Winter 2022 Arrow viewing, part two

This handful of new (to me) Arrow titles are a mixed bag, playing with genre in interesting ways, if not always successfully.

Cemetery Without Crosses (Robert Hossein, 1969)

The Italians weren’t the only ones fascinated by the mythology of the American west. The Germans identified with that mythology, going back to the 19th Century and the novels by Karl May and others; those stories were adapted many times in the ’60s, often starring American expatriate Lex Barker and shot in Yugoslavia. Less common were French westerns, although French companies did pitch in to co-finance a number of spaghetti westerns. Robert Hossein’s Cemetery Without Crosses (1969) is an interesting variation on the genre, totally distinct from the mainstream of Italian westerns even though, like many of them, it was shot in Almeria, Spain.

Hossein, an actor and sometime writer-director, stars as a violent man struggling against his own nature. Naturally, circumstances force him to take up his guns again – this classic set-up aligns the film more with American westerns than their more overtly mythic Italian cousins. Stylistically, the film is quite laconic, with an emphasis on visual storytelling which at least one critic has compared to the work of Jean-Pierre Melville. An air of fatalism hangs over the story of a powerful ranching family crushing anyone who opposes their expansionist ambitions, ultimately bringing about their own destruction.

Having been forced by the powerful Will Rogers (Daniele Vargas) to sell their land, the Caine brothers steal a shipment of gold from him. Ben (Benito Stefanelli) is wounded, but manages to make it back to his homestead – however, Rogers’ men catch up with him and lynch him in front of his wife Maria (Michele Mercier). When the other brothers give her Ben’s share from the robbery, she heads for a ghost town to find gunfighter Manuel (Hossein), who she once loved before marrying Ben. She offers to pay him to get revenge against the Rogers clan.

Manuel ingratiates himself with the ranchers and, having been accepted as a new ally, proceeds to undermine them from within. His plan leads to some very dark places when he takes Rogers’ teenage daughter Diana (Anne-Marie Balin) hostage and she’s raped by Ben’s brothers. Advantage shifts back and forth as the violence escalates, leading to the inevitable climactic showdown in the dusty, wind-blown street of the ghost town. But the final defeat of Rogers and his men doesn’t lead to any sense of triumph, or even satisfaction; tired of it all, Manuel disarms himself and submits to Diana’s revenge.

Cemetery Without Crosses fits into the trend which, by the end of the ’60s, saw a deepening deconstruction of the American mythology of Manifest Destiny and righteous violence. What sets it somewhat apart is a tonal quality, its Frenchness forming a kind of bridge between the traditional Hollywood westerns and the more cynical Italian approach to the genre.

*

Deadly Games (Scott Mansfield, 1982)

The tropes of the post-Halloween ’80s slasher are so firmly embedded in the collective fan’s mind that it can still come as a surprise that filmmakers back in the day were often still feeling their way and using some of those tropes towards different ends. First-time writer-director Scott Mansfield is not a familiar name (he only made one other feature, the even more obscure sketch comedy Imps* [1983]) and he doesn’t seem to have a firm grip on his material in Deadly Games (1982). There’s a series of murders in a small town, the killer wearing black gloves and a ski mask; there’s a heroine back in town after the death of her sister; there’s a psychologically damaged Vietnam vet who runs the local movie theatre (dedicated to classic horror movies), who’s such an obvious red herring that he pretty much points a flashing neon finger at the actual killer.

But mostly there’s a lot of small-town melodrama involving bitchy resentments, infidelity, and a tentative romance between the heroine and the cop investigating the murders. There are long, chatty scenes between old high school friends who’ve gone their separate ways but are now drawn back together by the killing of other members of their social group. Some scenes are effective in an indie-drama way, while the murders sometimes seem to be little more than a necessity imposed by genre expectations.

What keeps it interesting is mostly the cast, led by Jo Ann Harris (formerly the sexually frustrated Carol who’s instrumental in destroying Clint Eastwood’s arrogant soldier in Don Siegel’s The Beguiled [1971]) as heroine Keegan, Sam Groom as deceptively pleasant cop Roger, June Lockhart as Keegan’s Mom, former pro-footballer Dick Butkus as diner owner Joe, and Steve Railsback in full twitchy Railsback mode as Billy, Roger’s old Vietnam buddy. The main thing conveyed by the cast is the boredom of small town life, and it’s out of that boredom that the murders grow. Which means there’s no past trauma behind the slasher plot and, even more of a divergence from the still-emerging formula, everyone involved is an adult – no teens in sight.

