Miscellaneous May 2022 viewing

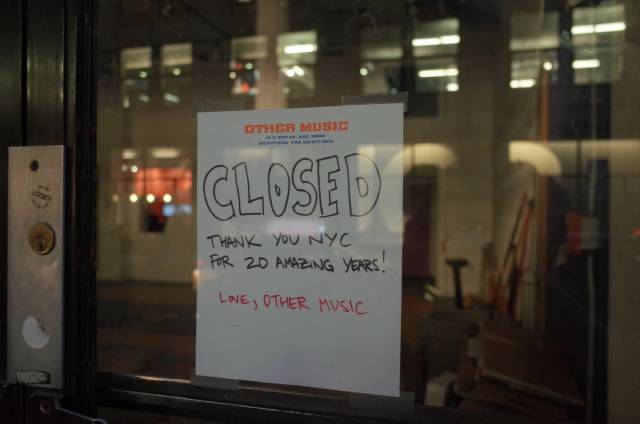

Other Music

(Puloma Basu & Rob Hatch Miller, 2019)

Yet another previously unknown documentary to remind me why good non-fiction filmmaking can be so much more satisfying than fiction. However good a narrative feature is, seldom does one offer some direct connection to our own lives; stories are great, but a dip into reality can connect with parts of our brain only tangentially touched by fiction. On the heels of two recent documentary portraits of eccentric people, Puloma Basu and Rob Hatch Miller’s Other Music (2019) gives a vivid glimpse of an experience all but lost in recent years, an experience I was aware I missed, but wasn’t aware of how intensely I missed it.

Other Music was an independent record store in New York City which became a cultural focal point for two decades until the inexorably changing commercial environment made its owners close shop in 2016. The filmmakers documented the final weeks, interviewing owners Chris Vanderloo and Josh Mandell along with numerous current and former employees and customers. Although my knowledge of music is fairly limited and shapeless – I’d never heard of many of the artists who are touched on in the film – what connected with me was the fascinating dynamics of the store, the complex interactions between knowledgeable staff and customers in search of new experiences.

This brought back memories of my own experience on the staff of a large independent book store and the strange pleasure of psychologically probing customers in order to discern their tastes and interests and lead them to something they probably had no idea would be just what they were looking for. Even more, it brought back memories of endless hours browsing in record and movie stores, the visceral thrill of coming across something I didn’t even know existed until it all but leapt off the rack into my hand.

Being a consumer was different even just a couple of decades ago, a matter of social interactions in three-dimensional space rather than mere clicks on a mouse as you stare at a two-dimensional screen. Watching Other Music, I was continually surprised by a mix of emotions, a warm nostalgia progressively dissolving into a very real sense of loss. By the time closing day arrives and customers share stories of their own experiences in the store, sometimes over many years, I was genuinely moved. This store, located across the street from a huge Tower Records, and standing for an idiosyncratic, anti-corporate idea of consumption, had come to represent an experience which (at least in my neck of the woods) no longer exists. I felt the loss.

The Factory 25 Blu-ray includes a selection of deleted scenes featuring additional interview clips and in-store performances, plus a commentary from the filmmakers and the store owners.

*

Masks (Andreas Marschall, 2011)

I should follow that sweeping generalization about the disappearance of physical stores with an acknowledgement that occasionally there might be a brief echo of that old experience in out of the way corners of the real world. Recently, when I traded in a box full of DVDs and Blu-rays at a nearby used record store, I came across a few oddities and, since a store credit isn’t like real money, I took a chance on some things I knew nothing about, going only on the impression I gleaned from the packaging. It was on that visit that I picked up, among other things, Arrow’s Children of the Corn box set, something I wouldn’t otherwise have bothered to buy; but the real find that day was a German movie I knew nothing about by a filmmaker I’d never heard of, released by a company I’d never come across before.

The company is Reel Gore Releasing and they’ve put together an attractive package in a limited edition slipcase (this one is 2269 of 3000) which includes both Blu-ray and DVD disks, a soundtrack CD and a booklet containing an interview with director Andreas Marschall and a reprint of a review from Kier-la Janisse’s House of Psychotic Women (so, yes, it turns out that I had read about the movie years ago and forgotten it).

