Brief Notes, December Part One

Well, it’s deja vu all over again …

I recently had my second heart attack in less than two years. Luckily, once again it was “minor” – a couple of days in hospital and a second stent installed to open up another partially blocked small artery. All pretty dispiriting. Needless to say, sitting at home without a lot of energy, I’ve been watching movies … but perhaps less attentively than usual (apart from the health issue, I have to worry about lost income since I don’t have much available leave to cover my recovery time). So I’ll just jot down a few quick comments about some recent acquisitions.

101 Films

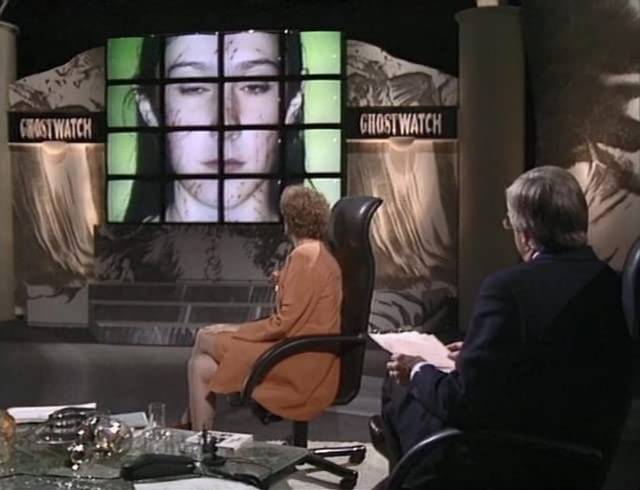

101 Films is an English company which seems to cover similar terrain to Vinegar Syndrome, Severin and Shout! Factory. They came to my notice when I bought a copy of Saul Bass’s Phase IV a month or so ago, at which time I discovered they were scheduled to release a limited edition Blu-ray of the BBC’s Ghostwatch (1992). I already had the 20-year-old BFI DVD, but it was obvious I should go for the upgrade, although the original broadcast video source would offer only limited improvement. However, the disk includes a 50-minute 30th anniversary documentary and a new commentary, in addition to the original BFI commentary, and comes in a sturdy case with a set of postcards, a booklet with a couple of essays and a short story by the show’s writer Stephen Volk, plus a reproduction of the script with director Leslie Manning’s annotations and storyboard sketches. The show itself holds up well as a recreation of all the cheesiness of British broadcast television which is gradually overwhelmed by genuine supernatural events. The use of real celebrity presenters playing themselves caused quite a backlash after Ghostwatch aired, with a lot of viewers feeling duped by the BBC … we’re so used to faked reality by now that it’s difficult to grasp fully what that violation of audience trust meant back then. In the context of the found-footage genre, though, Ghostwatch stands as a pioneering work and remains very entertaining.

Since these releases drew my attention to the 101 Films website, I ended up ordering a couple of their other titles as well.

Andrew Marton’s Crack in the World (1965) was probably the first disaster movie I ever saw and, at ten, it made a deep impression. (I had seen George Pal’s Atlantis: The Lost Continent [1961] with a catastrophic climax a few years earlier, but that was fantasy, while Marton’s movie was set in a recognizable contemporary world.) As with any disaster epic, allowances need to be made, but what matters is the air of plausibility the filmmakers manage to invest in the material, and in this regard Crack in the World holds up very well. A team of scientists and engineers working in Africa plan to puncture the planet’s core to release the minerals and energy contained in the magma, bringing the dawn of a new age for the benefit of all. Only one team member raises serious questions about the project, but he’s pushed aside and the project goes ahead… Needless to say, he was right and the puncture in the core unleashes forces which may well destroy the planet. Played with just the right note of commitment by a fine cast – Dana Andrews as the man in charge, Keiron Moore as the doubter, and Janette Scott as the woman who complicates their professional antagonism – the well-structured script by Jon Manchip White and Julian Zimel balances personal melodrama with a series of tense sequences as the scientists attempt to stop the disaster. Made in Spain by people who had worked on Samuel Bronston’s historical epics, production values are excellent, including miniatures and matte shots overseen by Eugene Lourie. It’s always nice to have childhood memories confirmed and Crack in the World holds up really well. The disk includes a commentary, but no other extras.

Something I’d never seen before and knew only by its poor reputation was William Castle’s second-last movie, Project X (1968), made the same year he produced Roman Polanski’s Rosemary’s Baby. Castle’s idiosyncratic career was on the down-slope by then, and he would only direct one more movie six years later, the even stranger Shanks (1974). Having begun as an efficient B-movie director at Columbia in the ’40s, Castle turned independent in the ’50s and created his distinctive persona as a master of marketing gimmicks, a successful strategy which made him commercially successful while paradoxically overshadowing his genuine strengths as a filmmaker. By the early ’60s, the viability of his gimmicks was declining and he began to flounder between B thrillers and comedies. It’s hard to see what drew him to the atypical Project X, a science fiction movie which already seemed dated in the year that saw the release of both 2001: A Space Odyssey and Planet of the Apes.

