Winter 2022 Arrow viewing, part one

I’ve watched quite a few titles from Arrow since I last wrote about the company’s releases a couple of months ago. As usual it’s been a mix of movies I haven’t seen before and others revisited after some years. In some cases this has just confirmed old opinions, while for a couple of others I’ve been prompted to re-evaluate at least to a small degree. The upgrades to Blu-ray include half-a-dozen stand-alone titles and a couple of box sets (which I’ll get to after commenting on all the single disk releases).

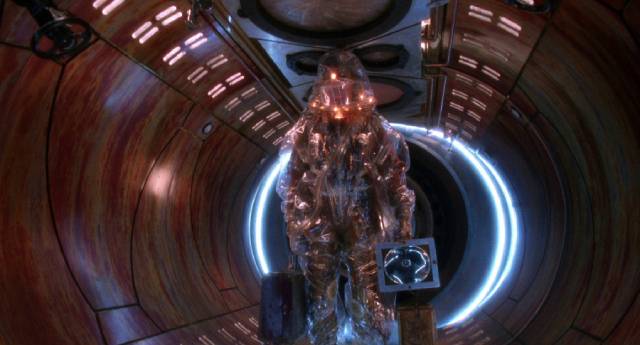

12 Monkeys (Terry Gilliam, 1995)

I’ve always been a bit ambivalent about Terry Gilliam’s 12 Monkeys (1995) because it’s a big, over-elaborate remake of one of the most perfect short science fiction films ever made, Chris Marker’s La jetée (1962). Transforming Marker’s precise, poetic narrative into a two-plus-hour action-comedy starring Bruce Willis and Brad Pitt seems like an absurd act of hubris which obscures the original’s meditation on time, memory and fate. It’s been quite a while since I last watched it (on DVD), but a local store had a copy of the Arrow steelbook on sale, so I picked it up. Maybe all it needed was the passage of time, but I was more engaged on this viewing, managing to suppress my instinct to automatically map Gilliam’s version of the story onto Marker’s – something which inevitably diminishes Gilliam’s movie.

The thread of La jetée does run through 12 Monkeys, though it’s occasionally overwhelmed by Gilliam’s love of excessively detailed design (Marker’s spare, bleak future is here a mad agglomeration of crowded underground prison and vast labs packed with retro-futuristic technology). Gilliam asserts that he had never seen Marker’s film before making his feature, so whatever occurred during the process of adaptation can be attributed to writers David Webb Peoples and Janet Peoples – and since Peoples also wrote (or co-wrote) Blade Runner (1982), Unforgiven (1992) and Soldier (1998), I am inclined to cut him a little slack.

So … divorced from La jetée, 12 Monkeys is a pretty good sci-fi movie suffused with Gilliam’s particular style of dark comedy and nihilism. What is perhaps most interesting about it is the counter-intuitive casting of Bruce Willis as a character with little agency, thrust into a time-spanning plot in which he is assigned the task of saving the world only to find himself inadvertently instrumental in causing the catastrophe he’s been sent back in time to prevent. At times Willis’s confusion and helplessness becomes frustrating – after all, we’re used to seeing him fearlessly taking on vast numbers of criminals and terrorists with little more than his instincts and a string of snappy one-liners. Gilliam’s decision to cast him against type was commercially risky – particularly since 12 Monkeys was one of his attempts to prove to the industry that he could deliver a money-making hit on a relatively small budget (this, like his previous film, The Fisher King [1991], was in effect a job-for-hire taken on to prove that he could be disciplined after the debacle of The Adventures of Baron Munchausen [1988] and his earlier conflicts with Universal Studios during production of Brazil [1985]).

Also cast against type was Brad Pitt, who had established himself as a box office star in a string of big productions after making an indelible impression as an ambiguously charming pretty boy in Thelma & Louise (1991). Here, as the jittery Jeffrey Goines, who rebels against his privileged position as a wealthy kid by playing the revolutionary with a small group of animal rights activists, he serves as the main distraction which leads Willis’s James Cole to make the mistake which guarantees that global disaster won’t be averted. Pitt, with his hyperactive, twitchy performance, has obviously seized on the opportunity to push back against being typecast as someone trapped by his own good looks.

