Digital resurrection

We’ve become so accustomed to digital technology after more than two decades of continuous development and improvement that we tend to take it all for granted. (Who even thinks about how strange it is to record high-definition video with the phone in your pocket?) But occasionally something comes along which suddenly shocks you with its quality. For me this is never the latest big-budget spectacle digitally massaged to the nth degree (I found the widely praised Everything Everywhere All At Once far more irritating than engaging). Rather, in recent experience, it’s actually two very old movies – one ninety years old, the other 103 – which have been meticulously restored with digital tools.

Vampyr (Carl Th. Dreyer, 1932)

Carl Th. Dreyer’s Vampyr (1932) poses particular problems for digital presentation, beyond the well-documented history of the production and the availability (or lack thereof) of film elements. The effort to reconstruct as nearly complete a version as possible back in the ’90s involved multiple archives, each of which possessed battered copies of the various different-language editions – Dreyer had made his first sound film simultaneously in German, French and English – none of which was entirely intact. That reconstruction focused on the German edition (which unfortunately had been slightly cut to satisfy the German censors) and forms the basis of the new digital restoration, just released on Blu-ray by Masters of Cinema. This took a decade of work, with the final task of removing dirt and scratches (more than a quarter-million individual fixes) performed by restorer Claus Greffel at the Danish Film Archive, working alone during the pandemic.

For a digital rendition, an even larger problem lies in the visual style chosen by Dreyer and his cinematographer Rudolph Maté, which uses a lot of diffusion (actually gauze over the lens) to add a soft, luminous fog-like texture to much of the imagery. This deliberate vagueness, combined with the natural film grain, makes it difficult for digital technology to render the original qualities of the photographic image accurately. The softness of the Image Entertainment DVD released in 1998 tended to render many shots as little more than a mush of gray blurs. While this gradually improved with subsequent DVD and then Blu-ray releases, the new disk seems to have captured the imagery much more faithfully, drawing more detail from the source while maintaining what appears to be an accurate rendition of the film texture.

Certainly, watching the film in this form seems more immersive than previous encounters. More than almost any other horror film, Vampyr evokes a pervasive sense of the uncanny. Dreyer achieves this with what, even at the time, were “old-fashioned” techniques going back to the trick photography of Georges Méliès – double exposures, running the film backwards, careful use of light and shadows to suggest immaterial spirits. Beginning with the arrival of Allan Gray (“Julian West”, actually the film’s backer Nicholas de Gunzburg) in a small village, the film seems haunted from the start by an atmosphere of impending doom – the famous image of the man carrying a huge scythe waiting on the dock for the arrival of the ferry reminds us of Death and the River Styx, while the penultimate shot of Allan and Gisele (Rena Mandel) walking out of the woods towards a bright white light suggests figures from ancient mythology emerging from the Underworld. In between, the story exists in a liminal space where the physical and spiritual are inextricably intertwined.

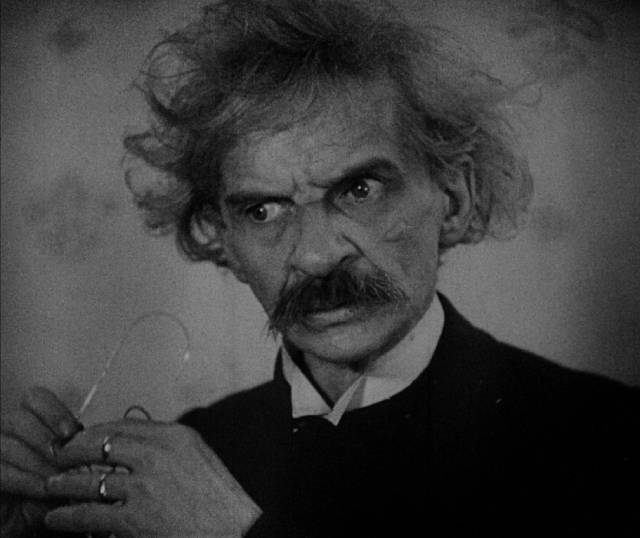

Dreyer and co-writer Christen Jul based their script on In a Glass Darkly, a collection of stories by Joseph Sheridan LeFanu, the 19th Century Irish master of ghost and horror stories. The adaptation is very loose – Vampyr is often considered an adaptation of the book’s most famous story, “Carmilla”, but it actually draws elements from several of the stories in the collection (Allan’s vision of being buried alive comes from the non-supernatural “Room at the Dragon Volant”). The core of the film’s narrative does come from “Carmilla”, but it’s very much changed. The vampire preying on the daughter of a local aristocrat is not a young woman, but rather an old crone (Henriette Gérard), a supposed witch buried in the local churchyard. She holds sway over a population of spirits who inhabit a large building like a derelict factory – their shadows party and dance until she yells at them to be quiet – while the local doctor (Jan Hieronimko) serves as her human helper. (The doctor is the obvious model for Jack McGowran’s Professor Abronsius in Roman Polanski’s The Fearless Vampire Killers [1967], thus providing an oblique link between Dreyer’s film and Hammer’s Gothic horrors.)

