Serendipity at the mall: disk discoveries from England and Australia

We all cling, to some degree, to the things that shaped us. External changes force us to adapt, but they never take us away completely from those original influences. That’s no doubt why my sense of cinema is rooted in what I saw on television from an early age – late ’50s and ’60s – and then in theatres from the mid-’60s through the ’70s. Because of the way TV functioned back then, what I saw reached back decades to encompass a lot of what had been made through the medium’s first seven decades. I’m grateful for the expansive sense of cinema I gleaned from this … and can’t help but be puzzled by the disinterest and lack of curiosity about film history that seems so much more common in succeeding generations. This is what probably makes me seem like a cranky old guy stuck in the past when I just can’t muster any enthusiasm for so much of the popular entertainment which has been churned out over the past two or three decades, seeming to lack so much of the depth and range of cinema’s first three-quarters of a century.

I still went to see new movies through the ’80s, ’90s and ’00s, though in declining numbers as the great old theatres closed and everything was channelled into characterless suburban multiplexes. But when home video flourished through those decades my habits began to change; increasingly, I was renting movies on VHS and watching at home, and when in the mid-’90s I began to collect, more often than not I was reaching back into the past, revisiting movies I’d seen years before and catching up with an ever-expanding history which was being made accessible in a way it had never been before. That nascent collection – first on VHS, then towards the end if the ’90s on laserdisc, and beginning around the turn of the millennium on DVD – became my own personal on-demand service, with a wide range of movies at my fingertips to revisit at will. With distributors eagerly profiting off their century-spanning catalogues, I became immersed in the art and entertainment which had most appealed to me since earliest childhood. I did still consume quite a lot of new movies, though my preference had shifted decisively to that collection at home – and that was dominated by titles from the past.

To someone who was born in the past thirty years, who came of age in the past decade or so, my experience must seem quite alien. With the decline of television and the rise of the Internet, everything has changed radically and movies are accessed in very different ways. Streaming has become a major factor in distribution, with theatres leaning more than ever into large-scale spectacle to compete, just as the industry had developed widescreen, stereo sound and gimmicks like 3D in the early 1950s to compete with television. But the seeming expansion of accessibility with the proliferation of on-demand channels has had some counter-intuitive effects; major corporations have partitioned off their own product into dedicated services, requiring multiple subscriptions, while a decline in interest for – and thus the profitability of – older movies means that a sense of history is being lost. My friends who have taught film studies over the past few decades have been frustrated by students who are mostly unaware of anything made before they began to go to movies themselves, and have little interest in learning about where their preferred entertainment came from.

The first decade of movies-on-disk was something of a golden age for someone like me, but with a market reaching saturation point the big companies began to lose interest – fewer restorations of catalogue titles, the disappearance of substantial extras – and the appearance of viable streaming technologies gave rise to perennial predictions of the disappearance of physical media. This seemed a possibility as actual stores were faced with increasing on-line competition. Where there had once been many stores to go and browse in, movie (and music) sections were visibly shrinking in big chains like Future Shop and Best Buy; chains like HMV and A&B Sound began to close locations and eventually disappeared altogether. Those of us still in the grip of the collector compulsion were increasingly forced to go on-line, though that lacked the immediate visceral pleasure to be gained from browsing shelves and making unexpected discoveries – in my most intense period, say from 2000 to 2010, I would spend hours in stores and walk out with bags full of DVDs, often dropping $400 at a time, week after week, but that’s no longer an option.

And yet, despite everything, disks haven’t vanished. In fact, if anything, options today seem better than ever. What happened was that smaller companies appeared which would license titles from the big companies which had lost interest in their own holdings. The broad commercial model of the earlier years morphed into a collector culture, once again reaching back into history but focused on a range of niches which give each company its own particular identity. Some of these companies are firmly established and have been around for years, others seem to pop up suddenly, gradually establishing a foothold, sometimes vanishing just as quickly. This landscape offers the possibility of new discoveries, making apparent that even after forty odd years of home video there is still much to unearth. As I’ve mentioned many times here, I do most of my buying these days at the dedicated sites of these companies – the BFI, Criterion, Arrow, Severin, Vinegar Syndrome, Shout! Factory, Synapse, Ronin Flix, 88 Films, 101 Films, Kino Lorber, Indicator, Cauldron, Eureka – or at aggregate sites like Unobstructed View and Diabolik DVD, which carry many of these labels. Most of these companies have wisely established their own marketing models which make it possible to avoid Amazon almost completely.

