Grefé, Shatner and the resurrection of Impulse (1974)

There was much to enjoy in He Came From the Swamp, Arrow’s 2021 Blu-ray collection of movies made by William Grefé between 1966 and 1977, but Daniel Griffith’s accompanying feature-length survey of Grefé’s career made you realize that there were some things missing, that there was more to the filmmaker than even the seven features in the set showed. In addition to the racing pictures with which Grefé’s career began, two particular missing features stood out in the documentary.

Now, thanks to Grindhouse Releasing, that gap has been filled with a new two-disk set, which includes three features plus a huge quantity of supplementary material. This release, built around Grefé’s 1974 feature Impulse, provides a broader picture of the director’s work than the Arrow set suggested – in fact, Grefé seems to take the Arrow set to task in one of the new release’s interviews by expressing his irritation at being associated with “the swamp”, as the films he shot in Florida’s bayous comprise only a part of his output.

I’ve been waiting for this Grindhouse release for more than a year-and-half, since Grefé mentioned that it was in the works in a comment he posted on my review of the Arrow set in January of last year, and it more than satisfies such a lengthy anticipation. Impulse is not only one of the director’s best movies; it also provides a missing piece in the filmography of William Shatner, who himself has had a much more varied career than he’s usually given credit for.

Although most identified with Captain James T. Kirk, Star Trek comprises only a tiny fraction of Shatner’s work (less than a dozen of his 250 or so credits); and although Shatner himself has embraced the common impression that he’s a somewhat comical figure – the oddly unnatural cadences he used as Kirk have long been affectionately mocked even by fans, and his recording career has courted ridicule – his early career included roles in Richard Brooks’ The Brothers Karamatzov (1958), Stanley Kramer’s Judgment at Nuremberg (1961) and Martin Ritt’s The Outrage (1964) before his extensive television work led to a lot of genre roles in the ’70s – Steve Carver’s Big Bad Mama (1974), Robert Fuest’s The Devil’s Rain (1975), John “Bud” Cardos’s Kingdom of the Spiders (1977) – before returning to Star Trek on the big screen in 1979.

What is sometimes obscured by the dominant image of Shatner is that not only is he a pretty good actor, but that he has also occasionally made some interesting career choices. He was excellent in Roger Corman’s The Intruder (1962), in which he plays an opportunistic racist agitator stirring up resistance to the Civil Rights movement in small Southern towns; and he brought gravitas to Leslie Stevens’ Incubus (1966), a genuine oddity which grafts Bergmanesque imagery onto an allegory about war and sin, all played in Esperanto.

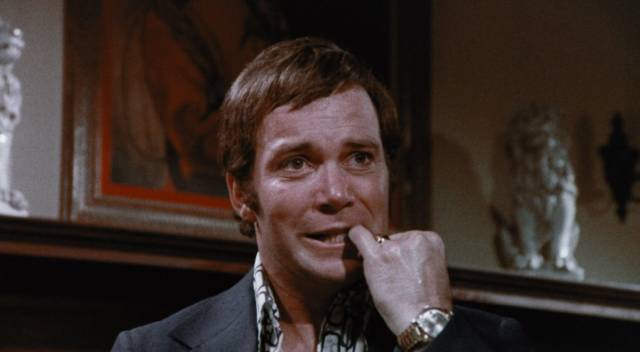

Giving Shatner the lead in Impulse was inspired casting, and according to Grefé it resulted from a chance encounter in an airport while he was preparing the production. Although small-town con-man and occasional killer Matt Stone seems the antithesis of the noble Kirk, the character draws on the actor’s career-best performance as Adam Cramer in Corman’s gritty and timely realist drama (the only film, according to Corman, on which he ever lost money). Like Cramer, Stone is all surface charm concealing a dangerous hidden pathology.

In the film’s prologue, set as the country celebrates the end of World War Two, young Matt sees a drunken soldier abusing his mother (possibly a prostitute, though this isn’t entirely clear) and kills the man with a souvenir samurai sword. From glimpses of Matt’s memories when we rejoin him years later, we learn that he had been locked away for years, probably in a mental hospital, emerging as an adult as a predator with serious sexual hang-ups. In the title sequence, he’s in a bar watching a belly dancer; his expression is intense, but arousal seems to be mixed with something else, something undefined but vaguely threatening.

When he leaves the bar with the dancer, we expect the worst, but he actually just takes the woman to his motel for sex. However, another woman follows them and the next day confronts him about the encounter. This is Helen (Marcia Knight), an older woman Stone has been stringing along because she has money. As they argue in her car, she accuses him of cheating on her with a “tramp”, the same epithet the soldier had used on his mother, and Stone is swept away by anger, strangling Helen without realizing what he’s doing until it’s too late. He drags her into the driving seat, puts the car in gear and aims it at the nearby river. Grefé and cinematographer Edmund Gibson here provide a striking point-of-view shot through the windshield as the car hits the water and begins to flood, a nice visual touch which adds impact to the scene (just one of many instances indicating Grefé’s thoughtful use of expressive camerawork throughout the film).

Moving on, Stone arrives in a new town where he meets several people who will become the focus of the narrative. First, a hard-bitten young girl named Tina (Kim Nicholas), then her mother Ann Moy (Jennifer Bishop), and finally Ann’s friend Julia (Ruth Roman); each meets him independently and forms an impression which reflects as much what they want from him as who he really is. Only Tina, grieving the loss of her father and resentful that her mother doesn’t seem to share her pain, senses that there’s something not right with him. The two women are both attracted to him and vulnerable to his phony business deal scam.