*

Doom Asylum (Richard Friedman, 1987)

Richard Friedman’s extremely low-budget, regional cheapie Doom Asylum (1987) is closer to the general run of ’80s slashers. In the obligatory prologue, poor driving ends up resulting in a fatal crash; however, Mitch (Michael Rogen) wakes up on the coroner’s slab and kills the doctors about to perform his autopsy. Driven mad by his injuries and the death of his fiancee, he takes up residence in the hospital basement. Years later a group of young folk (including the dead fiancee’s daughter) decide to stop in the abandoned institution’s grounds for a picnic – the two women relaxing in swimsuits, of course.

Meanwhile, inside the ruins an all-girl punk band are rehearsing. Barbs are fired back and forth between the two groups, but eventually they all find themselves under attack from the disfigured madman in the basement. The cheapness is apparent at every moment, but Friedman manages a few effective kills. Perhaps the most disorienting thing is the presence of Sex and the City’s Kristin Davis making her debut in a slinky blue bathing suit and “smart girl” glasses as one of the potential victims.

*

In the Aftermath

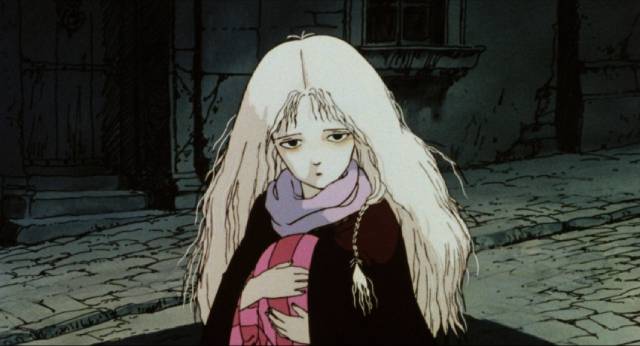

(Carl Colpaert/Mamoru Oshii, 1988)

Although Roger Corman had already left New World by 1988, In the Aftermath continues a tradition dating back to Corman’s days at American International Pictures in the early ’60s: buying a foreign movie and cannibalizing it to provide production value to a new low-budget project. That was how filmmakers like Francis Ford Coppola, Peter Bogdanovich, Curtis Harrington and others got their start, often building movies around the special effects sequences of Soviet sci-fi and fantasy movies.

Carl Colpaert’s In the Aftermath takes the process a step further by building its discount post-apocalypse story around extensive clips from Mamoru Oshii’s early, experimental anime Angel’s Egg (1985). The effect is bizarre, transforming a cheap exploitation movie into a weirdly surreal art film. The live-action sections have a couple of soldiers wandering a devastated world contaminated with radiation and disease in search of food, water and breathable air. They encounter dangerous marauders and a scientist holed up in a ruined hospital/lab – and a young girl dressed in white carrying a large egg.

This girl comes from an alternate (animated) world, itself under attack from space. Her brother tells her to take the egg to Earth and find a worthy human survivor to unlock its power and save the planet from environmental devastation. Colpaert creates some effective transitions between the animated and live-action sections, and also makes the most of a vast, abandoned industrial site in Fontana, California (seen in many other movies, including Terminator 2 and Robocop). Although it seems like it shouldn’t work, In the Aftermath is somehow quite compelling, partly because Colpaert maintains a completely serious tone which short-circuits the absurdity of combining Oshii’s abstract, surreal imagery with the gritty minimalism of the new apocalyptic material. (It’s a pity Arrow didn’t include the complete Angel’s Egg as an extra for comparison.)

*

To Sleep So As to Dream (Kaizo Hayashi, 1986)

Perhaps the oddest discovery of recent months, To Sleep So As to Dream (1986) was the first feature of Kaizo Hayashi, a Japanese director I’d never come across before. It’s an audacious debut, complex and idiosyncratic. I have to admit that I wasn’t entirely on its wavelength and found myself alternately fascinated and irritated as I watched.

Hayashi, who also wrote the script, uses the forms of noir to explore the history of Japanese cinema. Shot in black-and-white, with a slippery sense of period – it seems to exist simultaneously in the early ’30s, perhaps the ’50s, and also the ’80s. It’s a silent film with an elaborate use of sound – the main narrative uses intertitles for dialogue, but also sound effects and music, while at certain times it includes a benshi, the traditional Japanese performer who provides narration and dialogue during silent screenings.

