Murder, mayhem, sex and madness from Arrow

in Robert Day’s The Initiation of Sarah (1977)

The Initiation of Sarah (Robert Day, 1977)

Success inevitably breeds imitation. From the 1960s through the ’80s, theatrical success often led quickly to made-for-television copies of recent hits. This was less risky than trying to duplicate that theatrical success. With the networks competing for audiences and changes in production and distribution leading to the decline of theatrical double-features and B-movies, pulp entertainment shifted to television. It was cheaper to produce TV movies than it was to license theatrical features for broadcast and because there were schedules to fill, a remarkable number of these movies were made, often serving as pilots for potential series.

For those of us who were around back then, the late 1960s and ’70s were surprisingly rich in effective low-budget genre movies made for the tube. This was the time of Paul Wendkos’ Fear No Evil (1969), John Newland’s Don’t Be Afraid of the Dark (1973), Steven Spielberg’s Duel (1971), Dan Curtis’ Trilogy of Terror (1975), Frank De Felitta’s Dark Night of the Scarecrow (1981) and dozens of others. While many might have been rather pedestrian because of content restrictions, writers and directors could be surprisingly creative in the ways they conjured up unsettling atmosphere and suggestions of shock and violence without the freedom to be explicit enjoyed by those making theatrical features.

When Brian De Palma struck box office gold with his stylish adaptation of Stephen King’s first novel, Carrie (1976), it didn’t take long for its key elements to be recycled on television. The Initiation of Sarah (1977), the first professional writing credit for Tom Holland (whose treatment was turned into a script by television veterans Don Ingalls, Carol Saraceno and Kenette Gfeller), was directed by Robert Day who had begun his career in England with various comedies, horror movies and TV shows before relocating to the States in the mid-’60s. Its borrowings from Carrie are obvious, but it manages to succeed on its own terms for the most part.

Sarah (Kay Lenz) is a shy, introverted girl who has telekinetic powers over which she has no control; they emerge when she’s angry or particularly upset. In the opening scene, at a beach party on the eve of her departure for college, a jerk begins to maul her sister Patty (Morgan Brittany) in the surf and Sarah gives him a hefty psychic clout. Patty is vaguely aware of the power, but doesn’t acknowledge being rescued, though the two girls are obviously close.

The next day, their mother sees them off, eager for Patty to join her old sorority, while barely registering Sarah. We learn that Sarah was actually adopted, a fact which remains an unresolved plot thread – there are hints later in the story, but we never learn who Sarah’s parents were (possibly she and Patty share the same father, but had different mothers). Arriving at the college, Patty is immediately spotted by the mean girls of her mother’s sorority, Alpha Nu Sigma, led by glamorous bitch Jennifer Lawrence (Morgan Fairchild), who immediately wants to recruit her … while pointedly ignoring Sarah.

When the latest arrivals “audition” for the various sororities, Patty is chosen by ANS, while Sarah’s only offer comes from the underdog Phi Epsilon Delta, or as the mean girls have it “Pigs, Elephants, Dogs”. As viewers, we see the latter as obviously more desirable – the misfits are a much nicer bunch who are immediately accepting of one they recognize as their own. In particular, the nervous introverted “Mouse” (Tisa Farrow, just a year away from Lucio Fulci’s Zombie), is drawn to Sarah in what we can now easily see as a coded lesbian attraction.

As Sarah settles in at PED, Jennifer works hard to drive a wedge between her and Patty – ANS are her family now and she has to disavow her embarrassing adopted sibling. Needless to say, the stress of this new social environment amplifies Sarah’s telekinetic potential – after she comes close to unthinkingly killing Patty, she attracts the attention of graduate student/teaching assistant Paul Yates (Tony Bill) who tries to cure her of her “delusion”. But there’s a counter force in PED’s alcoholic house mother Mrs. Hunter (Shelley Winters), who recognizes Sarah’s power and sets out to use it in her plan to destroy ANS. There’s a decades-long feud between the two houses going back to an incident in which Mrs. Hunter, as a student, was held responsible for the death of a pledge.