Masks (2011) is an obvious homage to the giallo – more specifically to Dario Argento’s Suspiria and Phenomena – but while Marschall fills it with visual and narrative references, he’s a skilled enough filmmaker to avoid mere pastiche and the movie works very well on its own terms. After a failed audition, would-be actress Stella (Susan Ermich) is handed a pamphlet about a small, exclusive acting school. At the school, her audition goes just as poorly, but when she reacts with anger to the mocking response of the teachers and other students, she’s accepted into the program. Her anger reveals some potential.

As she participates in what seem fairly abusive lessons, she gradually learns more about the school, which had been founded by Polish teacher Matteusz Gdula back in the ’70s. The school had been closed down after a series of deaths and Gdula’s own suicide, but his methods are once again being taught – they involve forms of psychological abuse designed to break down all artifice, to provoke direct access to the students’ deepest emotional states. After another student, Cecile (Julita Witt), whom Stella has befriended, disappears, Stella is offered exclusive training in a seemingly abandoned wing of the school.

What she eventually discovers is that the Gdula method doesn’t have much to do with acting, but is instead designed to push students to psychological extremes and eventual madness in order to produce a particular kind of blood chemistry which nourishes the not-so-dead founder of the school. All of this is a far more effective reworking of Suspiria than Luca Guadagnino’s tedious 2018 remake, anchored by a sympathetic performance by Ermich and excellent, stylish digital photography by Sven Jakob-Engelmann, all supported by an effective, eclectically retro score by Sebastien Levermann.

Marschall’s only misstep is a confusing and unnecessary coda which suggests that the whole thing has been a theatrical performance.

The set includes a behind-the-scenes featurette, several deleted scenes, a music video and trailers, and the booklet, plus the soundtrack CD.

*

Rogue Cops & Racketeers

(Enzo G. Castellari, 1976/1977)

For an authentic taste of 1970s Italian genre entertainment, Arrow have bundled a couple of poliziotteschi by Enzo G. Castellari in a set dubbed Rogue Cops & Racketeers. Castellari was a quintessential genre filmmaker, working as effectively in war movies, westerns and post-apocalyptic action as he did in violent crime movies like this pair. The Big Racket (1976) and The Heroin Busters (1977) bracketed his best western, Keoma (1976), and were immediately followed by his World War Two epic The Inglorious Bastards (1978).

Fabio Testi stars in both movies as a typical ’70s cop bucking the system to fight powerful criminal forces on their own terms. While Castellari matches Sergio Martino in the action department, his treatment of a brutal protection racket which holds an entire town in its terrifying grip in The Big Racket is, if anything, more nihilistic than usual. It’s a bleak movie which leaves all its decent characters dead or irredeemably traumatized. Inspector Palmieri (Testi) has to persuade some of the gang’s victims to fight back, eventually building a small commando squad who have nothing to lose because the criminals have taken everything from them (in two cases via vicious rapes). And the finale is an extended, suicidal battle inside an abandoned factory. Along the way, there are car chases (including a spectacular shot of Testi trapped inside a car pushed off a cliff) and a big gun battle at a railway yard.

The Heroin Busters is less intense, focussed less on personal traumas as it deals with an undercover cop (Testi in some eye-searing hippie outfits) working to bring down an international drug ring – the opening section jumps quickly from Hong Kong to the States to South America to Italy, following the drugs’ journey – under the authority of British Interpol agent Mike Hamilton (David Hemmings). Naturally Fabio is repeatedly in danger of discovery by the criminals and under potential threat from the Italian police who don’t know his real identity.

Both movies get excellent new 2K transfers, with each disk packed with extras – interviews with Castellari and Testi and others, including a pair on the films’ respective score composers (Guido and Maurizio De Angelis on The Big Racket and Goblin on The Heroin Busters) by musician Lovely Jon and one with a retired Italian cop who talks about his own undercover experiences and his work as a consultant on a number of movies.

