Two Mexican westerns from Vinegar Syndrome

Given the significant part Mexico plays in the history of the Western, it’s odd that I never gave much thought to the possibility that Mexican filmmakers might have tackled the genre. A recent Vinegar Syndrome release offers a corrective to that oversight with a pair of movies from the mid-’70s, both of which not surprisingly echo Italian and Spanish Westerns more than those from Hollywood.

Guns and Guts (Rene Cardona Jr, 1974)

Last year, Vinegar Syndrome launched a projected series with volume one of The Cardona Collection, devoted to the prolific output of Rene Cardona Jr. However, the death of Cardona’s son Rene Cardona III immediately stalled the project. However, one of Jr’s movies is included on the new double-feature disk. Shot in English, Las viboras cambian de piel aka Guns and Guts (1974) was one of many movies aimed at an international market (like the three in the previous box set); it has the feel of a spaghetti western but also obviously draws heavily on The Wild Bunch, which itself had a strong connection with Mexico.

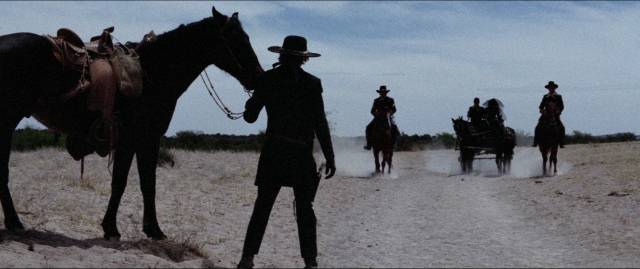

Cardona, working from a script by the incredibly prolific Spanish writer Fernando Galiana (almost two-hundred feature credits), fills the movie with genre archetypes and familiar visual elements – vast open landscapes, small western towns, an old Spanish mission as the villain’s lair; fist fights during which a lot of furniture gets smashed; and showdowns performed as a kind of ritual of masculinity – along with some very Peckinpah-esque blood splatters. If Cardona falls short of the genre’s mythic qualities, he does display an understanding of what goes into making a Western and stages all the elements effectively.

Opening with a man racing across country with a posse on his tail, Cardona gets things off to a good start. Having evaded his pursuers by ditching his horse, he walks to a ranch where he trades his gun for another horse, then rides to a town where he trades the horse for another gun… In most Westerns we don’t see this kind of thing, how a man has to haggle and sacrifice just to stay afloat. This man (Rogelio Guerra), whose name we never hear (each character is identified only as a type), has escaped from prison and is on his way to get revenge against the man who betrayed him. He meets, and makes an uneasy alliance with, another man (Pedro Armendáriz Jr.) who turns out to be on the same mission – this one is seeking revenge against the man for stealing his wife. Neither is sure they’re up to doing the job, so they hire a gunman (Jorge Rivera) who actually seems to be more interested in spending his time with multiple prostitutes than killing the man they’re looking for.

They eventually discover that this man (Quintín Bulnes) is now the sheriff of Santa Fe, living in a huge old mission surrounded by armed men. It seems impossible to get to him and the gunman betrays the pair who hired him – or so it seems, though eventually it turns out to be part of his plan to get close to the sheriff. But finally getting close to him turns out to be unsatisfying for everyone – the abandoned husband realizes that his wife (Gladys Vivas) went willingly. In Leone fashion, motives remain ambiguous and the three uneasy allies seem as likely to turn on each other as they are to attack the sheriff … but in the end, in Peckinpah fashion, they make a fatalistic decision to go back into the mission and take on a far larger, heavily armed force and Cardona pulls out all the stops with a climactic slaughter including explosions, a Gatling gun, and vast quantities of blood squibs, many exploding in slow motion in a display of futile mutual destruction.

The build-up is unevenly paced, with a mix of tension and comedy – the gunman’s obsession with his whores is exaggerated to the point of sexual slapstick, giving an excuse for plenty of nudity. But it’s punctuated with action in the form of those bar fights and one particularly shocking showdown; in a town along the way, a young man calls out the gunfighter for having killed his father. The gunfighter tries to talk his way out of the confrontation, but the young man won’t back down. Shots are fired and the young man dies one of the most painfully graphic deaths seen in any Western: the bullet hits him in the neck and arterial blood spits out rhythmically as he clutches his throat, stunned and disbelieving. He eventually collapses to the ground, struggling against the continuing loss of blood, until the gunfighter finally walks over and puts him out of his misery with another shot. It’s a nasty, brutish sequence which exposes the formalized ritual of such scenes in most movies as a romantic illusion, and for a moment it raises Guns and Guts to genre greatness.