At the start, an elderly woman, famous silent actress Madame Cherryblossom (Fujiko Fukamizu, an actress whose career spanned the ’30s), watches a silent movie in her home (reminiscent of Norma Desmond in Billy Wilder’s Sunset Blvd [1950]). At a critical moment, as the hero confronts a gang of kidnappers who are holding a young woman for ransom, the film abruptly ends without resolution. The old woman sends her servant off to hire private eye Uotsuka (Shiro Sano) to find her missing daughter, Bellflower (Moe Kamura), the hostage in the film-within-the-film.

As the search progresses, becoming more dangerous as Uotsuka closes in on the gang, the two layers become increasingly tangled – Uotsuka’s investigation and the plot of the old movie are one and the same, Bellflower a character played by Cherryblossom fifty years earlier in a film which was never completed, leaving that part of herself trapped in a cinematic limbo. The reason it was left unfinished was that the authorities shut down production because an actress, rather than a man playing a woman, was cast as Bellflower which was a violation at the time of censorship rules. (To complicate things further, at one point there’s a public screening of the film which is interrupted by the authorities for the same reason – so the film is simultaneously finished and unfinished.)

It’s up to Uotsuka to enter the silent film’s narrative and complete it, rescuing Bellflower from the gang and freeing Cherryblossom from the suspended state which torments her.

Hayashi’s style emulates the silent movies it references, shot in 16mm black-and-white with a 1.33:1 ratio. The image is sharp and detailed, with excellent contrast which supports the noirish tone. Extras include an archival commentary from director Hayashi and star Shiro Sano; a new commentary from Jasper Sharp and Tom Mes; plus an hour’s worth of interviews and featurettes, all of which detail the film’s production and the history of Japanese cinema which it references and pays homage to.

*

Box Sets

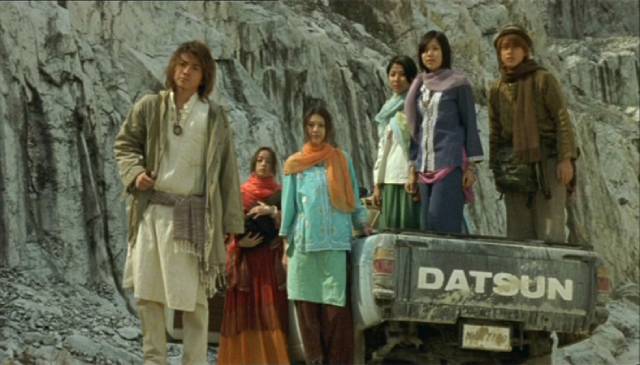

Battle Royale/Battle Royale II

(Kinji Fukasaku/Kenta Fukasaku, 2000/2003)

Kinji Fukasaku was seventy when he made his final masterpiece, Battle Royale (2000), on the heels of another, very different masterpiece, The Geisha House (1998), a remarkable conclusion to a long and varied career. I’ve written before about Battle Royale, so won’t say much here, other than that it holds up really well thanks to Fukasaku’s precise and controlled direction which allows the young cast to give depth to their increasingly traumatized characters while never allowing the visceral action to slacken.

When Fukasaku set out to make a sequel a couple of years later, his health was failing and he eventually had to hand the project over to his son Kenta part-way through the shoot. Battle Royale II (2003) is a disappointment for a number of reasons, but it’s hard to see how it might have been more successful if Fukasaku had been able to complete it himself. The original, in paring down Koushun Takami’s huge novel (adaptation by Kenta Fukasaku), focused on something primal – a society at war with its own children and the trauma of those children facing the horror of being forced to become killers and ultimately the victims of senseless violence.

Leaving the novel behind, the sequel is both larger and yet diminished. It’s a few years after the events of BR and survivor Nanahara (Tatsuya Fujiwara) has become a terrorist fighting against the society which sent him to that island to kill or be killed. And so in the revised Battle Royale program, a high school class is kidnapped, equipped, and shipped off to an island not to kill one another, but to fight and eliminate Nanahara and his ragged group of displaced children and young adults. It’s a war film in which the soldiers are untrained and ill-equipped, those who “recruited” them unconcerned about whether anyone actually survives (the kids on the mission still have to deal with exploding collars and shifting safe zones).

Needless to say, the attacking class and the defenders eventually come to understand their shared interests – it’s not each other but the adults who control society who are the enemy. And so, recognizing what’s occurring on the island, those adults send in the military to wipe out all the kids, who must make a last stand against trained soldiers.

