George A. Romero’s The Amusement Park (1975)

I should perhaps mention that this review marks the twelfth anniversary of this blog, and the 832nd post, with close to three-thousand movies reviewed, or at least commented on. It’s hard to believe that I’ve kept this up, posting at least once a week, sometimes twice, without a single break. Somewhere above a million-and-a-half words. I guess that counts as an obsession rather than a hobby or pastime. I hope someone out there has enjoyed reading my thoughts as much as I’ve enjoyed writing them down…

*

It’s not often that a previously unknown work surfaces years after a filmmaker’s death. Not a lost film whose elements have disappeared, but one which was neglected by the filmmaker himself because he didn’t consider it a significant part of his work. And yet here is a substantial movie made by George A. Romero in 1975, between The Crazies (1973) and Martin (1976). Despite having completed four features by that point, Romero’s feature career wasn’t yet on a firm footing; he was still making a living on commercials and industrial films at The Latent Image, his company in Pittsburgh, which had enabled him to produce and direct Night of The Living Dead (1968), There’s Always Vanilla (1971), Season of the Witch (1972) and The Crazies between commissioned work.

Through 1973 and ’74 he had branched out into television documentaries, then in 1975 The Latent Image were commissioned by Lutheran Services, a social work organization concerned about the plight of the elderly, to make a film highlighting the challenges faced by that neglected segment of society. Romero was dismissive of the resulting 54-minute film because it was one of the company’s jobs-for-hire, scripted not by himself (as most of his features were) but by Walton Cook, with whom he had previously worked on an episode of his documentary series The Winners (1973-74). And yet it was made in collaboration with a number of key personnel from the previous features, including associate producer Richard P. Rubinstein, cinematographer S. William Hinzman, sound recording and camera assistant Michael Gornick (who would shoot all the features between Martin and Day of the Dead [1985]).

What’s really fascinating about The Amusement Park (1975) is the way in which Romero transformed what could have been a dry educational project into something seemingly much more personal. You have to wonder whether the Lutherans were familiar with his work beyond the Latent Image commercials, because what they ended up with was a horror movie with many of the hallmarks of Romero’s features. One of the things which first drew me to Romero’s work, not surprisingly given my own later career, was his skill as an editor – his direction and camerawork were obviously dictated to a large degree by how he intended to construct scenes in the editing room, each shot a discreet element designed to fit tightly into a larger pattern which not only gave the whole a sense of relentless momentum but also guided the constantly shifting emotional flow. That skill is on full display in The Amusement Park.

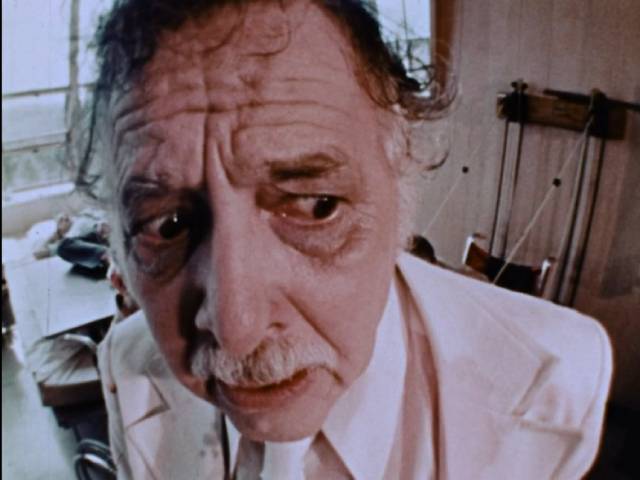

The film is framed with a fairly conventional direct address to the audience by actor Lincoln Maazel, already in his early 70s and a year away from his very different role as Tata Cuda in Martin. Walking through the empty, desolate pathways of a seemingly abandoned amusement park (a location donated by owners hoping to boost business), Maazel speaks about the challenges faced by the elderly, about loneliness and deprivation, almost lulling us into expecting that lecture about what needs to be done … but the location itself creates a subtle sense of anxiety which works against convention.

As he wraps up his introduction, the screen goes white and the camera pulls back from a closed door in a featureless white room to reveal Maazel, dressed in a white suit, sitting desolately on a chair, his face cut and bruised, his clothes rumpled and dirty, his expression dazed and confused. The door opens and Maazel, wearing the same suit but gleamingly pristine, enters. He expresses concern, asks if he can help but receives only groans of despair in response. He finally turns away, opens the door and steps into the busy midway.

