Summer grab-bag, part three: Vinegar Syndrome partners

With an ever-expanding roster of disk producers, my monthly quota of new releases from Vinegar Syndrome’s partner labels has been getting out of hand. I have to become more judicious about what I order, but the sheer range of what’s on offer keeps sucking me in, particularly with odd and obscure titles which play to my taste for fringe filmmaking.

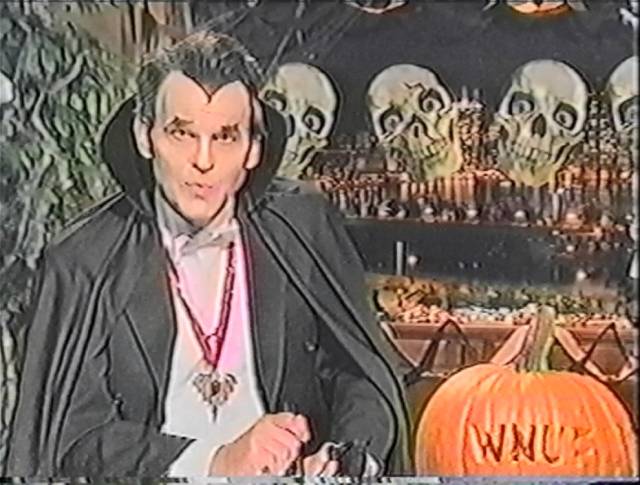

WNUF Halloween Special (Chris LaMartina, 2013)

As found-footage horror goes, Chris LaMartina’s WNUF Halloween Special (2013) is perhaps one of the most “authentic” examples of the genre. Purporting to be a battered old VHS copy of a local television broadcast from October 31, 1987, it provides a convincing simulacrum of what TV-watching was like before everything shifted to cable (and eventually on-line streaming). Production values are rudimentary, everything is frequently interrupted by cheesy commercials (many of which are fast-forwarded on the tape), and the local news anchors give equal weight to a range of stories, from a dentist doing his best to get kids to give up all that Halloween candy to a group of local religious zealots who are stirring up Satanic panic fears about the dangerous pagan holiday.

In the midst of this, reporter Frank Stewart (Paul Fahrenkopf) is doing a remote location report with his producer Veronica Stanze (Nicolette le Faye) from the infamous Webber House, site of a brutal murder two decades earlier and now reputed to be haunted. (It seems likely that LaMartina and his collaborators at least knew of the BBC’s Ghostwatch [Lesley Manning, 1992].) Stewart tries to drum up some anticipation with the small crowd gathered outside the house, many wearing Halloween costumes, some aware of the house’s history, most just trying to get their brief moment on camera.

With Stewart are a couple of paranormal investigators, Dr. Louis Berger (Brian St. August) and his wife Claire (Helenmary Bell), a deglamorized version of the Warrens in The Conjuring (2013) and its sequels, who have brought along their psychically sensitive cat Shadow. The final member of the team is a very nervous priest, Father Joseph Matheson (Robert Long II), who may be needed for an exorcism. The investigation inside the house is as unconvincing as any number of ghost-hunting cable shows, with Stewart trying to conjure some suspense to carry the viewers through the ad breaks … but then, of course, things start to happen. The Bergers’ equipment gets smashed, poor Shadow is killed and mutilated … can the ghost of the original murderer be coming after the team? Stewart has to throw back to the anchors in the studio while he tries to get things back on track.

While the final revelation isn’t too surprising, it’s the incidental details which make the show so entertaining. Particularly, the convincing anchors back at the station, Gavin Gordon (Richard Cutting) and Deborah Merritt (Leanna Chamish), working as hard as they can to fill air time and make whatever they have to present seem significant enough to matter to the audience. The icing on the cake is the commercials; to anyone who experienced pre-cable broadcast television, the commercials were a tedious, unavoidable price which had to be paid in order to see your favourite shows, but now there’s an unexpected nostalgia value in seeing the local carpet warehouse owner touting his deals juxtaposed with a PSA about the risks of drugs and STDs. Although the distressed VHS quality is very convincing (the movie was run through multiple tape generations to produce dropouts and tracking errors, plus the distortions of fast-forwarding through some of the ads), it’s actually the ads which give the show a persuasive verisimilitude.