Tina’s suspicions are confirmed when she follows Stone – first discovering that her mother is becoming romantically involved, and then more seriously witnessing him committing a brutal murder. His victim this time is a big man named “Karate” Pete (Harold Sakata, Goldfinger’s henchman Oddjob), an old associate of Stone’s who shows up looking to cash in on his money-making schemes. The killing begins with an attempt to hang the big man, and ends with Stone running him down in a car wash.

As Tina runs away, Stone realizes she’s seen all this and threatens to kill her if she tells anyone – a warning which seems unnecessary as neither Ann nor Julia believe her, accusing her instead of being a vicious little liar. But things have become very messy for Stone and he gets increasingly sloppy and dangerous as he tries to squeeze as much money as possible from the two women before fleeing town, leading to a bloody, violent climax which brings the film full circle as another child is forced to kill to protect her mother.

Although there are some inevitable narrative holes (we never really know what Stone’s past relationship with Pete was), Tony Crechales’s script is for the most part tightly constructed with well-drawn characters whose individual flaws play off one another as the threads draw inexorably together around Shatner’s increasingly unhinged performance; his superficial air of self-assurance cracks to reveal the frightened child he’s never really grown beyond who can only deal with stressful situations by striking out violently. For a low-budget exploitation movie shot quickly in a couple of weeks, Impulse displays more psychological nuance than you might expect and Grefé delivers the story with some genuine visual style and attention to performance.

Although the original negative was lost long ago, Grindhouse have done wonders with what their note says is a damaged and faded print. The 4K restoration looks excellent, with very little damage on display and vibrant colours (Shatner’s costumes are almost as egregious as his character’s crimes). For a movie which has remained pretty obscure for decades, this is a welcome example of digital resurrection.

But Impulse is merely the centrepiece of the set. Grindhouse have also included two radically different movies, both quite surprising in light of what is already available on disk from Grefé’s filmography. I’m afraid there’s not a lot to say about The Godmothers (1973), made between Stanley (1972) and Impulse. This strained comedy was written by and stars Mickey Rooney and his friends as cartoonish gangsters prone to malapropisms and pratfalls as they try to avoid being forced to marry the boss’s “fat and ugly” daughter. Apparently Rooney would write new scenes daily and hand them to Grefé on set, with no time to prepare, and he and his friends would improvise, dragging scenes out with painfully unfunny business. It’s a strain to sit through and makes you wish Grindhouse had included one of the early racing movies instead.

Much more interesting is The Devil’s Sisters (1966), Grefé’s fifth feature, made quickly on the heels of Sting of Death and Death Curse of Tartu, and completely unlike those two pulp horrors. In fact, it’s unlike anything else he ever made, closer to the “roughies” being made on the fringes of the business as the hold of the Production Code loosened between the era of nudie-cuties and the rise of mainstream porn. Based on a “true crime” story and shot mostly silent, with almost non-stop voice over explaining what’s going on, it begins with the police arriving in a village where the women insist that the unsympathetic men listen to the story of a badly beaten woman named Teresa (Sharon Saxon).

The story she tells is of a naive village girl who left home for the city, answering an ad for a housekeeper. But she was lured by a gang of sex traffickers run by sisters Carmen (Velia Martinez) and Rita Alvarado (Anita Crystal). Imprisoned, Teresa is raped by the sisters’ henchmen and sold to unsavoury customers. The abuse becomes increasingly brutal and it seems obvious that she won’t be able to survive for long; with help from other imprisoned women, she manages to escape and makes her way to the village where we first encountered her. Complicating her story is the fact that one of the policemen had tried to seduce her back in her home village, eventually attempting to rape her – which is why she left home for the city – and finally got his way by paying the sisters for an opportunity to assault her in their brothel.

Narratively grim and shot in harsh black-and-white, like many movies in its genre The Devil’s Sisters is predicated on the physical and sexual abuse of women, but it also provides a pointed critique of the power imbalance which underlies that abuse, with the forces of “law and order” themselves fully implicated.

This movie was also resurrected from oblivion, though not as successfully as Impulse because the final reel remains lost. Daniel Griffith’s Ballyhoo Pictures restored the existing reels, but the ending – from Teresa’s escape to the fate of the two sisters – had to be sketched in with Grefé addressing us directly along with some storyboard drawings. Not entirely satisfactory, but it’ll have to do as it’s the only way to make the film available. So different from Grefé’s other movies, The Devil’s Sisters throws light on the versatility required from filmmakers working on the fringes, seizing opportunities as they present themselves and adapting to the requirements of the material.

I’ve barely scratched the surface of the set’s extras, which include interviews, Q&As, commentaries, even a three-part five-hour filmmaking seminar given by Grefé. There are three industrial films from later in his career, totalling almost an hour, and an odd assortment labelled “short films”, which includes what appears to be a brief show reel for a proposed feature called The Iceman, written and directed by Grefé, and a twenty-minute digest version of a feature called Underwood (2019) written and directed by John McLoughlin, a ghost story with Grefé cast in a major role. The actual shorts are Thumbs (2019), a brief gag written and directed by Grefé, obviously annoyed by people who can’t tear themselves away from their cell phones, and A Cask of Amontillado (2013) by Jeff Freeman, in which Grefé has a dispute with another filmmaker about the quality of his horror movies and starts to brick the guy up until they finally bond over a mutual dislike of Roger Corman.

This release is an excellent companion to Arrow’s box set, confirming Grefé’s status as an interesting regional filmmaker and an engaging personality, still working into his nineties.

Comments