Women have never had a major place in Gilliam’s work, but Madeleine Stowe does what she can to hold her own as the psychologist who comes to realize that Cole’s seeming delusions about being from the future are actually rooted in reality. The rest of the cast is filled out with character actors who add the usual texture to Gilliam’s imaginary world – a world impressively realized on a budget by production designer Jeffrey Beecroft and cinematographer Roger Pratt.

As with previous releases, this one includes Keith Fulton and Louis Pepe’s The Hamster Factor and Other Tales of Twelve Monkeys (1996), the first of the pair’s chronicles of Gilliam’s fraught efforts to make one of his movies against the inertia of studio business interests.

*

An American Werewolf in London (John Landis, 1981)

By one of those odd instances of commercial synchronicity, 1981 brought two separate horror-comedies about werewolves which featured state-of-the-art transformation sequences using new make-up and animatronic effects to make you believe a person really could turn into a beast. Separated by only five months, they changed the way fantasy and horror movies were made, though sadly their physical, on-set achievements have now largely been supplanted by CGI.

I don’t think it’s just because Joe Dante’s The Howling came first that I’ve always preferred it to John Landis’s An American Werewolf in London. It’s more a matter of temperament. I respond more willingly to Dante’s obvious affection for genre and his attempts to recreate the sense of wonder experienced by a child not yet jaded by too many disappointing movies. In contrast, Landis tends to take a sledgehammer to genre, trying to garner laughs by breaking everything in sight. I find most of his movies exhausting and not particularly funny … something which I experienced once again while watching Arrow’s Blu-ray of American Werewolf.

The opening stretch is quite atmospheric, recalling older horror movies as two American tourists get lost hitchhiking in the wilds of England. Naturally they’re warned by unfriendly locals not to stray from the road, and naturally as they bicker they wander onto the moors where they’re attacked by some large animal. One of the friends dies, the other suffers some nasty wounds, but recovers surprisingly quickly. Before you can say “Larry Talbot”, the full moon rises and we get to see in agonizing detail how his body transforms into what looks more like a giant wolverine than an actual wolf.

Rick Baker’s design and the mechanics of the transformation are impressive, but because Landis and Baker were determined to make sure the audience appreciated all the work involved, the sequence is shot brightly lit. The attempt to give a naturalistic, matter-of-fact quality to the effects always has the effect of stopping the movie dead for me – unlike the far creepier, more atmospheric transformation in The Howling, which is part of a dramatically effective scene which advances the narrative.

Landis piles on things like a repetitive waking from a nightmare full of inexplicable Nazi monsters only to find you’re still in the dream gimmick, appearances by the dead, mutilated friend who keeps urging the hero to kill himself, a growing number of other spectral victims with the same suggestion, and then ends everything with a ridiculously overblown action scene when the movie should be reaching its emotional climax. The tormented hero gets lost amidst all the crashing cars and buses in Piccadilly Circus, which all seem to be speeding through London’s narrow crowded streets at about sixty miles an hour. It’s all tonally wrong and by the time Jenny Agutter cries over David Naughton’s dead body, I always feel irritated … just as I did on this occasion.

*

Audition (Takashi Miike, 1999)

I don’t think Audition (1999) was the first Takashi Miike movie I saw – that would have been The Bird People in China (1998), a movie which is still a favourite and which did not in the least prepare me for this director’s more extreme works, like the outrageous Visitor Q and Ichi the Killer (both 2001). Miike has a ridiculously broad range, from flashy violence to slapstick comedy, from thoughtful self-reflexive meditations on cinema to kids’ fantasies with dark undercurrents. Audition, his big International breakthrough, is one of his most mature and carefully considered films, a dark psychological thriller in which the fabric of the characters’ lives unravels in deeply disturbing ways.