The Carrie parallels are many: the shy, introverted teenager; the mean girl who engineers a public humiliation with the help of her compliant boyfriend (here, rather than a bucket of pig’s blood, Sarah’s best dress is covered with mud and rotten produce); the climactic display of psychic power … though the latter is limited to transforming Jennifer into a shrivelled hag and destroying the manipulative substitute mother, with Mrs. Hunter consumed by fire as she prepares to sacrifice Mouse to consolidate PED’s ascendancy over ANS.

Although the narrative is a bit bumpy because of the structure imposed by television (it has to pause repeatedly for ad breaks), performances are generally good. Winters is doing her usual late-career hammy thing, but Lenz is effective as she gradually gains self-confidence and masters her power, and Farrow is touching as a damaged soul who finds her own confidence through her emotional attachment to Sarah. Budget constraints and network rules keep the climax modest and bloodless, which limits the satisfaction of seeing Sarah’s power finally unleashed, but overall The Initiation of Sarah is an enjoyable variation on a familiar theme.

Arrow’s Blu-ray features a 4K scan from the original negative, supplemented with a commentary from TV-movie authority Amanda Reyes, a queer appreciation by critic Stacie Ponder and programmer Anthony Hudson, a visual essay on the movie’s connection to second-wave feminism by Alexandra Heller-Nicholas, an interview with critic Samantha McLaren about witchcraft and psychic powers in post-Carrie TV movies, and an interview with Tom Holland about his professional first writing credit.

*

Edge of Sanity (Gérard Kikoïne, 1989)

Along with Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818) and Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897), Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1886) was one of the key texts of 19th Century horror. A fairly brief novella, reputedly written in three days after Stevenson had a dream which formed the core of the story, like Frankenstein it blends a kind of proto-science fiction with a moral enquiry into human nature. The question which intrigued Stevenson was how an individual could embody both good and evil. In the story, altruistic Dr. Jekyll searches for a formula which might split the individual so that evil would be excised and the person become purely good. The experiment naturally backfires and the freed evil, no longer held in balance, overwhelms the good.

This binary conception of human nature is rooted more in religion than science, but in the 1880s psychology was still crude and exploratory. The appeal to early filmmakers (the first adaptation was made in 1908) was the elegant simplicity of the idea, requiring less elaborate treatment than the more complex Frankenstein or Dracula. Since that first silent short, the novella has been adapted dozens of times – in fact, it was a more popular candidate for adaptation in the silent era than either of its rivals, with three productions in 1920 alone, including John Barrymore’s striking portrayal in John S. Robertson’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, Conrad Veidt in F.W. Murnau’s Der Januskopf and a now largely forgotten short feature by J. Charles Haydon, starring prolific silent actor Sheldon Lewis.

Like both Frankenstein and Dracula, Jekyll and Hyde forcefully entered modern pop culture consciousness in 1931 with Rouben Mamoulian’s pre-Code landmark adaptation starring Frederic March. And like the respective films of James Whale and Tod Browning, Mamoulian’s feature established key narrative elements which became more or less standard in all the versions which followed – these three movies in effect replaced their 19th Century sources in the popular imagination. How many viewers know that Dracula could walk about freely in daylight rather than being disintegrated by the sun’s rays? Or that a young medical student named Frankenstein did his work in an attic without any elaborate laboratory equipment?

What Mamoulian’s version (adapted by Samuel Hoffenstein and Percy Heath) added to Stevenson’s story was the Freudian idea of repression and the sexual underpinnings of human psychology. What is unleashed by Jekyll’s experimental drug is not mankind’s primal animalistic nature but rather the unfettered libido. This change introduced a new element to the story in the form of a showgirl/prostitute who becomes the object of Hyde’s brutal attention, a character which shows up in one form or another in most of the subsequent adaptations, even the over-produced and watered-down 1941 MGM version directed by Victor Fleming with Spencer Tracy inappropriately cast in the dual lead.

