World Cinema Project 4: Criterion Blu-ray review

The work of the Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project doesn’t simply make available a wide range of movies from many different cultures; it serves as a reminder of the role accident and contingency play in what we know about cinema history. More films have been lost than survive and at times it seems almost miraculous that we can regain access to something which had seemingly vanished. Sometimes the history of the film is as fascinating as its creative achievement.

Criterion’s fourth set in their on-going series of WCP releases gathers six more titles from five continents and three decades (the 1930s, ’40s and ’70s) which reveal complex cultural and political undercurrents in very different societies, and various forms of stylistic experimentation rooted in both local experience and outside influences. There are two features from post-colonial Africa which illuminate the complex effects of tradition distorted by colonial influences; a South American movie which also deals with colonialism and the exploitation of labour; a pre-war Hungarian feature about two women struggling to survive in a city towards the end of the Depression; an Indian film exploring myth and the politics of Independence and Partition through music and dance; and a pre-revolutionary film from Iran which uses melodrama as a metaphor for the nation’s transition from feudalism to modernity.

*

Sambizanga (Sarah Maldoror, 1972)

While the colonization of Africa was carried out by a number of European nations, it seems that the emergence of African cinema has been most closely tied to France, both in terms of financial support and production personnel and facilities. Sarah Maldoror, born in France to a father from Guadaloupe and a French mother, trained in film in Moscow (where she crossed paths with Ousmane Sembene) and gained experience as an assistant on Gillo Pontecorvo’s Battle of Algiers (1966) before beginning her own directing career. Her choice to focus on African experience wasn’t rooted in a particular national identity and she made films (mostly documentary) in many countries on the continent.

Her first film, the short Monagambééé (1968), was based on a story by Angolan writer Jose Luandino Vieira, and dealt with a woman whose husband was being held in prison by the Portuguese colonial authorities, a situation expanded on in her first feature, also adapted from the work of Luandino Vieira. Actually, Sambizanga (1972) would have been Maldoror’s second feature, the first, Guns for Banta (1970), having been abandoned unfinished, at least in part because her backers balked at her focus on women’s experience in the armed resistance to Portuguese control of Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde.

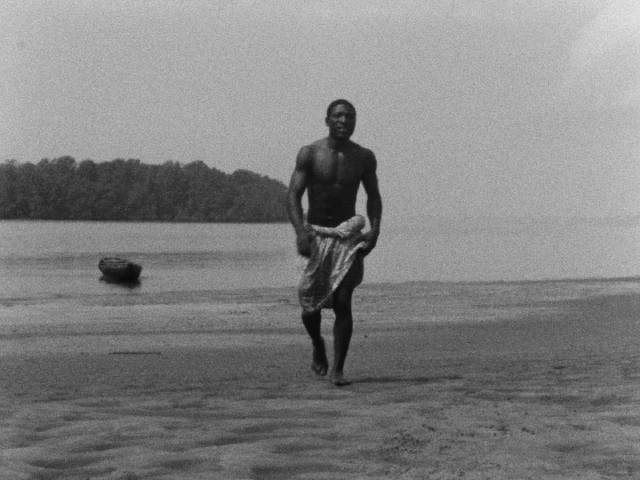

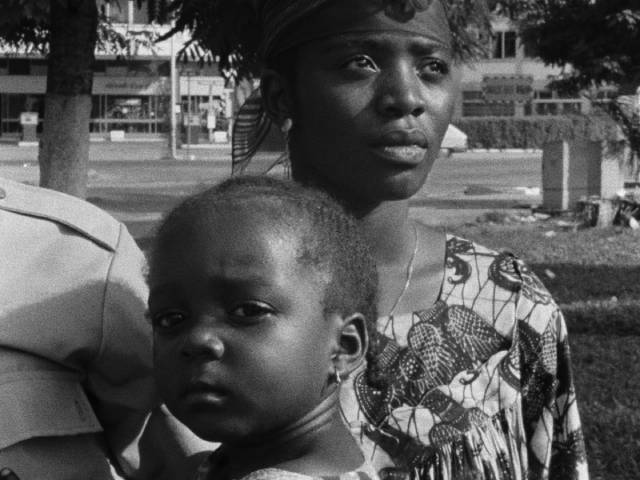

Sambizanga also centres on the experience of a woman, this time in the days leading up to an uprising in Angola on February 4, 1961. Maria (Elisa Andrade) is the wife of tractor driver Domingos Xavier (Domingos de Oliveira), who is involved in the resistance against the colonial authorities. When Domingos is arrested by the secret police and taken to a prison in Luanda, Maria sets out on foot with her baby on her back to try to find him. The film alternates between her journey and the increasingly brutal interrogations inside the prison. As Domingos stoically refuses to submit, members of the resistance are set in motion in the town; a boy saw Domingos being delivered to the prison and reported to his grandfather, who in turn reported to others who attempt to identify the prisoner in order to gauge the risk to their organization.

