Revisiting some old favourites

Getting closer to the end of the year and the upcoming end of my 2022 Vinegar Syndrome subscription, maybe it’s time to re-evaluate my viewing habits. The monthly package from VS and fairly regular bundles from Severin have sucked me down quite a few rabbit holes which objectively are probably a waste of limited time. Did I really need to watch Stuart Rosenberg’s lame The Amityville Horror (1979) again, even though I know how absurd it is? But here’s the VS 4K restoration delivered automatically to my mailbox, so of course I do watch it again and it’s the same silly dud it always was. And there’s Tim Kincaid’s Mutant Hunt (1987), similar to his Robot Holocaust (also 1987), with a certain low budget charm, but by no means a good movie and certainly not a necessary investment of my time.

The list goes on – Worth Keeter’s silly James Bond pastiche Unmasking the Idol (1986), which admittedly had better-than-expected production values, but was most notable for the fact that the hero carried his tame baboon into every situation; undeniably better (or is that just a reflection of my long-standing taste for Asian martial arts?) are a pair of Yuen Biao thrillers, Corey Yuen’s Righting Wrongs (1986) and Clarence Fok’s The Iceman Cometh (1989), both in deluxe sets with multiple versions and loads of extras, and packed with spectacular action sequences and hair-raising stunts; my low-brow genre tastes were briefly satisfied with a new edition of William Sachs’ cheesy The Incredible Melting Man (1977), J. Christian Ingvordsen’s ambitious but under-funded Cyber Vengeance (1995) and Michael Findlay’s Shriek of the Mutilated (1974), another Sasquatch horror similar to but somewhat better-made than James C. Wasson’s Night of the Demon (1980), though fans are divided by the final revelation.

I may get around sometime to saying something about a few of these; or about Michael Pollklesener’s aggressively punk do-it-yourself Fuck the Devil (1990) and Fuck the Devil 2: Return of the Fucker (1991); or Mario Andreacchio’s Fair Game (1986), an Outback action movie in which a lone woman takes on a gang of vicious kangaroo-hunters (what raises the value of the Darkstar Blu-ray is the inclusion of a 90-minute collection of Andreacchio’s public service documentaries which inject drama and action into their messages). And what about Severin’s box set of sleazy Roman epics inspired by Tinto Brass’s Caligula (1979), Bruno Mattei’s Caligula & Messalina (1981) and Joe D’Amato’s Caligula: The Untold Story (1982), neither of which, ironically, can match Brass’s movie for exploitation excess?

Also from Severin: Jess Franco’s Faceless (1988), a belated homage to Georges Franju’s Eyes Without a Face (1960), which for a relatively late Franco movie adheres to generally held standards of conventional narrative filmmaking, with some unsettling gore, and one of his best casts ever in Helmut Berger, Stephane Audran, Telly Savalas, Anton Diffring, Howard Vernon, Caroline Munro, Chris Mitchum and Brigitte Lahaie – this is one Franco’s best meldings of his transgressive style with mainstream elements. Prolific genre writer Ernesto Gastaldi’s directorial debut, the psychological thriller Libido (1965), co-directed with Vittorio Salerno, gets a nice upgrade, while Joshua Grannell’s All About Evil (2010), draws on a number of influences, including the giallo, with uneven results in the story of a socially-inept woman who inherits a movie theatre and inadvertently finds success making and showing a series of videos in which she murders annoying people – Natasha Lyonne gives a very good lead performance and the murder set-pieces are well-staged, but the central conceit wears a bit thin.

I have dipped into my stack of Eureka Sammo Hung releases – Huang Feng’s The Shaolin Plot (1977) and Lau Kar-Wing’s Odd Couple – and Arrow’s special edition of Chema Garcia Ibarra’s The Sacred Spirit (2021), which includes a second disk of short films, requires some consideration, though I think I need to watch it again before venturing an opinion. I also spent a few days re-watching Patrick McGoohan’s The Prisoner (1967), which looks terrific on Network’s 2019 Blu-ray set, though the set itself is a little disappointing as if doesn’t include significant material from the earlier DVD release, most importantly the variant edits of the episodes “Arrival” and “The Chimes of Big Ben” and the feature-length documentary Don’t Knock Yourself Out (2007); in their place are Chris Rodley’s documentary In My Mind (2017) and a couple of episodes of McGoohan’s Danger Man series (1960-67), which is inevitably seen as the precursor to The Prisoner.