One of the strange things about Vampyr, particularly given Dreyer’s other work – The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928), Day of Wrath (1943), Ordet (1955) – is the complete absence of Christian iconography, something deeply embedded in European vampire lore, particularly Dracula-influenced popular culture. No crosses, no holy water, no invocations of God’s power against evil. The film’s world seems deeply pagan, its supernatural atmosphere dominated by the witch and her minions. Those minions meet their own violent ends – after she has been destroyed with an iron rod driven through her heart – when the spirit of the aristocrat they earlier murdered returns and wields some spiritual influence over them; the one-legged guard falls down a flight of stairs and the doctor is trapped in the mill and smothered by a cascade of freshly ground flour.

Vampyr is more mood than narrative, a remarkable use of cinematic technique to evoke the immaterial, the filtered imagery working against photography’s essential quality of capturing the real. The film’s achievement is virtually unique in horror cinema, not simply dream-like but suggesting the fragility of what we perceive as material reality. And yet, though it is now recognized as a classic, it was a commercial failure when it was released in the wake of Tod Browning’s Dracula (Dreyer was frustrated because the distributor held it back until after Dracula’s release even though Vampyr had actually been filmed first). This was a blow, because Dreyer had taken on the production – financed as something like a vanity project by de Gunzburg – after the financial failure of The Passion of Joan of Arc. If he had made the film in an effort to regain commercial viability, he hadn’t succeeded … in fact, it would be another decade before he made his next feature, Day of Wrath (1943), with his final two features coming in 1955 (Ordet) and 1964 (Gertrud).

A painstaking artist, Dreyer himself didn’t seem to take Vampyr as seriously as he did his self-generated projects. And yet to a modern audience, its position as a genre masterpiece makes it perhaps his most accessible film, the idiosyncratic artistry of his approach to the material setting it apart from the more familiar studio horrors of the early sound period. This new digital restoration confirms and consolidates its status as one of the most significant horror films ever made, one which manages to bridge the divide between silent and sound cinema, between 19th Century literary horror and the surreal possibilities of filmmaking which were breaking free of the representational literalism which had seemed inherent in photography. Dreyer’s work contains the roots of a strain of cinema which includes not only the likes of Jean Cocteau, but even someone like David Lynch, artists for whom the apparatus becomes a means of prying beneath the material surface of the world we inhabit.

The Masters of Cinema Blu-ray maintains the label’s high standards, with the restored image supported by a substantial collection of new and archival supplements. In addition to the Tony Rayns commentary from their 2008 DVD, there’s a new track from Guillermo del Toro, who speaks as an enthusiastic fan; a video essay by Casper Tybjerg, and Jorgen Roos’ 1966 half-hour documentary about Dreyer, both also included in that earlier edition; a new interview with Kim Newman about what makes Vampyr unique in vampire cinema; a short documentary about de Gunzburg, who went on to an influential career in fashion in the States; two pieces by music authority and historian David Huckvale, one on the score by Wolfgang Zeller, the other on LeFanu and the adaptation; and finally the two sequences which had been drastically cut by the German censors, taken from a French print.

These couldn’t be reincorporated into the German version because it would be impossible to make the sound match, but it’s interesting to see what was considered unacceptable in Germany at the time: the first sequence shows Allan and the servant opening the witch’s grave and driving the iron stake through her heart – or rather, it implies this with close-ups of the men’s faces and the head of the stake being struck with the hammer, but even in the longer edit we don’t see the stake penetrating the witch’s chest; in the German edit, as the servant plunges the stake into the grave, the picture cuts away immediately and we simply hear a blow of the hammer, but see nothing else until the shot of the witch’s head as it dissolves into a skull. The second, longer sequence shows the death of the doctor in the mill, with the German print reducing the number of shots we see of him struggling as he is gradually buried, gasping for breath.