Widower Aoyama (Ryo Ishibashi) is persuaded by his young son Shigehiko (Tetsu Sawaki) and his business associate Yoshikawa (Jun Kunimura) that it’s time to look for another partner. A shy man, he goes along with Yoshikawa’s morally dubious plan – use his position as a television producer to “audition” women for a part in a (fictitious) upcoming production. Going through the resumes and head shots of various actresses, he becomes fixated on Asami (Eihi Shiina), a delicately demure young woman. Aoyama goes through the long day of auditions without much enthusiasm, but when Asami comes through the door, he can’t conceal his attraction.

Giving the impression that she’s being considered for the part, he takes her out several times. This is all creepy behaviour, but Miike manages to prevent Aoyama coming across as a sleazy guy taking advantage of the power dynamics inherent in the (fake) situation; he’s quiet, shy and deeply romantic. Although Yoshikawa says he gets an unsettling impression from Asami, Aoyama won’t be swayed; this is the woman whose affections he wants to win.

What he doesn’t know, but Miike doesn’t hide from the audience, is that beneath her doll-like modesty, Asami is seriously damaged – we get glimpses of an abusive childhood during which, while being trained as a dancer, she was molested by her teacher. That abuse has led her to find ways in which to assert control, which she does by imprisoning, torturing and killing men. When she disappears, Aoyama digs into her past, trying to find her again, but he ignores all the warning signs and, remaining infatuated, is defenceless when Asami finally judges him unworthy and punishes him.

While the narrative begins to fragment in the second half, reflecting the tenuous grip both Asami and Aoyama have on reality, Miike manages to maintain sympathy for both characters even as their deep flaws are exposed. Neither is honest with the other, each manipulating the other towards an unspoken end. In this, they are ironically a perfect match – but it’s a match made in Hell, two broken souls locked in a mutually destructive trap created by a combination of lies and desires which are beyond their own control.

*

Come Drink With Me (King Hu, 1966)

There are minimal differences between the image on Arrow’s new edition of King Hu’s genre-transforming Come Drink With Me (1966) and that of 88 Films’ Blu-ray from 2020 – they appear to be from the same master, with just slight differences in framing. The reason for double-dipping so soon is that, while the 88 Films disk has just a Samm Deighan commentary, the Arrow includes a new commentary from Tony Rayns, plus three hours of interviews and documentaries. Like Eureka’s superb King Hu releases, this one situates the film in its historical context and makes clear just why it was so important, both commercially and artistically. As for the film itself, it doesn’t matter how many times I’ve seen it, it remains thrilling entertainment.

*

Gosford Park (Robert Altman, 2001)

Robert Altman’s Gosford Park (2001) also transformed a genre, in this case the Masterpiece Theatre favourite of British class relations centred on the very rich and those who serve them. British television had long delved into the melodramatic possibilities, from the classic BBC adaptation of John Galsworthy’s The Forsyte Saga (1967) and London Weekend’s popular period soap opera Upstairs, Downstairs (1971-75) on. But it was Altman and scriptwriter Julian Fellowes who revitalized the genre with wit and style – and a phenomenal cast – paving the way for Fellowes’ own Downton Abbey (2010-15) and its numerous imitators. To anyone exposed to that flood of class melodramas, the strengths of Gosford Park might no longer be fully apparent, but watching it again I felt the same exhilaration as I did twenty years ago.

Beginning with his third feature, M*A*S*H (1970), one of the defining characteristics of Altman’s work was large casts with overlapping narrative lines (and overlapping dialogue). Many of his films give an impression of loose, improvisatory storytelling, though often on closer inspection they reveal themselves to be complex, intricately constructed narratives carved out of a larger world that we can only catch glimpses of. After the debacle of Popeye (1980), Altman scaled back with a series of smaller movies, many adapted from stage plays, and in the ’90s he alternated obviously commercial properties like The Gingerbread Man (1998) with a return to his ensemble style – The Player (1992), Short Cuts (1993), Pret-a-Porter: Ready to Wear (1994) – with varying degrees of success.