With so many adaptations over the years, it became increasingly difficult for filmmakers to come up with anything original to add to the story. Although Jean Renoir made an interesting version for French television in 1959 (with Jean-Louis Barrault giving a genuinely disturbing performance), the ’60s saw several plodding period adaptations which suffered from a dull sense of obligation to a classic (Terence Fisher’s The Two Faces of Dr. Jekyll [1960], Charles Jarrott’s The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde [1968], Stephen Weeks’ I, Monster [1971]). Inevitably, the ’70s saw more overtly exploitative releases like Hammer’s Dr. Jekyll & Sister Hyde (Roy Ward Baker, 1971), with its gender switch; Dr. Black, Mr. Hyde (1976), William Crain’s follow-up to Blacula (1972); and the David F. Friedman-produced roughie The Adult Version of Jekyll & Hyde (also 1972). There were even comedy variations like Jerry Lewis’s The Nutty Professor (1963) and Charles B. Griffith’s Dr. Heckyl and Mr. Hype (1980), and a musical version starring Kirk Douglas made for television in 1973.

Although Mamoulian’s film remains the gold standard of mainstream adaptations, my favourite is probably Walerian Borowczyk’s The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Miss Osbourne (1981), an elegant, erotic assault on bourgeois hypocrisy steeped in Gothic atmosphere. But this is now joined by a previously unknown version by French director Gérard Kikoïne just released on Blu-ray by Arrow. Edge of Sanity (1989) drifts even further from reverence for the source, but is a fascinating, visually impressive variation which benefits from interesting design by Jean Charles Dedieu and striking photography by Tony Spratling.

The big draw, however, is Anthony Perkins in one of his final roles as Dr. Henry Jekyll and Mr. Jack (not Edward, for a soon-to-be-obvious reason) Hyde. Perkins, of course, brought a lot of history to the part; although he had played a variety of roles in film and on television in the ’50s, he had been indelibly fixed in the audience’s mind as the twitchy, unbalanced Norman Bates in Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960). He continued to have a varied career, but repeatedly returned to parts which carried echoes of Norman, such as Noel Black’s Pretty Poison (1968), which used that image to play with audience perception, and Curtis Harrington’s TV movie How Awful About Allan (1970). In the ’80s, Perkins resurrected Norman himself in Richard Franklin’s Psycho II (1983) and the self-directed Psycho III (1986).

But perhaps the most important precursor to his Jekyll and Hyde was Ken Russell’s Crimes of Passion (1984) in which he played a tormented street preacher obsessed with a prostitute. In Edge of Sanity, he pushes that already extreme performance further into excess, but what could easily have plunged into self-parody remains controlled and fully in harmony with Kikoïne’s approach to the material. That approach, whether intentional or not, also echoes Ken Russell’s work, particularly in its use of exaggerated design and anachronism – like Russell’s outrageous Lisztomania (1975), Edge of Sanity conflates a 19th Century narrative and setting with contemporary elements; the various prostitutes are dressed in a mix of punk and Goth fashions which rather than disrupting the narrative free it from period constraints which might safely confine it to a distant past.

There are two notable changes to Stevenson’s story. The character’s duality is not as clear-cut in Kikoïne and writers J.P. Felix and Ron Raley’s adaptation – Jekyll is psychologically unstable from the start, his marriage to Elisabeth (Glynis Barber) under stress partly from his obsession with work, partly because of some issue with physical intimacy. The latter is established in the opening sequence, in which a young Henry experiences a particularly traumatic primal scene. He is caught spying on a woman from the hayloft in a barn; she teases him with suggestive poses before her lover arrives, and when the couple are engaged in sex, Henry slips while trying to get a better look, falling from the loft and hanging upside down with a chain caught around one ankle. The angry lover beats him viciously as the woman laughs derisively.

