Political thrillers, horror and metaphor

To make a very broad generalization, there are two types of political thriller: ones firmly grounded in real politics and ones which use politics as a narrative device. The former often have a documentary quality, like Gillo Pontecorvo’s Battle of Algiers (1966) and Costa-Gavras’ Z (1969). The latter often lean towards something akin to the horror film, driven by a generalized paranoia about unseen forces working behind society’s facade, like Alan J. Pakula’s The Parallax View (1974) and Sidney Pollack’s Three Days of the Condor (1975). Things can become a bit more complicated when genre tropes are applied to real events, transforming reality into metaphor, which can trivialize or at least distort real issues. What works just fine in fiction may become problematic the closer it gets to the real.

Three recent releases approach political issues in strikingly different ways, producing quite different results.

Les Chiens (Alain Jessua, 1978)

I first saw Alain Jessua’s Les Chiens (The Dogs, 1979) in Hong Kong in November 1980 and, according to my notes, didn’t think much of it. Seeing it now for the second time, forty-two years later, my judgment has changed – in fact, I can’t actually recall why I was initially disappointed though it’s probably because I was expecting something closer to a more conventional horror movie. Although it’s steeped in an atmosphere of menace, it uses tension and violence to evoke the threat of fascism in a class-bound society which resembles contemporary France, but also has a slightly futuristic air.

Set in a modernist suburb of concrete and glass, this community has a discomfiting lack of history and cohesion. The wealthy bourgeoisie live in fear of immigrants and unemployed youth; feeling threatened, they have come under the influence of Morel (Gérard Depardieu), a man who trains and sells guard dogs. Each dog is tailored to its owner, and it becomes clear that Morel is actually shaping human rather than animal behaviour, instilling a sense of distrust of others, while providing a shared psychological identity among his clients. Here, four decades ago, Jessua lays out the mechanisms which have taken over the modern Right in Western democracies; paranoia amplified by contrived social threats.

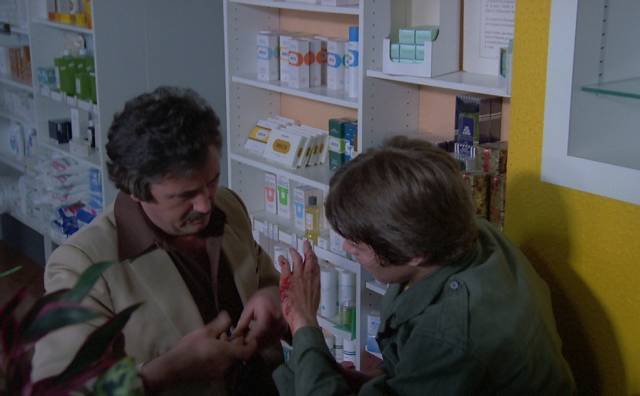

The protagonist is the newly arrived Dr. Henri Ferret (Victor Lanoux), who is concerned by the number of dog bite injuries he encounters. When Elisabeth (Nicole Calfan) is raped one night, he becomes involved with her and watches as she’s drawn into the dog owners group; seeking security after the attack, her personality gradually changes and Ferret is himself menaced by her dog. His encounters with rebellious delinquents and immigrant workers confirm that Morel’s influence, couched in benevolent rhetoric about helping to make people safe, is actually leading to the death of “undesirable” elements in the community. Rather than security, he is producing division and hatred along lines of class and race, with privilege justifying the destruction of those who make the wealthy uncomfortable.

I probably wasn’t attuned to the political subtext (actually not very “sub”) the first time I saw Les Chiens, but now it seems quite prescient. In order to gain and consolidate power the Right preys on tribal instincts, using alarmist provocations to stir up fear and hatred. This manipulation of the more primitive parts of the human brain bypasses reason; in a state of agitation, people can be led to act against their own, and their society’s, best interests. There are several sequences in the film which deal with owners training their dogs to attack, but it quickly becomes clear that it’s the owners themselves who are being trained, specifically to see other people as justifiable objects of attack – supposed social threats are no longer perceived to share a common humanity. The owners themselves are being moulded into animals driven by instinct.

