Resurrecting a pre-tax shelter classic: The Rainbow Boys (1973)

I’ve seen so many movies over the past six decades that it must mean something when one has stuck in my memory for fifty years, even more so when that memory turns out to be fairly accurate. Not surprising, perhaps, for something as spectacular as Cy Endfield’s Zulu or Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey … but then there have been ample opportunities to see them again numerous times during the intervening years. But what about a small movie, seen just once in 1973, that has been lodged in some corner of my brain ready to resurface with a slight prompt?

For Gerald Potterton’s The Rainbow Boys (1973), that prompt came back during the summer when a restored copy was screened at the Cinematheque here in Winnipeg. I didn’t actually make it to the screening, but seeing it appear in the schedule triggered a pretty clear memory. One of the first Canadian features I’d ever seen, a small, character-based movie, it charmed me back then – and now that memory has been confirmed by watching the film for just the second time, thanks to a new Blu-ray from Canadian International Pictures. Made a few years before the infamous tax shelter years triggered an explosion of production, the movie is notable for its emphasis on character and landscape rather than the obvious genre tropes which would soon be exploited so vigorously by an industry often more concerned with cracking the American market than expressing anything distinctly Canadian.

It is indeed a slight film, a kind of road movie whose minimal “plot” serves as an excuse for three actors to enjoy themselves in some spectacular British Columbia landscapes. It obviously had taken up residence in my head because of the cast – Donald Pleasence, Don Calfa and Kate Reid – all of whom edge up to the precipice of over-acting, but just manage to keep from plunging over. The comedy is quite broad, but Potterton and the actors maintain a delicate balance, with charm never slipping into caricature.

Pleasence is Ralph Logan, a transplant from England who pans for gold in a mountain river, trading specks of gold dust for cans of beans at a general store in the small town where his disillusioned friend Gladys (Reid) lives. Logan is paranoid about people stealing his finds, small as they are, glancing around suspiciously and muttering “bastards!” to himself as he finds a tiny speck of ore among the pebbles in his pan on the riverbank. When New Yorker Mazella (Calfa, early in his long and eclectic career) rolls into town on his seemingly home-made three-wheeler motorcycle, he serves as a catalyst; he’s ridden west because he came across a book about lost mines in the mountains and decided to go treasure hunting. It turns out that Logan’s father (who had abandoned his family back in England) had a claim and supposedly dug out three-hundred pounds of gold before he died. It’s still up there somewhere and Logan has a map … but he’s never gone to find the mine because as long as it exists only as a possibility, the dream sustains him.

Now, at Mazella’s prompting, Logan digs out the map and, with Gladys along for the ride, the trio head off on the bike looking for Logan’s father’s mountain. And that’s it for plot. They bicker and argue and encounter some First Nations people along the way who see the Europeans as objects of amusement. Logan delivers long, rambling monologues about his dad, about the war, about life. In a way, the movie seems to exist just to provide Pleasence with an opportunity to flex his character muscles, which he does beautifully, drawing on his experience with the work of Harold Pinter, in which seeming nonsequiturs and trivialities become the essence of the drama (or comedy). This is one of Pleasence’s most enjoyable performances, ably and generously supported by Calfa and Reid, who obviously recognized that this was his movie and they were there for him to bounce his character off. Which is not to belittle their own work as it adds decorative touches around Pleasence’s gem.

Almost as important as the performances, and providing a setting which enriches the actors’ work, is Robert Saad’s cinematography. Despite there being only three characters, the film feels expansive with its wide views of the mountains and valleys around Lytton, British Columbia, which is located at the confluence of the Fraser and Thompson Rivers. (Although the movie feels very Canadian, the setting is never named beyond being “the Pacific northwest”, permitting a potential audience to assume that it’s located in the States – itself typical of Canadian movies back in the ’70s and ’80s.) If I have one quibble, it would be Howard Blake’s score, which leans a bit too hard on silent comedy motifs which unnecessarily provide an exaggerated emphasis on what ought to be subtler comic effects.

