Summer viewing, 2023: Vinegar Syndrome

It’s been a crazy summer, both in a general sense – erratic, frequently violent weather – and personally, with some dispiriting health issues. But I just can’t stop watching movies, so as always I’m way behind in my comments. Once again, then, some brief (inadequate) notes on recent disks.

I probably won’t be renewing my Vinegar Syndrome subscription next year. Although there are some advantages – the free shipping and discounts on non-subscription items – it’s fairly expensive and it locks me into a not inconsiderable number of releases which I wouldn’t otherwise be interested in. They also increasingly lavish 4K restorations and dual-format status on movies which really don’t seem to warrant the effort.

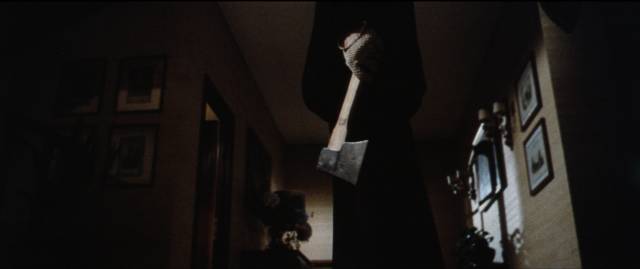

Night Screams (Allen Plone, 1987)

These include a couple of minor (not particularly good) ’80s regional slasher movies. Allen Plone’s made-in-Wichita Night Screams (1987) piles on layers of indirection and a variety of murder-methods but without managing to be more than mildly interesting. A high-school football star with psychological issues throws a party while his parents are away. Not only has he run out of the meds which keep him from suffering fits of rage, a pair of escaped psychos are hiding out in the basement. As the evening progresses, his guests get knocked off one by one – electrocuted in a hot tub, fried on a grill, hacked with an axe, etc. – seemingly by the psychos, though this is upended by a late reveal, the truth finally obscured by the kid’s medical condition. The three-disk set includes the original cut, deemed too short by the distributor, and the theatrical version which includes additional nudity and sequences culled from Herb Freed’s 1981 slasher Graduation Day to pad the running time. There’s a commentary, plus a feature-length making-of.

Terror at Tenkiller (Ken Meyer, 1986)

Despite its weaknesses, Night Screams does resemble a standard slasher. Terror at Tenkiller (1986) is something else. Shot in Oklahoma, it was the sole effort of co-writer/director Ken Meyer, and it seems uncertain what it wants to be. Slasher elements are grafted onto a seemingly serious drama about two women friends, one of whom is trying to help the other get out of an abusive relationship by taking her away for the summer to a cabin at Tenkiller Lake where they get jobs at the local diner. There’s no mystery about the serial killer in the neighbourhood because we see him in action in the opening sequence; he’s the guy who works at the boat dock and the abused woman begins a tentative relationship with him – while he starts killing anyone who might get between them. No mystery, and little suspense. The two-disk dual-format set includes a commentary and making-of doc, but the most interesting extra is a half-hour student film by Meyer’s son Kevin and Jeff Burr; Divided We Fall (1982) is an ambitious Civil War story about a Southern farmboy, disgusted with his own family’s involvement in slavery, who runs away and joins the Union army, eventually coming face to face with his brother on the battlefield. This film also gets a commentary, making-of and behind-the-scenes featurette.

A Blade in the Dark (Lamberto Bava, 1983)

Continuing in the slasher vein, Lamberto Bava’s second solo feature A Blade in the Dark (1983) displays the roots of the American genre in the Italian giallo. Stylistically, this is one of Lamberto’s most accomplished movies, clearly showing the influence of Dario Argento, on whose Tenebre (1982) Bava had just served as assistant director. It’s also, like Demons (1985), an overtly self-referential work; the protagonist is a musician hired to score a horror film. He’s set up in a modernist villa which he doesn’t know is connected to the real-life story the film is based on and finds himself interrupted by unexpected visitors who mysteriously disappear – because someone is lurking around and killing them. There are issues of gender confusion rooted in the film-within-the-film’s backstory, emphasized by the unusual detail that that movie’s writer-director is a woman (very atypical in Italian genre cinema).

Vinegar Syndrome’s elaborate four-disk dual-format edition includes both the theatrical version and the longer cut originally intended for television – this was set aside when the graphic violence was deemed too extreme for TV. Each version gets its own disk in both formats, with the longer cut given two commentaries. In addition there are multiple interview featurettes and a visual essay on Lamberto’s horror movies by Samm Deighan. Also included is Severin’s documentary from a few years back, All the Colors of Giallo (2019).

5 Women for the Killer (Stelvio Massi, 1974)

Stelvio Massi is best-known for his poliziotteschi and action movies, but early in his directing career he contributed a giallo which looked ahead to the genre’s sleazier decline in the later ’70s and ’80s. 5 Women for the Killer (1974) mixes police procedural with giallo elements. A reporter arrives back in Italy to learn not only that his wife has died in childbirth but that he himself is actually sterile, so the baby couldn’t be his. Very soon a gloved killer is murdering (in fairly graphic scenes) other pregnant women who have been attending the same clinic as his wife. Suspicion falls on him because of his recent experience. A minor, but fairly effective giallo, Massi’s little-known film gets its first real international exposure here on Blu-ray in Vinegar Syndrome’s uncut 4K restoration, with commentary and a handful of interview featurettes.