Jessua was not a prolific filmmaker, but his thrillers use metaphor effectively to make their political points – here and in Shock Treatment and Armageddon.

(Severin Blu-ray, including interviews with composer René Koering and critic Emmanuel Le Gagne)

*

Mindfield (Jean-Claude Lord, 1989)

Jean-Claude Lord’s Mindfield (1989) bases its fiction on a troubling reality and in so doing trivializes the very real suffering of actual victims of medical experiments conducted by a doctor whose “research” was funded by intelligence agencies. Scripted by novelist William Deverell with filmmaker George Mihalka, who was originally slated to direct, the movie uses that reality as background for a conventional thriller about a Montreal cop with psychological issues who finds himself in the middle of a case in which a number of people are being murdered, only to be brought eventually face to face with his own suppressed past.

Ewan Cameron was an influential psychiatrist, born in Scotland and eventually splitting his time between the U.S. and Canada. At various times he was president of the Canadian, American and World Psychiatric Associations, and in 1945 served as a consultant at the Nuremberg trials. This last was ironic in light of his subsequent career, which was rooted in essentially eugenics ideas about rooting out from society inherently “weak” people, whose mental illness he felt contaminated the “healthy”. Largely funded by the CIA through their MKUltra program, he experimented on patients at the Allan Memorial Institute at McGill University in Montreal without informing them of exactly what he was doing; without informed consent and given the extremity of his methods he was disturbingly similar to the Nazi doctors who experimented on the inmates of concentration camps.

His theory was that conditions like schizophrenia were rooted in experiences and memories which could be erased and replaced with beneficial new memories. He used drugs like curare to put patients into prolonged comas during which they would be subjected to tapes implanting new ideas. He used extremely high electroshock doses and powerful psychotropics like LSD to wipe minds clean. All this was done to ordinary people who had come seeking help for things like post-natal depression and anxiety. His “psychic driving” ruined the lives of numerous people, many of whom never regained normal functions (some of them attempted to sue the CIA on the late ’70s and ’80s). Whether or not Cameron actually knew that his funding came from the CIA isn’t clear, but his methods eventually became the basis for the methods of torture used by the agency to extract information from “reluctant sources”.

This is a real-life horror story rooted in post-war paranoia, but the story told by Deverell, Mihalka and Lord reduces it to the generic terms of a 1970s paranoid thriller, made a decade or so too late. Yet, although Mindfield doesn’t have a good reputation (most reviews find it routine and dull), for what it is it’s efficiently made and passably entertaining.

Kellen O’Reilly (Michael Ironside) is a cop who’s losing his grip on reality. With the recent relatively amicable break-up of his marriage, he finds himself attracted to Sarah Paradis (Lise Langlois), a lawyer working simultaneously with the police union and a group of patients trying to sue the CIA for damage done to them by Dr. Satorius (Christopher Plummer), whose work was funded by MKUltra. By coincidence, O’Reilly and Sarah are present during what initially appears to be a botched robbery at a drug store. But something doesn’t feel right and O’Reilly believes it was just cover for a targeted hit. His suspicions irritate his superiors, who are aware that he’s seeing a psychiatrist and may not be in full control of himself – something seemingly confirmed by his violence in several encounters with what we know to be a hit squad sent to Montreal by unknown masters in the States.

Put on suspension, O’Reilly refuses to give up, becoming a target himself. It turns out that the killers have been sent to retrieve a crucial piece of evidence linking Satorius to a CIA program to transform patients into programmed assassins. The evidence is a reel of film showing a demonstration of the conditioning’s effectiveness – the subject being none other than O’Reilly himself, who had entered Satorius’ institute for depression due to his cop father’s suicide. As O’Reilly pursues the killers, the false implanted memories break down and he discovers his real past. The final big showdown comes as the police have a strike rally at the Olympic Stadium and the bad guys kidnap Sarah.