*

Tih-Minh (Louis Feuillade, 1919)

Once again insecurity rears its head. I’ve loved the films of Louis Feuillade since I first saw his serial Les Vampires (1915) two decades ago. Anticipation had been built up by that time from having read a little about Feuillade (particularly in some essays by Jonathan Rosenbaum) and more particularly from seeing Olivier Assayas’ Irma Vep (1996), which remains my favourite Assayas film. In the following years I got to see Fantomas (1913) and Judex (1917) as they came out on DVD, but I had read (again in Rosenbaum, among other places) that the peak of Feuillade’s accomplishments was Tih-Minh (1919), yet that serial remained inaccessible … until, that is, Gaumont’s release of a restored edition on Blu-ray last year. I finally bought a copy from Amazon France recently and eagerly sat down to watch it over two evenings as soon as it arrived.

First of all, I should mention that there’s some confusion regarding running time. IMDb and Wikipedia list a total for the twelve episodes of 6:58:00, while the Gaumont edition runs only 6:24:50. It’s not unknown that discrepancies between silent film frame-rates and the now-standard 24 frames per second can produce variations, but not on this scale. I haven’t been able to find any information about this, so have to wonder whether IMDb and Wikipedia are simply repeating an error (both sites are well-known for inaccuracies), or whether Gaumont’s disk is missing more than half an hour of the film. Because of the way Feuillade worked, often inventing his stories on the fly as he filmed, it’s hard to say whether anything is missing – the narrative has a contingent quality, with episodes at times echoing one another with similar plot points occurring like variations on a theme, while new revelations change the nature of the story and cause the characters’ identities to shift in new directions as if Feuillade had suddenly come up with fresh ideas which moved the film in previously unanticipated directions. An indication of this can be seen in the first episode’s introduction of all the main characters by presenting portrait shots of the actors as a kind of shorthand to establish roles and relationships – but missing are two key characters who enter the narrative in later episodes when the story veers in a new direction.

But what triggers some slight anxiety, that sense of insecurity, is that I felt I must be missing something crucial because Tih-Minh, Feuillade’s masterpiece, didn’t engage me to the same degree as the earlier serials, particularly Les Vampires and Fantomas. I’m not entirely sure why, though one factor was definitely the performance of Georges Biscot as Placide, the hero’s servant/right-hand man, which unlike the generally naturalistic tone of the other actors (as is common in Feuillade’s work) is a non-stop barrage of silent comedy mugging which I found more irritating than amusing. Perhaps another issue is something which is deeply embedded in the narrative itself.

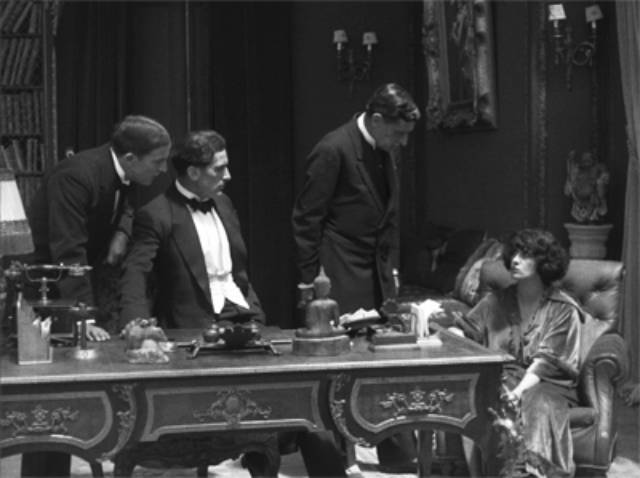

The previous serials deal with conflicts within a national society with strong class divisions, each seeing the bourgeois establishment under siege from a criminal class determined to usurp wealth and power. Tih-Minh, however, is firmly rooted in the structures of 19th Century colonialism, specifically France’s appropriation of Indo-China. The story begins with adventurer Jacques d’Athys (René Cresté) returning home after years away in Vietnam, bringing with him not only cultural artefacts, but also the young woman Tih-Minh (Mary Harald), daughter of a French diplomat and a Vietnamese mother. An orphan, Tih-Minh is to marry Jacques and become a French lady.

Tih-Minh, presented as an almost childlike figure – an unsophisticated representative of exotic orientalism – becomes for the narrative a kind of token representing European domination over the East, a domination which takes two distinct forms, one (the French) benevolent, the other (German) malevolent. Linked to her is a small book which Jacques has also brought back, a Hindu text which (we later learn) was given to Tih-Minh’s father by an exiled Hindu who wanted the Frenchman to guard the secret contained within it. This text becomes the focus of everything which follows because that secret supposedly pertains to a great treasure which is being sought by a trio of criminals who live in a nearby villa.

