Death and madness from Indicator

Death of a Gunfighter (1969)

An interesting quirk of Indicator’s wide-net approach to cinema history is the company’s unearthing of a couple of little-known westerns from that genre’s most turbulent transitional year, 1969. Last year, they released Budd Boetticher’s final feature, A Time for Dying, and now they’ve brought out Death of a Gunfighter, like Boetticher’s film a movie I’d never heard of although the people involved in the production should have guaranteed it a more prominent place in history.

Here we have Richard Widmark giving a conflicted, elegiac performance as a man of the West whose time has passed, something akin to the outlaws in Sam Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch and John Wayne’s burned-out sheriff Rooster Cogburn in Henry Hathaway’s True Grit (both also 1969). It was also the year of George Roy Hill’s Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, which unlike these other movies represented a smug dismissal of Western mythology. Widmark’s Marshal Frank Patch would find echoes in Peckinpah’s The Ballad of Cable Hogue (1970), Don Siegel’s The Shootist (1976), even in Tonino Valerii’s My Name is Nobody (1973).

For most of the preceding six decades, the movies had accepted the cherished American idea of rugged individualism on the frontier, of strong determined men forging their own destinies in an unformed land. Even movies critical of the myth acknowledged its centrality to America’s self-image. But the upheavals of the ’60s had made that image no longer tenable, recognizing the crimes it had been used to justify as the dark secret lurking beneath the myth of progress and the expansion of “civilization”, a myth which could no longer support the cynical adventure of something like the Vietnam War. In 1962, John Ford’s The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance ends with the newspaper editor dismissing the true story of what had happened by saying “when the legend becomes fact, print the legend”, but by the end of the decade it had become too obvious that the legend was toxic.

Like The Wild Bunch, Death of a Gunfighter tries to capture this new historical awareness by placing its story at a particular transitional moment, a point early in the 20th Century when the West had been “tamed” and the tools of that taming had not only become redundant but were now a liability. The violence which had driven expansion now posed a threat to the order which had been established; what capitalism needed was social stability and in order to obtain it the past with its crimes had to be suppressed and a new, less mythical self-image forged. A key symbol of this transition here, as in The Wild Bunch and The Ballad of Cable Hogue, is the appearance of an early automobile, the modern wonder destined to replace the West’s iconic horse.

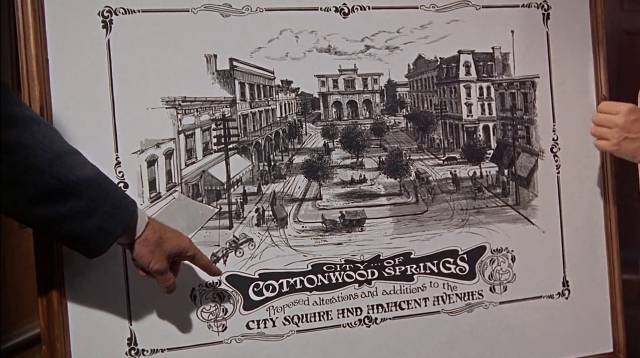

Frank Patch represents everything in that past which has now become inconvenient. He’s been the law in the small town of Cottonwood Springs for twenty years, maintaining order with his gun. As a symbol of violence, he presents an image which is no longer romantic and is now an obstacle to attracting investors from back East. The businessmen of the town want him gone, but he refuses to resign and, more problematically, doesn’t accept their right to fire him. Although they hold the community’s social and political power, these wealthy men fear Patch and his penchant for confrontation and violence. But when the Marshal kills a drunken man who tries to shoot him – the drunk is a weak, pathetic character who believes (rightly) that he was cuckolded years earlier by Patch – the whole town begins to turn against the lawman.

