost in his own creations. Deadline has a serious tone, but little real depth; it uses these themes but doesn’t really explore them, satisfied to remain pulp entertainment offering the audience some suspense and a few shocks.

Deadly Games: Dial Code Santa Claus

(René Manzor, 1989)

France has a spotty history with fantasy and horror movies (odd, considering what a big part Georges Méliès played in the origins of cinema), but when the French do take a stab at the genre, they occasionally come up with something interesting (Georges Franju’s Eyes Without a Face [1960], Marc Caro and Jean-Pierre Jeunet’s City of Lost Children [1995], and the films of Jean Rollin). René Manzor’s 3615 code Père Noël (aka Deadly Games, aka Game Over, 1989) is a real oddity, a kind of proto-Home Alone/Krampus mash-up which seems like a kids’ movie, but is surprisingly dark.

Thomas (Alain Musy) is a precocious boy who lives in a huge mansion with his divorced mother (Brigitte Fossey, herself formerly star of a dark film about children, Rene Clement’s Forbidden Games [1952]) and his ailing grandfather (Louis Ducreux). The house is a wonderland of corridors and secret rooms and he spends his time setting booby traps and playing tricks on the adults and family dog. It’s Christmas Eve and Mom is dealing with last-minute problems at work – which includes having to fire the creepy store Santa (Patrick Floersheim). Obviously psychotic, Santa heads to his former boss’s home and launches an assault on Thomas, who believes he’s a very malevolent real Santa.

Using all his skills, Thomas plays a strong defense as Santa kills peripheral characters and threatens grandpa. The setting gives the film a fairy tale tone, but it’s more authentic Brothers Grimm than sanitized Disney, with blood, pain and death facing the boy who has been sheltered by wealth and is used to being in charge of his own domain.

Don’t Answer the Phone! (Robert Hammer, 1979)

In the post-Halloween decade, as the slasher genre quickly rose and then slowly declined in popularity, there was a sleazier, more disturbing sub-genre which didn’t attain the same level of popularity but probably scarred audience members more deeply. Related to the slasher in that they offered a string of brutal murders as a supposed source of entertainment, they differed in their focus on the perpetrator rather than the victims. There was no mystery about who was doing the killing because we got to spend our time with these sick guys, getting to know them and the twisted roots of their homicidal mania. There’s a sweaty unpleasantness about these movies which makes them harder to shake off than Halloween and its offspring – but the pathology also makes them more interesting.

This strain of horror can trace its roots back to Psycho, but by the ’80s filmmakers were pushing things far beyond Hitchcock’s elegant character study. There was Joe Spinnell sobbing while he scalped his victims in William Lustig’s Maniac (1980) and doing unsavoury things to his “customers” in Frank Avianca et al.’s The Undertaker (1988), Robert Brian Wilson’s orphan going crazy in a Santa suit in Charles E. Sellier Jr’s Silent Night, Deadly Night (1984) and Cameron Mitchell’s apartment block caretaker in Dennis Donnelly’s The Toolbox Murders (1978) among others.

One of the sweatiest and most unsavoury exemplars was Nicholas Worth as traumatized Vietnam vet Kirk Smith in Robert Hammer’s Don’t Answer the Phone! (1979). He uses his job as a photographer (he’ll do legitimate fashion shoots as well as porn) to lure women to his studio where he loses control and gets sexual release from killing them. In between murders, he phones a radio psychologist and confesses to his crimes, eventually killing while on-air. The atmosphere is decidedly rank, but one-shot director Hammer gives it a kind of authenticity, which in turn is reinforced by Worth’s uncomfortably committed performance. A busy character actor with a four-decade career, Worth seizes this opportunity to play the lead and immerses himself without restraint in Smith’s sickness.

Ebola Syndrome (Herman Yau, 1996)

The tonal qualities of Asian cinema can be quite disorienting, as low comedy mixes with extreme violence and uncomfortable attitudes towards sex. In Herman Yau’s Ebola Syndrome (1996), when his boss catches him screwing his wife, Kai (the great Anthony Wong) brutally kills the man and his wife and flees Hong Kong. Years later, he’s working in a restaurant in South Africa, continuing his anti-social ways. When his boss takes him on a trip into the back country in search of cheap meat, they find a village beset by plague. Kai, not wanting to miss an opportunity, rapes a woman delirious from disease and contracts Ebola himself. However, he doesn’t get sick; he’s a carrier, who begins to spread the disease to the restaurant’s customers.