My main interest in the movie is that it was based on novels by British sci-fi author L.P. Davies, particularly Psychogeist, which had left an impression on me when I read it in my early teens. Combined with elements from another novel, however, Edmund Morris’s script bears almost no resemblance to Davies’s work. (A television writer for the most part, Morris’s most notable theatrical credit is Edward Dmytryk’s Walk on the Wild Side [1962].) Castle’s movie belongs to a particular strain of sci-fi from that period, a mix of genre elements which lean towards the paranoid thriller – Byron Haskin’s The Power (also 1968), Lamont Johnson’s The Groundstar Conspiracy (1972, loosely based on another of Davies’s novels). Unlike those two, however, it’s set in the future, in a world in which the West and the East are on the brink of a catastrophic war.

Returning from Sino-Asia, agent Hagen Arnold (Christopher George) may possess vital information, but his memory has been wiped clean. A team of scientists led by Dr. Crowther (Henry Jones) is tasked with trying to unearth what he knows. Their plan is to create an entirely new personality for Arnold and put him into a scenario set a century or so earlier (the 1960s). How this is supposed to trigger the buried memories is none too clear; hiding out as part of a gang of robbers on the run from the police, Arnold is subjected to nightly experiments which use laser technology to visualize what’s going on inside his sleeping brain. These visions, a mix of psychedelic light show and rather crude Hanna-Barbera animation, gradually reveal what Arnold learned in enemy territory … and finally that he himself is the enemy’s secret biological weapon.

Rather silly, and very talky, Project X is an odd footnote in Castle’s career, mildly entertaining, with a decent cast doing their best to take the nonsense seriously; unfortunately for them, the script (unlike Crack in the World) fails to make the sci-fi concept convincing. Its chief interest lies in seeing Castle trying to branch out in a new direction, though he obviously falls short (as he did a few years later with Shanks). The disk includes a commentary and a half-hour featurette with Allan Bryce, David Flint and Vic Pratt talking about Castle’s gimmicks.

*

88 Films

Shortly before my heart attack I ordered a stack of disks from another British company, 88 Films, which I’ve only started to dip into.

There’s a four-disk set of Roger Donaldson’s Species (1995) and its three sequels. The original movie isn’t very good – an Earth-bound derivative retread of elements from the Alien franchise – and the sequels are an exemplary case of diminishing returns. It’s disappointing to see talented filmmakers going through the commercial motions – Donaldson and Species II (1998) director Peter Medak both have excellent work in their filmographies, but show little personality in these jobs-for-hire – but the two direct-to-video follow-ups don’t raise any expectations at all, although writer Ben Ripley somehow followed them up with Duncan Jones’s excellent Source Code (2011), a quantum leap ahead in its treatment of genre elements. Each movie gets a commentary or two, plus interview and behind-the-scenes featurettes.

Made on a far lower budget, so paradoxically more satisfying, is Danny Bilson’s Zone Troopers (1985). Produced by Charles Band’s Empire Pictures, it is the definition of “cheap and cheerful”, but skilfully executed on minimal means. A small unit of GIs caught behind German lines in World War Two try to fight their way back to their own army, but unexpectedly run into aliens who are trying to repair their damaged ship. The Yanks and aliens join forces against a superior German force in order to help each other make it home. There’s an inherent appeal for me in the mixing of genres and Bilson does a decent job with the war movie cliches before introducing the sci-fi element, so the story stays fairly well grounded. The transfer is pretty good for a cheap Empire production, and the disk includes a commentary and multiple featurettes.

I had fairly high expectations for Blood & Diamonds (1977), a poliziottescho from one of the masters of the genre, Fernando Di Leo. Everything seems to be in place – a thief gets out of prison, looking to straighten out his life; some thugs murder his girlfriend and he believes a crime boss is out to get him because the jewels from his last robbery are still unaccounted for; a somewhat sympathetic cop offers advice, but the girlfriend’s son is hostile; and everything hinges on the thief having misinterpreted a number of things which cause him to make bad decisions … it should all work, but for some reason the usually reliable Claudio Cassinelli, a veteran of the genre who more often played cops, turns in such a flat, uncommitted performance that he virtually sinks the movie single-handedly. The disk features a 4K restoration, with a commentary, a feature-length review of Di Leo’s career and a tribute to the director by actor Luc Merenda, who appeared in a number of Di Leo’s other movies, but not this one.

Still waiting in the pile are a few favourites which I’ve upgraded – Mario Bava’s Hatchet for the Honeymoon, Pupi Avati’s Zeder, Geoffrey Wright’s Romper Stomper, Herbert Ross’s The Seven-Per-Cent Solution, Lam Ngai-Choi’s Riki-Oh: Story of Ricky – plus some new titles – Lam’s The Seventh Curse, Chung Sun’s Human Lanterns, Sergio Sollima’s Violent City, Antonio Bido’s Watch Me When I Kill, Lucio Fulci’s Beatrice Cenci, and Alfred Chung’s On the Run.