Not that it provides any real scares; the tone is more of affectionate comedy than genuine horror. The TerrorVision Blu-ray includes two commentaries from LaMartina and the cast and crew, outtakes and bloopers, additional commercials and a demonstration of how the original material was processed to produce the authentic look of an old recorded-off-air VHS tape.

*

Collecting has a number of dimensions, some of which may seem incompatible with others. I have a fair share of acknowledged cinematic masterpieces on my shelves, but also quite a few obscure oddities, movies which few would venture to call “good”, but which nonetheless illuminate cinema from the fringes. Such are three very different recent releases from American Genre Film Archive (AGFA).

Final Flesh (Vernon Chatman, 2009)

Final Flesh (2009) is a conceptual experiment, conceived and written by Vernon Chatman, a prolific writer-producer of absurdist cable content. Chatman wrote four short scripts, variations on the same basic situation – a family (father, mother and daughter) work through obscure, occasionally perverse, issues as they wait for the end of the world – and sent them to four companies which create fetish porn on demand. The four resulting films were then edited together into a short feature.

The film which emerged from this process is strange, funny, unsettling, its impact arising from the discordance between Chatman’s dialogue (the characters talk about the meaning of life in the face of its imminent destruction, and their own personal conflicts and emotions) and the limitations of the actors and technicians struggling to make sense out of scripts which they don’t really understand. They fall back on well-established habits, though the nudity and sexual situations with which they’re obviously comfortable are at odds with the philosophical pretensions of the material. The acting is stilted and amateurish (the porn performers are not used to the dramatic demands) and the technical execution is crude and perfunctory. And yet there’s something oddly engaging about the clash between concept and execution.

Extras on the AGFA Blu-ray are sparse – it would have been nice to hear Chatman discuss the project in a commentary, but all we get are some brief pieces of ephemera, including a music video and some outtakes from one of the four shoots.

Satan’s Children (Joe Wiezycki, 1975)

Another independent oddity from Florida rescued from obscurity by AGFA and Something Weird, Joe Wiezycki’s Satan’s Children (1975), like Thomas Casey’s Sometimes Aunt Martha Does Dreadful Things (1971), confronts the viewer with confusing and problematic gender attitudes. Sulky teenager Bobby (Stephen White) is endlessly nagged by his father and tormented by his stepsister Janis (Joyce Molloy), who takes a great deal of pleasure in provoking sexual embarrassment. After Janis outs him over dinner for his stash of weed, Bobby runs out of the house and heads down the road. In a diner, a predatory older man hits on him, but Bobby is “rescued” by a younger man who offers him a place to stay. To no viewer’s surprise, this guy Jake (Bob Barbour) rapes him at knife point, then calls his friends to come over and party. Out for a joyride, these friends take it in turns raping Bobby in the backseat before dumping him outside town.

In the morning, he’s found unconscious and naked by a group of young people playing in a nearby field. They take him back to what seems to be their commune, where Sherry (Kathleen Marie Archer) is smitten, though Joshua (John Edwards) warns that the Master won’t like having Bobby around because, obviously having been raped, he must be “queer”. Joshua heads down to the chapel, where he prays to a plush goat head above the altar, calling the Master to come and take care of Sherry’s transgression. Sherry, ticked off, lynches several members of the family who we now know are a Satanic cult.