One of those customers turns out to be the grown-up daughter of the couple he originally killed; she recognizes him from her traumatic memories of seeing her parents murdered and tries reporting him to the police. On the run again, Kai returns to Hong Kong and spreads the plague in his old home town. There’s a lot of gushing bodily fluids and spewing vomit on the way to a final bloody showdown – which no doubt accounts for the movie’s cult status. But the jokey tone keeps it from having the kind of disturbing impact delivered by Category III classics like Yau’s own Untold Story (1993) and Billy Tang’s Run and Kill (1993), which plunge completely into nihilistic horror.

in Paul Leder’s The Eleventh Commandment (1987)

The Eleventh Commandment (Paul Leder, 1987)

Exploitation filmmaker Paul Leder is perhaps best known for I Dismember Mama (1972) and the absurd Ape (1976) – in 3D! The Eleventh Commandment (1986) is an interesting variation on slasher and psycho killer tropes, which seems almost quaintly old-fashioned, like a ’60s soap opera into which a deranged killer wandered by mistake. The plot revolves around the machinations of various family members over control of a profitable business. Ruthless Charles Knight (Bewitched’s Dick Sargent) has killed his brother and his wife and is now vying for control with sister-in-law Joanne (Marilyn Hassett). The biggest obstacle to his plans is nephew Robert (Bernard White), but he seems to have that under control – Robert, who believes he’s a priest and insists that he saw Charles kill his mother and father, has been confined to a mental institution whose staff are in Charles’s pay. He’s regularly abused by the staff and subjected to excessive electroshock therapy.

One day, Robert makes a bloody escape and heads home – as much to protect his favourite niece Deborah (Lauren Woodland) as to get revenge. Having killed the family chauffeur, he picks Deborah up at school and drives her around, killing some more people along the way. The movie’s focus on the childlike relationship between Robert and Deborah provides an odd counterpoint to the increasing body count. The final stretch, back at the family mansion, tips over into black comedy – it’s structured like a classic bedroom farce, but the sexual games are replaced with bloody murders. Leder might not have been much of a stylist, but his script (adapted from a story by William Norton) is an oddly engaging character study laced with violence.

Forgotten Gialli Volume 4

Vinegar Syndrome’s latest collection of less well-known gialli highlights the sleazier depths to which the genre descended as it fought off exhaustion and over-familiarity in its second decade. These three movies border on the pornographic at times, though each still manages to cling to the genre’s central appeal as a vehicle for violence borne out of psychological derangement. There’s a high level of kink in Enzo Milioni’s The Sister of Ursula (1978), which makes great use of a visually stunning location on Italy’s Amalfi Coast as well as an interesting cast (Barbara Magnolfi, Stefania D’Amario, Marc Porel), and Stelvio Massi’s Arabella: Black Angel (1989), in which the nymphomaniac wife (Toni Cansino) of a wheelchair-bound novelist (Francesco Casale) becomes the subject of his latest book as she sinks into a kinky sexual underworld, followed by a string of perverse murders.

in Camillo Teti’s The Killer is Still Among Us (1986)

Camillo Teti’s The Killer is Still Among Us (1986) is quite different. Based on an on-going (and unsolved) case in which Florence was terrorized by a series of brutal murders, it bears a strong resemblance to the Zodiac case in California. The killer (or killers) preys on couples who park in remote places for a bit of secluded sex. A student working on a thesis about an earlier case which strongly resembles the new murders investigates despite being warned off by both the authorities and, it seems, the killer himself, who phones her with threats. Like the Zodiac case (and David Fincher’s film about it), Teti’s movie remains unresolved, which itself distinguishes it from the typical giallo.

Graduation Day (Herb Freed, 1981)

Herb Freed’s Graduation Day (1981) is a fairly standard slasher, as indicated by the generic title. Anne (Patch Mackenzie) takes time off from the navy to return home after her younger sister Laura (Ruth Anne Llorens) drops dead at the finish line during a high school track meet. As the rest of her class prepares for grad, someone in a fencing mask begins to pick off the other members of the track team. As the bodies pile up, Anne tries to get to the bottom of it all, dealing with bitchy high-schoolers, a randy principal (Michael Pataki) and the team coach (Christopher George), who drives the kids to their limit with his obsession to win. The main attraction here is the cast, particularly Pataki and George, with supporting roles going to a young Linnea Quigley and Vanna White just a few years before she attained fame turning tiles on Wheel of Fortune.

