Alien sex and the comedy of self-destruction: two documentaries

Making documentaries about individual people requires an act of creative tightrope-walking. Even the most willing subject may be trying to present a different self-image than the portrait the filmmaker is attempting to create. Because the filmmaker’s interest has been inspired by what makes the subject distinctive and unusual, there are pitfalls – in some cases the filmmaker may trip, in others viewers may perceive the results in unintended ways. One of the most common accusations levelled at documentarians is that they are exploiting their subjects, that they are holding them up for ridicule. This accusation has been made against even such careful and sensitive filmmakers as the Maysles brothers for films as different as Salesman (1969) and Grey Gardens (1975).

Reaction to such films is a complicated three-way collision of attitudes and intentions; the subject’s, the filmmaker’s and the viewer’s. Most such films are the result of a long and intimate relationship between filmmaker and subject, one which no matter how thoughtful may nonetheless have an underlying element of exploitation. But even that may be rooted in the mutual consent of both parties – the filmmaker puts the subject on public display, but the subject is being given an opportunity to present themselves to a larger public than they could ever reach on their own, which has real value if they have something they want to tell the world.

If viewers, who inevitably stand outside the relationship between subject and filmmaker and have no way of knowing what occurred during the process of making the documentary, feel that they are being asked to mock or look down on the subject, then that response grows out of what they themselves feel about what they are seeing; a potential failure of empathy is laid at the feet of the filmmaker rather than acknowledged as the viewer’s own issue. But parsing these feelings is difficult and ultimately irresolvable because we all bring our personal baggage to the party.

Part of what attracts the interest of a documentary filmmaker to a particular subject is idiosyncrasy, something which separates that subject from the norm, and thus the focus is inevitably on difference. The filmmaker – and ultimately the viewer – is searching for some understanding of that difference. We are all seeking what makes these subjects different from ourselves, but beyond that we look for what we may have in common. Therein lies the filmmaker’s balancing act and the value of making such films. They are as much an inquiry into our own nature as they are a display of others’ eccentricities – and so we project something of ourselves into what we are seeing, and in so doing risk passing judgment on these people who have willingly exposed themselves to us.

Two such people are the focus of a couple of documentaries I came across recently (from Vinegar Syndrome partner labels). Although their subjects are very different, they both have a low-key, open-hearted tone (is it just a coincidence that both were made by Canadian filmmakers?), offering no overt judgments from the directors and thus creating room for viewers to bring their own reactions. Perhaps most importantly these two subjects come across with a great deal of charm; they’re both likeable and that carries us a long way as they gradually reveal more about their idiosyncrasies.

Beauty Day (Jay Cheel, 2011)

Years before Jackass, a guy in St. Catherine’s, Ontario, had a local community access show in which he performed do-it-yourself stunts almost guaranteed to cause personal injury (he frequently advised young viewers not to try this at home). During one such stunt, he broke his neck while his camcorder passively recorded the accident, his neighbours’ reaction and the arrival of first responders who didn’t realize at first that they were being taped. Jay Cheel’s Beauty Day (2011) opens with this accident – and returns to it repeatedly to reveal more details; since the stunt involved a swimming pool, the neighbour drags him out of the water, not realizing (as we know) that his neck is broken. Everything about this low-res tape is painful to watch and lays the ground for all that we’ll be shown during the course of the documentary.

Ralph Zavadil seems like a regular guy who created a persona which wouldn’t have been out of place in Bob and Doug McKenzie’s Great White North. Beer-drinking, amused by his own outrageousness, he recreated himself as Cap’n Video in 1990 and performed his do-it-yourself stunts without assistance or rational safety measures until 1995, when the show was cancelled after a couple of ill-advised segments involving animals. His fans complained, but station management decided he’d gone a bit too far – after years of obvious injuries and probable bad influence on young viewers.

