Zale Dalen’s Skip Tracer (1977)

& the Canadian tax shelter era

The Canadian tax shelter years are legendary, although they lasted less than a decade. From 1975 to 1982, in order to kick start a domestic commercial film industry, the government instituted new rules which allowed investors to write off 100% of the money they put into movie production. Naturally, this didn’t produce an avalanche of cinematic art; for the most part producers taking advantage of the opportunity churned out low-budget genre movies – many of the best-known slasher movies made in the wake of Halloween’s success were made in Canada. Which is not to say that the effort was a waste of time – not only did quite a few of those disreputable movies attain the status of pop classics, still enjoyed by fans today, we might not have seen the long and interesting career of someone like David Cronenberg without the tax incentive. His early films – Shivers, Rabid, Fast Company, The Brood, Scanners – all took advantage of the tax shelter. Actually, it was one of Cronenberg’s movies which triggered the most vitriolic attack on the tax shelter scheme; Robert Fulford’s diatribe against Shivers in the September 1975 issue of Saturday Night magazine actually provoked questions in parliament about the moral and political validity of using tax money to support such offensive trash. Yet the plan stayed in effect for the next seven years. (The text of Fulford’s article is, amusingly, included in the promotional material for Shivers put together by distributor Cinepix.)

Although the genre movies, which frequently attempted to disguise themselves as American, overshadowed everything else, the tax shelter years did actually promote the development of a domestic industry and local talent. While it’s possible to debate the wisdom of pushing film production towards a commercial model – previously, the domestic industry was somewhat overshadowed by the National Film Board, which occasionally went beyond its original social and political documentary mandate to finance progressive features (more often in Quebec, which had its own cinematic identity, than in English Canada) – art wasn’t entirely excluded. Along with your Prom Nights and Terror Trains, there were Richard Brenner’s ground-breaking queer feature Outrageous! (1977), Darryl Duke’s excellent heist movie The Silent Partner (1978), Bob Clark’s fairly elegant Sherlock Holmes/Jack the Ripper mystery Murder By Decree (1979), Louis Malle’s Oscar-nominated Atlantic City and Peter Medak’s The Changeling (both 1980). Jean-Jacques Annaud’s Quest for Fire (1982) also benefited, along with Ivan Reitman’s Meatballs (1979) and Clark’s Porky’s (1981), the latter holding the record as Canada’s biggest box office success for a very long time.

The point is that the period was more varied than is generally perceived. The offence to national identity caused by so many movies disguised as American – most of the horror movies, thrillers like Eddy Matalon’s Blackout (1978) which had Montreal stand in for Manhattan or Alvin Rakoff’s City on Fire (1979), again shot in Montreal – did occasionally produce a positive response to smaller movies which didn’t hide their Canadian-ness. Such was Zale Dalen’s Skip Tracer (1977), shot and set in Vancouver. Well-reviewed, Dalen’s debut feature did well on the festival circuit – but its fate illustrates the main drawback of the whole tax shelter scheme. It might have become relatively easier to produce a small, local film, but there was no firmly established distribution/exhibition structure to guarantee that a movie would be widely seen. In retrospect, I was lucky to get a chance to see the movie in a Winnipeg theatre as it passed briefly through town.

I hadn’t thought about Skip Tracer in a very long time, but was reminded of it when Vinegar Syndrome announced the May release of a movie called Expect No Mercy. This was the latest in their offerings of Canadian martial arts movies produced by and starring Jalal Merhi. I was ready to pass over this as their previous releases of the Tiger Claws trilogy and TC 2000 had exhausted my interest – until I saw that it had been directed by Zale Dalen. I quickly checked IMDb – how many Zale Dalens could there be? – and confirmed that it was indeed the same director … so, despite a low rating and generally risible reviews, I ordered a copy.

But more importantly I was sent on a search for the long-missing Skip Tracer, initially discovering only a bad, lo-res, full-frame copy on YouTube which seemed pretty unwatchable. But then I came across the site of a company I’d never heard of before called Gold Ninja Video. This has the air of a fan site, listing quite a few cheap horror and exploitation movies on disk (at least partially funded by an Indiegogo campaign). Although there’s a real do-it-yourself vibe to the site, there’s also a sense of ambition – releases list commentaries and extensive extras (there’s even a set devoted to Gary Graver, cinematographer, director, pornographer and occasional collaborator with Orson Welles – I’m tempted because of the inclusion of Graver’s unfinished documentary about the making of Welles’ The Trial, although everything on the disk is standard definition and taken from old unrestored masters).