Killing Birds (Claudio Lattanzi, 1987)

The tendency of distributors to do whatever they can to cash in on previous successes leads to baffling oddities like trying to sell Claudio Lattanzi’s Killing Birds (1987) as Zombie 5. There’s no connection between this and George Romero’s Dawn of the Dead (1978) or Lucio Fulci’s Zombie (1979) or the equally disconnected Zombie 3 (Lucio Fulci/Bruno Mattei, 1988) and Zombie 4 (Claudio Fragasso, 1989). What there is is a petty random series of events, beginning with a Vietnam vet returning to his bayou home to find his wife and friend in bed together. After killing them, a tethered falcon on the veranda attacks him and pecks out his eyes.

An indeterminate number of years later, a group of college students mount an expedition in search of a supposedly extinct woodpecker. Their first stop is the home of blind expert Dr. Brown (a slumming Robert Vaughn), who gives them a frosty reception. He warns them against their search – because it’ll take them to his abandoned bayou home where his family “disappeared” years ago. Undeterred, the students make it to the derelict house where they encounter bird attacks, apparitions and inexplicable zombies. None of it makes a lick of sense, but there are a few atmospheric moments and a bit of suspense as the students fall one by one to possibly supernatural forces.

Master of the World (Alberto Cavallone, 1983)

I’m not a huge fan of caveman epics, but given the choice I prefer outright fantasies like Don Chaffey’s One Million Years B.C. (1966) or Val Guest’s When Dinosaurs Ruled the Earth (1970). There’s also a sub-set which blends cavemen with the sword-and-sorcery genre, like Umberto Lenzi’s Ironmaster (1983). But after Jean-Jacques Annaud’s Quest for Fire (1981), there were a few attempts to present anthropologically “authentic” depictions of prehistoric life – all as silly as Annaud’s overrated movie. Although scripted by John Sayles, Michael Chapman’s The Clan of the Cave Bear (1986) was obviously doomed with the casting of Daryl Hannah as the heroine, but at least that had camp value. Alberto Cavallone’s Master of the World (1983) is unrelentingly dull as it presents grunting tribes pointlessly attacking one another at interminable length. Brutal, with bursts of graphic gore (to gain your enemy’s strength, you might want to eat his brains), it seems to have no actual point, with neither documentary authenticity nor cheesy entertainment value.

Memorial Valley Massacre (Robert C. Hughes, 1988)

Yet another awkward body-count movie (what keeps me coming back?), Robert C. Hughes’ Memorial Valley Massacre (1988) has crass developer Sangster (Cameron Mitchell, who during the ’80s was phoning it in for as many as ten movies a year) re-opening the Memorial Valley campground despite dire warnings from ranger George Webster (John Kerry) and Sangster’s own son David (Mark Mears), who’s concerned about preserving the area against exploitation. Meanwhile, as an assorted bunch roll in for the long weekend, a young guy living the caveman life begins killing off the obnoxious litterbugs and dirt bikers who are encroaching on his territory. Sympathy actually lies with the killer in this one since the campers are a thoroughly obnoxious bunch.

New York Ninja (John Liu & Kurtis M. Spieler, 1984/2021)

I really wanted to like New York Ninja because of the production’s interesting back story. Writer-director-star John Liu shot his cheap martial arts/crime movie on the streets of New York in 1984, but abandoned the project and went back to Asia. Decades later, the uncut reels resurfaced (but without any of the sound rolls) and Vinegar Syndrome financed the completion of the movie. This involved not simply editing the material, but figuring out what the story and dialogue were because no script was available. Kurtis M. Spieler had to write a new script and edit based on what he gleaned from the picture elements.

I guess I had been hoping that the basis for all this would be a gritty action movie serving as the foundation for a genre deconstruction … but it’s obvious that Liu was playing a lot of his original, uncompleted movie for comedy. Spieler performed a remarkable salvage job, but in the end I couldn’t muster a great deal of interest in the results. It’s no doubt unfair to judge the movie by my own inflated expectations and perhaps when I re-watch it in time I’ll be able to appreciate it on its own terms.