That midway in the active amusement park serves as both a realistic setting and a metaphor for a fast-paced society with little time for or interest in an elderly man who moves to a different rhythm. Maazel undergoes a series of encounters which reflect the impatience and disdain of people who obviously think his age means he’s somehow deficient. He’s taken advantage of, robbed, dismissed and eventually subjected to physical violence. Making use of the various park attractions the film presents a series of scenarios to illustrate prejudice and the exclusion of the elderly.

Initially cheerful and engaged, Maazel is largely ignored by the swirling crowds. He goes on the rollercoaster; he gets on the miniature train … someone apparently dies during the ride, but everyone is too busy to pay any attention. He goes on the bumper cars and witnesses a crash; an elderly couple rear-end a man (Romero himself in an amusing cameo) when he fails to signal his turn properly. Maazel offers himself as a witness to exonerate the elderly couple, but he’s dismissed by the cop because he wasn’t wearing the glasses his license requires. He tries to have lunch, but is initially ignored by the waiter who is busy with a wealthy patron; the rich man, annoyed by Maazel and a group of hungry poor people watching him, has the staff turn his table so his back is to the crowd. When Maazel offers to share his meal with the hungry people, staff are outraged and a small food riot occurs.

Sitting on a bench with a snack, he calls over a group of playing children only to have a man yell at him for being a “pervert”. Shunted into an exhibit, he finds himself inside a physiotherapy unit where elderly people are being treated and using the exercise devices, put on display like freaks. A young couple go into a fortune teller’s tent and he watches, smiling, as they insist on being told the honest truth about their future together. The fortune teller conjures up a vision of desperate old age, with the woman trying to summon aid for her sick, probably dying husband. Fleeing in horror, the young man sees Maazel and rushes to assault him as if trying to violently banish the very idea of growing old.

Battered and confused, Maazel is called over by a young girl picnicking with her family; she asks him to read to her from her story book, a moment of connection and kindness which is interrupted before he can finish the story as the mother packs everything away. Left on the grass, he breaks down and cries. When he looks up again, the park is deserted; as he wanders, three bikers roll up and viciously beat him, taking whatever meagre possessions remain in his pockets, and he finally finds his way to the white room and collapses on a chair, bloody, dirty and exhausted. At which point, dressed in his pristine white suit, he again enters and asks his injured self if he needs help, the cycle beginning to repeat itself.

The Amusement Park is dark, pessimistic and unsentimental in its presentation of a society which discards those who supposedly no longer occupy a productive place in its materialistic activities. It’s difficult to imagine how it might have been received by charitable-minded audiences, though Michael Gornick in his commentary mentions that it circulated for several years before eventually being retired. Disconnected from its original educational purpose, it can now be viewed from the perspective of Romero’s overall body of work, within which it echoes a number of familiar themes and techniques.

Tonally, the insensitive crowd, too preoccupied with their own pursuit of amusement to notice the elderly man trying to engage with them, is reminiscent of the living dead and the murderous townspeople in The Crazies, an undifferentiated horde which sweeps away not simply individuals who don’t conform to the group but individuality itself. Despite being surrounded by so many, the elderly man is alone and isolated, his sense of himself relentlessly broken down until he sinks into catatonic despair. Considering that the project is really an extended PSA, Lincoln Maazel gives a performance worthy of a feature, detailed and expressive as it evolves through various emotional states from an openness which makes him vulnerable through confusion and fear to an eventual shutting down.

Romero constructs the film with a kind of furious montage, cutting together multiple angles so rapidly that the audience itself becomes as ungrounded as the elderly man, confused and disoriented. And yet there’s a control and precision to his editing which is very different from the kind of cutting all too common in movies made with digital tools; this is not constant movement for its own sake, a compulsion to distract, but the careful control of a deliberately constructed psychological space designed to put the viewer into the old man’s state of mind – the use of technique to create empathy.