But for all the benefits of this evolution, the loss of physical stores is still sadly felt – here in Winnipeg, we were reduced to three outlets of the Canadian chain Sunrise Records, and a couple of months ago I went to the one closest to me only to find it had closed without warning two days earlier (I’ve since learned that this was a lease issue and the store might be back once a viable space opens up at the mall – but it was a sign of just how precarious the situation is). Beyond those stores, there are a couple of very small independents, the one I occasionally visit called Entertainment Exchange in the Grant Park mall (about a forty-minute walk from where I live), and another much less convenient called Planet of Sound on Henderson Highway. These are anomalies, selling music and movies in a combination of new and used disks, offering credit if you bring in something to trade.

On my latest trip to Entertainment Exchange, having accumulated a bag full of DVDs and Blu-rays to trade (ones I’d replaced with upgrades over the past few months), I got more credit than expected, so after browsing the import section I grabbed a couple of Australian releases – one from Umbrella, one from an unfamiliar company called Imprint – plus a release from a new British company I’d already been keeping an eye on called Radiance, but hadn’t yet taken a chance on. These were all new copies; I spent the rest of my credit on a couple of used items – slices of ’80s cheese in an Arrow limited edition and a Vestron Video Collector’s Edition from Lionsgate. I’m happy to say that although these all added up to about twenty bucks more than the credit, the owner waived the difference, so they cost me nothing.

*

Sons of Steel (Gary L. Keady, 1988)

I wavered on Umbrella’s Collector’s Edition of Gary L. Keady’s Sons of Steel (1988) because 1) it was very expensive and 2) I knew nothing about it. But I couldn’t help returning to it repeatedly as I browsed – an ’80s metal musical sci-fi comedy definitely appealed to me. I chatted with the owner about it and he explained the high price – it was a limited edition which came with some swag (a poster and lobby cards, a Pocket Nuclear Shelter Tote Bag, and a sheet of stickers) which had meant that he was hit with customs charges. Still, he offered to drop the price ten bucks (it pays to be a regular customer who always brings in good quality items for trade). Even so, I didn’t make a decision until I’d looked at everything else.

Is Sons of Steel a good movie? Perhaps that’s an irrelevant question. It’s the kind of movie that rests on its ability to appeal to a niche audience and, most importantly, on the quality of the music. I’m not an authority, so I checked with a musician friend and he agrees that the soundtrack (included on a CD) isn’t really metal – it’s more like ’80s anthemic arena rock (a touch of Meatloaf), with echoes of Richard O’Brien on songs like “Mr. System” – but I like it and that goes some way towards mitigating the movie’s shortcomings in other areas. I’d happily put it on the shelf with Walter Hill’s Streets of Fire and James Fargo’s Voyage of the Rock Aliens (both 1984).

Keady had been a music producer, but when he tired of that business, he turned to movies. After making the short Knightmare (1984), he tackled his first (and only) feature, this musical set in a future Australia under fascist rule, in which rocker Black Alice is in opposition to the dictatorship. The narrative is, well, murky. The world is in a mess because of a nuclear disaster involving the collision of a ferry with a nuclear submarine in Sidney harbour; that ferry was full of protesters, including Black Alice and his buddies. Warned by his future self, Alice has to try to stop the protest and avert the disaster…

Keady and his collaborators aren’t much concerned with the story; it’s just an excuse for Rob Hartley as Black Alice to belt out a series of songs. (Black Alice was the name of a metal band headed by Hartley, which broke up after recording their debut album, Endangered Species, in 1983; Keady, who had produced the album, brought Hartley back and reconstituted the band for the movie.) Although Sons of Steel has some pleasingly grungy production design by the great Graham “Grace” Walker, shot on 16mm by cinematographer Joseph Pickering, which gives it a strong post-apocalyptic B-movie ambience, I was a bit disappointed on my initial viewing because Keady doesn’t give a lot of visual energy to the musical sequences – but I’ve been listening to the soundtrack quite a bit and will watch the movie again when I get it back from the friend I lent it to, so am open to revising my opinion.