The originality of Battle Royale, and its satirical critique of Japanese society, is lost here in what amounts to a big dystopian B-movie more focused on large-scale action than the psychological impact of the situation on the kids. When I first saw it years ago, it seemed like a sadly unnecessary coda to Fukasaku’s career. I haven’t watched the theatrical version again since that first time, so I can’t really speak to the differences between that and the longer director’s cut included in Arrow’s hefty five-disk set. Twenty-two minutes longer, Battle Royale: Revenge does seem to play better than I remembered, but it still seems less original and more generic than BR. The battle scenes become repetitive and the evolution of the characters remains perfunctory and predictable.

With less to work with, performances are uneven and mostly one-note. Takashi Miike favourite Riki Takeuchi mugs outrageously as the teacher in charge of the operation, completely lacking in Takeshi Kitano’s cynicism and world-weary despair from the original BR, and undercutting the grimness with his cartoonish caricature.

The set includes both theatrical and director’s cuts of both movies, hours of extras both new and archival, a soundtrack CD and a 120-page book about Fukasaku by Tom Mes.

*

Children of the Corn Trilogy

(Fritz Kiersch/David Price/James D.R. Hickox, 1984/1992/1995)

Of the countless Stephen King adaptations made since Brian DePalma’s Carrie (1976) – IMDb lists almost 350 short films, features and television shows – for some reason his 1977 short story “Children of the Corn” has particularly attracted filmmakers. Since the first feature appeared in 1984, there have been almost a dozen sequels and remakes. Murderous kids have long been a genre favourite, as have religious death cults, but Fritz Kiersch’s movie (his first) is really not particularly good, handling the material unimaginatively. Its main point of interest is seeing a young Linda Hamilton just before she hit it big with The Terminator later that year. John Franklin also does well as the creepy kid prophet Isaac who provokes the town’s children to slaughter their parents, but it’s more the idea than the execution which took hold of an audience (on video) and prompted producers to begin making sequels eight years later.

David Price’s Children of the Corn II: The Final Sacrifice (1992) – a title which suggests there were no plans to continue the series – begins right where the first movie ends, with authorities arriving in Gatlin, Iowa, to find all those dead adults and a bunch of traumatized kids who are farmed out to willing foster parents despite dire warnings from an old lady who knows just how evil the kids are.

Journalist John Garrett (Terence Knox) is driving through with his bitter, estranged son Danny (Paul Scherrer) when he gets wind of the events and decides to stop and investigate. Not a smart decision as a new prophet named Micah (Ryan Bollman) continues Isaac’s work proselytizing for He Who Walks Behind the Rows. Leading a group of children who bear some resemblance to the creepy aliens in Village of the Damned (1960), Micah oversees the murder of the old woman who tried to warn people and attempts to recruit Danny to the cause.

It all leads to another ritual sacrifice in the corn field, with Danny’s allegiances ambiguous to the final moments. Price handles the B-movie material more effectively than Kiersch.

For Children of the Corn III: Urban Harvest (1995), writer Dode B. Levenson and director James D.R. Hickox (son of Theatre of Blood’s Douglas Hickox and brother of Hellraiser III’s Anthony Hickox) ship two brothers who survived events in Gatlin to Chicago where they’re adopted by yuppie couple William (Jim Metzler) and Alice (Nancy Lee Grahn), who aren’t aware of the recent horrors out in rural Iowa. The younger brother, Eli (Daniel Cerny), is a creepy little fundamentalist whom we first meet as he kills their father in a cornfield back home, while the older Joshua (Ron Melendez) wants to fit in at school and in the neighbourhood. As Joshua starts a relationship with a girl, Eli begins to assert his power over other kids, drawing them into the cult of He Who Walks Behind the Rows.

There are some surprises as characters you don’t expect to die are killed off, but there are also some major changes to the original concept – in particular, it turns out that Eli, who is not really Joshua’s brother, is actually an ancient demon, while the monster inhabiting the cornfield is not the sinister deity of the previous films but some kind of creature servant summoned by Eli. The movie stretches the limits if its budget for a big, effects-heavy climax, mixing on-set creature effects with some extensive stop-motion, the latter pretty unconvincing but nonetheless fun to see even if the execution falls short of the intention.

I actually enjoyed the two cheaper sequels more than the original movie. All of them look good considering their budgetary limitations. The set (which I picked up in trade at a local used music and movie store) also includes a 4K UHD disk of the original movie, while both sequels are presented in their U.S. domestic versions as well as slightly different international cuts. Each disk is packed with extras – commentaries and featurettes – for those who want to know all there is to know about the trilogy.

Comments