Recent Asian releases from Eureka

Is it my imagination, or has Eureka come to focus mostly on Asian movies? The company’s older disks in my collection are mostly Hollywood and European classics, but it seems that in the past couple of years Chinese and Japanese films dominate. Or is that just a matter of where my tastes have drifted – I am waiting for their new box set of Andrzej Zulawski’s early films (particularly the restoration of On the Silver Globe), but all my recent acquisitions in both the Eureka and Masters of Cinema lines have been Asian.

Hopping Mad: The Mr. Vampire Sequels

Ricky Lau’s Mr. Vampire (1985), produced by Sammo Hung, was a huge success, building on the horror-comedy genre Sammo had all-but launched single-handedly in Hong Kong with Encounters of the Spooky Kind (1980) and The Dead and the Deadly (dir. Wu Ma, 1982), so it’s not surprising that it spawned a number of sequels. Competing with a flood of imitators, producer Hung and director Lau stretched the basic concept into different variations rather than just trying to repeat their initial success. While they deserve credit for taking a few chances, the results are mixed and, for me, none of the sequels reaches the heights achieved by Mr. Vampire.

In Mr. Vampire II (1986), a team of present-day archaeologists discover a cave in which a family of vampires have been imprisoned and inadvertently set them free. The broad slapstick of the opening scenes sets a tone which discards the horror part of the horror-comedy equation, and when the vampire child is separated from his vampire parents and finds himself taken in by some suburban kids, it becomes obvious that the target audience is, well, kids. Lau does stage some funny scenes with the children and their new silent, hopping friend, but the movie has a light, throwaway quality which points towards a quick attempt to cash in on the previous film’s success.

Despite bringing the story into the present, the original film’s Taoist priest (Lam Ching-Ying) turns up to put a lid on the vampire family (albeit under a different name); he reappears again in Mr. Vampire III (1987) as the action returns to the past. Another Taoist, Mao Ming (Richard Ng) has teamed up with a couple of ghosts, faking hauntings and then charging people for exorcisms (much like Michael J. Fox in Peter Jackson’s The Frighteners [1996]). Having run into some other powerful ghosts, he moves on to the next village where he and his spirit companions get caught up in a fight between Lam’s Master Gau and an evil sorceress. As he joins forces with Master Gau, Mao comes to accept that humans and spirits shouldn’t try to hang out together.

In The Vampire Saga IV (1988), the comedy and horror are almost equally split with the first half of the film dealing with the comic rivalry of a Taoist priest (Anthony Chan) and his neighbour, a Buddhist monk (Wu Ma), who annoy each other with their clashing ceremonies. Each has a protege, the klutzy Chia-Lok (Chin Kat Lok) falling for the newly arrived Ching-Ching (Loretta Lee) who has just moved in with the Buddhist. The leisurely character comedy is interrupted halfway through as a procession carrying a large ceremonial coffin passes by and an aristocratic vampire is inadvertently unleashed. Inevitably, the neighbours have to overcome their personal antagonisms and work together to defeat the monster. Despite the absence of Lam Ching-Ying, this is the best of the sequels, genuinely funny and possessing an impressive menace in Cheung Wing-Cheung’s aristocratic vampire.

For the fourth sequel, Ricky Lau was replaced as director by Lam Ching-Ying, who also returns as the Taoist priest. There are some interesting innovations in Vampire vs Vampire (1989), though it’s unevenly paced and inconsistent in tone. The priest and his two students find themselves in a village with a Christian mission inhabited by a group of nuns. Helping to do some building repairs, they inadvertently release a vampire which has been trapped in a secret room since a priest pinned it down with a cross. This is no hopping vampire, though, but a western aristocrat like Dracula (Frank Juhas). The “vs” part of the title applies to a return of a cute kid vampire like the one in the second film, who helps the priest fight the western intruder.

Although none of the sequels can match the original Mr. Vampire, each is entertaining in its own way and it’s interesting to see the filmmakers play with the genre they created to find new angles. The two-disk set includes multiple commentaries and a couple of brief featurettes on the genre and the rituals used in the films to combat the vampires.

*

Lady Reporter (Mang Hoi & Corey Yuen, 1989)

Cynthia Rothrock, a high-ranking martial artist, was recruited by the Hong Kong film industry in the mid-’80s, making her debut co-starring in Michelle Yeoh’s breakthrough hit Yes, Madam! (Corey Yuen, 1985). Having proved both her action skills and her considerable screen presence, she began a busy and successful career which has lasted four decades – following her debut, she had a spectacular fight with director-star Sammo Hung in Millionaires’ Express the following year, followed by supporting roles in a series of action movies over the next couple of years. Then, in 1989, she became the first western performer to be given the lead in a Hong Kong action movie.

