Fall 2023 viewing, part one

It may be time for an intervention. I’ve recently been spending an inordinate amount on new Blu-rays – quite a few special, limited editions which are very expensive – with the influx far outstripping the time available to watch them all. In just the past couple of weeks (as I write), I’ve received large packages from Vinegar Syndrome, Severin, Indicator, Unobstructed View, Classicflix and Second Sight, totalling more than forty releases, including several box sets, plus a few individual items from eBay sellers and Eureka. On top of which, I also took a trip to the store where I trade movies in for credit (two shopping bags full), which netted me $200+ worth of new and used Blu-rays, including a couple of new releases from Radiance (on whose web store I’d already placed a pre-order for October releases). As much as I want to cut back, I’m addicted to the dopamine rush that comes when a package is delivered – it’s like a kid getting Christmas several times a week!

Here’s a run-down of recent acquisitions…

*

Eureka

I’ve already written about new Asian cinema releases from Eureka/Masters of Cinema, but it was only in mid-August that they finally shipped the last remaining item from a February 24th pre-order – a four-disk set of films by Andrzej Zulawski, which includes his first two features (The Third Part of the Night [1971] and The Devil [1972]) and his unfinished masterpiece On the Silver Globe (1988), which had been shut down by Polish film authorities in 1978 before the completion of photography, with the existing elements ordered destroyed. They nonetheless survived and Zulawski pieced together a version years later, filling the gaps with readings from the script and seemingly random footage. Even in this crippled form, it’s a remarkable movie – but I haven’t got around to watching Eureka’s restoration yet, nor an entire disk of extras.

*

Arrow from Unobstructed View

For inexplicable reasons, it’s usually cheaper to order Arrow releases directly from England, but occasionally Unobstructed View has a sale that offers comparable prices without the risk of being hit with customs charges. In late July, I took the opportunity to order three new releases (plus a discount copy of Bruno Dumont’s Coincoin and the Extra-Humans [2018] to reach the free shipping threshold). Although I haven’t yet watched Coincoin or John Mackenzie’s second feature, Unman, Wittering and Zigo (1971), I did watch the two box sets included.

Blood Money is the second of Arrow’s sets of four lesser-known spaghetti westerns. (The third volume is due in early December and of course I already have a copy ordered!) If none of the films included reach the heights of those in the first set, it’s still a strong collection rife with moral ambiguities, characters whose motives constantly shift according to circumstance, and of course lots of violence. The only director whose work I’m somewhat familiar with is Giuliano Carnimeo, who directed four of the Sartana movies, plus The Case of The Bloody Iris (1972) and Exterminators of the Year 3000 (1983). Ironically, the film in this set attributed to him, Find a Place to Die (1968), was reputedly directed by producer Hugo Fregonese – this seems quite likely as it’s the closest to a traditional American western in style, something emphasized by the casting of Jeffrey Hunter as the lead.

I know the name Romolo Guerrieri, mostly because he was Enzo G. Castellari’s uncle and directed the Carroll Baker erotic thriller The Sweet Body of Deborah (1968), which I haven’t seen. $10,000 Blood Money (1967) has Gianni Garko as a bounty hunter modelled on Django, who gets involved with a bandit with tragic results. The bandit is played by Claudio Camaso, who looks very much like his older brother Gian Maria Volonte. Camaso also turns up as Garko’s bad guy brother in Giovanni Fago’s Vengeance is Mine (1967), in which sibling rivalry destroys everyone’s life.

The most interesting film in the set is Cesare Canevari’s Matalo! (Kill Him) (1970), which comes close to being an experimental deconstruction of the genre. Canevari pushes things to extremes with almost abstract camerawork and editing, further disrupting what might be conventional narrative elements with Mario Magliardi’s anachronistic experimental score using heavy electric guitar and electronic effects which blend into a non-naturalistic soundscape. Like Antonio Margheriti’s And God Said to Cain in the first set, Canevari’s film shows how flexible the genre is by pushing the boundaries in unexpected directions.

