Winter viewing 3: Severin and Fractured Visions

Severin

Naturally I’m behind on my Severin viewing – just can’t stop ordering stuff! I have a couple of outstanding orders still to come, while I haven’t even opened the Nasty Habits nunsploitation box set and still have a long way to go with the folk horror, Andy Milligan and Al Adamson sets, plus a few individual titles (Álex de la Iglesia’s The Day of the Beast [1995] and Perdita Durango [1997], Joko Anwar’s The Forbidden Door [2009]).

Ballad in Blood (Ruggero Deodato, 2016)

Ruggero Deodato, who had gained prominence with a run of provocative, transgressive movies in the 1970s, came out of retirement in his late seventies to make Ballad of Blood (2016), a determinedly sleazy exploitation movie “based on” the Amanda Knox/Meredith Kercher murder case of 2007 – or rather, based on the censorious, morally outraged prosecution’s version of that case. Four friends party all night, blacking out on booze, drugs and sex, and three of them wake next morning to find their friend Elizabeth dead, her throat slashed. The movie follows their struggle to recall what happened as they make fumbled attempts to cover up what they can’t remember, whether it was accident or murder. Steeped in excess – nudity and substance abuse – it paints its unsympathetic characters as a wasted, morally bankrupt generation. Although Deodato retains his skill with creating disturbing imagery, Ballad in Blood lacks the formal rigour of his best work and alienates the viewer rather than implicating him/her in the transgressive behaviour on display. (Several interviews with cast and crew, as well as a couple devoted to the actual real-life case, plus a behind-the-scenes featurette, together totalling more than two hours)

Black Candles (José Ramón Larraz, 1982)

More than a decade after launching his directorial career with the England-set Whirlpool (1970), Spanish filmmaker José Ramón Larraz returned to Britain for the last time to shoot Black Candles (1982). By the early ’80s, the erotic element in his previous work had become tired soft-core exploitation, the sex scenes relegating the horror to the background. A couple travel to England after the death of the wife’s brother and discover the locals in league with her sister-in-law in the practice of black magic. It becomes apparent that the couple are targeted for use in upcoming rituals. This is an upgrade from Code Red’s bare-bones 2016 release, with improved image and new extras. (Commentary and several interview featurettes)

Bloody Pit of Horror (Massimo Pupillo, 1965)

Cheesy doesn’t begin to describe Massimo Pupillo’s Gothic slasher Bloody Pit of Horror (1965), made on the heels of his atmospheric Barbara Steele feature Terror Creatures from the Grave (also 1965). Bloody Pit is a step down in quality, partly perhaps because it replaces elegant black-and-white photography with garish colour. A magazine publisher, a photographer and various models and assistants arrive at a seemingly abandoned castle in search of a suitable background for a photo shoot. They essentially break in only to discover that the owner is a reclusive man who resents their intrusion, but nonetheless permits them to stay overnight. Naturally a mysterious figure begins to kill them off one by one, ostensibly the lingering spirit of a sadistic Medieval executioner. It doesn’t take much effort to figure out the killer’s real identity. The big draw is bodybuilder, and former husband of Jayne Mansfield, Mickey Hargitay giving it his all as the tormented owner of the castle. (Commentary by David DeCoteau and David Del Valle)

Delirium (Peter Maris, 1979)

Peter Maris’s Delirium (1979) began as an (unfinished) riff on familiar ideas from movies like Ted Post’s Magnum Force (1973) and Peter Hyams’s Star Chamber (1983) – a secret group decide that the law is failing society, so they need to kidnap and execute those they consider guilty. In order to flesh out the idea to feature length and make it marketable, a whole new narrative element was concocted. This involved the group’s bad decision to hire a Vietnam vet with severe PTSD to carry out the sentences they hand down … unleashing a psychotic killer on the community. Their attempts to put a stop to his rampage (and protect themselves) result in an escalating body count and their own bloody destruction. It’s an effective example of regional exploitation filmmaking from the period. (Interviews with director Maris and special effects technician Bob Shelley)

Don’t Go in the House (Joseph Ellison, 1979)

From the same year, and far more unsettling, Joseph Ellison’s Don’t Go in the House (1979) is a character study of an unbalanced, socially inept loner (like Willard and May), who gradually accumulates companions in his old decaying house by luring in young women, killing them, and setting them up in a tableau where he can sit and chat. Dan Grimaldi gives a creepy, at times sympathetic performance – kind of a psycho version of Paddy Chayefsky’s Marty (1955) – but what sets the movie’s disturbing tone, and landed it on the British video nasties list, is the horrific, graphic first murder, which co-writer (with Ellen Hammill) and first-time director Ellison depicts with unflinching realism. Although he only implies the subsequent killings, the impact of the first one hangs over everything that follows, filling each new encounter between Donny and a stranger with an overwhelming sense of dread.