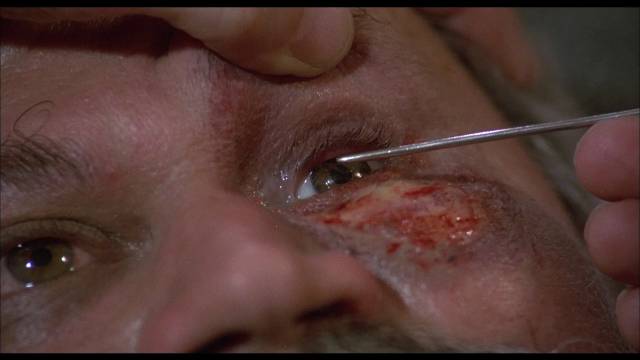

As a physical marker of the trauma, the adult Jekyll walks with a limp and a cane. The inner scars cause him to avoid Elisabeth’s attempts to initiate intimacy and he keeps withdrawing to his lab, insisting that he has to complete his research in time for an upcoming medical conference in Vienna. That work constitutes another departure from the original story. Jekyll is not seeking to discover some secret about human nature; a prominent surgeon (early on we see a disturbing bit of eye surgery), he is working on a new anaesthetic based on cocaine. One evening, an accident in the lab dumps a beaker of liquid onto a heap of cocaine on the workbench, creating a toxic cloud which envelops Jekyll. The drug transforms him into a haggard, red-eyed spectre who finds himself suddenly freed from the tenuous social constraints which have held his warped sense of sexuality in check.

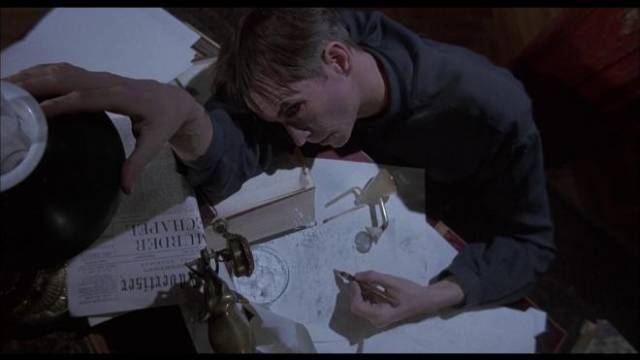

Fleeing the lab, he prowls the streets, accosted by prostitutes and finally led by a persistent tout to an opulent bordello where he meets and becomes obsessed with Susannah (Sarah Maur Thorp). But despite the effects of the drug – which he begins to smoke regularly in a glass pipe, having essentially stumbled on crack cocaine – his deeply-rooted sexual hangups prevent him from indulging freely in debauchery. He manipulates Susannah and the tout to perform for him and, when he accepts the invitations of prostitutes on the street, he indulges in increasingly sadistic behaviour, culminating in a series a brutal murders … which come to be attributed to “the Ripper” who terrorizes London’s East End.

Rather than splitting Jekyll into two separate and opposed personalities, the addiction to crack simply gives license to the Jack Hyde who was lurking inside him, barely contained, since childhood. And in a final departure from traditional treatments of the story, Hyde emerges triumphant rather than being destroyed when Jekyll manages to find the strength to kill himself. Hyde, now in full control, can play the part of Jekyll to maintain cover in a society unwilling to contemplate the possibility that a respected member of the upper class could secretly be a brutal serial killer.

Everything about Edge of Sanity is stylized – while there was some location shooting in London, most of the film was shot in Budapest, giving it a distinctive, unnatural ambience which is heightened by larger-than-life sets (Jekyll’s lab reminded me of Derek Jarman’s designs for Loudun in Ken Russell’s The Devils [1971]). Even though there’s something not quite realistic about these sets, the scenes with Jekyll-as-Jekyll are shot in a fairly naturalistic way, but in the Jekyll-as-Hyde sequences everything is off-kilter with a Bava-like use of unnatural colour and skewed camera angles reflecting Hyde’s unbalanced persona. The apparent restoration of naturalism in the final moments suggest a return to normality, but this is an illusion. If Jekyll and Hyde is the quintessential story of the return of the repressed, this ending doesn’t reestablish repression as classic Hollywood almost always would – what has been released remains free in plain sight, cloaked in social convention.