Teruo Ishii was a master of extreme Japanese genre cinema, notable for his period films, with their emphasis on sex and torture, and yakuza and prison movies. Shin’ichi “Sonny” Chiba was already a black belt in karate when Toei discovered him in 1960, launching a long career in which he played tough guys proficient in martial arts. They teamed up for several movies in the early ’70s, including The Executioner and The Executioner 2: Karate Inferno (both 1974). In the first movie’s opening section, Koga is the young heir to a ninja family, trained with unrelenting ferocity by his grandfather. Years later, now played by Chiba, Koga is one of several men recruited by a police official who has given up on legal methods to bring down a gang of drug dealers: his off-the-books team is to use any method available, essentially becoming hired assassins. The action and fight scenes don’t have the elegance of traditional Chinese martial arts movies; they’re harsh and brutal. There’s less action in the sequel, in which the team is brought together again to thwart a gang of international jewel thieves. Here, Ishii piles on a lot of strained comedy and the change makes the movie much less satisfying.

*

Vinegar Syndrome

It’s no surprise that in terms of sheer volume, Vinegar Syndrome and their partner labels once again dominate my recent movie-viewing. Every month, as a subscriber, I get a big box from them.

Killer Condom (1996) by Martin Walz was a surprise. Its association with Troma, which distributed it in the States, led me to expect something merely cheap and tasteless, rather than a polished German production, shot on location in New York and in studios in Germany, with an unexpectedly progressive attitude to gender-non-comforming sexuality. The grossly funny physical effects (the malevolent, sentient condoms which are biting off the dicks of prostitutes’ clients around Times Square) were created by Jörg Buttgereit (in an interview on the disk, he says his budget for the effects was more than the cost of all his own movies). It’s funny, oddly sweet, and inventively gross.

There’s a lot less art in the four features included in the Cardona Collection 2, though after the three adventure movies with international casts showcased in the first set devoted to prolific Mexican filmmaker Rene Cardona Jr, this new release shows a wider range in subject matter and tone, from the spoof of spy movies S.O.S. Consipracion Bikini (1967) to Under Siege (1980), an exercise in non-stop action which begins with the coordinated robbery of several casinos and follows the chaotic and increasingly violent attempts of the gang members to escape the police who are relentlessly closing in. La casa que arde de noche (1986) is set in a Tijuana brothel (improbably monumental), with an ambitious stripper scheming her way up to take over the business, while Beaks: The Movie (1987) is an absurdly entertaining attempt to update Hitchcock’s masterpiece on a global scale, with a young local TV news reporter somehow having the budget to travel from country to country, through South America and Europe, as she tracks a rising environmental catastrophe involving birds turning against the human race.

There’s even less art in Amazon Jail 1 (Oswaldo de Oliveira, 1982) & 2 (Conrado Sanchez, 1987), a pair of seedy Brazilian women-in-prison movies, the first with a gang kidnapping white women to sell into sexual slavery, the second with a gang kidnapping indigenous women to sell into sexual slavery. Rebelling against abuse and degradation, the prisoners attempt to escape and have to fight their way through hostile jungle pursued by their captors. These are similar to the many made-in-the Philippines WIP movies of the ’70s, though less polished than the work of people like Jack Hill.

Partner Releases

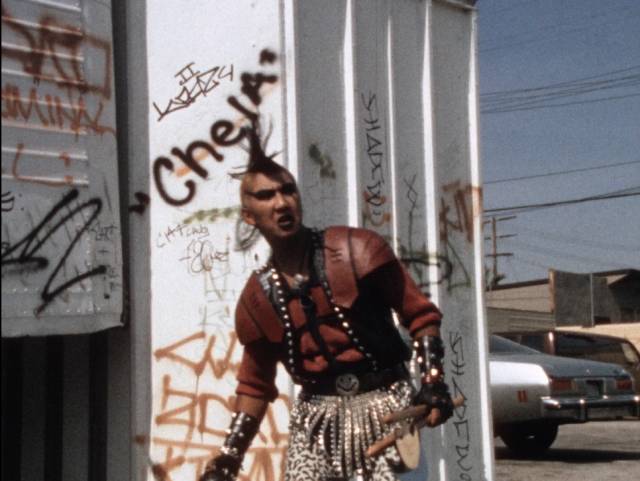

Armand Gazarian’s Game of Survival (1989) – or is that Games of Survival? – is a cheap, derivative sci-fi action movie shot on super-8 which draws on all the equally derivative post-Mad Max, post-apocalypse movies of the ’80s, with a nod to Star Trek‘s 1967 “Arena” episode. A powerful but bored galactic master gathers together a group of the worst criminals on multiple worlds and sends them to contemporary L.A. to fight for a magic ball, with only two stipulations – there’s a time limit and there can only be one survivor. Threadbare but lively within its technical and budgetary constraints, the movie is most amusing with the deadpan reactions of Angelinos as the contestants wander around in their sci-fi costumes carrying an odd array of weapons (as random as those given the students in Kinji Fukasaku’s Battle Royale [1999]).

