2022 reading

I notice that I didn’t mention any of my reading last year. In part this is because much of that reading doesn’t really connect with the focus of the blog (though I’ve probably mentioned in passing that I’m still occasionally reading Simenon’s Maigret novels). However, the year was framed by two books that obviously do have some bearing on what I write here.

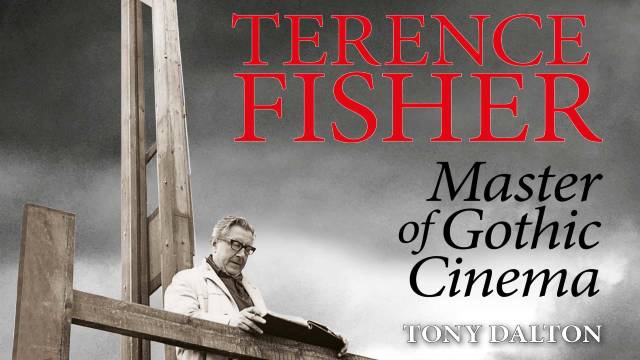

Tony Dalton’s hefty biography of Terence Fisher from FAB Press bridged the turn of the year. Terence Fisher: Master of Gothic Cinema, an oversized softcover with five-hundred copiously illustrated, double-column pages, definitely qualifies as exhaustive. While the portrait of Fisher it paints is clearly influenced by Dalton’s long friendship with the filmmaker – the author is unfailingly positive about Fisher’s qualities as a person – it does try to maintain an objective view of the movies themselves, recognizing their importance in British film history and their influence on the horror genre, which was felt in both Europe and the U.S., while nonetheless acknowledging their flaws.

Not surprisingly, the most enlightening sections of the book cover Fisher’s early life and the stages of his entry into a career in movies, with the later sections given over more to an account of the films themselves and Fisher’s struggles to sustain that career in an industry undergoing rapid changes in the ’60s and ’70s during a time when he was growing older and dealing with health issues. But before all that, he had trained for a life at sea, beginning as a cadet and eventually getting a mate’s certificate and finding work on ships belonging to Canadian Pacific and later P & O. Despite doing well and receiving glowing recommendations from his employers, he eventually decided this wasn’t really what he wanted and he returned to London and got a job with a large department store, his favourite part of which was designing window displays.

He was already in his late twenties when he decided that a long-standing interest in movies might be worth pursuing and he entered the industry as “the oldest clapperboy in the business”, doing work usually performed by entry-level teens. After a year-long apprenticeship, he joined the editorial department at British Gaumont as an assistant, eventually working his way up to editor on quota quickies. He proved to be a valuable asset, working quickly and efficiently – his editing skills would prove very useful when he landed at Hammer Films in the ’50s, making movies on very small budgets – and after a decade of this work, and now in his mid-40s, he finally got an opportunity to direct, making half-a-dozen movies – comedy, romance, suspense – before really hitting his stride with the period mystery So Long at the Fair (1950) for Gainsborough (although Fisher got a co-director credit with Antony Darnborough, by all accounts he worked alone on the film).

Despite that film’s quality, Fisher didn’t remain at Gainsborough and landed at Hammer in 1952 … the rest, as they say, is history. Well, kind of. He spent five years making essentially B-movies for Hammer before decisively transforming the studio with his hugely successful Curse of Frankenstein (1957) and Dracula (1958). But the decisive impact of that pair can only be seen clearly in retrospect; between them, he made another B-movie and worked on no less than five television series. It was only after Dracula that he settled down to make mostly Gothic horror movies, with occasional diversions into historical adventure and science fiction.

It’s ironic that Fisher himself wasn’t particularly comfortable with horror, something which back in the day I seemed to sense – he was more interested in the romantic aspects of the stories he was assigned and it took me a long time to appreciate what he was doing (I tended to prefer the films of John Gilling, which seemed less stodgy, harsher in their treatment of the horror elements in stories not much different from those being handled by Fisher). The Gothic tradition is rich in romance as well as horror, and Fisher simply leaned more towards that pole (more Mrs. Radcliffe than Matthew Gregory Lewis). My opinion evolved over several decades as I watched and re-watched the Hammer movies, so reading Dalton’s book hasn’t had a noticeable impact, though learning more about Fisher’s personality has helped to confirm my view of the films. Strangely, I even found myself a bit less critical than Dalton of some films – he has a fairly low opinion, for instance, of Four Sided Triangle (1953), which I’ve always rather liked, an early attempt by Hammer at science fiction which, for me at least, benefits from Fisher’s greater interest in the romantic aspects of the story than the mechanics of the protagonist’s matter-duplicating device.