While the backlog of Vinegar Syndrome, Severin, Arrow, Eureka, Kino Lorber and Criterion disks continues to grow (I probably need some therapy sessions to get this under control!), lately I seem to spend more time revisiting older movies I haven’t seen in a while. Whether the urge is mere nostalgia, a search for a bit of psychological comfort, or a kind of laziness which avoids the demands of thinking about something new and unfamiliar is more than I can say. But even these movies are a mixed bag, and certainly not all confirmed cinematic masterpieces.

*

Tombs of the Blind Dead (Amando de Ossorio, 1971)

Amando de Ossorio’s Tombs of the Blind Dead (1971) was one of the first European movies influenced by George A. Romero’s Night of the Living Dead (1968), if not the best – that would be Jorge Grau’s Living Dead at Manchester Morgue (1974) – but it conjured up some haunting imagery and rooted its zombies in a culturally specific context. Rather than recently reanimated corpses, de Ossorio’s living dead are cursed Medieval knights who went over to the dark side during the Crusades and returned to Spain where they practiced black magic and human sacrifice before being blinded and executed by Church authorities. Now they haunt a derelict Medieval town, slaughtering anyone who ventures near, particularly at night. The victims are rather disposable, but the images of the blind, skeletal knights riding their dusty horses or closing in on foot listening for the heartbeats of their prey, have a nice poetic quality, and in the end they remain unvanquished, the final image as bleak as Romero’s downbeat conclusion. Synapse’s three-disk steelbook edition provides a nice 2K restoration from the original negative of the uncut Spanish original, plus a second disk with the shorter U.S. cut and a CD which isn’t the actual score, but a collection of tracks “inspired by” the movie, mostly leaning towards heavy metal. There are numerous supplements, including three commentaries, featurettes and a feature-length documentary focusing on Spanish zombie films.

Madigan (Don Siegel, 1968)

Double-dipping with Indicator’s release of Don Siegel’s Madigan (1968) wasn’t really necessary. The visual presentation is pretty much the same as Kino Lorber’s; there’s a different commentary track plus a brief interview with Richard Widmark and a 17-minute super-8 home viewing version, plus Indicator’s usual fat booklet, but watching it again less than three years after the Kino disk didn’t affect my impression of the movie in any way – it’s an interesting transitional work between classic police noir and the violent nihilism which overtook the genre in the ’70s after Siegel made Dirty Harry (1971).

Ocean’s 11 (Lewis Milestone, 1960)

Lewis Milestone was nearing the end of his long career when he made Ocean’s 11 (1960) – apart from a bit of TV work, all that was left was the troubled Mutiny on the Bounty (1962), which he took over after Carol Reed was fired – and the best that can be said of his work here is that it’s efficient. The first, and for what it’s worth best, of the Rat Pack movies in which Frank Sinatra and his buddies got together to have some fun, hopefully passing some of their self-satisfied amusement along to the audience, it’s mildly entertaining, with a leisurely pace, a few musical numbers thrown in (from Dean Martin and Sammy Davis Jr, but not from Sinatra himself – maybe his rates were too high for the budget?), and a nearly weightless plot which doesn’t take itself seriously enough to generate any real suspense. But while it seems pretty disposable, I always enjoy a heist movie and it’s still more enjoyable than the Soderbergh/Clooney series based on it. (Though if you really want to see a Vegas casino getting knocked over, Phil Karlson’s 5 Against the House [1955] is the better bet.)

A group of bored World War Two vets get together to commit an ambitious heist in Las Vegas, knocking over five casinos simultaneously on New Year’s Eve. The first hour is taken up with Danny Ocean (Frank Sinatra) and Jimmy Foster (Peter Lawford) gathering together their old buddies from the Airborne and pitching them the caper – we’re a long way in before the actual nature of the scheme is revealed. We get a little back story and various complications – electronics expert Anthony Bergdorf (Richard Conte) has just got out of prison and is separated from his wife and son; Jimmy’s mother (Ilka Chase) is planning to marry slick and shady Duke Santos (Cesar Romero); Danny himself has problems with estranged wife Beatrice (Angie Dickinson) and recent girlfriend Adele (Patrice Wymore) – but the elaborate heist itself is handled in a perfunctory way which doesn’t put much effort into the details or obvious complications. It must have taken the stars’ influence with all the real casino bosses to persuade those in charge of Vegas to let them make a big robbery look this easy. (The Warner Brothers Blu-ray includes a commentary and clips from the Johnny Carson Show.)