After showing us that big accident, the film gives us a compendium of other clips – some painful, others just gross (snorting raw eggs up his nose) – while sketching in Ralph’s background. He went through a painful experience of childhood cancer, which gave him a tolerance for pain and an urge to push the limits of experience. I was reminded at times of Bob Flanagan, subject of Kirby Dick’s documentary Sick: The Life & Death of Bob Flanagan, Supermasochist [1997], another man who turned his childhood – and adult – pain into a form of performance, though Dick’s movie is much more of a downer. Cheel’s account of the saga of Cap’n Video only occupies the first act of the documentary.

The mid-section details Ralph’s relationship with Nancy Dewar, who like Ralph courted danger when she got involved in motorcycle racing. Ralph taped their road trips on the racing circuit, with romantic interludes along the way. This charming love story was derailed when Nancy had a serious accident, for which Ralph felt partly responsible, and spent months recovering from her injuries. Although they parted ways, Nancy is interviewed for the film and obviously retains affection for Ralph.

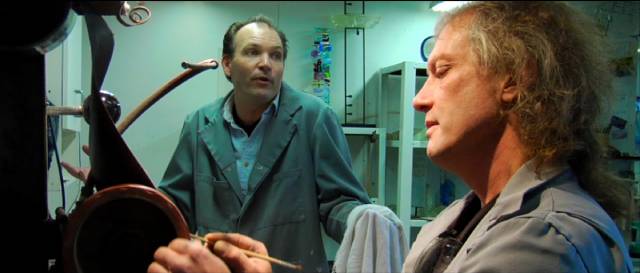

The third act deals with Ralph’s decision to resurrect Cap’n Video for a twentieth anniversary show, which he hopes will serve as a pilot for a revival on cable. He’s older, still fit but not as agile as he used to be – and this time he isn’t working alone, having recruited long-time friend Robert Buick to help. As he develops various stunts and gags, there’s a certain degree of friction with Robert, who exhibits some concern for safety (well-placed as Ralph suffers a number of injuries). In trying to recapture past glory, Ralph approaches the project with the same lo-fi ingenuity, using his old camera as the primary recorder.

Unfortunately, when he submits the edited show to the cable station it’s turned down because of the technical quality (everything today needs to have a hi-def polish, which naturally would work against the whole Cap’n Video ethos). Ralph shrugs off the rejection with an amiable fatalism; the times have moved on and his creation no longer has a place in a media landscape which long ago caught up with and surpassed his form of self-destructive performance. In one of those real-life twists which seem as if they must have been cooked up by a scriptwriter, this disappointment is offset by an unexpected discovery – that Ralph has a teenage daughter he never knew about, with whom he connects and develops a relationship, which may just nudge him out of that lifelong Cap’n Video adolescence.

Everything about Beauty Day is likeable because it rests on the personality of its subject. His enthusiasm and lack of caution as Cap’n Video is infectious, even while his antics might make you cringe or feel queasy – not only is he prone to jump off high roofs and telephone poles, he frequently puts things in his mouth which will make you gag. He is undaunted by injuries both minor and major. Nancy and Robert might express exasperation, but they too are disarmed by his charm. Even his mother Barbara, who doesn’t really understand what he does or why he does it, is more bemused than anything else (she recounts an encounter with kids in the neighbourhood who viewed her with awe as the Mom of Cap’n Video).

If something remains unclear it’s that question of “why?” For all that we learn about Ralph, how he arrived at and expanded on his bizarre alter ego never comes into focus. The risks he takes in becoming this other version of himself are considerable, so the Cap’n is obviously of some psychological importance to him, but director Jay Cheel never quite peels back that layer. Perhaps there’s no great mystery though … why do people skydive and climb mountains and free dive? For some people, it’s vital to themselves to test their own physical and psychological limits; for Ralph, that self-testing takes the form of becoming a ridiculous character for the entertainment of his St. Catherine’s neighbours.