As Maria walks from police station to police station and prison to prison, she is treated with harsh contempt and disdain by the authorities, but is greeted with sympathy and support by people along the way. She is fed and given a place to rest, while other women take her baby and breast feed him to relieve her. Maldoror builds a portrait of a community unified against colonial oppression, with women playing a crucial part in the resistance, providing a social foundation on which armed action rests. The authorities attack the men they see as a militant threat while remaining unaware of the depth of the resistance which permeates the society they oppress and exploit.

Sambizanga balances the harshness of the situation with the tenderness shown by the African characters to one another, and Maldoror expresses the positive qualities of the social bonds – both within the family and among the network of strangers engaged in communal resistance – with images which combine a documentary precision with aesthetic beauty (something which she was criticized for). These visual qualities provide a positive counterweight to the brutality of the colonial forces, which she doesn’t dwell on, although what she does show is sufficient to make her emotional and political points. Domingos’ stoic silence and the impersonal violence of the police convey the essence of the colonial system, his humanity facing their casual inhumanity. The sequence in which his dead body is dragged into a crowded cell where the other prisoners tenderly clean the blood from his face and sing a song with the refrain “Let us never forget him” signals the strength which will ultimately defeat the oppressors … even though it would take years of resistance and a Leftist coup in Portugal in 1974 for independence to be finally granted.

*

Muna Moto (Dikongué-Pipa, 1975)

The impact of colonialism also hangs over Dikongué-Pipa‘s Muna Moto (1975), although the film focuses on the corruption of native culture rather than the overt politics of subjugation. The film tells a smaller, more personal story which the viewer must piece together from an initially confusing frame and a series of flashbacks which gradually reveal the characters and the conflicts between tradition and personal experience which produce an intimate tragedy.

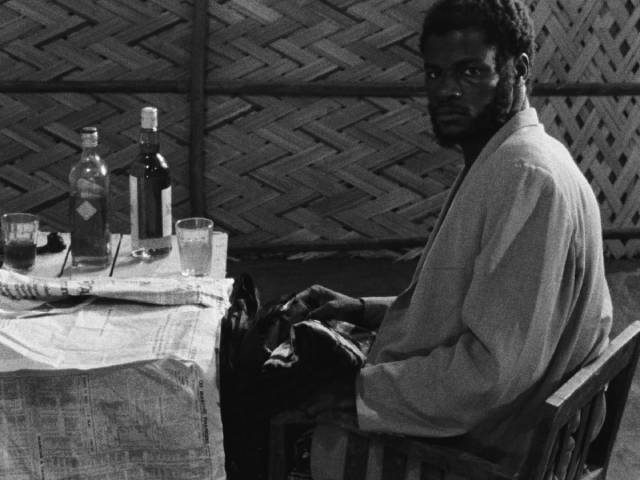

During an annual festival in Cameroon, a man we will come to know as Ngando (David Endene) searches through the crowd. Eventually he comes across a woman with a young child. He takes the child and runs, pursued by the desperate woman and members of the crowd, eventually stopping in a courtyard by a well – he holds everyone at bay, seeming to threaten to drop the child into the opening. During this standoff, the film circles back to tell the story of Ngando, Ndomé (Arlette Din Bell) and the child.

Ngando and Ndomé are in love and betrothed, but they can’t marry until he gives her family the dowry. Once a token, this is now prohibitively inflated due to the infection of materialism brought by colonialism. Ngando struggles to raise money through various jobs, but nothing really pays – fishing has been decimated by foreign trawlers, cutting down trees is backbreaking and unprofitable… And so Ngando asks his uncle (Abia Moukoko) to help. This uncle is head of the family since Ngando’s father died; he has taken Ngando’s mother as his fifth wife and now controls the family’s wealth.

But, despite all his wives, this uncle is childless. Unable to acknowledge his own impotence, he blames the wives (who openly disdain him) and decides that Ndomé, being a virgin, can give him a child … so he pays the dowry for himself, not for Ngando. Trapped, Ndomé convinces Ngando to take her virginity, although this violates tradition. She becomes pregnant, but the uncle goes through with the marriage and claims the child as his own. Ngando continues to live with the family, producing intolerable tensions since everyone knows that he is the father of the uncle’s child. That child is the one he grabs during the festival, but the gesture proves futile – whatever his and Ndomé’s feelings for one another, the situation is beyond their ability to change and Ngando has to relinquish his daughter and is taken away to prison by the police.