Nineteen Eighty-Four (Rudolph Cartier, 1954)

I first saw the 1954 BBC production of Nineteen Eighty-Four eleven years ago on a gray market DVDr. Some time later the BFI announced an official release, but that was then cancelled due to some rights issues. I was surprised to see it announced again, on Blu-ray no less, this summer and naturally ordered a copy, though there would no doubt still be quality issues – the original live broadcast was preserved as a kinescope, shot off a monitor which at that time would have been quite low resolution, so even filmed in 35mm, there wouldn’t have been a great deal of detail. All of which makes the quality of the BFI Blu-ray a pleasant surprise. What makes this particular upgrade so satisfying is that it was not only sourced from the 35mm kinescope negative; the production had used quite a lot of pre-filmed inserts, including exteriors of a London still marked by WW2 bombing, and these still exist as 35mm negative, so much of the new edition has a sharp film quality (like the BBC Blu-ray of Quatermass and the Pit [1959]). It’s a huge improvement over the DVD.

Written by Nigel Kneale and directed by Rudolph Cartier, who the previous year had made the first landmark Quatermass serial, the BBC production remains the finest adaptation of George Orwell’s bleak novel, deeply informed by the experience of totalitarianism from the ’30s and continuing into the ’50s. Made so soon after the War and just six years after publication of the novel, despite the technical limitations of television at the time, this version still has a sense of immediacy and danger absent from Michael Anderson’s 1956 feature or Michael Radford’s 1984 version which, while treating the material seriously, couldn’t escape the impression of being a reverent adaptation of an acknowledged classic. The book hadn’t yet attained that status in 1954, but was rather still an urgent warning about contemporary and potential political conditions in the post-war world. Kneale and Cartier captured that sense or urgency, with the help of an excellent cast led by Peter Cushing as Winston Smith, Andre Morell as O’Brien, Yvonne Mitchell as Julia and Donald Pleasence as Smith’s co-worker Syme.

The BFI’s dual-format edition includes a commentary by Jon Dear, Toby Hadoke and Andy Murray, a 1963 discussion by members of the cast and crew, a 2022 conversation between the BFI’s Dick Fiddy and television historian Oliver Wake, and a feature-length piece in which Hadoke and Murray look at the career of Nigel Kneale (in which it’s mentioned that the originally announced release some years ago had been abruptly cancelled due to the high fee demanded by the Orwell estate).

Phase IV (Saul Bass, 1974)

Saul Bass is best known as the man who revolutionized movie titles with dynamic graphic design and animation, setting the tone of the feature to follow rather than simply providing basic information about the cast and crew. He worked on movies for Otto Preminger, Robert Aldrich and, perhaps most notably, Alfred Hitchcock, for whom he designed the titles for Vertigo, North by Northwest and Psycho. By the time he worked on John Frankenheimer’s Seconds and Grand Prix, he was virtually creating miniature short films which served as prologues for their respective features. He brought his distinctive visual style to a number of educational shorts in the ’60s and ’70s and made a half-hour fantasy from a Ray Bradbury script in 1984, but he only directed one feature, Phase IV (1974).

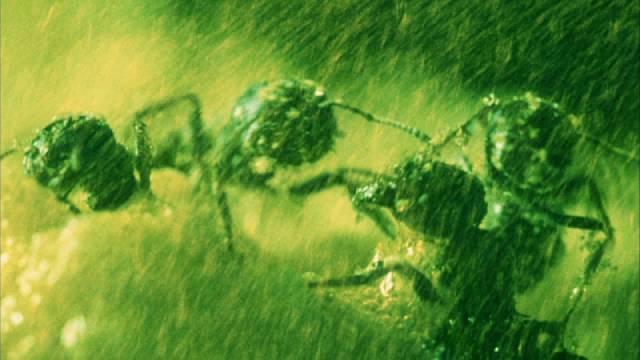

With a spare script by mostly-television writer Mayo Simon (who squeezed this in between John Sturges’ Marooned [1969] and Richard T. Heffron’s Futureworld [1976]), Bass not surprisingly focused on visual storytelling, with the obvious aim of following Stanley Kubrick’s lead into abstract science fiction. If Phase IV lacks the huge scope and grandeur of 2001: A Space Odyssey, it nonetheless conjures up a unique mood and some stunning imagery as it pits three characters stuck in a desert research station against huge ant colonies which appear to have gained a form of sentience and an ambition to replace homo sapiens as the planet’s dominant species.