Although the script by Joseph Calvelli (based on a novel by Lewis B. Patten) is well-constructed, with finely-drawn characters, there’s an absence at its centre which becomes increasingly frustrating as the story plays out: there are suggestions that the members of the council have compromising secrets which are known by Patch and which he uses to exert his power over them, but except in one case late in the film, we never learn what they’re hiding. The suggestion is that this successful community, with its railroad and profitable businesses, is built on a corrupt foundation … and Patch somehow embodies that foundation. At one point, he’s called the town’s conscience – or, as Paul Duane puts it in his booklet essay, he’s the sin-eater, the man who takes on everyone else’s guilt so society can function. But having taken on those sins, this figure is shunned and despised, and as a constant reminder his presence becomes unbearable. The only solution is violent expulsion, with the entire town unified against Patch, who in refusing to leave willingly submits to a very public execution… Ironically, the town tries to rid itself of its violent past through an act of communal violence. (I don’t consider that a spoiler, given the title and the fact that the film opens with a coffin being loaded onto a train, then flashes back to the main story.)

There are other interesting nuances in script and execution. Widmark’s Patch is no upright hero facing corrupt opposition. He’s morally compromised and prone to sudden outbursts of violent anger, more often than not directed at those most sympathetic to him. Perhaps the most unexpected touch for its time is the casting of singer Lena Horne as saloon owner and brothel madame Claire Quintana, the woman closest to Patch, with whom she’s been involved in a long-term relationship, and whom, towards the end, he marries. At no point is any comment made about the implications of a bi-racial relationship, even though prejudice rears its head when county sheriff Lou Trinidad (John Saxon) is called in to remove Patch; his disgust with the council members is apparent and they respond with racial slurs, obviously resenting the fact that Patch had used his influence to install the Hispanic Lou in his position of authority. But its not just the businessmen – Patch himself dismisses Lou with a slur in yet another outburst.

Despite a crucial element of the narrative remaining obscured – what are those buried secrets? what is the meaning of the unspoken final confrontation between Patch and the priest, Father Sweeney (James O’Hara), which promises a revelation which doesn’t come? (as Patch turns away, the priest faces the altar and asks God’s forgiveness, but we have no idea what it’s for) – Death of a Gunfighter is a taut, revisionist character study which, like other Westerns of its time, re-examines and critiques a too-familiar genre in interesting ways. Supporting Widmark, Horne and Saxon are a cast of fine character actors – Carroll O’Connor, Kent Smith, Morgan Woodward, David Opatashu, Jacqueline Scott, Larry Gates, Dub Taylor, Royal Dano, Harry Carey Jr. – and there’s even some interesting camerawork. So why has it remained so obscure?

Perhaps the answer is simply because of the director credit. This was the first feature to be directed by Alan Smithee (or rather here Allen Smithee). This phantom auteur has long-since become something of a joke, so it’s startling to realize that he had a very particular origin. The original director was Robert Totten, a television veteran apparently hired on the recommendation of Don Siegel. Totten shot most of the movie, although he clashed continually with powerful star Widmark. After five weeks, Widmark forced the issue and had Totten fired, bringing in Siegel with whom he’d worked well the previous year on Madigan (1968). Siegel wrapped things up in another couple of weeks, doing his best to match what had already been shot rather than starting over. Because he felt his contribution was limited, he refused an on-screen credit; perhaps not surprisingly, Totten didn’t take credit either (although Neil Sinyard in an interview on the disk asserts that Widmark refused to allow any credit for Totten).

Given that the Smithee alias is notoriously used by filmmakers who feel that their work has been so compromised by interference from producers and distributors that it no longer has anything to do with their original intentions, this origin story is unexpected. These two directors apparently felt not that they didn’t want credit, but rather that they didn’t deserve it. And rather than the movie being an embarrassing mess that no one wanted to be associated with, it’s actually an interesting, well-crafted film with a consistent style, excellent performances and a focused dramatic trajectory which leads to a strong, almost tragic ending. But because of the absence of a familiar name to which it could be clearly attached, it seems to have fallen through the cracks.

Totten didn’t have any real profile as a feature director, so it might be tempting to see it as “a Don Siegel film” – it’s certainly a better film than Coogan’s Bluff (1968), which Siegel had just made before he was called in – but it seems that the majority of the film was shot by Totten. So no clear auteur. It’s amusing to see that early reviews praised the work of the unknown Smithee (including Roger Ebert) before the Director’s Guild revealed the secret of his identity (after which some reviewers looked for signs of Siegel’s directorial hand).