By 2001 it had been some years since he’d had a real hit, but it appeared that something in Fellowes’ work had revitalized him. Managing literally dozens of characters and numerous storylines which give a window (and insight) into the intricacies of the British class system, not to mention the numerous conflicts within a large privileged family and among the many servants who jealously guard their own positions in the moribund social order, Altman makes it all seem utterly effortless – as he did in earlier masterpieces like McCabe & Mrs Miller (1971) and The Long Goodbye (1973) – as if his camera were just fortuitously catching revelatory moments on the fly, simply an observer wandering through this gathering at a country house for a weekend of shooting.

And then, among the petty personal revelations, we gradually discover dark family secrets when the patriarch is found murdered in the library. There are so many layers, so much going on, that the breezy tone, the lightness of touch, seems miraculous. This is a filmmaker at the top of his form, bringing to bear everything he has learned in a career spanning half a century. Other filmmakers attempting this kind of large-canvas storytelling can be seen sweating the effort (think Paul Thomas Anderson in Magnolia [1999]), but Altman makes it look so easy that you become immersed in the narrative without realizing what an incredible amount of work must have gone into creating this impression of effortlessness.

Although Altman made a couple more features and a four-part TV series in the following five years, Gosford Park is the movie which caps his long, uneven career and provides the most pleasure he ever gave an audience – a pleasure untainted by the sourness and cynicism which mars some of his other major films, like M*A*S*H, Nashville (1975) and The Player.

*

Shock (Mario Bava, 1977)

After the problems with Mario Bava’s masterpiece Lisa and the Devil (1974) – unsold, it was cannibalized for the dire House of Exorcism (1975) – and the ignominious abandonment of Rabid Dogs (1974) when funding collapsed, his directing career stalled for several years (throughout the ’60s and into the new decade, he had made two to four movies a year), returning in 1977 for his final feature, which like Lisa and Rabid Dogs signalled his willingness to move in a new direction. Lisa is a Bunuelian fantasy about the disintegration of a bourgeois family; Rabid Dogs is one of the most brutally effective poliziotteschi from a particularly brutal decade in Italian cinema. And Shock (1977), a blend of psychological horror and ghost story, is one of Bava’s bleakest films.

Dora Baldini (Daria Nicolodi), along with new husband Bruno (John Steiner) and young son Marco (David Colin Jr), moves back into the home she once shared with her first husband, who had been a creepy drug addict. Bruno’s job as an airline pilot means he’s frequently away, so Dora has a lot of time to sink into bad memories. It doesn’t help that objects seem to move themselves and Marco begins to say disturbing things which suggest that he may be possessed by the malevolent spirit of his father.

Bava (working with his son Lamberto, who directed some scenes) eschews the baroque style and visual excesses of his earlier work, maintaining a close focus on Dora’s inexorable slide into madness. The atmosphere is dense and claustrophobic, creating a fertile ground for some genuinely startling moments of shock (late in the film there’s a particular moment guaranteed to freak out even jaded viewers, yet it’s so simple in conception and execution that it sums up Bava’s brilliance as a deviser of practical, in-camera effects).

A chamber piece which belongs to the tradition of characters confined to an interior domestic space within which everything familiar becomes strange and menacing (Polanski was a master at this – Repulsion [1965], Rosemary’s Baby [1968], The Tenant [1976]), Shock is a masterful little nightmare which benefits enormously from Daria Nicolodi’s performance, one of her finest and better than anything she did for Dario Argento. This 2K restoration from the original negative is a much overdue upgrade from Anchor Bay’s 2000 DVD; and it comes with substantial supplements, including lengthy interviews with Lamberto Bava and writer Dardano Sacchetti, a lengthy discussion of Bava’s career and the position of Shock by Stephen Thrower, a video essay by Alexandra Heller-Nicholas (it’s her favourite Bava film), a brief interview with critic Alberto Farina, and of course a commentary by Bava expert Tim Lucas.

To be continued…

Comments