Pandemonium (Alfred Sole, 1982)

Alfred Sole is hard to pin down. From the mid-’90s, he’s had a prolific career as a production designer, but back in the ’70s and early ’80s he directed several features in wildly different styles. His best – and best-known – is Communion aka Alice, Sweet Alice (1976), which he followed a few years later with Tanya’s Island (1980), something like an homage to Walerian Borowczyk’s The Beast (1975). Switching gears again, he made Pandemonium aka Thursday the 12th (1982), a very hit-or-miss parody of slasher movies. With brief appearances from the likes of Donald O’Connor, Eileen Brennan, Sydney Lassick, Tab Hunter, Eve Arden, Judge Reinhold and Phil Hartman, it has the feel of a sketch comedy show. That’s amplified by the presence of Tommy Smothers and Paul Reubens as an inexplicable pair of Canadian Mounties investigating the deaths at a school for cheerleaders run by Bambi (Candice Azzara) who herself was shunned some years ago by a group of cheerleaders who were killed by being skewered with a javelin. Among the students at the school is Candy (Carol Kane), who has Carrie-like powers. The Airplane-like approach to the slasher genre guarantees at least a few amusing moments, and it’s interesting that this came so early in the bloody flood of body-count movies.

The Severed Arm (Thomas S. Alderman, 1973)

While Halloween launched the slasher movie as a profitable genre, there were precursors – like Bob Clark’s Black Christmas (1974) and this interesting little oddity. Thomas Alderman’s The Severed Arm (1973) begins with Dr. Jeff Ashton (David G. Cannon) receiving a package containing a severed arm. Instead of calling the police, he runs to his buddy Ray (John Crawford). In a flashback, we learn that they and several other friends went cave exploring five years earlier and found themselves trapped underground. After a couple of weeks, getting hungry, they drew lots and the loser was supposed to sacrifice his arm to feed everyone. In the event, he wasn’t willing, but the others cut his arm off anyway … just moments before rescuers arrived.

Although the group claimed that the arm was lost in the original rock fall and that the victim’s claims are the result of delusion, it seems that he’s resurfaced five years later in search of revenge. One by one, the friends are attacked, each in turn having an arm cut of. The pacing is uneven, with some protracted exposition scenes, but Alderman does generate some atmosphere and suspense and the movie heads inexorably to a downbeat conclusion.

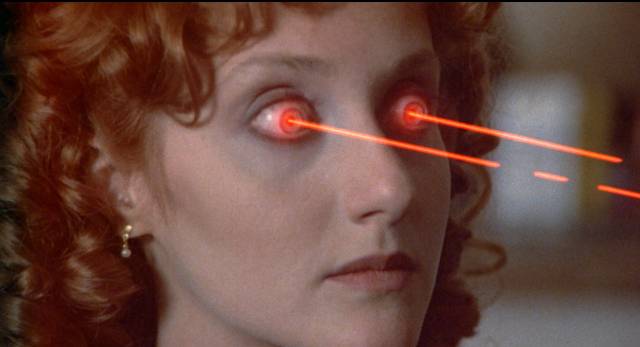

Steel and Lace (Ernest Farino, 1991)

The only feature directed by visual effects technician Ernest Farino, Steel and Lace (1991) is a direct-to-video mix of sci-fi and rape-revenge thriller. When scumbag businessman Daniel Emerson (Michael Cerveris) is acquitted at his rape trial on the perjured evidence of his cronies, his victim Gaily Morton (Clare Wren) commits suicide. Five years later, his associates are being killed in gruesome ways and the apparent perpetrator looks an awful lot like Gaily. It turns out that her grieving brother Albert (Bruce Davison), a brilliant scientist, has created a cyborg in her image and unleashed it on the people who destroyed her.

The artificial Gaily is equipped with multiple weapons to inflict maximum damage on Emerson and his lackeys, but as she tears her way through them, she becomes increasingly aware and develops a conscience. Wren handles her part well, and Davison has his usual jittery intensity. Cerveris is fine as the villain and the script by Joseph Dougherty and Dave Edison adds some nice comic notes to the character – vicious and manipulative, he intimidates old people whose property he wants to buy, although his grand plan is to build … a strip mall.