Severin’s two-disk set includes three versions – the original theatrical, a toned-down television cut with alternate scenes, and an “integral” cut combining everything from the other two – along with several commentaries and two hours of interviews and featurettes.

The Halfway House (Kenneth J. Hall, 2004)

In The Halfway House (2004), writer-director Kenneth J. Hall attempts to resurrect the ’70s drive-in aesthetic, although he undercuts himself by taking nothing seriously. When the filmmaker treats his own project as nothing more than a joke, it’s hard for the viewer to feel involved in the proceedings. When her sister mysteriously disappears (we already know exactly what happened to her), a young woman goes undercover at a church-run home for wayward girls (though actually the residents are all pretty old for a place like this). The main draw is the presence of Mary Woronov as the head nun, a mean disciplinarian who also happens to be an acolyte of H.P. Lovecraft’s Old Ones, who sacrifices her charges at an interdimensional doorway in the basement. (Several featurettes and a music video)

House on the Edge of the Park (Ruggero Deodato, 1980)

Made immediately after Cannibal Holocaust in 1980, The House on the Edge of the Park is Ruggero Deodato’s next-best-known movie. It hearkens back to Wes Craven’s The Last House on the Left (1972), not just in the similarity of title and the presence of David Hess as a vicious sociopath, but also in its central theme of bourgeois complacency upended by disruptive criminal behaviour. In a prologue, Hess runs a woman off the road and rapes and kills her. Sometime later, a yuppie couple heading to a party stop at the garage where he works and ask for help with some car trouble. As they chat, the couple invite Hess and his dim-witted partner (Giovanni Lombardo Radice) to join them. At the obviously expensive house, it initially seems that the couple and their wealthy friends are trolling the working class pair, but the dynamic quickly shifts and Hess and Radice take charge and begin to torment and abuse what are now their hostages. Violence escalates until towards the end things shift radically when the identity of the tormented yuppies is revealed and the true motive for having brought Hess to the party shows who has actually been in control of events all along.

Severin’s three-disk set includes the feature, a commentary and multiple featurettes on disk one, a feature-length documentary overview of Deodato’s career plus some deleted scenes on disk two, and a six-track CD of Riz Ortolani’s score. This release was initially a bit disappointing because the image was pretty murky, but Severin remastered it and sent out replacement disks with a much-improved image.

Night of the Demon (James C. Wasson, 1980)

For some reason, Bigfoot has long been a presence in popular culture and, despite Harry and the Hendersons (1987), this cryptid has mostly been viewed as a savage threat – from Charles B. Pierce’s The Legend of Boggy Creek (1972) to Ryan Schifrin’s Abominable (2006) and Bobcat Goldthwait’s Willow Creek (2013). James C. Wasson’s clunky Night of the Demon (1980) begins with a traumatized anthropology professor turning up at a hospital. As the cops question him about a missing group of students, we get a series of episodic flashbacks detailing a field trip he led into the woods in search of Bigfoot. The group hear various stories of violent incidents from the people they run into – flashbacks within flashbacks – and the gore is graphic if not particularly convincing. It all leads to a reclusive woman who was raped by the creature and gave birth to a human-Bigfoot hybrid. The acting is incompetent, the structure repetitive, relying on frequent violent encounters (most notoriously one involving a biker who stops to take a leak in the bushes) to stave off audience boredom.

The set’s first disk includes the feature in a 2K scan from an answer print plus multiple interview featurettes. The second disk has a couple of featurettes about cryptids, plus David Gregory’s Ban the Sadist Videos documentary, recently included on Vinegar Syndrome’s Censor Blu-ray (and previously included with Severin’s own House on Straw Hill [1976] release). Speaking of Vinegar Syndrome, they’re planning to release Michael Findlay’s Shriek of the Mutilated (1974) later this year, which on its surface sounds very similar to Night of the Demon … until its notorious twist ending.