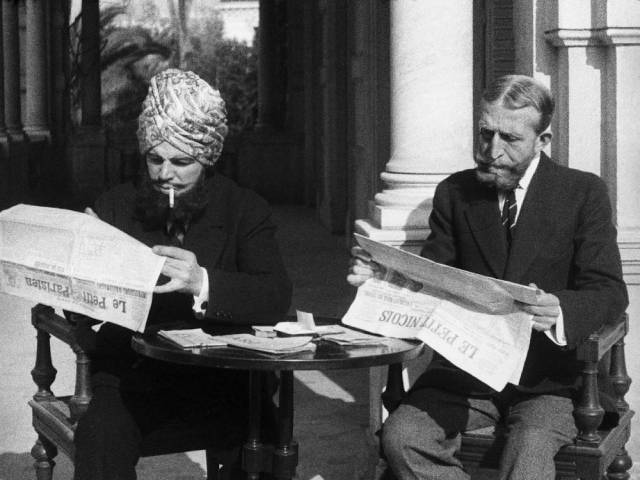

These three – Dr. Gilson (Gaston Michel), La marquise Dolorès (Georgette Faraboni) and the sinister Hindu Kistna (Louis Leubas) – are akin to the villains of the earlier serials, involved in elaborate schemes to defraud and blackmail the wealthy inhabitants of the Cote d’Azur … and apparently conducting a white slavery operation, with a number of bourgeois women drugged and imprisoned in the cellars of their villa. Dr. Gilson has learned that Jacques possesses the book, and that Jacques doesn’t know its true value, so he tries to obtain it by posing as a collector. When Jacques sends Placide to fetch it, the servant notices the cipher written in pencil on the flyleaf and inexplicably pauses to erase it. There’s no logical reason for him to do this, other than that Placide exists to disrupt the schemes of the other characters – in fact, he plays a far more active part in events than the ostensible hero, Jacques, who often seems strangely passive, almost helpless. This sly subversion of class dynamics takes on interesting implications when we realize that the serial was shot quickly in the months following the end of World War One, a conflict which saw the upending of class relations as the “lower classes” were used as sacrificial battlefield fodder by their (often) incompetent “betters”.

Noting the loss of the cipher, Dr. Gilson learns that Jacques has photographed the pages and he embarks on a scheme to get hold of the pictures, a plan which involves kidnapping Tih-Minh and using her as a hostage to force Jacques to hand over what he now knows has great, if still mysterious, value. Tih-Minh is given the drug used on the gang’s other victims, a concoction distilled by Kistna from opium which erases all memory. From here on, the young woman drifts in a mental fog, repeatedly kidnapped and rescued only to be kidnapped again, an exotic possession stripped of her own identity and devoid of agency – like the colonies which European powers seized without regard for their own history and culture.

After much back-and-forth between the heroes and villains, Jacques calls in help from an agent of the British government, Sir Francis Grey (Edouard Mathe), who is able to decipher the code from the book, discovering that its secret not only pertains to great wealth (plundered from the colonies), but also threatens to unleash another great war. Along with this new information, Dr. Clauzel (Marcel Marquet) uses hypnotism to counter the effects of Kistna’s potion of forgetfulness, gradually bringing back Tih-Minh’s memory, and more importantly dredging the young woman’s history from the now amnesiac Dolorès, who provides an extended flashback to Tonkin in which we learn about Tih-Minh’s father, the old Hindu exile, and what happened when Dr. Gilson – who is now identified as a German agent named Marx – got wind of the cipher; he murdered Tih-Minh’s father, but was unable to steal the book, hence his elaborate schemes back in France (though at the serial’s start there’s no indication that the plot has anything to do with global politics as Gilson/Marx and his companions seem only to be using their drug to fleece wealthy people with blackmail and kidnapping).

What irritated me was not the colonial attitudes themselves – these were of their time and a common element in 19th Century adventures – but rather the way Tih-Minh herself was reduced to an object, a mere token in the larger game, which seems odd given that she provides the serial’s title. Her lack of agency in the narrative is frustrating from a modern perspective, particularly given the powerful position afforded other women characters in Feuillade’s work – particularly the dominant Irma Vep in Les Vampires[1]. While World War One isn’t mentioned anywhere, its presence is undeniable, not only in the global military and political implications of the cipher at the heart of the story but also in the upending of class relations previously mentioned, with the largely ineffectual Jacques having far less impact on events than Placide, whose comic persona conveys a kind of contemptuous disdain for a society clinging to its pre-war certainties despite having been exposed by the horrors so recently endured. And yet, despite this implicit critique, the film at no point questions the colonial enterprise; Tih-Minh is an exotic prize which Jacques takes possession of with the full intention of replacing her identity with that of a French bourgeoise. Embedded in the narrative is the implicit acceptance of Europe’s right to dominate and own the rest of the world, with the inferiority of other cultures taken for granted.

