Recent Arrow releases, part two

Nightmare at Noon (Nico Mastorakis, 1988)

It’s one of those odd mysteries that Arrow has developed such an attachment to the movies of Nico Mastorakis. The fairly prolific Greek exploitation filmmaker seldom displays much panache as he works his way through familiar (and sometimes not so familiar) genre tropes. Usually rather plodding, his movies do occasionally toss out oddly unexpected details – big-jawed, muscle-bound Brian Thompson going undercover as a gay fashion designer to bring down brutal dictator Oliver Reed in Hired to Kill (1990), for instance. I didn’t know anything about Mastorakis before I watched Arrow’s Blu-ray of his second feature, Island of Death (1976), but because that one appealed to me I’ve bought a number of other releases, each of which have elements I like, but none of which have seemed as engaging as that decidedly perverse introduction.

The latest release is Nightmare at Noon (1988), a riff on bio-hazard movies like George A. Romero’s The Crazies (1973), George C. Scott’s Rage (1972), Graham Baker’s Impulse (1984) and Hal Barwood’s Warning Sign (1985). The essence of these movies is the malevolence of powerful people who either accidentally or on purpose contaminate small communities with toxic chemicals or biological weapons, sitting back to observe the effects, and eventually destroying the community to cover up their acts.

In Nightmare at Noon, the villains appear to be foreign agents who contaminate the water supply of a small desert town (Moab, Utah, a favourite location for Hollywood westerns and stories set on alien planets), overseen by Brion James with bleached hair and effete mannerisms. Having poisoned the water, they seal off the town by cutting phone lines and placing magical EMP devices at all exit points so vehicles die when they try to leave. Trapped in town are all the locals plus high-powered entertainment lawyer Wings Hauser and his trophy wife (Kimberly Beck) and the hitchhiker they’d given a lift, Bo Hopkins, who turns out to be an ex-cop who’s wandering the country seeking atonement for killing someone who wasn’t armed.

In town, sheriff George Kennedy and his deputy daughter (Kimberly Ross) try to cope with the escalating violence as people go crazy, attack each other, and bleed green acid (the silliest unnecessary detail). There’s a lot of bickering – much of it courtesy of Hauser’s privileged whiner – fist fights and shoot outs and a gradually diminishing cast as characters die nasty deaths. Eventually, having figured out what’s going on, Bo, Wings and Ross head into the desert on horseback in pursuit of James, who is preparing to leave now that he has his data, killing all his own men as he goes. This gives Mastorakis an opportunity to try his hand with western tropes for a few minutes before winding up with a spectacular but totally extraneous helicopter chase through desert canyons. Although this has nothing to do with the rest of the story – well, tangentially, as the chase is between the chopper which arrives to pick James up, though he’s killed before he can get on board, and an air force helicopter sent to intercept it – it’s a visually spectacular bit of action with what looks like some genuinely dangerous manoeuvring.

I wouldn’t call Nightmare at Noon a good movie, but there’s a lot to enjoy in it, not least a cast with plenty of genre experience and the core situation, which carries an inherent appeal for fans of action-horror B-movies. Arrow’s new transfer is excellent and the disk is packed with extras – the usual Mastorakis featurette about the production, plus multiple on-set interviews and behind-the-scenes footage.

*

The Righteous (Mark O’Brien, 2021)

I pretty much knew what to expect from Nightmare at Noon. Mark O’Brien’s The Righteous (2021), however, was a complete unknown before I slipped the disk into my player. I’d mainly bought it because I was intrigued by the idea of a horror movie made in Newfoundland, a place I’d partly grown up in and which, while somewhat impoverished, seemed an unlikely site for disturbing stories. Certainly, I wasn’t aware of any movies or literature which leaned that way – past experience offered things like Peter Carter’s The Rowdyman (1972), Mike and Andy Jones’s The Adventure of Faustus Bidgood (1986) and Secret Nation (1992), Annie Proulx’s The Shipping News (1993), and various accounts of sea disasters.