Zombie 3 (Lucio Fulci/Bruno Mattei, 1988)

Tacking a previously successful title onto an unrelated movie is one of the oldest tricks in the exploitation handbook, and the Italian film industry applied it perhaps more than anyone else. On the heels of George A. Romero’s Dawn of the Dead (1978), retitled Zombi in Italy, Lucio Fulci struck box office gold with Zombi 2 (1979), aka Zombie Flesh Eaters, which perhaps even more than Romero’s masterpiece launched a worldwide zombie craze. By 1989, that craze was already exhausted, but Fulci took another stab with Zombie 3. Shooting in the Philippines, his health deteriorated and the production was taken over by co-writer Claudio Fragasso and director Bruno Mattei, who was frequently hired to salvage troubled projects.

After a terrorist steals a deadly virus from a military lab, he becomes infected … and when his body is cremated, the pathogen is released into the air and spreads over the island, unleashing yet another plague of the living dead. A couple of soldiers and some tourists team up in the fight for survival while the authorities set out to kill everyone in the infected zone to cover it all up. Zombie 3 is an entertaining grade B riff on very familiar genre tropes (the nonsensical highlight is a severed zombie head which somehow leaps out of a refrigerator and latches onto a victim’s throat with its teeth). (Actor commentary and multiple interview featurettes, plus soundtrack CD)

Zombie 4: After Death (Claudio Fragasso, 1988)

Claudio Fragasso went solo on the quick follow-up Zombie 4: After Death (also 1988) – actually, on the movie itself, the title is just After Death, with Zombie 4 used in promotional materials to make it seem that there was some kind of continuity with the previous movie. This one pretty much ditches the pseudo-science explanation for the living dead and goes back to tradition with a prologue in which a voodoo priest opens a gate to Hell in order to get revenge on a team of doctors he holds responsible for his wife’s death after their experimental cancer cure fails.

Years later, the doctors’ now-adult daughter finds herself on a boat with a team of mercenaries which is mysteriously drawn to that same island. Memories of her childhood trauma from seeing her parents killed by zombies return as she and her companions are attacked by swarms of the living dead, leading to a climax in which that doorway to Hell has to be closed. By now, dumb characters and truckloads of splatter were the essence of this sub-genre and Fragasso delivers exactly that with his usual barely competent finesse. (Several interview featurettes, some behind-the-scenes footage, and a soundtrack CD)

*

Fractured Visions

Fractured Visions is a relatively new British company with only three releases to date. I picked up their two limited edition poliziotteschi, neither of which I’d previously seen.

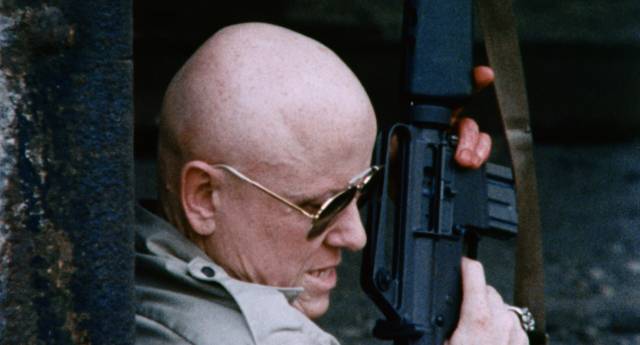

in Umberto Lenzi’s Free Hand for a Tough Cop (1976)

Free Hand for a Tough Cop (Umberto Lenzi, 1976)

Umberto Lenzi made ten poliziotteschi in six years in the ’70s, most of them excellent examples of the genre – in fact, he did some of his best work in this genre. Free Hand for a Tough Cop (1976), the seventh, begins with a neat piece of sleight of hand; the titles play over shots of Monument Valley, with a group of men riding across the desert towards the camera. As the titles end, the camera pulls back to reveal an audience watching a spaghetti western. The screening is in a prison, with guards watching over a rowdy bunch of convicts who yell derisively at the screen, obviously not that thrilled with the evening’s entertainment.