Delirium (Renato Polselli, 1972)

As sleazy in its own way is Renato Polselli’s Delirium (1972), with Mickey Hargitay as impotent Dr. Lyutak who has uncontrollable urges to murder women when sexually aroused. He’s revealed as a killer in the film’s opening sequence, but then puzzlingly other murders occur when he couldn’t possibly be involved, particularly since as a psychologist he’s helping the police in their investigations. While the final revelation that clarifies and makes sense of what’s been happening may not be a big surprise, Polselli handles it well. Once again VS give this minor movie a 4K restoration, with commentary and interview featurettes, adding to their catalogue of sleazy Italian exploitation.

Gorgo (Eugène Lourié, 1961)

Inhabiting an entirely different cinematic universe is Eugène Lourié’s Gorgo (1961). Lourié, a renowned production designer and art director, was a minor director of occasional movies and television episodes who somewhat specialized in giant monster movies – three of his four theatrical features involve the reawakening of giant dinosaurs which end up trashing a city. The first was Ray Harryhausen’s The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953), which ends up in New York; followed by The Giant Behemoth (1959), with the uncredited involvement of Willis O’Brien, and finally Gorgo (1961), the latter two both seeing London laid waste.

The best of the three is Gorgo, which eschews stop-motion for a man-in-a-suit monster, which aligns it more with Japanese kaiju than ’50s U.S. monsters. Like most of these movies, it has a fairly rudimentary narrative which serves as an excuse for the visual effects – which in this case are pretty impressive. Shot in Technicolor by Freddie Young the year before his work on Lawrence of Arabia (1972), the first of three collaborations with David Lean which won him Oscars, the look of the film belies its relatively small budget, and the climactic destruction is impressive – the scale and lighting of the miniature sets, and the compositing of live action and miniatures, is as good as anything in Toho’s kaiju movies.

Gorgo was first released on Blu-ray by VCI in 2013 in a decent edition, but VS’s new 4K restoration from the original 35mm negative seems more vibrant and colourful, though the improvement also emphasizes the movie’s technical flaws – the variable quality of stock footage inserts and occasionally shaky bluescreen effects. But the film still has considerable charm. The dual-format release has a commentary and featurette with Stephen R. Bissette, a couple of archival featurettes, and a charming short from 2009 called Waiting for Gorgo; written by M.J. Simpson and directed by Benjamin Craig, this has a young civil servant delving deep into a ministry basement to find a pair of aging men who spend their days waiting to activate a response to the reappearance of Gorgo, not realizing that their lives and careers have been wasted on a movie fantasy. Witty dialogue (with an obvious nod to Samuel Beckett) and fine performances make this a surprisingly effective tribute to England’s answer to Godzilla.

The Boogey Man (Ulli Lommel, 1980)

Ulli Lommel began as an actor in the early ’60s, including roles for both Russ Meyer and Rainer Werner Fassbinder. While he’s continued to appear in movies and on television up to the present, he began writing and directing in the early ’70s. He’s been prolific, and though I’ve seen very little of his work, I venture to say that his best film remains his third feature, a collaboration with Fassbinder called The Tenderness of Wolves (1973), a variation on the story of real-life serial killer Fritz Haarman. At the end of the ’70s, Lommel went to the States, where he became involved with Andy Warhol, under whose auspices he made a couple of movies (Cocaine Cowboys [1979] and Blank Generation [1980]). But he quickly moved away from that milieu to become a prolific maker of exploitation movies, with a long-running interest in serial killers and horror.

This career really began with The Boogey Man (1980), made between the two Warhol-connected movies. Co-written with his wife Susanna Love, who also stars, this might be considered some kind of deconstruction of popular genres, exploitation as art-film experiment – or, less charitably, a mess which grabs numerous familiar elements and throws them together haphazardly. Part slasher, part supernatural horror, part drama about the lingering effects of childhood trauma, it begins with a young boy murdering his mother’s abusive boyfriend in front of his sister, the act reflected in a large mirror. Years later, the boy lives with his sister and her husband, never having spoken again after that traumatic night, about which the sister still has nightmares.

During a visit to the house where it happened, the sister sees the abusive man in the same mirror on the wall and smashes it, unleashing a malevolent force which begins to kill people in the area, starting with the current residents of the house and spreading out as fragments of the broken mirror turn up in various places. While Lommel can’t seem to tell a coherent story, the movie does generate an atmosphere of supernatural menace and its seeming refusal to adhere to strict genre expectations makes it interesting in its own idiosyncratic way, even if it’s never entirely satisfying. As a knowing nod to the genre traditions it refuses to adhere to, Lommel managed to cast an aging John Carradine in the small role of a psychologist the sister consults about her bad dreams.