All of which is a very long diversion from the point I was trying to make at the beginning of this post: despite my misgivings about the serial, the digital restoration of Tih-Minh is breathtaking. The image looks pristine, as if it had only just been shot, making Gaumont’s Blu-ray possibly the finest representation I’ve seen of what the experience of a silent film would have been like for its original audience (watching this prompted me immediately to order Gaumont’s Blu-ray editions of Les Vampires, Fantomas and Judex). It seems fitting that this quality is applied to a Feuillade serial because one of the most engaging characteristics of his work is the often spectacular location shooting. He thrusts his actors into what often appear to be genuinely dangerous situations – they frequently scale high walls and sheer cliffs, hanging precariously from vines or tree roots. For all the fanciful elements of their narratives, this staging in the real world (as opposed to studio sets) gives Feuillade’s films a documentary aspect as a record of places and styles as they existed a century ago. The clarity and detail of the restoration adds enormously to this valuable quality.

All of which is a very long diversion from the point I was trying to make at the beginning of this post: despite my misgivings about the serial, the digital restoration of Tih-Minh is breathtaking. The image looks pristine, as if it had only just been shot, making Gaumont’s Blu-ray possibly the finest representation I’ve seen of what the experience of a silent film would have been like for its original audience (watching this prompted me immediately to order Gaumont’s Blu-ray editions of Les Vampires, Fantomas and Judex). It seems fitting that this quality is applied to a Feuillade serial because one of the most engaging characteristics of his work is the often spectacular location shooting. He thrusts his actors into what often appear to be genuinely dangerous situations – they frequently scale high walls and sheer cliffs, hanging precariously from vines or tree roots. For all the fanciful elements of their narratives, this staging in the real world (as opposed to studio sets) gives Feuillade’s films a documentary aspect as a record of places and styles as they existed a century ago. The clarity and detail of the restoration adds enormously to this valuable quality.

While the story itself, with its passive heroes and rather incompetent villains, all overshadowed by Placide’s comic antics, frustrated me at times, I was continuously entranced by this record of a world long past. On both an aesthetic and emotional level, the Tih-Minh Blu-ray transported me in a way no big-budget CGI spectacle ever has or can. The past is another world and Feuillade’s art opens a brief window onto this alternate material reality, regardless of the troubling social and historical issues embedded in the narrative.

___________________________________________________

(1.) Seeing Tih-Minh at last to some degree clarifies Assayas’ choice in the casting of Maggie Cheung in Irma Vep. In that film, there is resentment about giving the role of an iconic French character to a Chinese actor, a reversal of the erasure of Asian identity by French colonialism in Tih-Minh, and an attempt to restore some kind of balance which eventually proves impossible as Asssayas’ film collapses in on itself under the weight of cultural and cinematic contradictions. (return)

Comments

This is perhaps my favourite of the many reviews of Vampyr that I’ve read.

“a remarkable use of cinematic technique to evoke the immaterial”

So beautifully said! This captures quite well a certain creative approach that I find so appealing in certain movies, Vampyr included.

Is cinema itself, indeed, uniquely good artistically at potentially “evoking the immaterial”?

But, concerning the absence of Christian iconography in the movie — is there a weird pieta composition perhaps in the very image from Vampyr featured above the text about this topic?

But, anyway, I adore Vampyr! A really cool film. It was a big inspiration, in terms of visual style and mood, for a short movie I directed about people who’ve lost their eyesight but can momentarily regain it during their dream experiences.

True, the image above does evoke familiar representations of the Pieta -although how that applies to this particular dramatic moment is unclear: with the witch filling in for Mary and her victim Christ. My main point was that, while the European vampire is coded in overt Christian terms, more specifically Catholic terms, the vampire like the Devil serving as a validation for the authority of the Church, in Vampyr the obvious symbols – crucifix, holy water, prayer – are absent. The film exists within an older, Pagan context … which is all the more interesting given the Christian underpinnings of Dreyer’s major films, particularly The Passion of Jeanne d’Arc, Day of Wrath and Ordet. But even there, Dreyer displays a more austere type of religion in which Northern European Protestantism is in stark contrast with the flamboyance of southern Catholicism. That starkness reaches its peak in Vampyr where Christian codes are all but entirely absent.