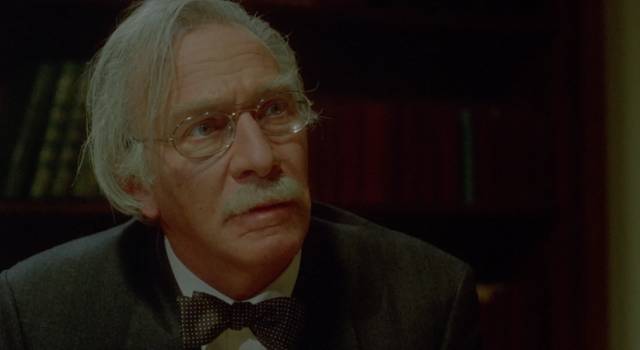

Essentially a B-movie plot, Mindfield’s story loses sight of the genuine horror of Cameron’s unethical human experiments, though it does reflect reality in the court’s dismissal of the lawsuit for lack of evidence linking the CIA to the doctor’s work. I’m not sure what significance there is in changing the real-life monster’s identity from Scottish to some kind of undefined eastern European, but Plummer is effective in what amounts to a minor supporting role as a misguided idealist. Ironside is passable as the troubled hero, though in a long career he has always seemed more comfortable as a villain (he was the psychotic killer in Lord’s tax shelter slasher Visiting Hours [1982] earlier in the decade).

As for Lord, he had a five-decade career during which he made kids’ movies, sci-fi action, straight dramas and sports movies, as well as episodic television, but apart from Mindfield I’ve only seen Visiting Hours, so I can’t vouch for his overall stature as a figure in Quebecois and Canadian cinema.

(Canadian International Pictures Blu-ray, with a commentary, and brief interviews with co-writer and original director George Mihalka, producer Tom Berry, and co-star Lisa Langlois)

*

La llorona (Jayro Bustamante, 2019)

Real-life horror also lies behind Jayro Bustamante’s La llorona (2019), a repurposing of the Latin American myth of the crying woman as a way to address the trauma of genocide perpetrated by a military dictatorship in Guatemala during the civil war which lasted from 1960 to 1996. Here, though, that metaphoric/mythical element provides a way into a reality difficult to grasp head-on, rather than using that reality as a jumping off point for entertainment.

Addressing something like genocide in a piece of fiction is tricky at any time; to do it through a small personal story risks trivializing the historical reality; adding an element of supernatural horror compounds the risk. That Bustamante largely succeeds is an impressive creative feat. His starting point is the 2013 trial of Efrain Rios Montt, a military officer who briefly became dictator in the early 1980s, whose “counter-insurgency” operations marked one of the bloodiest and most brutal stages of the civil war. Thirty years later, he was indicted for crimes against humanity. However, his conviction in May 2013 was overturned ten days later by a higher court which ruled that he had been denied an adequate defense. A retrial in 2015 was suspended when he was deemed too old and sick for the process to continue.

In the film, Montt becomes General Enrique Monteverde (Julio Diaz), an elderly man outraged that he’s been put on trial for acts he considers were essential to protect his country from the scourge of communism. Race and class are woven through the fabric of Guatemalan society; he represents the natural authority of a ruling class with its roots in European colonialism, while the “enemies of the state” are the indigenous people fighting for rights of self-determination. The General’s wife Carmen (Margarita Kenéfic) is a patrician figure who has no doubts about her husband’s rectitude and the necessity of anything he might have done, actions about which she would prefer to know nothing.