Thirty-plus years after Gazanian shot his movie with the simplest technology then available, a lot has changed and a limited budget no longer restricts a filmmaker so severely – digital technology is inexpensive, but infinitely more versatile than narrow-gauge film. Thus the proliferation of found-footage movies which foreground the means of their own making. In Robbie Banfitch’s The Outwaters (2022), a filmmaker and three friends head out into the desert to shoot images for a music video. As in so many found-footage horror movies, an inordinate amount of time is spent on mundane activities (including the irritation of the characters about having the camera pointed at them all the time), with a slow accumulation of disturbing touches which are barely noted at first. Some odd noises in the desert, anomalous weather events, glimpses of an unresponsive figure in the distance. And then, the four friends come under attack at night by unknown forces – sounds like thunder, glimpses of snaky creatures slithering across sand, teeth, blood, screams. Banfitch is audacious, building much of his horror through sound design because he limits the visuals to what can be glimpsed in the beam of a small flashlight, leaving most of the frame pitch dark. As with so many found-footage movies, we never get a clear look at the menace, nor any explanation of what it is. I rather admired the extremity of Banfitch’s technique, while ultimately feeling the all-too-familiar frustration this genre produces. I imagine the movie might have been more effective seen on a big screen with an audience because it does have an undeniable visceral impact, one inevitably diminished by home viewing.

The desert also figures in a pair of Australian features from the late 1980s. Shame (1988) is the sole theatrical feature of TV director Steve Jodrell, a contribution to the toxic Outback genre which goes back at least to Ted Kotcheff’s Wake in Fright (1971). Big city lawyer Asta Cadell (Deborra-Lee Furness) is taking a break by riding her motorcycle across the country when she breaks down in a small town; while she waits for parts to fix the bike, she becomes aware of the toxic culture of the town, with the sons of wealthier citizens indulging in the gang rape of girls from the working class. As she tries to help a recent victim, she becomes a target herself and runs into an establishment which protects perpetrators and holds victims in contempt. Jodrell avoids the sleazier pitfalls of the rape-revenge genre, intelligently dissecting the issues of economics and class which support a hyper-masculine culture which thrives in a social backwater.

Alex Proyas was a successful maker of music videos in the ’80s, which was no doubt why he was tapped to direct The Crow (1994). But it turns out that this was actually his second feature. Seven years earlier, he and a group of enthusiastic collaborators had shot a low-budget fantasy in the popular Broken Hill area of New South Wales (location of Wake in Fright, Razorback, The Road Warrior, Priscilla Queen of the Desert and literally hundreds of other productions). Although Proyas had only begun making music videos the previous year, the visual style of Spirits of the Air, Gremlins of the Clouds (1987) reflects that genre; strikingly photographed by David Knaus, the desert location becomes a fantasy landscape enhanced by some very effective foreground miniatures to suggest that the story takes place after some devastating catastrophe. Proyas’ script brings to mind the imaginative absurdity of Richard Lester’s The Bed-Sitting Room (1969). Years after civilization has been devastated, a brother and sister live in the middle of nowhere; one day a wandering stranger arrives to disturb their routine and while the sister believes him to be a demon, the brother helps him build a flying machine to escape over the mountain range to the south. The characters are eccentric, the visuals loaded with symbols whose meaning is seldom clear (there are a lot of crosses), but there’s a dream-like quality which is appealing and the performances are never less than interesting. These people might live just outside the frame of Mad Max, demented survivors of catastrophe, while Proyas casts a net which snags elements as disparate as Tarkovsky (all that religious imagery), Altman (the flying machine recalls Brewster McCloud [1970]) and Terry Gilliam (a lot of colourful eccentricity).