The technical presentation of the film is up to Indicator’s usual standard; like Boetticher’s A Time for Dying, it looks a little like a TV production – the town is a bit too clean and underpopulated – but there are striking visual moments, not least the climactic crane shot at the moment of Patch’s violent death. Probably the weakest element of the film is the overdone score by Oliver Nelson, who mostly worked in television; something more subtle would have been more effective.

The disk includes a commentary from C. Courtney Joyner and Henry Parke, the 22-minute interview with Neil Sinyard previously mentioned, and another 24-minute interview with Richard Dyer about the unusual casting of Lena Horne and the film’s anomalous place in her career. There’s also a 10-minute short film, Exercise No. One (1962), made by USC film students under the supervision of Fred Zinneman, in which Widmark plays a salesman driving through the desert who gets a flat tire and finds himself under fire from a crazed former soldier (Whit Bissell) who thinks he’s still at war. It’s a tense little piece which goes to a very dark place.

*

They Might Be Giants (Anthony Harvey, 1971)

Another new release from Indicator is much more problematic than Death of a Gunfighter, although there’s no ambiguity about authorship. Written by James Goldman (from his own play) and directed by Anthony Harvey, who had previously collaborated on the multiple-award-winning A Lion in Winter (1968), They Might Be Giants (1971) is a mess. Aiming for wistful, with a melancholy point about the disappearance of romance and adventure in modern life, it wavers between comic charm and strained whimsy before plunging into raucous vagary on the way to disappearing up its own backside … which is a pity, because it begins promisingly.

Why did I find this movie so irritating? It can’t simply be that it begins as one thing – a rather obvious narrative – and then shoots off in other directions, that original narrative discarded as if completely irrelevant. If it had stuck with the story, it would have been a fairly conventional movie, predictable but undoubtedly entertaining. What I found frustrating was what gradually replaces that story; Goldman and Harvey pile on such metaphorical weight that the fragile structure can’t support it – convention is replaced by vagueness and pretension.

Justin Playfair (George C. Scott, fresh from winning the Oscar for Patton [1970]) is a prominent New York judge who, in dealing with his grief after his wife’s death, has assumed the identity of Sherlock Holmes. Holmes’s attention to detail, his ability to deduce things from the most obscure clues, affords Justin a sense of control; his obsession with arch-foe Moriarty provides a malevolent agent responsible for the unbearable loss of his beloved wife. If there’s an evil actor behind everything that happens, then we’re not at the mercy of contingency.

Meanwhile, Justin’s brother Blevins (Lester Rawlins) is being blackmailed by the mysterious Mr. Brown (James Tolkan) and he needs money. If Justin can be committed, Blevins will assume control of his brother’s estate and have enough to pay off the blackmailer. The impatient Mr. Brown is only willing to wait a short time and if Blevins’ plan fails, he’ll have Justin killed to facilitate transfer of the estate. And so Justin is taken to a psychiatric clinic for evaluation.

The venal Dr. Strauss (Ron Weyand) assigns one of the staff, a middle-aged doctor, to diagnose Justin – a classic paranoid schizophrenic – and she’s fascinated by the case. The initial session, in Justin’s study-cum-lab, is prickly; she’s wasting his time as he analyzes clues to Moriarty’s whereabouts. But then his attitude abruptly changes because he discovers that the doctor’s name is Watson – fate has handed him confirmation of his assumed identity. The game, as they say, is afoot and he drags Dr. Mildred Watson (Joanne Woodward) off on a quest to find and stop the arch-villain.

There have been numerous comic treatments of Sherlock Holmes; the character is both satisfying as conceived by Conan Doyle, but also ripe for parody and pastiche. His ability to penetrate mysterious events and uncover motives and causes by pure reason makes him the Platonic ideal of the detective. Detective stories by their nature are a kind of game, the goal of which is to uncover a reassuring sense of the world as something meaningful, something it’s possible to grasp and understand. The potential for comedy naturally arises from those deductive faculties being applied to coincidences and non sequiturs, constructing phantom plots and conspiracies, which in turn, though patently absurd, might prove to be real after all.