Cult leader Simon (Robert C. Ray Jr) returns and is not happy. He’s also very dismissive of Bobby, who’s obviously a weakling and unworthy of Satan’s attention. Sherry is punished by being buried up to her neck and covered with honey while ants are unleashed on her. Bobby escapes from the compound (managing to dispatch two pursuers in a patch of quicksand), and in a very perfunctory montage gets revenge on everyone who has tormented him – dad and Janis, and the gang of rapists – before returning to the compound with a bag of severed heads which he sets down on Simon’s breakfast table in order to prove that he really is worthy of Satan’s love. After all he has been through, he finds a happy ending in the cult … and in Sherry’s bed.

What does it all mean? Who knows? Middle class suburbia is rife with sexual discomfort; gay men are predatory rapists; but for those with determination Satanism offers a safe haven.

Satan’s Children looks surprisingly good in a 2K scan of the only surviving 35mm print. The disk includes a commentary from queer film historian Elizabeth Purchell and Bret Berg, a reunion Q&A from 2014, a 1970 TV program about the occult, and a couple of short films, the animated Satan in Church and Boys Beware, an educational short made in Pasadena during the ’70s warning boys about the danger of sexual predators.

Pathogen (Emily Hagins, 2006)

Pathogen (2006) is interesting for very different reasons. Rather than being made by jaded professionals, this zombie movie was written and directed by a twelve-year-old girl. In fact, Emily Hagins apparently began writing her script when she was ten, displaying a precociousness which is both admirable and unsettling. She also did the camerawork and editing.

Carelessness at a research lab leads to an experimental virus/microchip leaking into a town’s water supply, transforming the population into zombies. A group of middle-school kids gradually figure out what’s going on and fight to survive, while the adults remain ineffectual. Although performances are somewhat awkward, Hagins constructs scenes with some sense of drama, varying camera angles and cross-cutting to built tension. She also displays a natural ability to use locations effectively – her school, a supermarket for the climactic action, and the suburban streets and homes of her neighbourhood. While the movie remains fairly rudimentary (unsurprisingly), it’s undeniably ambitious and works on its own terms.

And in this case, AGFA provides substantial extras. There’s a commentary track with Hagins looking back on the experience, a brief cast-and-crew Q&A after the 2006 premiere, a short film Hagins made the following year, and most surprisingly Zombie Girl: The Movie (2009), a feature-length making-of documentary by Justin Johnson, Aaron Marshall and Erik Mauck. That another crew followed Hagins during the long production process seems almost as implausible as the fact that she managed to make her movie; that the documentary is as revealing as it is makes it occasionally uncomfortable to watch.

As precocious as she was, Hagins was still nonetheless a twelve-year-old middle-school kid for whom the sustained discipline required to make a movie – a feature! – was hard to maintain. What emerges is the enormous amount of support she had from her parents, particularly her mother Megan, who makes a heroic effort to allow Emily to control the project while functioning as production manager, assistant director and makeup effects artist. Megan’s sense of frustration is shared by the viewer as shoot days are poorly planned, personnel and equipment not ready when needed. As the shoot drags on, with Emily displaying the limits of a twelve-year-old’s sense of responsibility, it becomes more and more remarkable that the project reaches completion – editing takes a long time, with re-shoots necessary to make scenes work – and one’s admiration for Megan’s patience and commitment grows. All creative kids should have this kind of support.

*

We’re All Going to the World’s Fair

(Jane Schoenbrun, 2021)

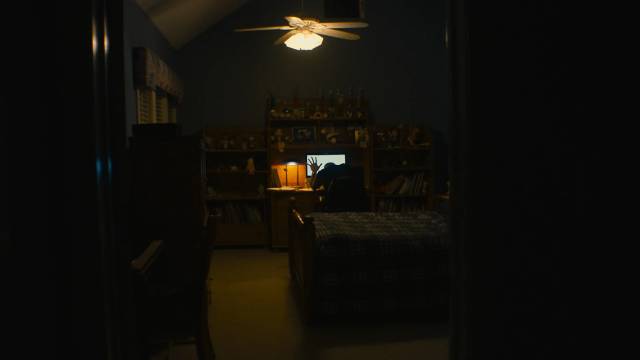

Internet horror is a smaller genre niche than found-footage, and similarly has some built-in issues. With found-footage, the big one is why do people keep filming when things get difficult and dangerous; with the Internet, it’s the inherently passive nature of sitting alone staring at a screen. For better or worse, Jane Schoenbrun takes that limitation as the central subject of We’re All Going to the World’s Fair (2021), a movie that confronts the paradox of on-line communities which create an illusion of connection and shared experience for people who are alone and unconnected in real life.