Although it seemed a little risky, I felt compelled to order Skip Tracer from the site – it was a bit expensive with the exchange (although the company is Canadian and ships from inside Canada, it charges in U.S. dollars). The disk arrived quite quickly and I wasn’t surprised to see that it was a BD-R rather than a pressed Blu-ray, but it turned out to play just fine and the important thing was to actually have the movie in a watchable condition, with widescreen framing (1.85:1). Which is not to say that it has a pristine, restored image. Although scanned in 2K, it was taken from a slightly battered print supplied by Library and Archives Canada, which itself was blown up from the original 16mm negative for release in 35mm. Contrast is erratic, with some scenes quite overexposed. But … watchable.

Skip Tracer is a modest movie, conceived to accommodate a limited budget. Dalen shoots in a straightforward style, only occasionally aiming at expressive camerawork. What he focuses on is a well-written script and some decent performances from a cast many of whom, like Dalen himself, went on to mostly television careers. If anything seems to diminish the movie in retrospect it’s the strong memory of Alex Cox’s Repo Man (1984) and James Foley’s Glengarry Glen Ross (1992). Of course, those later works have no direct connection to Skip Tracer, but Dalen was exploring similar thematic territory.

John Collins (David Petersen) works for a Vancouver loan company and for several years has held the record for tracking down delinquent accounts. He’s good at his job and enjoys intimidating people who fall behind on payments. A new, younger employee named Brent (John Lazarus) is not doing well and senses that his job isn’t secure, so he asks Collins if he can tag along to gain some experience. Collins takes some pleasure in putting Brent into risky – and occasionally humiliating – situations. But his own performance is slipping a little – particularly because of his inability to get one customer, George Pettigrew (Alan Rose), to pay up – and his boss begins to put pressure on him; he loses his private office and it looks as if someone else will snag the man-of-the-year title.

With his self-confidence failing, Collins is rocked by the tragic consequences of his persecution of Pettigrew and finally gains a conscience about the unpleasantness of the part he plays in other people’s lives. Unable to continue, he destroys the records of all his clients’ debts and walks away.

For all its modest ambitions, Skip Tracer is nonetheless an effective character study of a man who initially can’t see beyond his own interests and the devastating effect he has on other people’s lives, but watching a younger man desperately trying to emulate him gives him enough perspective to enable him to change. In the strange waters of the tax shelter era, it was a breath of fresh air which suggested that a genuinely Canadian cinema was possible. It’s a tribute to Dalen’s skill that even now, forty-five years later, it seems undated and engaging.

The disk includes a standard definition copy of the full-frame VHS version of the film, a commentary with Dalen and Justin Decloux (the writer, podcaster and filmmaker behind the Gold Ninja Video label), an interview with Dalen covering his career, a featurette in which Decloux attempts to define Canadian Cinema, plus a whole other feature by Dalen, the unreleased Passion (no date, but obviously much more recent). I’m not sure what to make of this movie, which has the feel of a slightly risqué made-for-cable project. It’s about a middle-aged guy who co-owns an antique store with a younger woman with whom he becomes infatuated. This creeps out the woman as well as the guy’s adult daughter who also works in the store. Oh, and his wife is terminally ill – her death is merely a throwaway moment in what is otherwise a troubling “romantic comedy”. When the partner files a harassment suit, the guy hires a lawyer who turns out to be in a lesbian BDSM relationship with her assistant which is carried out openly in the office… The acting is uneven, though some of the performances have charm. But the big obstacle is that the protagonist is kind of a creep – something recognized by the other characters – but we’re expected to be in sympathy with him from start to finish. So – a middle-aged guy’s fantasy about women all finding his creepiness kind of cute and ultimately appealing.

*

Which brings us at last to Expect No Mercy (1995). I read several reviews which warned me that it isn’t very good, so my expectations were low. Perhaps that’s why I was surprised to find myself liking it more than any of the other Jalal Merhi movies I’d watched recently. Like all the others it was written by J. Stephen Maunder and at its core is a poorly conceived gimmick involving virtual reality, which is definitely undermined by extremely rudimentary computer graphics – this was actually made two years after Jurassic Park established an entirely new standard for CGI. Obviously the small budget wasn’t up to the needs of the script.

And yet … Dalen gives the movie pace and a degree of style which overcomes many of the conceptual and material limitations. Billy Blanks (in his third movie for Merhi) is agent Justin Vanier, sent undercover to infiltrate the Virtual Arts Academy, where the evil Warbeck (Wolf Larson) uses advanced technology to speed up the training of elite assassins. Trainees wear VR headsets and face computer generated opponents – which somehow have the ability to inflict actual physical damage (never explained beyond the “this is really advanced technology” trope).