*

Journeys Through French Cinema

(Bertrand Tavernier, 2017)

Although he wasn’t a formal historian of cinema, Bertrand Tavernier’s love of his chosen medium gave him a broad and deep knowledge of film history which informed a number of books and, most significantly, the project with which he concluded his filmmaking career in his mid-70s (he died at 79 in 2021). In 2016, Tavernier made A Journey Through French Cinema, modelled on Martin Scorsese’s A Personal Journey with Martin Scorsese Through American Movies (1995), which itself was part of an international effort to mark cinema’s centenary. Running almost three-and-a-half hours, Tavernier’s documentary was dense and idiosyncratic, squeezing in so much information about so many films and filmmakers that it was both enthralling and exhausting. It also ended with an acknowledgement that It was just scratching the surface.

The following year, Tavernier expanded on the project with a ten-part series for French television – for some reason, released as eight parts on the Cohen Media Group’s two-disk Blu-ray. The more expansive canvas permitted Tavernier to linger on filmmakers and themes which interested him without the necessity of providing some kind of overall historical arc, giving us an even clearer view of his personal opinions and tastes. Perhaps not surprisingly, given the deeply humanist (and left-leaning) nature of his own work, the series aims to be something of a corrective to the lingering influence of the Cahiers du Cinema critics who became the directors of the Nouvelle Vague; their energies were aimed at breaking the established traditions of French cinema, which they viewed as bourgeois and reactionary. Tavernier, on the other hand, saw himself as rooted in that tradition and carried a lifelong affection for many filmmakers whose reputations had been trashed during the New Wave revolution.

In each episode of the series, Tavernier focuses on a few of these directors, or on a particular tendency in French cinema (one episode is devoted to the use of songs in French movies), explaining what it is that appeals to him in their work and why he doesn’t share his contemporaries’ disdain. While some of these favourites are obvious choices – Jean Renoir, Jacques Becker, Marcel Carne, Henri-Georges Clouzot – others are less well-known, or have faded in stature – Jean Gremillon, Julien Duvivier, Henri Decoin. He also champions Max Ophuls, Marcel Pagnol, Jacques Tati, Sacha Guitry, Maurice Tourneur, Anatole Litvak, and Raymond Bernard.

It’s amusing that he skims over the Nouvelle Vague, though he does take the time to place Agnes Varda as a key figure who for a long time was not admitted into the pantheon of rebels (Jean-Luc Godard, Francois Truffaut, Louise Malle, Claude Chabrol). Although there were significant women directors in the silent period, Varda was only the second notable one in the sound era, following Jacqueline Audry who began her career just after the war; Varda’s first feature, La pointe-courte (1955), laid much of the stylistic groundwork on which the Nouvelle Vague would be built a few years later.

Tavernier’s broad knowledge and personal perspective enables him to draw together such disparate figures as Jacques Tati and Robert Bresson and discover common ground (in their case, among other things, the use of sound and an attention to very specific visual details). Although his observations continually illuminate creative choices he made throughout his career, Tavernier only infrequently makes reference to his own work. The main exception is in the episode which deals with the industry during the Occupation, which not surprisingly sees him bringing in his feature about the period, Laissez-passer (2002), which dramatizes the experiences of those who navigated the treacherous terrain between resistance and collaboration.

Perhaps his largest effort at rehabilitation deals with those filmmakers most vigorously dismissed by the Cahiers critics, those who most clearly represented what was contemptuously labelled the “cinema of quality” – Rene Clement, Jean Aurenche (who wrote or co-wrote five of Tavernier’s features), Pierre Bost (who wrote or co-wrote three) and Claude Autant-Lara. Where the Nouvelle Vague directors wanted a radical break with the past, Tavernier saw himself as part of a continuous flow which made its inexorable way from the origins of cinema through the many turbulent upheavals of the 20th Century; he acknowledges his debt to his (often flawed) forebears and sees his own work as a continuation of an on-going communal effort.

Journeys Through French Cinema is rich, informative, sometimes surprising – it occasionally challenges long-held ideas and in episode after episode introduces names and titles not previously encountered, making you want to track down and discover for yourself what had inspired and shaped Tavernier’s own substantial body of work.

Comments