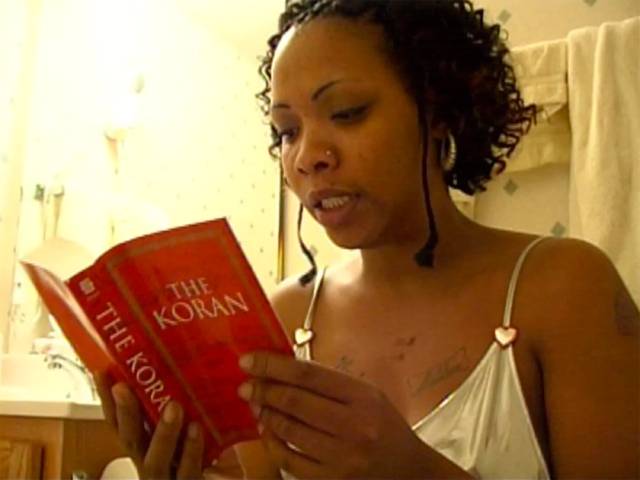

Like most Internet horror movies, the narrative posits a kind of virtual infection – there appears to be a deep societal anxiety about the malevolence embedded in the Internet, suggesting that technology has far outstripped our psychological capacity for grasping radical changes in the way we connect with other people. In Schoenbrun’s somewhat oblique treatment, a teenage girl takes the “world’s fair challenge” in order to become part of an on-line community. From what we see, she has no friends and feels alienated from her family (we never see her parents, but just once hear her father yell up the stairs for her to turn down the volume in the middle of the night). The “challenge” is a typical urban legend kind of thing: by repeating the phrase “I want to go to the world’s fair” three times while cutting her finger and smearing blood on her computer screen, she will supposedly initiate some radical change in her life.

Other people who have taken the challenge post videos documenting what is happening to them, a variety of physical and psychological transformations. These changes are as random and inexplicable as the challenge itself. The girl, Casey (Anna Cobb), posts videos of her own as she waits for something to happen, including live-streaming herself as she sleeps. Nothing much seems to happen, though as Schoenbrun holds static shots until they become tedious, then uncomfortable, we grow uneasy, expecting something to happen – and when something minor and apparently not very significant does occur, it has an impact because we’ve been primed to react.

After posting a couple of videos, Casey receives a message from someone calling themselves JLB, expressing concern for her safety and well-being, and urging her to post more so that her progress can be monitored. She has no way of knowing who this contact is from, nor what their motives are, though by now it’s logical to assume that someone on-line asking a teenage girl to post more videos of herself is probably a creep. But for Casey this may be an expression of the connection she was searching for when she took the challenge, someone drawing her deeper into the community.

Although we are soon introduced to JLB, it remains impossible to know what his motives are. An older man rattling around in a large house, he seems as lonely and alienated as Casey; perhaps he’s genuinely concerned, perhaps he is trying to groom her. None of what follows taking the challenge really changes anything. There’s no way to know whether any of the claims of transformation are genuine, no actual connections made with other members of this community, with the paradoxical effect of increasing Casey’s alienation – she finally admits that her own claims of transformation have been invented to justify her membership in the community. The nature of the Internet makes it impossible to distinguish between the real and the merely performative.