*

Arrow

Arrow’s second volume of Shaw Brothers movies has just arrived, reminding me that I long ago got distracted and didn’t finish watching the first set – I should get on that right away!

I did recently watch two volumes of their Giallo Essentials, which are each three-disk sets gathering together previous releases. I actually had copies of two of the titles in the yellow set – Arrow’s own edition of Andrea Bianchi’s Strip Nude for Your Killer and the Blue Underground edition of Sergio Martino’s Torso. The Bianchi disk is identical to the previous stand-alone edition, but the Martino is an upgrade in quality of transfer, stacked with almost three-and-a-half hours of new extras plus a Kat Ellinger commentary. The main reason I ordered the set, though, was the inclusion of Massimo Dallamano’s What Have They Done to Your Daughters? (1974), which I hadn’t previously seen. More poliziottescho than giallo, it begins with the apparent suicide of a teenage girl which begins to look like murder. Inspector Silvestri (Claudio Cassinelli again, but much better here) investigates, eventually uncovering a ring of rich and influential men who indulge in sex with underage girls. But the closer he gets, the more witnesses are killed by a giallo-like killer in biker leathers and helmet, and eventually Silvestri’s superiors close the case before the wealthy degenerates can be exposed. One of Dallamano’s strongest movies, Daughters belongs to that particular strain of Italian exploitation which uses genre elements to comment on the contemporary political situation.

The black set contains three movies I hadn’t seen before. Silvio Amadio’s Smile Before Death (1972) is more like a ’60s psychological thriller than a giallo, a twisted family drama loaded with sex and violence, in which Nancy (Jenny Tamburi) returns home after the violent death of her mother (dismissed as suicide by the police) to find her photographer stepfather Marco (Silvano Tranquilli) shacked up with his mistress Gianna (Rosalba Neri). Since Nancy is due to inherit her mother’s estate when she turns twenty, she’s obviously in danger, but nonetheless becomes sexually involved with both Marco (who takes provocative photos of her) and Gianna. Kinky and visually stylish.

The Weapon, the Hour, the Motive (1972), like Lucio Fulci’s Don’t Torture a Duckling (also 1972), has a rural setting which is under the oppressive control of the Church. When a young priest is stabbed to death in church, the investigation uncovers layers of corruption – which also add a hefty dose of nunsploitation to the plot. With its unwholesome atmosphere and rural locations, the film is a strong addition to this exploitation side road, well-directed by Francesco Mazzei, who surprisingly has no other directing credits.

Giuseppe Bennati’s The Killer Reserved Nine Seats (1974) uses that favourite setting for horrific murders, an old theatre, and makes the most of its locations, including an abandoned castle, to cook up a menacing atmosphere. The castle’s owner Patrick Devenant (Chris Avram) invites a group of friends to the old family property which reputedly has a curse that results in a series of murders every hundred years. It doesn’t take long for a masked killer to start knocking people off – beginning audaciously with the actual stabbing death of Juliet during a performance of the climactic scene of Shakespeare’s play. Various tensions, betrayals and secrets bubble to the surface during a night which leaves quite a few corpses littering the premises.

All movies in these sets come with commentary tracks and interview featurettes.

*

And for something completely different, I also picked up Arrow’s limited edition of Mike Hodges’ Flash Gordon (1980), a movie I remain ambivalent about even after the passage of four decades. Hodges’ work has been uneven since his explosive debut with Get Carter (1971) and Flash Gordon may well be the least personal of all his features – there seems far more of producer Dino De Laurentiis than of Hodges in its camp cartoonishness. It appears to aim for the same target as Roger Vadim’s Barbarella (1968), but times had definitely changed. Not only does it seem out of date in the era of Star Wars and Alien; it also avoids the knowing perversity of Vadim’s movie – it’s hard to see who the target audience might have been. Still, while Lorenzo Semple Jr.’s script is embarrassing in its condescension to a supposedly naive audience, the garish colours and set design do have a certain charm. Perhaps the strangest thing about Flash Gordon is that it was originally to be directed by Nicolas Roeg, who had a much darker conception of the material; Hodges eventually took over to give Dino the live-action cartoon he wanted.

The two-disk set features an eye-popping 4K restoration, multiple commentary tracks, and hours of new and archival extras, including a feature-length documentary about star Sam Jones, plus a thick booklet, poster, and lobby card reproductions.

Comments

I actually just watched “What have they done to your daughters” for the 3rd(?) time. It’s got the feel of giallo in a poliziotteschi setting – Definitely an excellent blend! It’s also worth noting Cipriani’s powerful contribution.

For most gialli and poliziotteschi, the quality of the music usually goes without saying … someone should write a thesis about the excellence of Italian genre movie music. It’s unlike almost any other country’s and is a big contributor to what makes Italian movies so entertaining. In fact, in some cases it was the music that got me into the movies in the first place – particularly Morricone’s scores for Leone’s spaghetti westerns; I had the albums before I saw any of the films.