Well shot by cinematographer Jose Ortiz Ramos (more than 250 credits over a fifty-year career), with decent performances by Rogelio Guerra, Pedro Armendáriz Jr., Jorge Rivera and Quintín Bulnes, Cardona’s Western may not be up there with the films of Leone and Peckinpah, but it fits nicely into the second tier of spaghetti westerns made in Leone’s wake.

*

in Fernando Duran Rojas’ Vibora caliente aka Hot Snake (1976)

Hot Snake (Fernando Duran Rojas, 1976)

Fernando Duran Rojas’ Vibora caliente aka Hot Snake (1976) follows a different strain of spaghetti western, those which blend western tropes with horror motifs – like Giulio Questi’s Django Kill … If You Live, Shoot! (1967) and Antonio Margheriti’s And God Said to Cain (1970). But there’s more than the suggestion of the supernatural to make this movie interesting; the narrative structure confounds expectations so you can never be quite sure where it’s going.

Duran Rojas sets a grim tone in the opening sequence. A wagon driven by a soldier, with a couple more soldiers riding escort, is carrying the coffin of a dead officer and his widow through an arid landscape. They’re stopped by an armed man who immediately guns down all the soldiers. Shifting the coffin, he pulls a strong box from its hiding place, then as an afterthought decides to rape the widow. When she resists, he kills her, then proceeds to rape her corpse. We know who the bad guy is – a thief, murderer, rapist and necrophile.

Riding into the hills this man stops at a shack occupied by a native woman named Ramona (Monica Miguel) and her silent partner who tends his horse and plays the flute as she reads the Tarot. He says his name is John Smith and a friend sent him. When she uses his real name, John Jenkins (Carlos East), he’s startled, but she calmly says that she “knows everything”.

It seems that this man Jenkins has been terrorizing the region around the desert town of Hot Snake for a while, but killing soldiers and stealing army payroll is just too much. A bounty of $5000 is put on his head and the sheriff hands the job to bounty hunter Emiliano (Eric del Castillo). He too visits Ramona, seeking information and apparently some protection from the spirits. She tells him that a man wants him dead, a blonde man who has been close to him, but not Jenkins. She tells him to beware a day with two nights.

Before taking off after Jenkins, Emiliano spends some time with the prostitute Eva (Christa Linder), whom it seems he’d like to settle down with. Then another bounty hunter named Miranda (Noé Murayama) shows up, who’s also tracking the outlaw. Emiliano sends him to see Ramona to clear off any bad luck; she performs a ceremony and gives him a coin Jenkins had tossed to her. The magic doesn’t help, because when Miranda catches up with his quarry, Jenkins kills him.

Finally setting off to do the job, Emiliano encounters various ill omens – snakes and scorpions – while a young man watches from a distance. This is Eric (Ricardo Noriega), who in a series of flashbacks is revealed to be a servant at the brothel where Emiliano visits Eva, and whom the bounty hunter enjoys humiliating in front of the woman Eric is obviously infatuated with.

Surprisingly, Emiliano quickly catches up with Jenkins and kills him easily. With the body draped across his horse, he starts the journey back to town … but then things take a turn for the macabre. After a night under the stars, Emiliano wakes to find the corpse sitting up, its eyes open, staring at him. From then on, although dead, Jenkins seems to mock his killer, eventually vanishing, only to turn up on horseback riding to attack. Emiliano empties his gun into the dead man, shaken and losing his cold-blooded self-confidence.

Unnerved, he’s no match for Eric when the young man, who has been playing mind games using Jenkins’ corpse, finally confronts him just as the moon begins to slide across the sun, turning midday into night. With both the villain and the ostensible hero dispatched, the final stretch focuses on Eric’s plan to get even with everyone who has humiliated him, but in keeping with the film’s dark tone this doesn’t end well either.

While traditional Westerns and spaghetti westerns don’t always have clear-cut heroes, they usually compensate with a strongly defined anti-hero for the audience to root for. But Hot Snake offers neither – the apparent hero Emiliano is revealed to be an arrogant jerk, the villain Jenkins is irredeemable, and Eric, who really only emerges as a character late in the narrative, is a rather pathetic figure acting out a grandiose plan to assuage his hurt feelings.

Duran Rojas invests the story with menacing atmosphere which may or may not contain actual supernatural elements – the characters seem ready to believe in spirits and evil forces, and Eric is able to use those beliefs to further his plan. Along the way, Hot Snake manages to surprise the viewer with unexpected turns which keep it from slipping into well-worn formulas.

*

Both films look very good on Vinegar Syndrome’s Blu-ray, with Hot Snake in Spanish with subtitles and Guns and Guts in English. The only extra is a fifteen-minute interview with Rene Cardona III about the production, the influences of Peckinpah and Leone, and his own childhood memories of the shoot.

Comments