In this context, Mark O’Brien’s first feature is quite disorienting, a bleak, black-and-white drama mixing horror and religion in ways which draw more on Ingmar Bergman (Winter Light [1963] might be a reference point) than the quaint culture of the outports rooted in a long-gone fishing industry. Taking place mostly in a remote house huddled in a winter landscape, this is a chamber piece about lives crippled by guilt which edges towards the supernatural, but never quite crosses over. Given that O’Brien is himself an actor, it’s not surprising that his script and direction give primacy to the performances, with Scott McClellan’s stark cinematography providing an atmospheric context for the drama.

Frederic Mason (Henry Czerny) is a former Catholic priest who left the Church and married Ethel (Mimi Kuzyk). They live in that remote house, grieving the death of an adopted daughter who was killed by a hit-and-run driver. There’s an uncomfortable visit from the girl’s birth mother, Doris (Kate Corbett), whose own grief clashes with theirs. And then one night, an injured stranger staggers to the house seeking help. There’s something not quite right about Aaron (director O’Brien); despite seeming helpless, he also seems vaguely threatening. As the night goes on, he reveals that he knows things about Frederic and Ethel and the death of their daughter.

And yet Frederic spontaneously decides to offer Aaron shelter – in fact, although he initially calls the police, when officer Mary Hutton (Mayko Nguyen) shows up at the door, he lies and says that Aaron is a nephew. The young man ingratiates himself with Ethel, growing closer to her even as Frederic becomes more suspicious and uneasy. The ebb and flow of emotions among these three gradually draws long-buried secrets to the surface – is Aaron a demon? an angel? Or is he just the illegitimate son of a young woman whom Frederic impregnated years earlier while still a priest, whom he abandoned as he abandoned the Church? More disturbingly, is he the driver who killed their adopted daughter, and if so was that a deliberate act?

Aaron’s arrival disturbs the complacency into which Frederic has settled, burying his guilt for acts which his religion identifies as sins; now he’s forced to confront those acts and the painful consequences arising from them. This disturbance of a life mired in lies and self-deception eventually culminates in intimations of apocalypse. While this suggestion of cosmic forces at work rests on the need to accept the religious elements of the story as reality – something which doesn’t convince me personally – the psychological drama remains effective thanks to the excellent performances, particularly from Czerny as a man tormented by the inherent conflict between his personal desires and failings and the unforgiving tenets of his religion.

The digital black-and-white image looks excellent on the disk, and along with a commentary from O’Brien and editor Spencer Jones there are almost four hours of interviews and featurettes covering the production in detail.

*

Croupier (Mike Hodges, 1997)

If the release of 4K restorations are anything to go by, Mike Hodges’ reputation was undergoing a kind of renaissance when he died in December at the age of eighty-nine. With restorations of Get Carter (1971), Flash Gordon (1980) and now Croupier (1997) – the first and third of these in just the past few months – plus Blu-rays of Pulp (1972), A Prayer for the Dying (1987) and Black Rainbow (1989) released in the past half-decade or so, only three of his nine theatrical features are still missing in hi-def. That’s not a big output over three decades from a filmmaker whose first feature was a landmark in British cinema and it’s difficult not to see the ups and downs of Hodges’ career, including chronic problems with producers and distributors, as at least in part of his own making. The films he did make are a mix of very personal projects and jobs for hire, which means that they don’t all fall into a clear auteurist body of work. Which is to say that he’s not easy to pin down, but at his best he was a masterful director, though his entire career – which included a fair amount of television work – was overshadowed by the acknowledged classic with which it began.

But even Get Carter received a mixed reception when first released, its bleak vision of England and its cold depiction of a ruthless and violent criminal who occupies the place of hero in a very sordid narrative greeted with distaste by some critics. While the criticisms were different a quarter-century later, his finest film since Get Carter was also poorly received. In fact, Croupier was so disliked by the people who funded it that it was barely released, destined to head straight to video until a friend of the director secured a U.S. distribution deal and it received a lot of ecstatic reviews from American critics. This, and a change of management at Film 4 back in England, finally saw it released theatrically in England several years after completion, but it never achieved the momentum it might have had if more sympathetically handled.

Croupier, Hodges’ penultimate feature, is very different from Carter. Rather than a brutal, highly active protagonist, its main character is passive, a still centre around which its oblique narrative revolves. And the England it depicts is very different, no longer a wasteland of failing industry and grinding poverty, but rather a country awash in the money and vacuous self-confidence of the post-Thatcher economic boom on the verge of the Blair years. The setting of a rather tacky London casino stands as a metaphor for the nation, awash in wealth but fraught with insecurity, greed constantly undermined by the fear of failure.