For the company’s first 4K UHD release, American Genre Film Archive has restored a movie which has had a surprisingly low profile despite being made by a number of George A. Romero’s proteges. Dusty Nelson’s Effects (1979) features Joe Pilato, John Harrison, Tom Savini, John Sutton, Debra Gordon and others who had worked (and would work again) with Romero on a number of projects both in front of and behind the camera. Harrison plays a director making a low-budget horror movie in a remote house; Pilato is his cameraman; Savini is an obnoxious crew member. One evening, the director shows a few of the crew what he initially purports to be an actual snuff movie, though in light of their distaste he quickly says it’s a joke. But it soon becomes clear that there’s another, hidden crew filming the production, and cast and crew are being targeted and knocked off one by one. Nelson and co-writer William H. Mooney take a low-key approach, more interested in creeping suspense and a self-referential look at the filmmaking process than displays of gore. The film may have been too serious for its own good, approaching the subject as drama rather than exploitation. This release provides an interesting footnote to the Pittsburgh scene dominated by Romero.

The first (and so far only) feature by Greek filmmaker Yannis Veslemes, the enigmatically titled Norway (2014) is a stylish rethinking of the vampire genre which would make a good companion piece for Jim Jarmusch’s Only Lovers Left Alive (2013). Vampire Zano (Vangelis Mourkis) takes a train to Athens in 1984 and descends into the city’s club culture, where he proves to be an impressive dancer, and connects with a prostitute, drug dealers and another vampire. Light on narrative, Norway is rich in atmosphere thanks to Hristos Karamanis’s evocative cinematography and director Veslemes’s own score, which gives the club scenes a lot of energy.

Documentaries

As an obsessive collector, I’m always interested in movies which explore the impulse (the greatest being Allan Zweig’s Vinyl [2000]). Perhaps it’s not surprising that this subject seems to attract obsessive filmmakers, producing somewhat ragged but passionate movies. So I enjoyed both Dan Kinem and Levi Peretic’s Adjust Your Tracking: The Untold Story of the VHS Collector (2014), whose title is self-explanatory, and James Westby’s At the Video Store (2019), which is steeped in nostalgia for a lost cultural moment.

Although more subdued and (perhaps) thoughtful than Jay Cheel’s previous documentary, Beauty Day (2011), How to Build a Time Machine (2016) is another study in obsession – or rather dual obsessions. Stop-motion animator Rob Niosi spends years meticulously constructing a full-scale replica of the time machine from George Pal’s 1960 film, using the finest materials (and spending what appears to be a huge amount of money), while Ronald Mallett was inspired by reading H.G. Wells’ novel to become a theoretical physicist in the hope of being able to build an actual time machine in order to go back and save his father who died of a heart attack when Mallett was ten. Somewhat echoing the films of Errol Morris, Cheel’s documentary explores the intersection between reality and imagination and the ways in which the latter might transform the former.

Reality and imagination also intersect in Once Upon a Time in Uganda (2021), Cathryne Czubek’s documentary about the hand-made action movies of Isaac Nabwana, aka Nabwana I.G.G., who established a production company in an impoverished ghetto in Kampala, using small consumer video cameras, a home computer and the enthusiastic help of his neighbours. The documentary focuses on the relationship between Isaac and Alan Hofmanis, who abandoned his problems in New York, flew to Uganda, and connected with Isaac purely on the strength of having seen the trailer for Who Killed Captain Alex? (2010) on YouTube. Hofmanis became Isaac’s partner, managing to promote his Wakaliwood productions around the world. Czubek’s film is much more polished than those it’s about, but while the story is fascinating her telling of it raises some questions – not least using Alan Hofmanis as her way in, a choice which inevitably raises issues of colonialist appropriation of something decidedly rooted in the local community. Luckily Isaac is a very strong presence who asserts his own interests – late in the film when the pair have a falling out, it’s because those interests clash with Alan’s view of the direction the company should be taking. Butt-hurt, Alan returns to New York to sulk and Czubek follows him, as if his feelings are what really matter. He eventually returns to Uganda and the pair resolve their differences, but the earlier tone of shared pleasure in creation is never quite recovered. In addition, parts of the documentary, including the opening section covering Hofmanis flying to Uganda and connecting with Isaac, are obviously staged and played for comic effect – it’s not clear at what point in the real story Czubek became involved and started filming, but no doubt those questions are answered in some of the disk extras. What really matters though is Isaac himself and the ambition which drives him to make elaborate movies essentially for his neighbours (with budgets around $200), which have managed to find a global audience.