The final remarkable point about the film is that director Gérard Kikoïne had a career in French porn for fifteen years before making Edge of Sanity, brought onto the project by producer Harry Alan Towers who had begun to work with Kikoïne several years earlier after making a number of films with Jess Franco. Given the director’s background, the elegance and originality of the film seem unexpected. It’s certainly one of the most interesting of Arrow’s recent releases.

The 4K scan from the original negative produces an excellent image which serves the stylized use of colour well. There’s a commentary from David Flint and Sean Hogan; a pair of interviews with Kikoïne (one covering his career, the other focusing on this film); an interview with one of the producers, Edward Simons; an interview with Stephen Thrower; and a talk with academic Clare Smith about Jack the Ripper in popular culture and the inevitable links between the Ripper myth and fictional characters like Jekyll and Hyde and Sherlock Holmes.

*

Crimes of Passion (Ken Russell, 1984)

Speaking of Ken Russell and Crimes of Passion, after watching Edge of Sanity I dug out the Arrow Blu-ray of Russell’s film which I bought six years ago in England and never got around to watching. There was no reason for the delay, other than that I buy far too many movies and just don’t have time to watch them all. Russell has been a favourite since I first saw The Devils in 1971, and while I didn’t always have any particular interest in his subject matter (my knowledge of art and music remains fairly rudimentary), his treatments often piqued my interest.

Roughly speaking his career fell into three periods – the early BBC documentaries about artists and composers which attracted attention for his ability to embody and interpret music in expressionist imagery; the striking features of the late ’60s to early ’80s; and the long years in the wilderness from the mid-’80s to the ’00s, when he struggled to launch his own projects, took jobs for hire and ended up essentially shooting on video in his own back yard just to keep his creative drive alive. In the first two periods, initial critical admiration gradually (or quite suddenly) gave way to a distrust of his “excesses”, which were so un-English, something which Russell shared with another of Britain’s greatest filmmakers, Michael Powell. Both these masters had an ecstatic approach to cinema which was distasteful to tamped-down English sensibilities distrustful of too-open a display of emotion and spirituality.

Following the critical and commercial success of his D.H. Lawrence adaptation, Women in Love (1969), Russell faced a backlash for the excesses of The Music Lovers (1971) and an even more censorious response to his masterpiece, The Devils (also 1971), while his follow-up, The Boy Friend (remarkably also 1971), was largely dismissed by critics. How many filmmakers have had a year like that in their career? Classical music and modern musical theatre, madness and historical horrors, sexual passion and naive romance, all expressed through delirious yet precise image-making in very different genres, all released within a twelve-month period.

For the next six years, Russell concentrated on the genre he had made his own during his tenure at the BBC, the art-bio. Each film received a mixed reception, with the negative usually coming down to the feeling that he was simply unable to control his own creative impulses (John Baxter’s 1973 book on the filmmaker was titled An Appalling Talent). Probably the low point of critical opinion came with the release of Lisztomania (1975), which treated Franz Liszt as the first pop star engaged in a frenzied rivalry with Richard Wagner for the soul of 19th Century music. With Roger Daltry (lead singer of The Who and star of Russell’s adaptation the the group’s rock opera Tommy earlier that same year) as Liszt, Russell pushed the idea of historical verisimilitude out the window in order to make the historical subject relevant to a contemporary audience. It was all too much for critics and baffling to mainstream viewers – what to make of Daltry riding a giant sculpted cock like a rodeo bull?

After the controversial bio-pic Valentino (1977), starring Rudolph Nureyev as the silent movie idol, Russell retreated briefly to television again with a couple of hour-long dramas about 19th Century poets written by Melvyn Bragg, returning to features in 1980 with a work-for-hire. Altered States (1980) had begun production with Arthur Penn directing, but Penn left over creative conflicts with writer-producer Paddy Chayefsky. The production was not a happy experience for Russell; like Penn, he continually butted heads with Chayefsky, who had adapted his own novel and was extremely possessive of every word in the script. Russell, a forceful and stubborn personality himself, refused to treat those words with reverence – whenever protagonist Eddie Jessup (William Hurt) delivered a long philosophical speech about his scientific quest into genetics and psychology, Russell had him rush through the text with breathless enthusiasm – Jessup could well have been the model for Jeff Goldblum’s Seth Brundle in David Cronenberg’s The Fly (1986). Despite the conflicts, Russell managed to impose his own personality on the material, producing a masterpiece of pulp science fiction which manages to conceal the fact that Chayefsky’s story is essentially a pretentious reworking of Jack Arnold’s Monster on the Campus (1958). Dissatisfied, Chayefsky had his name removed from the finished film (the writing credit went to “Sidney Aaron”).