A lone figure makes his way into the prison, pausing to watch the scene from the shadows. When one of the convicts gets up, apparently heading for the can, this man steps out and knocks him unconscious, carrying him out unseen. We eventually learn that the man who entered the prison is Commissioner Antonio Sarti (Claudio Cassinelli) and he’s broken the other man out because he needs his help with a time-sensitive case. The prisoner is “Monnezza”, a small time crook whose connections may help to save the life of a young girl being held for ransom by a gang led by vicious criminal Brescianelli (Henry Silva).

This was the first appearance of Monnezza, who turned up in several films over the next few years, a signature role for the intense and idiosyncratic Tomas Milian. At first reluctant to get involved because Brescianelli is a dangerous man, he reluctantly helps Sarti after being promised a pardon. In fine poliziottescho tradition, Sarti has stepped outside the rules, slipping into violent criminal behaviour himself to defeat the bad guys, who include a couple of psychos who become involved without realizing they’re working for a cop.

There’s some humour in the odd-couple relationship, with Milian verging on the caricatured behaviour which would become his typical style over the next few years, but Lenzi keeps things moving quickly and focuses more on the moral compromises Sarti has to make as he tries to save the girl. It may not be quite up to the standard of Violent Naples, The Tough Ones (both 1976) or Almost Human (1974), partly because it under-uses Silva as the villain, but it’s a solid thriller. (Two commentary tracks and more than an hour-and-a-half of interview featurettes)

Silent Action (Sergio Martino, 1975)

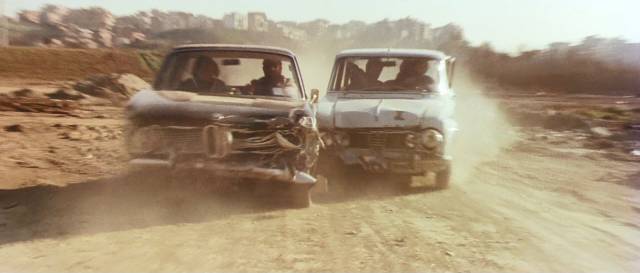

Sergio Martino’s Silent Action (La polizia accusa; il servizio segreto uccide, 1975) is a bit closer to political thrillers like Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion (Elio Petri, 1970) than the more straightforward poliziottescho. The film begins with a series of murders which are staged to look like suicides and the authorities seem to accept them at face value despite the victims being military and government officials. When reporter Maria (Delia Boccardo) approaches Inspector Giorgio Solmi (Luc Merenda) with her suspicions that the deaths are related, he decides to investigate despite his boss’s discouragement.

The more he learns, the more dangerous things get. Bombs are planted, a riot is staged at a prison in order to provide cover for the murder of an inmate who may be a key witness, and smooth intelligence services officer Sperli (Milian again, in a more subdued performance) does his best to divert Solmi’s attention. And naturally, being a Martino movie, there are big action set-pieces – a car chase and a helicopter attack on a mercenary training camp.

It gradually becomes clear to Solmi and Maria that the government, military and police have been infiltrated by a Right-wing organization which is building up to a coup. No one can be trusted, and Martino does a nice job sustaining some ambiguity about who may or may not be involved, including District Attorney Mannino (Mel Ferrer) whose support for Solmi’s investigation never quite seems genuine. This one is Martino at his best, with an excellent cast – poliziotteschi veteran Merenda brings the authority he had honed in numerous movies in which he played cops going against the grain to get to the bottom of things despite a reluctant bureaucracy; Milian avoids his familiar tics as the shifty agent; and Ferrer is comfortable as a man who takes his power and authority for granted.

The one downside to the release is a compromised transfer (in 1080i rather than 1080p for some reason) with a rather dull image. On the other hand, the disk is stacked with a commentary and almost three hours of documentaries and interviews – a one-hour survey of the political and criminal violence which plagued Italy in the ’70s; a 50-minute documentary about Milian; and interviews with Martino, Merenda and score composer Luciano Michelini. And to top it off, there’s a CD with Michelini’s score.

Fractured Visions is obviously a label to watch.

Comments

What is it with Fulci’s characters? They have to be the dumbest characters in filmdom. They don’t even have to run away from whatever is threating them… just walk away for crying out loud. But no, they stand in a corner, they don’t move, they watch, they get eaten.

It took me a long time to get past that, but now I see it as one of his endearing qualities … just put it down to the traumatic effect of staring at walking, rotting corpses – and mechanical spiders!