The humiliation of appearing in court is amplified by crowds of protesters who gather in the streets to shout accusations and insults at the General as he’s chauffeured back and forth to the trial. He seems to be retreating into himself, his mental state deteriorating, perhaps declining into dementia. At night he’s woken by sounds in the house and wanders from room to room with a gun in his hand, searching for intruders. When Carmen goes looking for him, he shoots, barely missing her. Between his potentially dangerous state of mind and the crowds outside, most of the servants abandon the family, leaving only Valeriana (Maria Telon), who has served faithfully since arriving as an adolescent – and may be an unacknowledged illegitimate daughter fathered by the General with an indigenous woman.

One day, a sombre, silent woman makes her way through the crowd and arrives at the door. It’s assumed that Alma (Maria Mercedes Coroy) has been sent from a remote village to serve as a replacement housemaid. With her arrival, the atmosphere in the house subtly changes. She befriends the General’s granddaughter Sara (Ayla-Elea Hurtado), but at times seems vaguely threatening – teaching the young girl how to hold her breath for a long time, she holds her under water, turning a game into something menacing. Water gradually assumes an importance whose significance isn’t initially clear – part of the house is flooded one night, the swimming pool becomes weed-choked, with Sara entangled under the surface. And in the streets outside, the crowd undergoes a transformation, the angry chants giving way to an ominous silence as a growing number of indigenous people hold up photographs of their murdered family members.

While the General and Carmen cling to their sense of privilege, their daughter Natalia (Sabrina De La Hoz) and Sara wake up to the reality of what the old man had done, the realization that their own social position rests on a horror which it’s no longer possible to sanitize with political slogans. Finally, even Carmen is forced to acknowledge the truth when she’s given a vision of her husband’s crimes, a vision in which she lives out Alma’s memory of being hunted down by the General’s men, forced to watch as her children are drowned in a river and at the moment of her deepest anguish casually shot by the General himself. Alma is none other that La llorona, the spirit of a grieving mother lamenting the murder of her children – but not seeking revenge so much as an acknowledgement of guilt from those responsible for her grief.

The film itself is an attempt to elicit such an acknowledgement of the historical crimes committed by a privileged ruling class which even years later asserts that those horrific actions were a necessity. The narrative is astute enough to know that it’s unlikely that the perpetrators will acknowledge their guilt, but holds out the possibility that subsequent generations have the capacity to understand. More specifically, it’s the women who are capable of sharing the victims’ grief and pain, of expressing empathy and a shared identity which may break down the barriers of class and race.

While La llorona offers this note of hope, reality remains dark. The right-wing government was not happy about the production, which was largely shot inside the residence of the French ambassador; demanding that shooting stop, the foreign ministry even threatened to expel the ambassador from the country. Like General Monteverde, the ruling class would still like to suppress the truth of historical crimes in order to justify their continued position of privilege.

Although he weaves elements of supernatural horror through this story rooted in historical horrors, Bustamante’s style is rather cool and formal. There are no jump scares, but rather a steadily accumulating sense of unease; he uses precise framing and subtle camera moves to suggest something slightly off-kilter. It’s only late in the film, specifically when Carmen is drawn into Alma’s memories, that Alma’s status as a supernatural figure becomes unequivocal … until then, it’s her identity as a Mayan woman, a figure subjugated by her employers, relegated to a lower status, which highlights the social inequalities manifest in the crimes for which the General is on trial. It’s this subtlety which makes the film’s metaphor work without distracting from or trivializing the historical reality.

The process of making the film reflects Bustamante’s thematic concerns. Working largely with non-professionals, he spent months developing the project with his cast, drawing on their own experiences to shape the narrative (Coroy drew on her own grandmother’s experiences during the genocidal assault on the Mayans by the Guatemalan military to embody Alma’s tragedy). The result is an unforced authenticity in the performances which helps to make the uncanny aspects of the narrative seem natural and convincing.

Shot digitally, the film has a cool, lucid look on Criterion’s Blu-ray. The supplements – an interview with the director (28:46), a making-of documentary (44:15), and a booklet essay by writer Francisco Goldman which covers both the making of the film and the history on which it’s based – provide an interesting look at Bustamante’s process and the historical background to the story.

Comments