A few more years passed after that experience, with projects falling through, but when Russell headed back to England his agent handed him a stack of scripts and by the time he landed, Russell called and said he wanted to direct one called Crimes of Passion, written by Barry Sandler. There was some trepidation, however, because Sandler’s contract stipulated that he would produce and that no other writers could be brought in to rework the script. This was uncomfortably close to the situation on Altered States, but once Russell and Sandler got together they discovered they were entirely in sync, with any changes to the script being genuinely collaborative.

Crimes of Passion (1984) may be Russell’s last great film, though over the ensuing years he made quite a few which were nonetheless interesting and entertaining, if flawed. Needless to say, it received a mixed reception after being trimmed by censors, though the director’s cut was eventually released on video. Criticized for misogyny, it has a far more nuanced view of sexuality than it was given credit for at the time. Its theme is the ways in which relationships are distorted and corrupted by consumerism, with people slotted into categories defined by the needs of corporate capitalism, subjugated to roles which don’t – and can’t – actually reflect who they really are. Its view of human relationships is pretty bleak, even as the characters struggle to connect with one another with some degree of honesty.

The main character is fashion designer Joanna Crane (Kathleen Turner), who moonlights as high-priced hooker China Blue. In her day life, she’s tamped-down and distant from everyone around her; at night she role plays men’s desires, maintaining control over every encounter, even those is which she is required to be subjugated by the john. Amy Grady (Annie Potts) is her opposite, a woman who has become trapped in the role defined for her by society; she’s a suburban housewife with two kids, a constant desire to acquire more material possessions … and yet remains deeply dissatisfied because she has no idea who she really is or what she really wants, having accepted what she’s been told is the perfect life only to find it empty.

Amy is married to Bobby (John Laughlin), his name signifying emotional immaturity. He’s a man-boy running a small business which is bringing in barely enough to sustain the lifestyle Amy expects. He likes what he does (it’s an electronics store where he sells surveillance equipment) and doesn’t want to change. Out of sync with each other, the couple’s sex life has come to a halt – what they have is the dark side of the ’50s suburban ideal as sold in TV commercials and Hollywood movies.

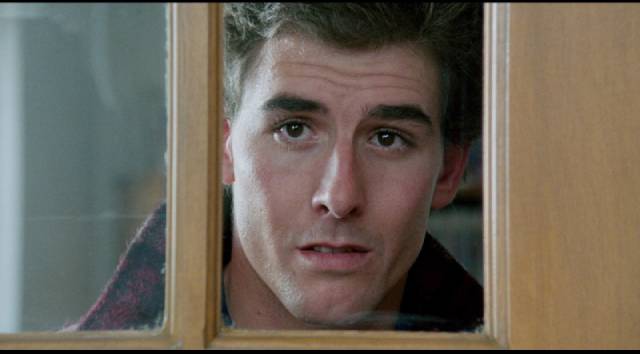

Needing some supplementary cash, Bobby looks for off-hours surveillance work and is hired by Joanna’s boss; someone has been selling his company’s patterns to rivals and he suspects Joanna simply because she keeps so much to herself. Bobby begins to follow her and quickly discovers her secret life. Going beyond the parameters of his assignment, he pays China Blue for a session and discovers the passion he’s been missing at home. Because she’s very good at what she does, Bobby takes her performance as something real … and creepily goes to visit Joanna at her apartment. Naturally, she feels threatened and violated by this forced connection between the two separate parts of her life, but after initially rejecting him, she gradually accepts the possibility of a relationship rooted in an actual emotional connection (we never discover the roots of Joanna’s splitting off of her sexual self from her social self; though she tells a number of stories about her past, they may all be fictions created to satisfy the prior beliefs and expectations of the men she deals with in either persona).