The script by Paul Mayersberg (who had notably provided previous scripts for Nicholas Roeg and Nagisa Oshima) does many things which common wisdom says it shouldn’t, beginning with the passive protagonist and compounded by the use of almost wall-to-wall voice-over. And yet it all works beautifully, creating tension and drama from what on the surface seems to be an almost total lack of action. The film is a character study which exists almost entirely inside the character’s head; we see the world only through his perception, filtered through his limitations which are compounded by an absolute certainty that he has complete understanding and control.

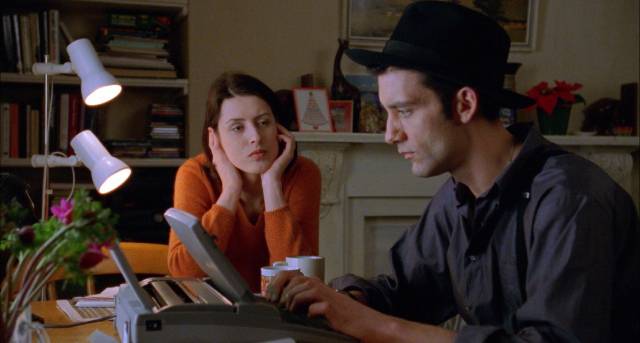

Jack (Clive Owen) is a would-be writer stuck in a creative block. He lives with Marion (Gina McKee), an ex-policewoman now working as a store detective, who loves the idea of living with a writer rather than with Jack himself. When he takes a job, she’s resentful that he no longer conforms to her romantic idea of him. That job, urged on him by his father (Nicholas Ball), is as a croupier at a small casino. Jack initially doesn’t want the job – he was born in a casino in South Africa where his father’s gambling had wrecked the family. It’s a world he knows all too well, particularly the dangers of compulsion and addiction. And yet, the need for some income and the atmosphere of the casino exert a powerful pull, appealing to his belief in his skills and his understanding of the psychology of the punters who come there with their illusions and the certain knowledge that they’ll inevitably lose.

One of Croupier’s real pleasures is its attention to detail, its depiction of a character performing a job with effortless skill. Owen’s Jack is an artist, whether running the roulette wheel or dealing blackjack, the camera equally attentive to his hands as it is to his eyes as he watches the players and interprets every minute change of expression. In a typical movie set in a casino, the focus is always on these players and the shifting currents of luck; but here we stay with Jack’s perspective as knowledgeable observer and interpreter, listening to the flow of his thoughts which express an almost godlike detachment and sense of superiority.

That voice becomes the expression of Jack the writer as he begins to transform himself into Jack the character in a novel, a character inspired by both his own experience and fellow croupier Matt (Paul Reynolds), a man lacking Jack’s sense of control, swept along by the amoral currents flowing through the casino, cheating and himself living the desperate life of a compulsive gambler. Jack is fascinated by Matt as a character but rather contemptuous of his lack of control. Yet he now has a subject which breaks through his writer’s block and when not at the casino, he works obsessively on a new novel. However, even this new commitment to his avocation can’t restore equilibrium to his relationship with Marion – with their clashing schedules, they barely see each other, and when she reads his work in progress she hates it, she hates the character, she hates what she sees Jack turning into, or rather what’s now being revealed about who he really is.

It doesn’t take long for him to be drawn towards other women who are embedded in the world he’s now immersed in – Bella (Kate Hardie), a tough and cynical croupier, and Jani de Villiers (Alex Kingston), a South African woman who loses money at the casino and who breaks through Jack’s protective armour with her vulnerability. Despite his detachment and his certainty that he’s always in control, he doesn’t realize that he’s being played. Jani tells him that the only way she can escape retribution from the violent people to whom she owes money is to enlist Jack’s help with a proposed robbery at the casino – he doesn’t have to do anything illegal, just get into a dispute with a belligerent player to create a distraction. And for that, he’ll receive a pile of cash.