Although Mang Hoi’s Lady Reporter, aka The Blonde Fury (1989), shows signs of a troubled production (it’s rife with continuity problems, including Rothrock’s hairstyle changing from scene to scene and sometimes within scenes, and characters who appear and disappear at random), the narrative more or less hangs together, at least sufficiently to provide an excuse for a series of impressive action sequences in which Rothrock displays a fearless commitment the equal of such stars as Jackie Chan, Yuen Biao and Sammo Hung. She also carries an authority too often denied female performers in Hong Kong movies, which had a tendency at the time to treat them as the butt of sexist jokes.

Rothrock plays FBI agent Cindy, sent to Hong Kong undercover as a reporter to expose newspaper publisher Ronny Dak (filmmaker Ronny Yu enjoying himself as the villain) as a counterfeiter flooding Asia with phony U.S. currency. Local police official Melvin Wong (played by Melvin Wong) knows who she is and warns her not to interfere in Chinese business, but she arrogantly asserts her authority as an American to do whatever is in her country’s interest. The messy story has Cindy staying with her friend Judy (Elizabeth Lee), whose father (Roy Chiao) is a prosecutor also on the trail of the counterfeiters. When he’s kidnapped, Cindy teams up with an undercover cop (Chin Siu-Ho) and gets into a series of bone-crunching fights – a high point is the brutal fight between Cindy and a grim henchman played by an uncredited Muay Thai champion who had no movie experience and was fighting for real – leading to a climax which takes place on a speeding semi. (The scene with the Muay Thai fighter was originally intended to be the climax, but was moved earlier when Corey Yuen stepped in to reshoot some material and provide a bigger ending.)

Other points of interest are the absence of any potential romance between Cindy and the undercover cop – she’s totally focused on her mission – while she has a warm friendship with her friend Judy, making the movie decisively female-centric. Lady Reporter isn’t a particularly good movie – the best action films work well on all levels, supporting the set-pieces with strong stories – but it is an excellent showcase for Rothrock. Like many such performers, she has had a long career which consists mostly of less-than-stellar projects built around her physical skills, while not offering many opportunities to display her abilities as an actress. But here, as in most of her later work in the States, she shows herself to be the equal of many higher-profile martial arts stars.

The disk includes two full-length commentaries, plus a select-scene commentary from Rothrock, as well as new interviews with Rothrock and director Mang Hoi.

*

Revenge (Tadashi Imai, 1964)

Bushido, the samurai code, cast a centuries-long shadow over Japanese society which culminated in the militaristic horrors of the early 20th Century and Japanese domination of Asia with brutal colonial occupations of Korea and Manchuria, finally brought to an end by World War Two. The code applied to the samurai class which comprised the retainers of Japan’s rulers during the two-and-a-half centuries of the Tokugawa Shogunate and on through the restoration of the Emperor in the mid-19th Century. Its defining characteristic was absolute obedience and a willingness to kill and die without hesitation; paradoxically, the relative stability of the oppressive Shogunate imposed a general peace on Japan which limited opportunities for martial glory. The samurai were thus consumed with issues of status defined by ritual and minute gradations of class.

As the Western served to create a lasting self-image for America of rugged individualism and Manifest Destiny, the samurai movie, or chanbara, has been important in creating a particular image of Japan’s past – and like the Western, the samurai film offers a range of positions from which to view history, from a validation of selfless heroism to a cutting critique of dangerous cultural tendencies. A common theme in the genre is the cycle of revenge which the code encouraged, with real (or perceived) wrongs answered with violence, which triggers more violence in return. With identity depending entirely on social position, any slight, no matter how small, could cause a sense of humiliation which in turn demanded restitution, often through violence. Death was more desirable than dishonour and transgressions could be resolved only through ritual combat or suicide.

If stories of samurai honour sometimes seem to imply that this class formed the whole of Japanese society, other narratives focus on villagers, rural peasants, the dispossessed, and the crushing effects of the rigid social order on the larger population – these range from movies like Kenji Mizoguchi’s Ugetsu Monogatari (1953), Akira Kurosawa’s The Hidden Fortress (1958) and Kaneto Shindo’s Onibaba (1964), which depict peasants who seek wealth and/or martial glory, to the more lowly Zatoichi movies (1962-73) which focus on the hardships faced by ordinary people living on the lower levels of the oppressive class system. Another common theme is the ronin, samurai who have lost their masters and yet cling to their code even though they have no fixed place in society, reduced to selling their skills where they can, either clinging to a sense of honour or embracing their identity as pariahs, like the masterless samurai played by Toshiro Mifune in Yojimbo (1961) and Sanjuro (1962).