After an opening which suggests that some cosmic force is influencing the ants, communications specialist James Lesko (Michael Murphy) arrives at the research station run by Dr. Ernest Hubbs (Nigel Davenport, no stranger to ecological catastrophe, having starred in Cornel Wilde’s No Blade of Grass in 1970). Hubbs needs Lesko to decipher signals somehow connected with the rapidly changing behaviour of the ants. Soon, local farmers come under attack and the research station is surrounded by a ring of strange structures, obelisks with highly polished surfaces, apparently constructed by the ants and now reflecting the sun’s rays onto the lab’s dome. Temperatures rise and ants infiltrate the equipment, sabotaging the generator and communications system. Hubbs refuses to call in help because he’s become obsessed with the ants and wants to complete his study.

A survivor from a nearby farm, the traumatized Kendra (Lynne Frederick, who had played Davenport’s traumatized daughter in No Blade of Grass), makes it to the station and ends up disrupting Hubbs’s experiments. As the situation deteriorates, the narrative becomes increasingly abstract, ending with a suggestion that the ants are grooming Lesko and Kendra to become a new Adam and Eve in a world they now control. Famously, the producers stripped away Bass’s intended ending, which would have more explicitly emulated the final section of 2001; as is usual in such cases, rumour inspired an idea that Phase IV had been left crippled, its profound themes undermined by crass commercial decision-making.

However, Bass’s ending eventually resurfaced and became easily viewable on YouTube some years ago. While interesting as a graphic designer’s montage, with the human characters lost in a landscape of geometric blocks overseen by giant ants, it’s so different from the essentially realistic style of the rest of the film that it’s perfectly understandable why the producers overruled Bass. For most audiences, it would simply have been baffling. The ending of the film as we now have it is vague, suggestive and open to interpretation, but it remains in keeping with the rest of the film, while Bass’s ending represents a radical break, an imposition of “deep meaning” which would seem rather pretentious in what is essentially a smart, unsettling creature feature.

While the character conflicts are fairly standard, the performances of Davenport, Murphy and Frederick are good, and the design has some very effective elements – the contrast between the lab with its electrical equipment and the sinister ant towers gives visual weight to the two very different intelligences in play – but what really lifts the film out of a predictable genre pigeonhole is the remarkable work of Ken Middleham, a specialist in macro photography (a couple of years earlier, he had provided the insect imagery for Walon Green’s “documentary” The Hellstrom Chronicle [1971], which shared Phase IV’s theme of humans’ inevitable replacement by insects); the closeups of ants are quite stunning, managing to convey an impression of intelligence and intent, particularly in the sequence in which the ants quickly acquire immunity to a deadly pesticide – one ant carries a pellet into the hive until it succumbs to the poison, then another takes over until it too dies, with the pellet finally delivered to the queen, which eats it. The camera tracks along the queen’s body until we see the steady delivery of eggs, which quickly change from the normal white to the green of the poison, indicating that the queen has begun producing a new mutant form resistant to the insecticide. Considering that Middleham was working with real ants, that this is not done with miniatures or animation, but with actual insects long before the dawn of CGI, it’s one of the most striking sequences in science fiction cinema.

The 101 Films Blu-ray looks stunning and, unlike the bare-bones Olive Films release from 2015, has substantial extras – a commentary track with film historians Allan Bryce and Richard Hollis, a 20-minute discussion by Jasper Sharp and Sean Hogan of the film’s meaning and place in the genre, plus Bass’s ending (with optional commentary). There’s also a second disk with more than two hours of Bass’s documentary shorts, the Ray Bradbury-scripted Quest (1984), and a lengthy talk by Bass about his work designing title sequences for other filmmakers.

Comments