And initially this is the game that They Might Be Giants plays. One nonsense clue leads to another and those around Justin begin to fall into place within his delusion. Mr. Brown assumes the position of Moriarty; the blackmail of Blevins may eventually be uncovered and the plot to dispossess Justin exposed … but gradually that trite narrative core crumbles. Each new encounter becomes more random and arbitrary and the focus falls more on the relationship of Holmes and Watson, the latter’s professional interest becoming more personal. It’s not an absurd mystery so much as a romantic comedy about two lonely people at odds with a depressingly material world in which everything is predicated on monetary exchange and exploitation.

And, as the title has already flagged, this is not so much a pastiche of Sherlock Holmes as it is a reworking of Don Quixote. Justin is a displaced romantic, unwilling to accept that romance has vanished from the world. His Moriarty mutates into an imaginary giant, like Quixote’s windmills, to be confronted and defeated in the name of a chivalry disdained by the mean people who populate this world. Justin’s form of madness is deemed a noble alternative to acquiescence to crass materialism; and Watson, initially wanting to study and analyze that madness, eventually joins Justin in his fantasy. Better to be mad than live in dull reality, and more romantic to expend your energy on fighting imaginary enemies than on solving real problems. (In the past decade, we’ve had ample evidence of just how well that strategy works!)

Even this alternative narrative, though thematically dubious, might have been satisfactory, particularly given Scott and Woodward’s considerable on-screen chemistry. But they’re adrift in a random collection of scenes which lead nowhere and increasingly seem to bear no relevance to the theme. There’s a diversion to an elderly couple’s rooftop garden in a derelict building, where they have hidden away for decades growing fruit and vegetables and practising topiary. There’s an embarrassing sequence in which Watson fumbles preparations for a dinner in her shabby apartment, a TV-sitcom-level depiction of a sad spinster’s domestic incompetence. And then finally a long, tedious, unfunny stretch in which Holmes and Watson walk through New York at night gathering together all the lost and damaged souls they’ve encountered, like the Avengers coming together to confront the super-villain … arriving at last in a bleak, snowy park where Justin turns to his hopeful followers and asks if anyone knows why they’re there and what they’re doing, receiving only confused, blank stares in response.

Leaving them all behind, he and Watson descend a spiral staircase into underground tunnels, emerging from a manhole in front of a huge, virtually deserted supermarket which, somehow, the clues have led them to. Expecting to find Moriarty in the store’s meat freezer, the pair are finally faced with the possibility that it really has all been a delusion … at which point Blevins and Dr. Strauss arrive with an army of cops who swarm into the store to capture Justin and Watson and drag them off to the clinic. But wait … somehow the misfits appear and attack the police in a massive food fight … but they’re overwhelmed by the authorities’ superior force … until Justin gets on the PA and starts announcing amazing deals which even the cops can’t resist, enabling the misfits to escape.

Slipping away, Justin and Watson arrive in Central Park and wait at a tunnel entrance for the arrival of Moriarty. Justin can hear something … the sound of horse’s hooves and the jangling of a bridle … Watson hears nothing at first, but then she can … she’s finally, fully entered Justin’s romantic delusion and together they await the arrival of the phantom menace which will make their lives and their love meaningful because, you know, dreams are so much better than reality and it’s preferable to submit to madness than face the world as it is.

How we arrive at that dubious point via all those disconnected and tediously unfunny sequences is the movie’s biggest mystery, how it wastes the considerable talents of its two stars its major crime. The execution is such a mess because it’s such a conceptual misfire. The narrative with which it begins (and which it quickly abandons) simply can’t support its thematic pretensions. Yet Indicator have done their best to argue that it’s something of a misunderstood masterpiece, with their usual fine transfer accompanied by two commentaries – an archival one from Harvey and film restorer Robert A. Harris, and a new one from Barry Forshaw and Kim Newman – plus an archival featurette and a new interview with Kim Newman about the history of Holmes on film. There’s also a booklet with an admiring essay from Chloe Walker and a lengthy piece about Harvey’s career and his problems with this production, which was re-cut by the distributor against his wishes (though from the comments provided, it sounds as if what was cut was mostly just more random scenes rather than anything to do with any core narrative). There’s also a summary of the film’s decidedly mixed, though predominantly negative, critical reception.

Comments