Given the source (a 35mm blow-up print), the image is rather dark and grainy, but that suits the material, so it’s not an issue. In addition to the soundtrack CD, there are some extras to provide context, including the short Knightmare, which is like a trial run for the feature, and an almost forty-minute making-of, which is essentially a monologue from Keady in which he talks about the film’s genesis, the problems of shooting on a low budget, and the release. He’s quite engaging. There’s also a fifteen-minute clip from MTV covering the premiere, with sound bites from cast, crew and audience members; half an hour of low-quality behind-the-scenes material shot on video; a fourteen-minute clip with a couple of movie critics on TV evaluating the film (both give it 3 out of 5); plus a couple of music videos.

There’s also a fat booklet containing an excerpt from volume one of a book series set in the same fantasy world as the movie.

*

Conquest of Space (Byron Haskin, 1955)

Imprint is apparently a relatively new label based in Australia and New Zealand. A glance at their website shows a wildly random collection of titles, making it difficult to get a handle on what if anything their intentions are – TV shows (old and new), indie films and mainstream entertainment, cult titles, various genre movies going back to the ’40s and ’50s – and because their releases are limited editions, many are already out-of-print. Some things did catch my eye (I just ordered their two-disk sets of Gillo Pontecorvo’s Burn! [1969] and Walter Hill’s The Warriors [1979], which thankfully includes the original theatrical cut as well as Hill’s disastrous director’s cut, plus Barbet Schroeder’s Barfly [1987], Mike Hodges’ I’ll Sleep When I’m Dead [2003], David Lynch’s The Straight Story [1999] and a 1946 B-movie called The Catman of Paris), and I’ll revisit for a closer look at some point. But what brought the label to my attention was finding a copy of their edition of Conquest of Space (1955) at Entertainment Exchange.

This is by far the weakest of the four collaborations between director Byron Harkin and producer George Pal, which began spectacularly with The War of the Worlds (1953), followed by The Naked Jungle (1954), and ended with the odd but interesting The Power (1968). Conquest of Space was intended as a follow-up to Pal’s influential Destination Moon (1950), a docudrama rooted in plausible science. And like that movie, it suffers from serious weaknesses of dramatic conception. Based on technical books by rocket scientists Willy Ley and Wernher von Braun projecting ideas about space travel, the script cobbled together by Philip Yordan, Barré Lyndon, George Worthing Yates and James O’Hanlon is a collection of genre cliches played out by cardboard-thin characters which were already overly familiar even that early in the ’50s sci-fi cycle.

There’s the crew of military stereotypes – a hard-nosed General (Walter Brooke) who takes command of what was intended to be a moon mission which gets diverted to Mars; the General’s son (Eric Fleming) who wants out to live his own life but is helpless against the old man’s domination; a no-nonsense scientist (William Hopper); and an insufferably dumb enlisted man (Phil Foster), brought along for comic relief. We get the usual bits of business – food is just nutritional pills, technical problems require a space walk, acceleration distorts actors’ faces, a sudden meteor shower causes damage – but two things in particular sink the movie.

The first is the script’s sole attempt to inject “drama” into the proceedings by having the General succumb to religious mania – apparently we were never supposed to leave Earth and invade God’s realm, so he tries to sabotage the ship. But since he outranks everyone else, the crew can’t just remove him from command … the fake tension is incredibly tedious.

But perhaps even worse are the movie’s technical failings, which are more apparent than ever in hi-def. George Pal’s biggest asset in many of the films he produced (and occasionally directed) was his grasp of special effects techniques, both physical and optical. Even today, what he and his crews accomplished in The War of the Worlds, When Worlds Collide (1951, excepting that final matte painting), The Naked Jungle, The Time Machine (1960), 7 Faces of Dr. Lao (1964) and others can be appreciated for both their design and their execution. By comparison, Conquest of Space is an embarrassment. But this wasn’t really Pal’s fault. Paramount, which produced the movie, insisted on reining in the budget, so many of the optical effects remained unfinished – some elements have unstable edges or are semi-transparent so you can see stars through the ship or the characters floating in space; models are inadequately detailed and poorly lit so they look like kids’ toys hanging on strings. Things were so bad that Pal’s reputation suffered for several years.