By the ’60s, as Japanese cinema addressed the nation’s problematic history during the post-war recovery, filmmakers explored the darker side of Bushido, the senselessness of mindless obedience and pointless violence. Kihachi Okamoto’s The Sword of Doom (1966) depicts its samurai protagonist as a pathological killer, while Masaki Kobayashi’s Harakiri (1962) explores the senselessly destructive consequences of the rituals which gave rigid structure to the samurai class. A new release in this genre from Eureka’s Masters of Cinema line has introduced me to a film, a director and a star previously unknown to me.

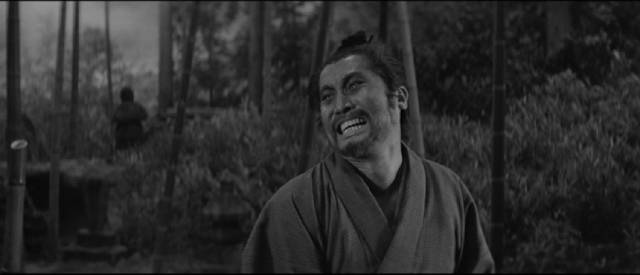

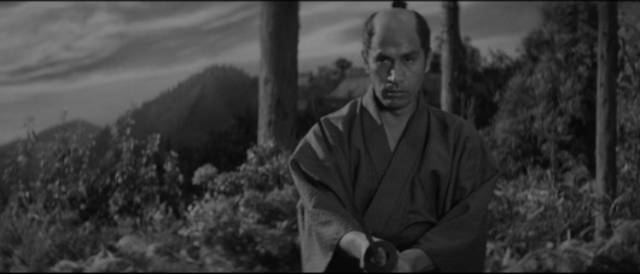

Tadashi Imai’s Revenge (Adauchi, 1964) was an anomalous production from Toei, better known as a prolific purveyor of B-movies. In fact it opens with a text card before the studio logo bluntly stating that it was made as their “entry into the 1964 national arts festival”, a deliberate attempt to claim some prestige. This bleak exploration of madness and death is the equal of similar movies being made at the time by bigger companies like Toho and Shochiku; this is partly due to a tightly-constructed script by frequent Kurosawa collaborator Shinobu Hashimoto, but ultimately rests on the direction of Imai, the stunning widescreen black-and-white cinematography of Shunichirô Nakao, and particularly the intense central performance of Kinnosuke Nakamura as a low–status samurai named Shinpachi Ezaki, a man trapped by his social position and driven mad by his escalating rage.

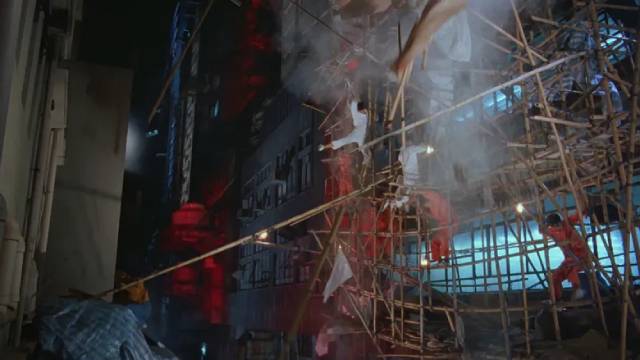

The narrative is framed by preparations for a formal duel which will provide a spectacle for the clan and the local peasants who see it as a festive break from the daily grind. A large compound is erected on an open hillside, the bamboo fence constructed according to very detailed specifications laid down by tradition. As this work continues through the morning, with the dual scheduled for noon, the film loops back with a series of flashbacks to the events which have led to this day, exposing the absurdity of the code which has trapped everyone involved in a pointless process which reveals how corrupt the code governing the clan actually is.

It all starts with a minor insult. Shinpachi is an armourer who is laying out spears when the heir of the clan passes and complains that the spears are not clean. Shinpachi stands up for himself, which infuriates the heir, who sends him a challenge to a duel even though this violates clan rules (duels are formal legal events which require investigation and approval), but Shinpachi feels compelled to accept and ends up killing the heir. Because the event wasn’t sanctioned, the clan authorities face a dilemma – it wasn’t just Shinpachi who broke the rules, but also the heir. It’s decided that both participants must be declared mad in order not to cause further problems and Shinpachi is exiled to a monastery, where he chafes at the injustice since it was, after all, a fair fight.