In embodying Casey’s disconnected state, Schoenbrun courts viewer boredom and irritation. The film has a cool detachment which, although there are some moments which are genuinely unsettling, makes it more of a conceptual argument than an emotionally engaging horror movie. What it does have, though, is a remarkable central performance from Cobb, whose large eyes and doll-like features convey a chilling lack of affect. The long static opening shot of Casey in her bedroom, staring directly into the camera, being recorded by her computer as she takes the “challenge”, establishes a mood and tone which carries the film a long way – although she seems self-conscious, a little nervous, not quite believing in what she’s doing, we sense a deep, unsettling absence within her willingness to embrace potential horror rather than remain in the emotional vacuum in which she finds herself.

Digitally shot, with bleak wintry landscapes on the edges of an unnamed town the only alternative to Casey’s bedroom, the film looks very good on Utopia’s Blu-ray. There are some deleted sequences, a couple of festival Q&As, a commentary with Schoenbrun and Cobb, and a long discussion between Schoenbrun and Dr. Eliza Steinbock focusing on issues of gender.

*

Out of Order (Carl Shenkel, 1984)

Compared to the rest of the movies mentioned here, Carl Shenkel’s Out of Order (Abwärts, 1984) is a conventional thriller. Well-crafted but cliched, it doesn’t offer any surprises, but it does go through its generic paces in a satisfying way. It’s Friday evening and the last four people in an office building are heading home – until the elevator stalls between floors and they’re unable to attract the attention of the security guard in the lobby.

There’s smug businessman Jörg (Götz George) and his former lover Marion (Renée Soutendijk), who now treats him with disdain bordering on contempt. There’s cocky delivery man Pit (Hannes Jaenicke), who takes an immediate dislike to Jörg, and an older office worker named Gössmann (Wolfgang Kieling), who clings suspiciously tightly to his briefcase. It doesn’t take long for frustration and claustrophobia to cause everyone to get on each other’s nerves. Marion sees an opportunity to provoke Jörg by openly flirting with Pit, who’s happy to respond. When the two men decide it’s time to climb up through the hatch and try to reach a door above the elevator, the sexual and class tension makes things dangerous.

These character conflicts are fairly formulaic – the kind of thing you find in most disaster movies – but Shenkel and his cinematographer Jacques Steyn make the most out of the small featureless box of the elevator car and the shaft, the latter being full of dangers. The sequences with Jörg and Pit up on top, risking their necks while complicating their efforts to escape with their immature masculine posturing over Marion, are lit, shot and edited for maximum tension. As thinly written as the characters are, the cast manage to make it all work, raising the stakes. Strangely, given the centrality of the Jörg-Marion-Pit triangle, the almost silent Gössmann manages to make more of an impression as we learn that this office drone has stolen a lot of cash from his employer and is planning to run away and make a new life for himself.

Subkultur’s dual-format 4K UHD/Blu-ray was scanned from the original 35mm camera negative and has an excellent image which makes the most of the dimly-lit elevator and even darker shaft, with a lot of detail adding to the film’s visceral quality. There are interviews with Jaenicke and Steyn and a slightly longer alternate cut which uses standard definition inserts to extend some scenes.

Comments

While I wouldn’t consider Pathogen a “good” movie, I found myself constantly forgiving the flaws, knowing it was made by a 12 year old (If I was a school aged peer, I would have been completely amazed!). That being said, I did appreciate her perspective taken on the genre, as it displayed familiar scenarios in a different light, for example (spoiler!): The main character having to kill her best friend – uncommon yet impressive character maturity? Or an undeveloped emotional understanding of the situation?

All in all, the ideas were still cohesive and comprehensive – I’ve seen much worse by “competent” adults – and it being made out of passion rather than to cash-in made it that much more admirable.

Given all of the above, I suppose it IS a good movie!

Hagins actually continued making movies, including a couple more features in her teens, which is impressive, and seems to have received generally positive reviews. I’ll have to seek some of them out to see how her talent has developed. She has a new horror-comedy out this year.