Animation

Three very different styles of animation are on display in a pair of Eastern European movies from the ’80s and a recent one from the U.S. The closest to classical cel animation is Heroic Times (1983) by Hungarian filmmaker József Gémes, based on a 19th Century epic poem about Medieval power struggles. The painterly style is rich and dense, while the imagery alternates between static art over which the camera tracks and pans and some gorgeously fluid animation. The narrative is at times confusing, and Gémes repeats images perhaps too often making the film feel padded, but the artwork is often quite breathtaking.

The Pied Piper (1986), by Czech filmmaker Jirí Barta, retells the familiar story with stunning stop-motion animation, bringing to life wooden puppets on elaborate sets which evoke the extremes of German Expressionism. With sparse dialogue in an imaginary language, the film relies on its imagery and the familiarity of the narrative to tell the story of a town plagued by rats, whose council hires the piper to lure the rodents away only to cheat him of payment. In revenge, he lures away the children, subjecting them to the same fate as the rodents. Although commissioned to produce a film for children, Barta’s approach is incredibly dark and grim, rife with violence (including rape and murder). The monstrous members of the town’s council reminded me of the Skeksis in Jim Henson’s The Dark Crystal (1982), but there’s no counterbalancing lightness like the Mystics or Gelflings – by the end, the town’s population is transformed by greed into a horde of rats again lured to destruction by the piper, the only survivors being an old fisherman and a young baby, neither of whom has been corrupted.

At the opposite end of the scale from Barta’s remarkable craft is the hand-made cut-out animation of Eric Power’s Attack of the Demons (2019), whose style seems to owe as much to early Richard Linklater as it does to Sam Raimi and South Park. Three former high school friends now approaching thirty return to their small mountain home town in the mid-’90s on the eve of the annual Halloween festival; meanwhile the priestess of a pagan cult is performing blood sacrifices in the woods, preparing to infect everyone with demonic possession and raise a powerful demon. The pop-culture-savvy trio escape the infection and head for a remote cabin where they have a big showdown with the priestess and the monster she’s conjured. Engaging characters, lots of references to movies, and seemingly naive animation loaded with gross-out gore keep the movie zipping along for an entertaining seventy-five minutes.

*

Recent Vinegar Syndrome and partner releases not yet watched: The Apocalypse Tetralogy (Piotr Szulkin, 1980-85), Sick of Myself (Kristoffer Borgli, 2022) Guest House Paradiso (Adrian Edmondson, 1999), The Demon Rat (Ruben Galindo Jr, 1992), Red Sun Rising (Francis Megahy, 1994), Arnold (Georg Fenady, 1973), Evil Judgment (Claudio Castravelli, 1984), Ghost Nursing (Wilson Tong, 1982), An Eternal Combat (Thomas Yip, 1991), Curse of the Screaming Dead (Tony Malanowski, 1982), Visitors from the Arkana Galaxy (Dusan Vukotic, 1981), Hitman’s Hero (Mark Savage, 2000), Day of the Panther/Strike of the Panther (Brian Trenchard-Smith, 1988), We Kill for Love (Anthony Penta, 2023), Vengeance is Mine (Michael Roemer, 1984), Tower: A Bright Day/Monument (Jagoda Szelc, 2017/2018), Death in Brunswick (John Ruane, 1990), Girlfriend From Hell (Daniel Peterson, 1989), Video Murders (Jim McCullough Sr, 1988), Dirty Money (Dents Arcand, 1972), The Harbinger (Andy Mitton, 2022), The Heart is Deceitful Above All Things (Asia Argento, 2004), Midnite Spares (Quentin Masters, 1983), Rimini (Ulrich Seidl, 2022), The Tortured Soul Trilogy (Michael W. Johnson, 1992-2004), Video Diary of a Lost Girl (Lindsay Denniberg, 2012), Savage Harvest (Eric Stanze, 1994), Death Magic (Paul Clinco, 1992)

*

Still to come: releases from ClassicFlix, Second Sight, Severin, Indicator…

Comments