This is a case of improved digital technology doing a disservice to the movie – the transfer is vivid and colourful and it displays every flaw in painful detail. But Imprint has provided an array of extras to compensate – two commentaries, one by Pal’s biographer Justin Humphreys and a second from Kim Newman and Barry Forshaw, which together cover pretty much every detail of the production, its place in both Pal’s and Haskin’s careers and the movie’s place within the genre. There’s also a 37-minute featurette about Haskin’s career and another brief featurette with illustrator Vincent de Fate about the science underlying the movie. All of this makes the disk a worthwhile acquisition despite the shortcomings of Conquest of Space as a movie.

*

Phantom of the Mall: Eric’s Revenge (Richard Friedman, 1989)

All I knew about Richard Friedman was that he had directed the cheap slice of slasher self-parody Doom Asylum (1987), so I didn’t really have any expectations for Phantom of the Mall: Eric’s Revenge (1989), but there on the shelf was a used copy of Arrow’s two-disk Limited Edition and, on impulse, I added it to the little pile. As suggested by the title, this is essentially a reworking of Phantom of the Opera set in a suburban shopping mall. Somewhat misleadingly, the subtitle suggests that it’s a sequel – it isn’t. But it turns out to be a fairly effective little horror movie, still bearing a few traces of slasher influence, but closer to an updating of the traditional Gothic tale.

With the new mall ready to open, we’re immediately introduced to a masked figure lurking in maintenance corridors and air-conditioning ducts. He slips into a store to steal some clothing and a mannequin’s head (the latter intended to provide a mould for the mask he’ll wear for most of the movie); spotted by a security guard, he strikes quickly and drags the body away, the first in a collection which will accumulate as events unfold. But at this point, we don’t know who the Phantom is.

Next, we meet Melody (Kari Whitman), a girl applying for a job at the mall, still struggling with the loss of her boyfriend Eric (Derek Rydall) in a suspicious fire a year earlier. She attracts the attention of reporter Peter Baldwin (Rob Estes), who’s covering the mall opening, taking pictures of Mayor Karen Wilton (Morgan Fairchild) and developer Harv Posner (Jonathan Goldsmith), whose obnoxious son Justin (Tom Fridley) creepily hits on Melody. With all the characters in place, Peter and Melody team up after she’s attacked in the parking lot by an unknown assailant and saved by the mysterious Phantom. Together, they set out to investigate, a task which leads back to the fatal fire.

The movie’s origins in the Reagan era are signalled by the corrupt business practices behind the development of the mall and the collusion between Posner and Wilton … no surprise that the fire was just one event in their shady acquisition of the land necessary for the development, or that Eric didn’t actually die, but was hideously scarred by the flames. As in the source story, Eric aims to bring Melody into his underground world and works to eliminate everyone who stands between them, while also getting revenge for his own suffering.

Friedman’s work here is much more polished than in Doom Asylum; naturally, there’s an element of comedy (mostly supplied by Pauly Shore as Melody’s buddy Buzz), but it’s largely played straight, making it a satisfying throwback to an older style of horror. It also, like George A. Romero’s Dawn of the Dead (1979), sees the inherent darker side of the shopping mall as a temple of capitalism, the sunny face of consumerism built on a hidden complex of cruelty and exploitation.

And once again, we get a collection of disk extras which cast the movie in a different light. The making-of features interviews with co-writers Scott Schneid and Tony Michelman who explain at length that their version was taken over by producer Charles W. Fries, handed to another writer (Robert King) to make it more conventional, and then assigned to Friedman. Of course, from this perspective it appears that the movie is a bastardized version of something much more ambitious (like Gary Sherman’s Dead & Buried); it would be necessary to read the original script to say whether that version might have been better, or merely different – and Arrow have included that as a BD-ROM extra, so perhaps I’ll get around to taking a look at some point. As it is, we have the film as released and that’s actually not too bad.

The first disk also includes a commentary, some audio interviews, alternate and deleted scenes, and an interview with Joe Escalante of The Vandals about how the punk band came to create the movie’s theme. The second disk contains the television edit (some extra scenes but all the gore, nudity and swearing eliminated) and a combined cut incorporating the TV scenes into the theatrical version.