The running time is padded with an unengaging subplot involving a cop (David Naughton) and his ex-girlfriend (Stacy Haiduk) who team up to solve the case, but the core story is effectively handled and, not surprisingly, the effects are well done.

TC 2000 (T.J. Scott, 1993)

At the start of a career mostly in television, T.J. Scott directed this martial arts/sci-fi action movie in Toronto. In the world of TC 2000 (1993) the wealthy live underground, while the worker underclass struggles to survive among the surface ruins. Our heroes(?) belong to a security team whose job it is to keep the riff-raff out of the privileged underworld, but there’s a surface crime boss who breaks in to steal weapons. One of the team is killed, only to be revived as an enhanced cyborg. Much kicking, punching and shooting ensues.

Producer Jalal Merhi plays the bad guy; the heroes are fitness guru Billy Blanks (whose acting skills are well-suited to late-night promotional videos for his Tae Bo paraphernalia), Chinese martial artist Bolo Yeung and Bobbie Phillips as the cyborg (she’d later turn up in a supporting role in Paul Verhoeven’s Showgirls [1995]). TC 2000 is the kind of thing Albert Pyun has made a career of, though it lacks Pyun’s occasional quirky charm.

Tiger Claws 1-3

(Kelly Makin/J. Stephen Maunder, 1991-2000)

I didn’t realize while I was watching TC 2000 that it had begun as a sequel to Kelly Makin’s Tiger Claws (1991) before morphing into a dystopian sci-fi action movie. Makin’s movie and its two sequels (both directed by J. Stephen Maunder, who also wrote all three) were produced by Jalal Merhi, who stars in all three as cop Tarek Richards, who teams up with other cop Linda Masterson (Cynthia Rothrock, the main reason for watching the movies) to track down a killer using the deadly Tiger Claw technique. This turns out to be Bolo Yeung, who ends up in jail at the end of the first movie, only to be broken out at the start of Tiger Claws II (1996) as part of a plan involving supernatural forces and time travel. Linda heads to San Francisco to re-team with Tarek to investigate more Tiger Claw killings and close the inter-dimensional portal to an ancient Chinese temple.

The third movie in the series (2000) suffers greatly from the almost complete absence of Rothrock, who apparently was only available for a couple of days. The full weight falls on Merhi’s shoulders and he’s just not that interesting an actor. To compensate, the script gets wilder, with villain Stryker (Loren Avedon) summoning three great martial arts masters from the beyond to help him take over the city. To combat the threat Tarek has to be accepted for training by Master Jin (Joseph Kuo favourite Carter Wong) to learn the Black Tiger technique. The mix of Chinese fantasy, martial arts and North American cop movies has interesting possibilities, but diminishing budgets limit what Merhi and his collaborators were able to achieve.

____________

(1.) Being an excessive completist, I picked up a copy of the Australian release of The Punisher from Umbrella after watching Dead Heat. Produced by Cannon at the tail end of the ’80s, it has the grungy, off-hand brutality of that era’s action movies. After his family is killed by the mob, a cop goes underground and sets out to kill every criminal in the city, working his way up to the big boss. Meanwhile, a ruthless Chinese gangster is moving in to take over the drug trade on the coast. The cop gets into the middle of the gang war and facilitates the mutual destruction of everyone involved, while his old partner tries to save him from his vengeful madness. Goldblatt handles the action efficiently and the cast is actually pretty good – Louis Gossett Jr as the partner, Jeroen Krabbe as the mob boss, Kim Miyori as the cool but deadly Chinese interloper … even Dolph Lundgren acquits himself reasonably well, thanks to a script which gives him very little dialogue. The disk itself is impressive, with three different cuts (theatrical, unrated, and Goldblatt’s longer workprint, which despite the rough edges and unfinished quality is a better piece of storytelling than what Cannon ended up releasing) plus a director’s commentary and interviews with Goldblatt and Lundgren. Given the nature of the character, Goldblatt’s B-movie aesthetic works better than the slicker, more expensive approach of Jonathan Hensleigh’s 2004 reboot starring Thomas Jane. (return)

Comments

Ha ha! A terrific set of reviews! I learned about some films I’d never heard of before!