Muna Moto (The Child of Another) combines a love story with an ethnographic study of Cameroonian culture, damaged by colonialism and fraught with conflicts between tradition and individual desires. The striking black-and-white imagery has a documentary quality, while the performances convey the intense emotions of the broken romance, with the characters frequently looking directly into the camera to demand recognition of those emotions.

*

Prisoners of the Earth (Mario Soffici, 1939)

Set in 1915, Mario Soffici’s Prisioneros de la Tierra (Prisoners of the Earth, 1939) carries the deleterious effects of colonialism to another continent with a story of exploited workers known as mensús in a remote area of Argentina. The brutal owner of a yerba maté plantation treats indentured labour little better than slaves, binding poor men to contracts which, rather than paying them, place them in debt with charges for transportation, food and lodging which exceed the meagre wages he ostensibly pays. In addition, malaria and other diseases claim many lives.

Esteban Podeley (Angel Magaña) knows that the odds are stacked against him, but he signs up anyway. Köhner (Francisco Petrone) immediately marks him as a troublemaker and Esteban finds himself tied to a mast on the boat even before they reach the plantation. This punishment attracts the attention of Chinita (Elisa Galvé), the daughter of Dr. Else (Raúl De Lange), who has been contracted by Köhner to deal with the sickness decimating his workers. When Chinita gives Esteban water, Köhner’s dislike is intensified because he’s attracted to the young woman himself.

As the hard work of harvesting the yerba leaves gets underway, a romance develops between Esteban and Chinita, though her attention is preoccupied with trying to manage her alcoholic father, whose drunkenness eventually results in the death of several workers when the medicine he concocts turns out to be poisonous. Soffici blends a kind of neorealism with romantic melodrama, the various personal tensions driving the underlying economic and social injustices inexorably towards a tragic conclusion. Nonetheless, despite their generic roles in the narrative, there’s some moral complexity to the characters – we even gain some sympathy and insight into Köhner, who is himself trapped in this inhospitable landscape, homesick for his native Germany, while the rebellious Esteban eventually erupts in an act of savage violence, fuelled by both the oppression of the workers and the romantic tension. The latter, in fact, leads him finally to a gesture which is purely self-destructive and serves no useful purpose in the larger social conflict.

Esteban provides a bridge between the two narrative registers, while the other characters tend to fall more clearly on one side or the other. Köhner and his brutal overseers stand for the oppressive economic system which exploits the workers, while Dr. Else and Chinita are closer to melodramatic stereotypes – the doctor comes closest to caricature in the extremes of his alcoholism, while his daughter has the innocent naivety of a romantic ingenue who remains unaware of the risks posed by the competition for her affections.

Although Prisoners of the Earth held a recognized position of importance in Argentine cinema, it was believed to survive only in two very battered 16mm prints until a search begun in 2008 eventually unearthed two 35mm prints – one at the Cinematheque francaise, the other at the National Film Archive in Prague – which formed the basis of this impressive restoration, which makes fully apparent the quality of Pablo Tabernero’s evocative cinematography.

*

Two Girls on the Street (André De Toth, 1939)

Before escaping Europe at the start of the Second World War and landing in Hollywood where he most notably made a distinctive series of westerns and films noirs, André De Toth directed five features in 1939. Although he dismissed these films as rubbish, the one included here is well-crafted and surprising, particularly given the rugged persona De Toth projected through his work in the States.

Two Girls on the Street (1939) gives a noirish quality to its depiction of female friendship and rivalry. In the opening scene, Kártély Gyöngyi (Maria Tasnadi Fekete) causes a scene at a celebration marking the engagement of her lover to another woman; the scandal leads to her being driven from her provincial home and obtaining an abortion. Disowned by her parents, she makes a living in the city by playing violin in an all-girl band. Torma Vica (Bella Bordy) has also left home, but she lacks any real skills, taking a labouring job on a building site. Having received permission to sleep in the site’s tool shed, she strikes up a conversation with the project’s architect, Csiszár István (Andor Ajtay), who sees her shadow through a doorway as she undresses and attempts to assault her. As she flees in the rain, she encounters Gyöngyi who takes her home.