Previously released on Blu-ray in 2015 by 88 Films, The Boogey Man gets a 4K restoration and dual-format release from Vinegar Syndrome, looking as good as it can. There are two commentaries, including one with the ubiquitous Kat Ellinger, plus a handful of new cast and crew interviews and an archival interview with Lommel.

Undefeatable (Godfrey Ho, 1993)

Godfrey Ho’s Undefeatable (1993) is yet another mediocre movie in which Cynthia Rothrock gets to display her fighting abilities and not-inconsiderable screen presence. Like many of her peers, her career has consisted largely of vehicles which exploit her talents without offering her material worthy of them. Which is not to say Undefeatable is without interest as an action-driven exploitation movie. Cynthia plays Kristi, a woman who accepts her own limited prospects as she engages in illegal street fights to earn money to put her sister through college.

Meanwhile, martial arts champ Stingray (Don Niam) brings the violence home from the ring, becoming increasingly abusive towards his wife Anna (Emille Davazac). When she finally gets up the nerve to leave him, he goes over the edge – every woman who vaguely resembles her triggers his deranged anger; he kidnaps, abuses and kills them, finally taking their eyes, which he keeps in jars. When he targets Kristi’s sister, she joins forces with cop Nick DiMarco (John Miller) to track down the killer, leading to an extremely brutal climactic fight. Like many of Rothrock’s movies, this doesn’t offer the kind of balletic formalism which many traditional Asian martial arts movies display; the fights are bone-crunchingly brutal and she holds her own against seemingly physically more powerful opponents, making you feel both gratified and relieved when she manages to get the best of them.

The three-disk dual-format set includes the original cut plus the radically different Hong Kong cut which adds a whole second plot about triad gangs. There’s a Rothrock interview and commentary, other cast and crew interviews and a couple of visual essays about Rothrock’s career and the two versions.

*

In addition to these recent releases, I also watched several older catalogue titles.

Jack Frost (Michael Cooney, 1996)

Michael Cooney’s Jack Frost (1996) has the titular serial killer’s prison transport crashing into a tanker truck on an icy road on the way to his execution. The truck was carrying an experimental fluid which mixes Jack’s DNA with a snowbank to resurrect him as a wisecracking, murderous snowman who heads for the town of Snomanton, whose sheriff was the one who captured Jack and started him on his way to the death penalty. The deadly snowman uses a bunch of winter- and Christmas-themed methods to knock off the townspeople until the sheriff figures out what’s going on and finds a way to defeat him. Like many horror-comedies, Jack Frost leans more towards dark humour than actual scares and Jack follows in the footsteps of the likes of Freddy Krueger and Chucky by spicing up his kills with puns and smart-aleck remarks.

Last Gasp (Scott McGinnis, 1995)

Scott McGinnis’ Last Gasp (1995) has Robert Patrick as ruthless businessman Leslie Chase, who’s developing a hotel in a remote area of Mexico. A local tribe resists by ritually killing an occasional construction worker, so Chase leans on the local authorities to wipe out the tribe. They manage to leave one alive, who comes for Chase; in an up-close fight, he manages to kill the man, but as he dies the tribesman breathes his last breath into Chase, who becomes possessed. Several years later, now doing a project back in the States, every few weeks Chase is taken over by the native spirit and has to perform a ritual sacrifice. The wife of one of his victims (Joanna Pacula) tries to expose Chase as a serial killer, but the police dismiss her as hysterical and protect the wealthy man; so she has to take things into her own hands, with inevitable “ironic” consequences. Strangely, Chase ends up seeming a tragic victim himself of ancient tribal magic … making the movie obviously, if not intentionally, pretty racist.

The Caller (Arthur Allan Seidelman, 1987)

Arthur Allan Seidelman’s The Caller (1987) interested me for a couple of reasons – it stars Malcolm McDowell and it was written by Michael Sloan, whose work I’d found interesting in Indicator’s Pemini Organisation set. It’s an odd, unsatisfying movie which seems to be going in a particular direction until it takes an abrupt turn towards the end into a completely different genre. With only two characters, director Seidelman has to work hard to maintain interest – much like the Pemini films Hunted (1972) and Moments (1974). The Girl (Madolyn Smith) lives alone in a remote cabin; one evening a stranger appears at her door, claiming to have been stranded when his car broke down nearby. The Caller (McDowell) seems vaguely threatening, imposing himself on her although she’d obviously like him to leave. Although things are kept vague, I began to suspect that he’s a cop and his probing conversation is designed to get her to expose herself, perhaps for having killed her missing husband. The cat-and-mouse exchanges become a bit repetitive and the continuing vagueness is frustrating … and then it shoots off in a completely unforeseen direction into apocalyptic science fiction, which however remains somewhat vague. It leaves the impression that it probably needed another draft of the script, but the two actors do manage to hold your attention.

Comments