*

The Wraith (Mike Marvin, 1986)

Slicker than Phantom of the Mall, Mike Marvin’s The Wraith (1986) is also a teen revenge movie, though this one is explicitly supernatural. Overage high school kids in a small town are oppressed by psychotic bully Packard (Nick Cassavetes, son of John Cassavetes and Gena Rowlands) and his gang. Packard’s favourite pastime is challenging kids to road races with ownership of their vehicles as the prize. Since he’s a cheating scumbag, he always wins. A while back, he challenged the boyfriend of Keri (Sherilyn Fenn, a few years before showing up as Audrey Horne in Twin Peaks and the fetishized victim in Jennifer Lynch’s Boxing Helena [1993]) and he made sure his rival died in a crash; now he treats Keri as his personal property.

Things begin to change when a new guy (Charlie Sheen) rides into town on a motorcycle and Keri is immediately attracted. At the same time a sleek car mysteriously appears, its windows darkened to conceal the driver, and Packard wants it – so one by one his gang members challenge the mystery driver to races which end with them dying in fiery crashes. Local cop Loomis (Randy Quaid) wants to get to the bottom of the rash of deaths and Packard wants to seize Keri back from her budding romance with the new guy, who – no surprise – is her former boyfriend back from the dead and occasionally transformed into the flashy car.

The Wraith hits the expected notes of a teen revenge movie with the added element of high-speed chases on precarious mountain roads. Entertaining in its generic way, it’s unsettling to learn from the disk’s collection of cast and crew interviews that several crew members died in a crash when a camera car lost control while shooting one of those chases. No movie is worth dying for, but it seems worse when it’s a disposable piece of entertainment like this. On a lighter note, Clint Howard as Packard’s mechanic sports an amazing haircut (possibly inspired by Jack Nance’s look in Eraserhead [1976]).

*

A Woman Kills (Jean-Denis Bonan, 1968)

Having loaded up on genre titles, I aimed for a little more intellectual heft with A Woman Kills (La femme bourreau, 1968) by an unfamiliar director working in the context of the nouvelle vague as that movement intersected with the political turmoil of the late 1960s. This short feature was shot in May 1968 during the uprisings in Paris, with director Jean-Denis Bonan and his collaborators taking time during production to film the protests and the state’s violent response for the documentary Le joli mois de mai (1968). Bonan was a politically active documentarian making his first dramatic feature – something for which he faced some criticism, since fiction is a kind of betrayal of reality.

The resulting film, however, is far from conventional, deconstructing fiction and saturating it with documentary elements. In fact, it proved so unclassifiable that despite the efforts of powerhouse producer Anatole Dauman (who had worked with Alain Resnais, Chris Marker, Jean-Luc Godard and Robert Bresson among others) it was impossible to secure distribution and the film remained unfinished until 2014 when Francis Lecomte stepped in to finance a restoration of the materials and completion of the editing and sound mix.

On a first viewing, A Woman Kills is bewildering. Bonan makes few concessions to the audience and viewers are left to piece together what is happening as best they can from the fragmentary information provided. Over the opening shots – a claustrophobic hand-held tracking sequence through a narrow stone passage – a detached voice tells us that a woman has been executed for the brutal murders of several women; this voice goes on to provide background details about each character we meet with a traditional voice-of-god documentary authority.

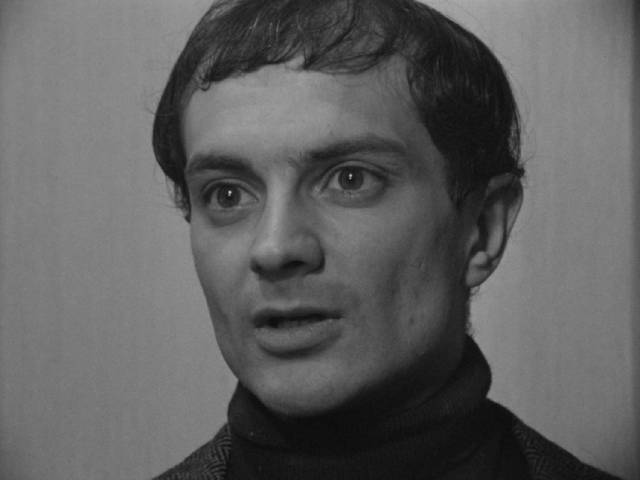

These characters include Louis Guilbeau (Claude Merlin), the executioner, as he leaves the prison, and detective Solange Lebas (Solange Pradel), who is connected with the case. Despite the apparent murderess having been executed, the crimes continue – either there’s a copycat or the wrong person was punished. But this all sounds more straightforward and linear than it is in the film. Louis and Solange become involved in a relationship. It becomes apparent that Louis has issues with his sexual identity and, disguised as a woman, is apparently killing prostitutes, perhaps inspired by the woman he executed.