Vica seems young and naive and Gyöngyi is initially protectively maternal. Their relationship gradually evolves, with more than a suggestion of physical and romantic involvement. And yet the narrative becomes centred on their rivalry for none other than István, whom we have no reason to trust as a romantic lead given that early scene of attempted rape. It’s almost as if convention required a certain structure which ill fits the characters, but the film’s real interest lies in the relationship of the two women and the ways in which they provide mutual support, emotionally and economically, as they make their way in a big city which provides few accommodations for single women.

Although the romantic narrative may be problematic, De Toth’s work is atmospheric and expressive, using a moving camera and distinctive framing to add thematic depth and dramatic nuance which at times seems to undermine the conventional intent of the script – with Gyöngyi embarked on a successful musical career and Vica finally paired with István, the two women each going their own way, the final images on a construction site, with Vica no longer a lowly worker but rather the architect’s partner, suggest that she has achieved what society deems the fulfillment of a woman’s role, but in light of all we’ve witnessed this ending lacks the emotional satisfactions of the relationship shared by the two women.

*

Kalpana (Uday Shankar, 1948)

Given cultural differences, it’s inevitable that without direct experience a viewer will miss something when watching a movie from elsewhere. This was true with the last two films in this set perhaps more than with the others. This is where disk extras and the accompanying booklet of essays are helpful. Kalpana (1948) weaves so much myth and politics into its fabric of music and dance that I definitely needed some guidance.

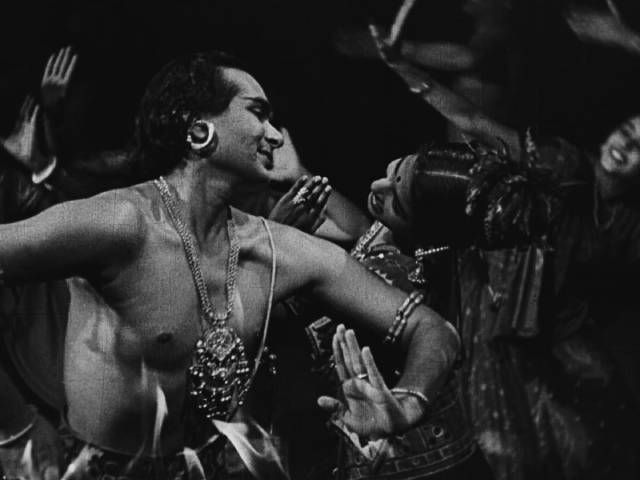

A long, seemingly slight narrative supporting big, elaborate musical numbers, Kalpana suggests the roots of Bollywood, but the film had a complicated history which saw it all but disappear soon after its release. The production was driven by the passion of Uday Shankar, the writer, producer, director, choreographer and star, whose only film it was, filling it with his mission to forge a national identity for the newly independent India.

Shankar (older brother of musician Ravi Shankar) was a hugely influential dancer with an international reputation, his work combining traditional Indian forms with western ballet and modern dance. Since the 1920s, he had been proselytizing the value of dance, establishing an academy in the foothills of the Himalayas. The film was an extension of that project, made at a critical time – it was released just a year after India became independent, amidst the chaos of partition which established the rivalry between India and Pakistan which still continues. Shankar saw the potential for a new identity rooted in tradition but open to change, and he attempted to express this in his movie.

Beginning with his character, the film director Udayan, pitching the idea for the movie to an unreceptive producer, the main body of Kalpana presents his vision, taking place in an imaginary space rooted in biographical details but liberated from the limitations of reality. Young Udayan (Farman Ali) wants nothing more than to dance, dressing in girl’s clothes and performing on a makeshift stage for other children, but it seems that he has been betrayed by a girl named Uma (Begam Zamarudh) and he is beaten by his teacher for this unseemly display.

Despite his harsh childhood, he grows up to be a successful dancer who starts his own academy … eventually meeting and falling in love with a woman he doesn’t initially realize is the now-adult Uma (Amala Uday Shankar, the director’s wife). This is the slender thread on which the film hangs its numerous increasingly elaborate musical numbers. Shankar displays not only his talents as a choreographer, but also an impressive grasp of the possibilities for expanding dance through cinematic means – camerawork, editing, and the deconstruction and reconstruction of movement through optical effects which combine individual elements into something wholly new. Many of these sequences refer back to the expressive potential of silent movies – in one sequence explicitly recalling Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1926) with its depiction of bodies and machinery intertwined.

Many of the numbers refer to the myths and religion on which Indian culture and identity rest, these traditions brought into the present by the technology of cinema, renewed and blended with other influences. Ironically, as the film returns to the framing sequence with Udayan kicked out by the unimpressed producer, it ends with the visionary filmmaker lamenting the lack of vision in his newly formed nation … a prophetic moment given not only that Kalpana itself represented an inspiration not followed by the new country’s nascent film industry, but also in the failure of India to embrace Shankar’s utopian socialist vision for his society.