The heir’s brother Okuno (Tetsurô Tanba) becomes the new heir, but isn’t happy that Shinpachi wasn’t properly punished. He feels that the “madman” should be put down like a troublesome animal and decides to go to the monastery and kill him. Warned ahead of time, Shinpachi prepares an ambush and in a brief fight kills Okuno. This compounds the problem for the clan; if they had handled the original incident differently Okuno would still be alive and now they have to find a way to restore order. So the remaining younger son and new heir must issue a formal challenge to a duel, which must be approved by the authorities.

Although in both cases Shinpachi was essentially operating in self-defence against his superiors, his lowly position by definition puts him in the wrong and everyone views him as a dangerous murderer. Order can only be restored by a formal contest in which he must die. His own brother argues with him to passively allow the young heir to kill him without an actual fight; while this infuriates him, he realizes that he has little choice – even if he flees, he’ll be a pariah, hunted down and executed as a criminal. So, despite seething at the injustice, he enters the duel enclosure prepared to submit.

But with only the young heir left, a boy who’s no match for the man who killed his warrior brothers, the authorities have prepared an ambush, further violating the rules of the code. This won’t be a fair fight, but an execution, an act of butchery. As the duel begins, a half dozen armoured retainers rush from cover to stand between Shinpachi and the terrified heir; though Shinpachi pleads with the authorities to adhere to the rules, they allow things to proceed, triggering Shinpachi’s fury. He fights like the madman people believe him to be, killing most of the retainers and then turning his anger on the officials themselves. But outnumbered, he eventually falls and the heir is called on to give the final blow in order to complete the “duel”, but he’s unable to act – it’s all a bloody, futile mess which exposes the clan as duplicitous and its governing code to be a complete sham.

Revenge is brutal and intense, and yet there are actually only two sequences of on-screen violence – the brief fight with Okuno and the protracted climactic “duel”. Much of the film consists of conversations about what has happened and what should be done about it. Hashimoto’s script makes all this compelling, and Imai gives it a sense of doom-laden inevitability, while Nakamura’s performance is filled with barely contained fury which at times becomes indistinguishable from outright madness. All the violence and horror arises directly from the samurai code which is exposed as untenable; supposedly providing a framework for stability and purpose, it actually produces chaos.

The Blu-ray looks quite stunning – I can’t get enough of that widescreen black-and-white – and two featurettes with Tony Rayns (22:05) and Jasper Sharp (15:57) provide useful context with information about the genre as well as the careers of Imai and Nakamura.

*

Samurai Reincarnation (Kinji Fukasaku, 1981)

My first conscious encounter with the work of Kinji Fukasaku wasn’t auspicious. I saw Message from Space (1978) on its theatrical release, just another silly Star Wars knock-off and nowhere near as entertaining as Jimmy T. Murakami’s Battle Beyond the Stars (1980), which came out a couple of years later. Message also made me aware of the earlier release of The Green Slime (1968), a movie with a very bad reputation, so Fukasaku seemed to be of little interest. (I’d also seen Tora! Tora! Tora! [1970] on its theatrical release, but his name hadn’t registered at the time, no doubt a result of cultural prejudice – that was a “Richard Fleischer movie”.)

Then, two decades later, I got my hands on a DVD of Battle Royale (1999) and I was blown away. How on Earth had this movie, with its fierce energy, been made by a seventy-year-old filmmaker? I immediately went in search of other films, quickly discovering a remarkable range of work in multiple genres – crime noir, yakuza stories, sensitive dramas like The Geisha House (1998, made just before Battle Royale for a remarkable contrast), strange unclassifiable films like Black Rose Mansion (1969), a perverse slice of erotic noir starring female impersonator Akihiro Miwa as a singer who’s the object of several men’s lust. He had also made a number of samurai films with a brutally harsh view of the history underlying the genre – it was as I accumulated Fukasaku’s movies on disk that I realized I’d actually seen one of these in a theatre a couple of decades earlier; Shogun’s Samurai (1978) was the first movie I saw when I went to live in Hong Kong for a while in 1980-81, but again the director hadn’t registered at the time. That bleak and violent refutation of samurai nobility had been made immediately before Message from Space, as another indication of his range. As I discovered more of his work, he quickly became one of my favourite Japanese directors.