*

Reflecting back obliquely to Fisher’s Gothic movies, I spent much of December tackling Powers of Darkness, an alternative version of Bram Stoker’s Dracula, which proved to be very disorienting. It’s probably been three decades since I last read Dracula (for the third time), so my memory of details is no doubt a bit hazy, but the many divergences of this rediscovered version kept clashing with what I did recall.

Powers of Darkness has mysterious origins which are not cleared up by a lengthy introduction. It was originally published in Swedish a couple of years after Stoker’s novel appeared in 1997. Serialized in a newspaper, it’s almost twice as long as the official version, but it remains unknown whether it was based in part on earlier drafts (Stoker worked on the book for many years), or whether the unknown translator had merely used Dracula as a starting point and expanded and embellished it into this very different novel.

It’s more clumsily structured than Dracula – it doesn’t weave the various “documents” together into a tight, coherent narrative, but rather delivers the various characters’ journals in large, uninterrupted chunks, so the different narrative threads seem barely to connect. This suggests that it may actually be an early draft which Stoker later refined. But then the focus of the narrative is so different from the familiar story that it also suggests that another author is using some of the raw materials to explore their own interests. That focus is on political and social issues which are simply not present in Dracula.

In Powers of Darkness, vampirism remains pretty tangential; Draculitz (as he’s called here – many names are different from the official version) is heading for London to lead an international conspiracy to overthrow the established order of society and create a Fascist order in which the “superior” natural ruling class will dominate the degenerate underclass. Carfax, the estate he has purchased, is occupied by a multi-national elite of aristocrats, intellectuals, artists and occultists, who exert a supernatural influence over those who are drawn into their sphere.

The core group of characters who work against Dracula in Stoker’s novel never coalesce here – in fact, Dr. Seward, Arthur Holmwood and Quincy Morris all die on the periphery of the action, while Professor Van Helsing, Harker and Mina join forces with a pair of detectives who are tracking what they believe to be a purely political conspiracy, only in the final pages coming to acknowledge that Van Helsing’s crazy ideas about supernatural evil are the actual driving force of that conspiracy. But this group only come together decisively in the last eighty or so pages of the eight-hundred page book. There’s no breathless chase across Europe back to the Count’s castle for a final showdown – instead he’s disposed of a few pages from the end in one of his safe houses in London – while Lucy, who was his first victim in England and became a vampire about four-hundred pages in, instead of being the proof for everybody that supernatural forces are at work, is forgotten about until a brief epilogue in which she’s staked a couple of pages before the end of the book.

But there are major changes right from the start, with Dracula’s opening four chapters – Harker’s journal of his experiences at Castle Dracula – expanded to two-hundred pages. One of the original’s first and most potent shocks, the three vampire brides being diverted from an attack on Harker by Dracula tossing them a sack containing a wriggling baby, is missing. In fact, the three brides are replaced by a single female vampire who repeatedly tries to seduce Harker – and almost succeeds in undermining his British rectitude with her potent erotic wiles (throughout the book, there are explicitly erotic scenes much steamier than anything in the more reticent Dracula).

Not only this; Harker’s explorations reveal vast underground chambers populated by a degenerate subhuman race which apparently are the remnants of the Count’s family line. These ape-like creatures practice pagan rites over which Draculitz presides as high priest, in which virgins are ritually slaughtered and their blood drunk by the congregation. This nod to the idea of evolution from a lower to a higher form doesn’t really mesh well with the social Darwinism of the Count’s political conspiracy as it seems to root him firmly in a degenerate past rather than show him as representative of a superior race.