Writer-director Potterton, himself a transplant from England, obviously had a taste for that kind of comedy. He worked at the National Film Board in the ’60s as an animator and short film maker and, apart from the Academy Award-nominated My Financial Career (1962), an animated adaptation of a Stephen Leacock story, his most significant film was essentially a two-reel silent comedy starring none other than Buster Keaton. The Railrodder (1965), one of no less than seven movies Keaton appeared in the year before his death (and released just a few months before the very different Film by Alan Schneider and Samuel Beckett), is a travelogue packed with physical gags which at times appear unsettlingly dangerous for the 70-year-old comedy master.

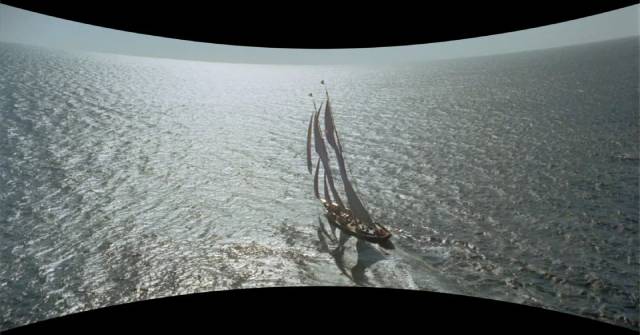

Buster is first seen reading a paper in London; he sees an ad urging people to visit Canada and immediately jumps off a bridge into the Thames, emerging in the next shot from the Atlantic on the east coast of Canada. Walking up from the beach, he finds a motorized maintenance cart on a railway track, hops aboard and begins a trip from coast to coast. As the landscape changes around him, Buster makes himself at home on the little vehicle, preparing meals, doing laundry, shooting geese … and standing on the little platform, taking pratfalls, getting wrapped in a gigantic map, continuously at risk of losing his balance and falling off as he speeds down the track. Forty years after The General (1926), he’s as deadpan and fearless as ever, but for a viewer the comic touches are now tinged with much more concern for his safety than when he was an agile younger man.

The Railrodder is included on another Canadian International Pictures release, along with John Spotton’s Buster Keaton Rides Again (1965), a documentary about the making of the short. This record of Buster at work, taking things very seriously while making his performance look almost careless and effortless, is fascinating. He’s obviously as much co-director as star and there are numerous moments when we see Potterton deferring to Keaton’s judgment, though they do butt heads at one point over a gag involving a trestle bridge and several other maintenance carts on the same track. Buster has very definite ideas, but initially the plan is changed at the last minute and he seems really irritated because Potterton and the crew don’t understand the precision with which he creates a gag. In the end, they re-do it his way.

The Railrodder was one of several live-action shorts Potterton made at the NFB, but The Rainbow Boys was his only live-action feature. He returned to animation and, with The Rainbow Boys quietly disappearing after limited distribution, became best-known for overseeing the direction of Heavy Metal (1981) for producer Ivan Reitman.

*

I have a couple of tangential connections with the Blu-ray of The Rainbow Boys as it was produced by Zellco Entertainment, a local Winnipeg company run by producer David Zellis, whom I’ve known for years, and the 4K scan was made by my employer, Library and Archives Canada, from an interpositive held in their collection.

The disk includes a commentary with Potterton, producer Anthony Robinow and composer Howard Blake, as well as an interview with Potterton which runs almost an hour. Writer, filmmaker and friend of Don Calfa Gary Smart provides a half-hour appreciation of the actor. There are also four animated shorts directed by Potterton from scripts by Pinter, and two brief featurettes about the restoration.

The Buster Keaton Rides Again disk includes six animated and live action shorts by Potterton in addition to The Railrodder, with a commentary by Potterton and David De Volpi on the documentary. In addition, there’s a fifty-minute Cinerama-style travelogue by Eugene Boyko called Helicopter Canada (1966), produced by the NFB to mark the country’s centennial; seen now, the things it celebrates seem quite horrifying, with spectacular imagery of human activity and industry ripping the land apart for exploitable resources – land stripped bare by mining companies, a river whose surface for miles is concealed by thousands of trees floating down to pulp mills … all this is lauded by narration which sees nothing but “progress” in environmental destruction.

Comments