Joanna and Bobby’s attempts to find some kind of authentic emotional (and sexual) connection are complicated by the intrusion into the story of another character, the deranged street preacher Peter Shayne played by Anthony Perkins. Jittery, drug-addled, he haunts the seedier district where China Blue plies her trade, hanging out in peep shows where he gets himself wound up into a frenzy, after which he sets down his little step stool on the sidewalk in front of the entrance, flops open his dog-eared Bible, and rants against sin – his spiel repeatedly slipping into scatological riffs which expose his religiosity as a barely effective form of self-defence against uncontrollable desires of the flesh.

Like Bobby, he becomes obsessed with China Blue, not only visiting her to preach the need for salvation, but taking the room next door to her business apartment and spying on her and her johns through a hole drilled in the wall of what amounts to a shrine to unhealthy desire – pornographic pictures on the wall, an inflatable sex doll which in his delusional state he conflates with an actual woman whom he beats and stabs. In his briefcase, along with the Bible, he carries various sex toys and a sleek metallic dildo with a razor edge.

Also like Bobby, he follows China Blue back to her other life, lurking outside to watch her come and go as he becomes more desperate and feverish. In the final climactic stretch, having invaded Joanna’s space, he expresses two separate but inextricably intertwined desires: he wants her to repent and give up her parallel life of the flesh, but he also wants her to free him of his own enslavement to sexual urges which are driving him mad. By the time Bobby arrives and interrupts the dangerous situation, Joanna and Shayne’s personas have become blurred into a single entity, a figure in which spirit has been made irredeemably mad by flesh and at the crucial moment we, along with Bobby, can’t tell who kills and who dies until the violence is abruptly over.

As in so much of Russell’s work, the performances are uniformly good, though inevitably the more naturalistic Laughlin and Potts are seriously overshadowed by Turner and Perkins, who capture the level of contained excess which characterizes Russell’s best work. Turner, still near the start of her career, is remarkable as a character who shapes her own life and barely holds herself together by playing multiples roles for the many other characters she interacts with; although she had already made a mark with Lawrence Kasdan’s Body Heat (1981) and Robert Zemeckis’ Romancing the Stone (1984), it was her comedic performance in Steve Martin’s The Man With Two Brains (Carl Reiner, 1983) that convinced Russell to cast her. In Crimes of Passion, the fierce defiance of Joanna and China Blue is shot through with humour, giving both sides of the character depth and emotional resonance.

As for Perkins, he obviously relishes the opportunity to immerse himself in Shayne’s feverish derangement, throwing off the repressed veneer of Norman Bates and allowing the festering stew of self-hatred and unwanted desire to flood to the surface. It is this performance rather than the better-known Norman which informs his later appearance as Jekyll and Hyde. Where Joanna has, for a time, been able to keep the two parts of herself in separate compartments, Shayne’s selves are trapped together, constantly at war and driving him into a murderous rage.

Crimes of Passion fares well on Arrow’s Blu-ray, with a 2K restoration from “original film materials”; cinematographer Dick Bush’s stylized use of colour (like Kikoïne’s movie) has a Bava-like quality in the sequences surrounding China Blue, a more naturalistic look for Joanna and Bobby’s daytime lives. The disk includes both the original edited theatrical version and Russell’s director’s cut, the latter containing additional material sourced from an earlier tape transfer, though the dips in quality are barely noticeable. (I watched the director’s cut, of course.)

There’s an archival commentary track by Russell and Sandler, an interview with Sandler and another with score composer Rick Wakeman, both of which provide interesting insights into Russell’s personality and creative process; a selection of deleted scenes, with optional commentary from Sandler; a trailer; and the It’s a Lovely Life music video seen on television in the Grady home, which lays out both visually and lyrically the theme of consumerism and the futile attempt to fill an emotional void with products.

Comments