While literary detectives (including this edition’s translator Richard Berghorn) try to untangle the book’s history, it’s certainly not going to displace Stoker’s Dracula, which is a more well-formed novel. (Centipede Press rather misleadingly subtitles their edition as “The First Dracula” as if this question of origins is settled.) A rather exhausting reading experience, Powers of Darkness is a curious sidelight, hidden for a century and reappearing after yet another version of the story was discovered in Iceland and translated back into English in 2017. That, also called Powers of Darkness, turns out to be a severely abridged translation from this Swedish edition, rather than a direct translation from the English version. It’s all very complicated and confusing.

Although there’s a softcover edition of Breghorn’s translation readily available from Amazon and elsewhere on-line, being a sucker for something collectible I opted for the limited, numbered edition from Centipede Press (mine is #355 of 500), which is very nicely produced, with a spectacular dust jacket, and more than a dozen full-page illustrations by several different artists, plus Breghorn’s introduction, a foreword by Dacre Stoker (Bram’s great-grand-nephew) and notes on the translation by editors S.T. Joshi and Martin Andersson. Whatever its merits as a literary artefact, it’s certainly an impressive object and I don’t really regret the expense.

*

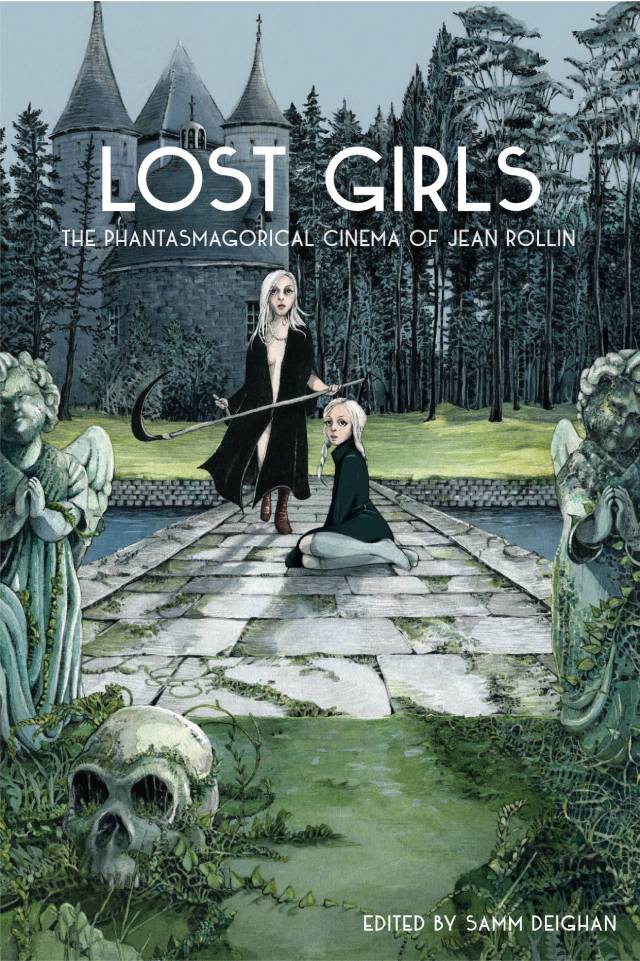

Between these two, my only other major film-related reading was Lost Girls: The Phantasmagorical Cinema of Jean Rollin, a collection of essays edited by Samm Deighan and first published in 2017 by Spectacular Optical. I was frustrated because I only came across references to the book after the limited edition had already sold out, but this year it was finally issued as an e-book, so I got to read it after all.

The first thing to note is that all the essays are by women writers, providing an interesting perspective on a filmmaker whose work was often dismissed as sexist and exploitative because, it’s true, much of it does linger on the naked female body. By situating Rollin’s work in artistic practices which are not specifically cinematic – art and literature which draws on 19th Century romanticism and early 20th Century surrealism – his treatment of sexuality comes to seem much more nuanced than it might at first seem.

Although the essays are rather uneven – some are steeped in academic jargon and belabour their points – the cumulative result is a sympathetic portrait of a serious artist who worked on the fringes of the French film industry, ignored for the most part, treated with disdain by many who bothered to notice him, but always exploring his own thematic interests and eventually creating a body of work which transcends its budgetary constraints and the distortions imposed by commercial demands. As a long-time fan of Rollin’s movies, it was gratifying to encounter so many writers who not only share my interest in his work but also support that interest with an impressive depth of scholarship.

Comments