A Woman Kills is steeped in ambiguity, the impossibility of any definitive knowledge about events and motives frustrating our need for clarity and resolution. It is also problematic – as explored in the commentary by Kat Ellinger and Virginie Sélavy (who also provides an introduction) and a booklet essay by Cerise Howard – for its treatment of gender ambiguity as a dangerous condition which triggers violence, linking the film to a strain of mainstream horror running from Psycho (1960) through The Silence of the Lambs (1991) and beyond. There’s a tension within Bonan’s movie between the radical deconstruction of the genre narrative and the regressive attitude towards sexuality. What may have seemed radical and transgressive in 1968 now appears uncomfortable in a completely different way, particularly given the current climate of hysterical reaction to the very idea of difference. A Woman Kills is an interesting artifact of its time, marked by intriguing and at times radical formal strategies and visual techniques, while its narrative content presents irresolvable contradictions.

The Radiance Blu-ray is an impressive package which provides context and useful analysis of the film. Along with the introduction and commentary, there’s a 37-minute featurette about the film’s production and its rediscovery, and Bonan’s career (interestingly, in addition to his progressive documentary work, he collaborated with Jean Rollin a number of times). There are also five short experimental films (totalling eighty minutes) made between 1962 and ’67, including Sadness of the Anthropophagi (1966) which was deemed so offensive that it was not only banned in France but also forbidden an export license so it couldn’t be shown anywhere in the world. Bonan managed to save it from complete destruction and it’s been restored along with the feature and the other shorts. Whether it was banned for its scatological content or because of its harsh critique of capitalism, it’s fascinating to consider how dangerous the authorities deemed it on the eve of what would prove to be an abortive revolutionary movement just a year or two later.

In the short, an unemployed man takes a job in a restaurant where the bourgeoisie gather to eat literal shit. His work consists of perching above a large tank into which he defecates, a worker producing products for consumption in a system built on the exploitation of his class. He eventually shits himself to death, a disposable component of the system. The very obvious metaphor remains pertinent, but it’s hard to believe it was once considered dangerous.

*

This post has been my somewhat long-winded celebration of an experience which has become all too rare; the pleasure gleaned from walking into a store with no particular aim or expectations, and the serendipitous discovery of a handful of interesting items I may never have stumbled across on-line … with the added satisfaction of immediate gratification. I headed home with my new acquisitions instead of having to wait weeks for them to arrive in the mail. And with my store credit from the disks I traded in, they didn’t cost me a cent. Does it get any better than that?

Comments

I also lament the loss of brick and mortar stores that sold movies. My journey as a collector mirrored yours fairly closely. I started out with Betamax- my first purchase was A Clockwork Orange. Next it was VHS, followed by laserdisc. I believe Blue Velvet was one of my first laserdisc purchases. Dvd, HD DVD and finally blu-ray. I never got into 3D blu-ray or 4K blu-ray. No need.

I’m glad you still have the ability to trade duplicates for store credit. That no longer exists in my area- the Niagara Region in southern Ontario. About a year ago the last video store- That’s Entertainment- closed down and for a month or so, they sold off their stock. The best item I grabbed was the Criterion Picnic at Hanging Rock dvd. I’m sure the store staff had first dibs at the really nice Criterion’s and collector’s items.

As usual I enjoyed your reviews and your trip down memory lane.

I can seldom remember “firsts”, but some key laserdisks were The War of the Worlds, Brazil (Criterion box) and Robinson Crusoe on Mars (also Criterion). Strange to look back and realize how much I was willing to pay for them (I think Brazil was around $170). I do recall my first DVDs and Blu-rays though – when I bought my first DVD player, I picked up copies of the South Park feature and my first Jean Rollin (The Living Dead Girl). And when I bought my first Blu-ray player, it came with a free copy of Christopher Nolan’s The Dark Knight – something I wouldn’t normally have bought, but it was actually in the box the player came in.