The setting, the rundown attractions of the park, undermine the illusion of a vibrant and purposeful society. At times, it’s reminiscent of the decaying pavilion in Herk Harvey’s Carnival of Souls (1962), itself an influence on Romero’s depiction of the living dead. This world is haunted by dislocation and anxiety and a sense of loss. In some ways, Romero seems to have taken the opportunity of this commissioned work to experiment with techniques which could be used to enrich the features which followed. For all their interesting qualities and impressive accomplishments, the first four features were apprentice works and The Amusement Park shows Romero applying everything he had learned up to that point in a kind of concentrated form. Following this, he made the first of his truly mature films, Martin, followed in turn by the epic Dawn of the Dead (1989), films whose complex techniques are handled with great, and seemingly effortless, confidence.

Although Romero himself apparently didn’t take the film seriously, it can be seen as a significant piece in his development as a filmmaker, an experiment which transforms a commercial assignment into an opportunity to delve into his own obsessions in disturbing ways – the dehumanized horde overwhelming the vulnerable individual, the materialism which destroys empathy, the random eruptions of violence. We even get those bikers, who prefigure not only the marauders of Dawn of the Dead, but also their mirror image as representatives of an anachronistic romanticism in Knightriders (1981).

*

The RLJEntertainment/Shudder Blu-ray does full justice to this rediscovered work, supplementing the restoration of the film itself with a commentary and a number of interviews which go into detail about the original production and the rediscovery and restoration. Participants include Michael Gornick (in conversation with extras-producer Michael Felsher on the commentary); Romero’s widow Suzanne Desrocher-Romero who oversaw the entire restoration via the George A. Romero Foundation; script supervisor and actor Bonnie Hinzman; artist Ryan Carr, who’s working on a graphic novel based on the film; Sandra Schulberg, whose company IndieCollect did the restoration work; and author Daniel Krauss, who completed Romero’s unfinished novel The Living Dead.

When the film resurfaced in 2017, it existed in only two very battered 16mm prints, so the restoration seen on the disk is a remarkable accomplishment, even though there are still some scratches and the colours are somewhat faded. It may not be what people have come to expect of a “4K restoration”, but given the brief glimpse we see of the unrestored image, what has been achieved is admirable, and given the rarity of the film we should be grateful no matter how compromised the quality might be.

Perhaps the most remarkable information provided about the production is that it was shot in just three days. The sheer number of set-ups providing Romero with all those angles for his rapid-fire editing is impressive, as is the handling of all the non-professional extras who make up the crowds. Although Gornick does point out where the same extras double-back and circle round through a shot to give the impression of a bigger crowd, there are numerous wide shots of the busy midway which provide the film with a sense of scale; individual performances (mostly provided by crew members – Gornick and Bonnie Hinzman, cinematographer Bill Hinzman), while portraying types, are good, while direction of the crowd itself avoids any aimless milling about. Romero obviously put as much effort into this commissioned work as he did the features, committed to the project as both professional and artist.

Although by no means a major work, The Amusement Park is a fascinating footnote to Romero’s career, illuminating a period during which his technique and interests were developing in ways which were key to the films he would make in the following decade.

Comments

Kenneth,

congrats on 12 years of posting. I’m a long time movie fan. I started out with betamax, vhs, upgraded to laserdisc then HD DVD and finally blu-ray. I can honestly say your movie reviews are fantastic. You easily could have scored a job at a top newspaper as a movie reviewer. I’ve referred your blog to many friends over the years. One of the things I really like about your blog is it introduces me to great films that I didn’t know existed.

Also, you educate the reader about the movie industry in general, which is always appreciated. I’m sure anyone who comes across your blog appreciates the high quality of your reviews.

I now read everything you post as it comes along. Very interesting and educational, even if the movies you review aren’t always entirely my cup of tea- which is rare- the review itself is a good read!

I hope you keep up the good work for as long as you are able to!

Thanks for the positive feedback, Kevin. It’s always good to get some reassurance that I’m not just talking to myself here!

One thing I forgot to mention…. the danger in reading your reviews is that it makes the reader want to buy the movie! I’m going to order a copy of The Amusement Park from amazon.

It truly sounds like a frightening look at old age. One of my favorite films is Umberto.D..

a tragic look at poverty in old age. The Amusement Park sounds like it’s a look at the degradations that can accompany old age… in classic Romero style!

Again, thanks for the efforts. Your vast interest and knowledge about movies and the movie industry in general, are on full display each and every time you post a new review.

It’s a pity I don’t get a commission!

Romero’s film has a visceral kick, but obviously it lacks the devastating emotional impact of Umberto D. – but then, it was made for very different purposes.