Once inside, Vanier has to contact agent Eric (Merhi), who has been isolated since his contact with the outside was murdered. The pair set out to crack into Warbeck’s computer records to find evidence of the multi-million-dollar contracts he’s been carrying out, in the process drawing in Warbeck’s top technician, Vicki (Laurie Holden), who at first thinks the guys are industrial spies, but eventually joins them when they convince her Warbeck is a killer. It’s a race against time to get the evidence out and to save the life of the next target, a nerdy type named Goldberg (Sam Moses) who is set to testify against shady businessman Bromfield (none other than Brett Halsey aka Montgomery Ford, a perennial presence in B-movies, television and spaghetti westerns over six decades).

Although the fights in the VR realm are a bit underwhelming, those in the real world are well-staged and quite brutal, giving the movie an authentic martial arts feel. This was the fourth and final theatrical feature directed by Dalen – the other two are a well-regarded period hockey bio, The Hounds of Notre Dame (1980), and the punk sci-fi Terminal City Ricochet (1990), which I haven’t seen but will have to look for – made intermittently during a fairly prolific career in episodic television. Despite the low quality computer effects (which have a kind of charm because of their inadequacy), Expect No Mercy is actually an effective exercise in pulp action filmmaking – which bears no resemblance to the unassuming naturalism of Skip Tracer, while illustrating what kind of options the Canadian industry held for directors who didn’t quite have the creative clout of someone like Cronenberg, who was able to break through and establish an international reputation.

*

There’s an in-depth interview with Dalen by Kier-la Janisse on the Montreal-based website Offscreen, about Skip Tracer and the production environment in Canada within which it was made,

Comments

I just got finished watching Skip Tracer on youtube. It’s probably one of the best Canadian dramas that I’ve ever watched. Very entertaining movie and well acted by the principal lead.

I find the reviews you provide to be both informative as well as entertaining. I had never heard of Skip Tracer prior to reading your review!

Glad to hear I led you to this excellent movie!

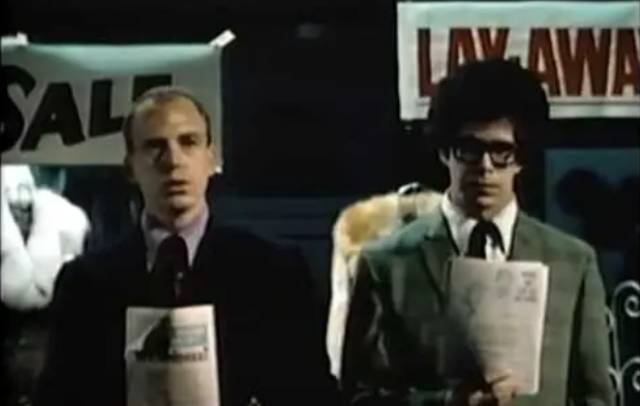

Don’t know who it is at the editing bench, identified as Dale Zalen, but they bear no resemblance to me, Zale Dalen. Not an uncommon mistake.

Aside from that, this was a very fair and generous article. For a time I was the West Coast advisor to the Canadian Film Development Corporation, and spent many meetings pleading with them to expand on the special investment program, under which “Skip Tracer” was made, and fighting off the industry types championing big budget American style production. I was also pleading with them not to go into supporting television production, a move they made because they couldn’t justify the money they were losing supporting feature films. The name change to Telefilm Canada marked the final defeat of that battle.

I wrote a post some time ago on why I believe “Passion” is an underappreciated and historically important film, but that post seems to have disappeared from https://www.artisanmovies.com/ pages. I guess I’ll have to write it again. My main pitch is that it was the first prosumer digital production made completely outside of the movie industry that made no excuses for the technology and actually managed to look like a movie. (the fact that you reviewed it as just a movie kind of makes this point.) Plus I just like its social statements. Check into http://www.zaledalen.com/zaledalen/ in a week or so and I should have it up there.

Thanks for the ink and attention.

My apologies for the error with the photo (and the typo in the caption) – one of the dangers of relying on things other people have posted on the Internet! (I’ve removed the incorrect image and replaced it with the one you sent.)

Thanks for the additional details about the funding situation back in the ’70s. And for the note about the production of Passion; it hadn’t occurred to me while watching it that it was made with non-professional equipment.

I appreciate you taking the time to respond to my post – it was a real pleasure getting to see Skip Tracer again after 45 years!