By becoming involved with Jani outside the casino, he’s already broken the rules, so taking a cash advance from her is just another small step. There’s no real risk, or so he believes, not realizing that he’s rapidly violating his own rigid rule about never gambling himself. It’s at this point that arguably Mayersberg’s script breaks its own key rule – for a single scene, it steps outside Jack’s perception as Marion intercepts Jani’s phone call about the time of the raid on the casino. Thus, on New Year’s Eve, Jack is taken by surprise by a man who cheats at the roulette table and, when caught, starts a fight. But the robbery stalls as the police arrive, having been warned by Marion.

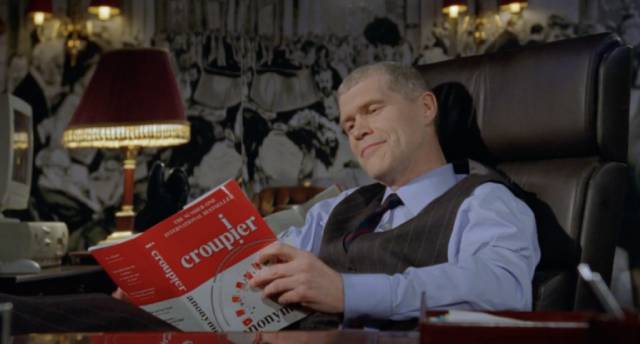

It’s an audacious move, what would normally be the climax fizzling in a moment to nothing. Chance and contingency rule in this world and Jack’s own sense of control is just as illusory as the belief in the power of luck to which the players cling. Jack’s book about the business, published anonymously, is a success, but he doesn’t give up the job; he’s as addicted to his role as croupier as the gamblers are to the chance of winning. Even when he knows how he was played and by whom, it doesn’t matter – he’s where he needs to be, doing what confirms his own sense of who he is.

In a way, Croupier is the Rosencrantz and Guildenstern of casino heist movies, all the action occurring out of sight of the minor peripheral character paradoxically placed at the centre of the narrative, a man convinced of his own autonomy and the power he wields yet utterly oblivious of what’s really going on around him and of the forces shaping his own actions. By accepted standards of movie storytelling it probably shouldn’t work, but between Mayersberg’s writing, Hodges’ attention to detail, capturing every psychological nuance of the character, and Owen’s compelling performance which somehow makes detachment and stillness just as gripping as Carter’s angry action, the film is as exhilarating as any well-made thriller.

Arrow’s edition offers an excellent new scan from the original negative. The clarity of the image makes it clear how audacious the design of the main casino set is – with the room surrounded by distorting mirrors, it’s impossible to see how Mike Garfath’s constantly moving camera is never glimpsed in the background. It must have been a nightmare to shoot!

The first disk includes two commentaries, an archival track with Hodges and a new one with critic Josh Nelson, plus engaging interviews with Mayersberg and actor Hardie, and an audio interview with Hodges recorded at a BFI screening of Croupier.

Mike Hodges: A Film-Maker’s Life (David Cairns, 2022)

The big extra, though, is the limited edition’s second disk with David Cairns’ Mike Hodges: A Film-Maker’s Life (2022). Shot during a single afternoon visit to Hodges’ home, this two-hour conversation (really a monologue) covers the director’s entire career, from his childhood through his national service in the navy to early days in television documentary and on through his filmmaking career project by project. At eighty-nine, Hodges’ memory remains sharp, and he offers detailed anecdotes and honest evaluations delivered in a lively, unpretentious manner. Although towards the end he does show some signs of diminishing energy, it’s an amazing display of stamina (I wish I had that kind of energy!). His affection for projects which didn’t receive a lot of critical appreciation suggest that these movies might be worth another look, while his accounts of producer interference make you wonder how much better a movie like A Prayer for the Dying might have been if it had been left in his hands. He also still seems bemused that he was hired to direct Flash Gordon, a movie for which he felt little affinity even when he was making it. His was an odd, somewhat unfocused career, but the level of craft in his movies is undeniable even if some of them were misfires (I confess I’ve never seen Morons from Outer Space [1985] and don’t have much inclination to go looking for it). I do recall being disappointed by his final feature, I’ll Sleep When I’m Dead (2003), but would be interested in seeing it again if it gets a new release.

The combination of a beautifully restored Croupier and Cairns’ excellent tribute to Hodges make this set, released in December, one of Arrow’s finest releases of 2022.

Comments