*

Chess of the Wind (Mohammad Reza Aslani, 1976)

Made just three years before the Iranian revolution which overthrew the Shah and established the Islamic state, Mohammad Reza Aslani’s Chess of the Wind (1979) is quite unlike the more neorealist films more generally associated with Iranian cinema. A lushly colourful melodrama about a wealthy family in decline, I again needed the supplements to understand the narrative’s themes and undercurrents. With little obvious reference to the world outside their gated mansion, I didn’t realize that the family’s story embodied a metaphor for Iran’s transition from feudalism to modernity in the 1920s; I read it instead as something like a Sirkian meditation on the self-immolation of a bourgeois family crushed by the weight of its various members’ weaknesses.

With the recent death of a matriarch, the members of an aristocratic family vie for control of the estate. These include the matriarch’s husband, Haji Amou (Mohamad Ali Keshavarz); her daughter, Lady Aghdas (Fakhri Khorvash); and her two nephews, Ramazan (Akbar Zanjanpour) and Shaban (Shahram Golchin). As conflicts escalate, another character gradually increases in significance, the servant Kanizak (Shohreh Aghdashlou).

The boorish, authoritarian Haji Amou dominates the household using religion as his means and justification, while Lady Aghdas simmers with a resentment so powerful that she seems to be going mad – confined to a wheelchair, requiring others to push her about the house, she shows open contempt for Amou while tearing up books and smashing things. The two nephews are filled with bourgeois ambition, while Kanizak moves fluidly among her employers, engaging with both men and women sexually.

The jockeying for power devolves into a series of killings which decimate the family, ultimately leaving Kanizak the survivor who finally opens the gates and escapes what has become a mausoleum for a way of life no longer viable.

With its rich colour palette and dense production design, the film has an oppressive tone which is only intermittently relieved as Aslani cuts to a fountain outside where local women gather to do their laundry and gossip, commenting on the family and what’s going on inside the mansion. In Hitchcockian fashion, the interior is dominated by an imposing staircase which frames much of the action (and violence). For someone more familiar with the poetic naturalism of Abbas Kiarostami or Mohsen Makhmalbaf, Chess of the Wind has a surprisingly theatrical quality, its critique of class more literary than political – though this impression might well be due to unfamiliarity with the context within which it was made.

The account of the film’s production and reception given in The Majnoun and the Wind (2022), a one-hour documentary by Aslani’s daughter, Gita Aslani Shahrestani, included on the disk, suggests that it was dangerously transgressive for those in authority in the years before the revolution. Its screenings at the 1976 Tehran International Film Festival were sabotaged – reels were run out of order and the projector lamp dimmed, rendering it virtually unintelligible and triggering hostile reviews; it was then suppressed by the post-revolution government, disappearing except for very poor quality video copies.

The rediscovery of Aslani’s film provides the set with its most remarkable story. A lost film, its resurrection seems utterly implausible. In 2014, the filmmaker’s son was scouring through the stalls of an antique market when he came across a pile of film cans in a corner which turned out to be the original negative and sound reels, which he immediately bought and managed to ship out of the country. The coincidence seems absurd, and yet one can’t help but hope that such things mean there’s a chance other lost films might still resurface.

*

The disks

Criterion’s set, like the previous volumes, contains the six features on three Blu-ray disks and six DVDs. Naturally, given the different ages and individual histories of the features, quality varies slightly, but is generally excellent. Sambizanga, Chess of the Wind and Muna Moto were all scanned in 4K from the original camera negatives, while both Two Girls on the Street and Kalpana were scanned in 2K from, respectively, the camera negative and a duplicate negative. Prisoners of the Earth was scanned in 4K from two archival prints.

The supplements

Each movie gets a brief 2-3 minute introduction from project founder Martin Scorsese and a featurette providing some history and context. These range from eleven minutes of interview clips from André De Toth (Two Girls on the Street) to 20-25 minutes with archivists, film historians and others (Muna Moto, Prisoners of the Earth, Sambizanga, Kalpana) to, most substantially, the 53-minute documentary about Chess of the Wind.

The 72-page booklet includes an introduction by the set’s producer plus an essay on each film and notes on the restorations.

No doubt it’s unreasonable, but given the quality of these World Cinema Project sets, I wish they would be released more frequently. There must be so much more out there to explore.

Comments