As good as the documentary is, the highlight of the Circle Collective Blu-ray are some substantial extras. I haven’t listened to Cheel’s commentary, but there are some deleted scenes which flesh out the sometimes prickly relationship between Ralph and Robert, and more importantly an hour’s worth of clips from the Cap’n Video show which convey a more direct and concentrated sense of Ralph’s performing persona, and finally the full 21-minute 20th anniversary show which illustrates how he shapes that persona as something more than a mere collection of stunts and tricks. Cap’n Video is a whole other self created to express something we never quite get access to.

*

Love and Saucers (Brad Abrahams, 2017)

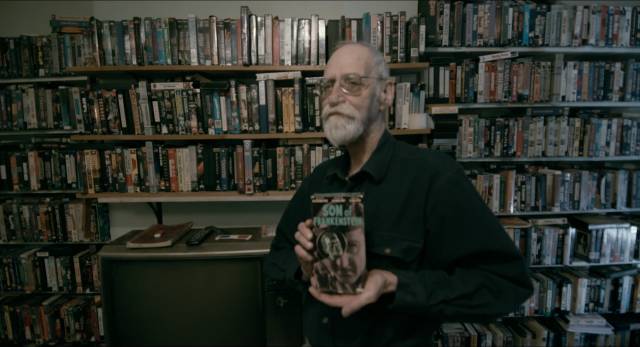

It seems a little easier – though glib – to assume that it’s possible to discern what lies behind the peculiar reality constructed by the subject of Brad Abrahams’ Love and Saucers (2017). David Huggins, a man in his 70s, tells us in the opening clip that he lost his virginity to a female alien in his teens. The rest of this short feature (just sixty-five minutes) elaborates on his lifelong encounters with various aliens and in particular his intense sexual experiences with a particular female. Years into this, he was given permission by these extraterrestrials to document his encounters in paintings and, although he hadn’t painted before, he created dozens of canvasses in which he depicted numerous incidents with different alien species – many displaying his own sexual experiences with them.

This is akin to the common genre of alien encounter literature exemplified by John G. Fuller’s 1966 book Interrupted Journey, which recounts the supposed 1961 abduction of Betty and Barney Hill, and Whitley Strieber’s 1987 Communion, which describes a supposed lifetime of alien encounters, the memory of which Strieber recovered after decades of repression. Since I don’t believe in alien encounters and we now know how notoriously unreliable memory is (and how “recovered memories” are largely post-facto constructions which serve to “explain” experiences more easily explicable in other ways), it’s all too easy to project explanations onto Huggins’ accounts – all the more so after we are given hints of an unhappy, possibly abusive childhood.

As the paintings themselves reminded me a little of Henry Darger’s art, itself a lifelong project to externalize and gain control over childhood abuse, I kept slipping into this easy psychologizing as Huggins spoke … and yet his manner is so easygoing and matter-of-fact that he seems to dispel the very idea of trauma. Apart from the actual concept of sex with aliens, there doesn’t seem to be anything odd about him at all. In fact the people around him – neighbours, his boss at the deli where he works one shift a week, a gallery owner who eventually shows his paintings, and the people who come to the opening who share their own stories of encounters – all take his story at face value. There’s even an academic, Jeffrey Kripal, who accepts the validity of what he has to say, and although Huggins’ ex-wife declined to be interviewed his adult son (now a teacher in Thailand) sees no reason to disbelieve his father.

It’s the matter-of-fact tone, the engaging personality of Huggins himself, who seems unconcerned whether you believe him or not, that makes Love and Saucers so interesting, demanding that viewers examine their own assumptions and beliefs (hence my tendency to search for clues to some underlying psychological explanation for events I can’t take at face value). By maintaining a studied neutrality, Abrahams makes his film a kind of Rorschach test for the audience – you rather wish for David Huggins’ sake that it is all true.

The Terror Vision Video Blu-ray includes a director commentary, a Q&A with Huggins, and multiple additional interviews conducted over Zoom with an odd assortment of people including not only Huggins, Kripal, cinematographer Munn Powell and composer Derk Renemen, but also several writers and artists – including Robert Crumb.

Comments