Given the harsh view of modern Japan shown in his yakuza movies, it’s not surprising that Fukasaku had no romantic illusions about the past. His samurai movies are blunt and brutal, their stories stripped of any aesthetic elegance which might distract from their unblinking attention to the social, political and philosophical underpinnings of feudal Japan. His Sword of Vengeance (1978) remains my favourite version of the famous story of the 47 ronin, usually presented as a tragedy rooted in the idea of honour and sacrifice, but in Fukasaku’s hands an unflinching depiction of senseless violence and wasted lives.

But alongside his revisionist historical films, Fukasaku also made a couple of movies which combined the chanbara with supernatural elements, adding overt fantasy-horror tropes to the historical horrors. In Legend of the Eight Samurai (1987), a princess is aided by the eight samurai against a clan of ghost warriors who want her skin to resurrect their dead lord. Samurai Reincarnation (1981), however, roots its horror in a historical reality. The Shogunate managed to retain its power for so long in part because it sealed Japan off from outside influences, one of which was Christianity which had gained a foothold in the 16th Century. When Christians aligned themselves with a peasant uprising in the mid-17th Century, the Shogunate banned them outright as a threat to Japan. (This repression was also the basis for Masahiro Shinoda’s Silence [1971].)

The torture and killing of missionaries culminated in the massacre of an estimated thirty-seven-thousand Christians in 1638 in the wake of the peasant rebellion. This is where Fukasaku’s film begins, with the forces of the Shogunate celebrating their victory beside a plain piled high with slaughtered Christians, some of whom are hung from crosses. Among the crucified is Shiro Amakusa (Kenji Sawada), leader of the rebellion, who by force of will returns from death having made a pact with the forces of darkness because his god has failed him. Summoning occult powers, he lays waste to the victors and then proceeds to locate and resurrect a number of historical figures who have unfinished business in the world, forming a small personal company with which he sets out to destroy the Shogunate.

Given the lengthy intro – a series of chapters dealing with each of the four figures Amakusa revives – and the massacre which motivates his desire for revenge, viewer sympathy tends to lie with him, but the film’s hero is actually Jubei Yagyu (Sonny Chiba), son of one of the Shogun’s master swordsmen. He is tasked with stopping the spirit warriors before they unleash Hell on Earth, a mission complicated by the fact that one of Amakusa’s warriors is Jubei’s own father (played by Lone Wolf and Cub’s Tomisaburô Wakayama himself).

With its striking cinematography by Kiyoshi Hasegawa, rousing score by Hozan Yamamoto, excellent cast (which also includes Ken Ogata as Musashi Miyamoto, and Hiroyuki Sanada, who later starred in Yôji Yamada’s elegiac The Twilight Samurai [2002]), and its breathless pace, Samurai Reincarnation is Fukasaku at the top of his form, transforming history into furious entertainment with a fiery climax which apparently was extremely dangerous for Chiba and Sawada, who fight their final duel amid a raging fire as the Shogun’s palace burns.

The Masters of Cinema disk presents the film in a colourful 2K restoration, displaying a lot of detail even in the many dark scenes. There’s a commentary from Tom Mes and a twenty-five minute discursive interview with Kenta Fukasaku, the director’s son, who discusses the film, reminisces about his father and talks about hanging out with Sonny China when he was young. This release is a nice beginning; hopefully Eureka will put out more of Fukasaku’s work in new restorations.

Comments

Thanks for another in-depth review! I’m a big fan of Japanese classic cinema and have most of the movies you referenced in my collection.

I will now have to track down a copy of Revenge. The movie sounds great. It reminds me a little of a couple of other samurai movies that dealt with betrayal and revenge against the system…. Samurai Rebellion and my personal favorite… Sword of the Beast. Both of these movies are in Criterion’s Rebel Samurai: Sixties Swordplay Classics.

I guess the tv series The Lone Wolf and Cub is also along these lines. I have that Zaitoichi box set. Great movies. They all have a similar theme but don’t get boring for some reason….

Perhaps it’s due to a problematic sense of exoticism, but overall I enjoy samurai movies more than westerns. Particularly in the ’60s and after, they seem to have a more acutely critical view of Japanese history than the western, which although it did finally begin to call into question the American myth of “the spread of civilization” largely remained embedded in that myth, with movies like The Wild Bunch more a lament for the loss of American greatness than a dissection of what that “greatness” truly consisted of – few have been able to escape the American obsession with the individual who forges his own destiny. Most of the samurai films I’ve seen present this warrior class as deeply embedded in the larger society, with troubling consequences for the larger population. But all that’s said from an outsider perspective whose knowledge of Japanese history and culture is largely derived from the movies themselves, so it may be a lot of hooey propping up my liking of these movies!