Fall 2023 viewing, part three

The central conceit of Laurence Sterne’s Tristram Shandy, the remarkable comic novel which provides a startling post-modern deconstruction of a literary form which had not even been fully invented when it was first published in the mid-18th Century, is that in telling his own life story, Tristram has to keep doubling back to relate something important which played a crucial part in what he’s about to tell you … so that by the end, after almost eight-hundred pages, he hasn’t quite reached the moment of his own birth. I’m not making any claims here for an equivalence in this blog, but nonetheless however much I write I do seem to fall further and further behind in my on-going account of my movie-viewing. In order to keep up, I’d have to force myself not to watch so much; the alternative is to accept that it may not be worth writing about a lot of what I do watch – which given my habits as they’ve evolved over the past few years, may be the wiser choice.

But there’s another dimension to this paradox which I have probably avoided thinking too deeply about – it’s easier to write about the less demanding movies I watch, so I often put off saying anything about movies which require more thoughtful analysis and devote an inordinate amount of space to what I might consider less worthy movies (though I do enjoy watching them!). More worrisome is the thought that maybe I’m losing the capacity to tell the difference. Here, I continue my brief survey of what I’ve been watching over the past couple of months

Stitches (Conor McMahon, 2012)

There’s not a lot to say about Conor McMahon’s horror-comedy Stitches (2012), except that I wanted to like it more. The set-up is promising – an obnoxious clown is accidentally killed by the kid’s at a birthday party who aren’t impressed with his lame magic tricks; years later, after the kid’s have grown up, he rises from the grave and returns for another birthday party to kill his tormentors. But it’s all pretty routine as a parody of the typical slasher, with only odd hints of a secret society of clowns pointing at the potential for something more interesting.

Ambulance (Michael Bay, 2022)

I hadn’t really heard anything about Michael Bay’s Ambulance (2022) – in fact I initially confused it with Antoine Fuqua’s well-reviewed The Guilty (2021) because they both star Jake Gyllenhaal. A remake of a 2005 Danish thriller, it’s loaded with Bay’s ridiculous excesses, amped up even more than usual thanks to lightweight cameras attached to agile drones which swoop and dive and circle the action endlessly. That action involves two “brothers”, one white and one Black, one a criminal, the other a struggling family man, who become involved in a bank robbery which goes very wrong and end up hijacking an ambulance carrying a cop wounded during their attempted escape. For more than two hours, the movie mostly takes place in the speeding ambulance being pursued by cops determined to kill the robbers, while the paramedic inside strives to keep the cop alive (including performing risky surgery guided by a former boyfriend over Zoom). It’s very absurd, with the overblown action in constant tension with what seems to be an attempt at an intimate character study.

Nightmare Alley (Guillermo del Toro, 2021)

I’d avoided Guillermo del Toro’s remake of Nightmare Alley (2021) both because I’d so disliked The Shape of Water (2017) and because his entire approach to movie-making seemed antithetical to the grungy noir of William Lindsay Gresham’s 1946 novel and Edmund Goulding’s 1947 adaptation starring Tyrone Power. But I do like much of del Toro’s work, so I finally decided to take a look – and it was everything I’d feared, big, over-designed, slick and colourful and ultimately unable to sink into the story’s grimy heart. Like The Shape of Water, it’s all surface, a shell constructed from shimmering images which conceal the absence of substance. The look of the movie, courtesy of Tamara Deverell’s design and Dan Laustsen’s cinematography, works against the existential despair of Gresham’s plunge into the sheer awfulness of the American dream of individual success which destroys everyone and everything that gets in its way. Del Toro is a fabulist who can’t help looking for beautiful images to wrap around his chosen material – but there was a time when he managed to balance those images with a comprehension of the horror bubbling below the surface – particularly in Cronos (1992), The Devil’s Backbone (2001) and Pan’s Labyrinth (2006), that is those movies rooted in his own cultural background, but even as recently, to some degree, as in Crimson Peak (2015). At his best, he has been able to find a point at which artifice and reality work together and reinforce each other, but in some of his bigger movies the artifice sweeps away reality, as it does here.

Underwater (William Eubank, 2020)

I got suckered into watching William Eubank’s Underwater (2020) after watching Paton Oswalt’s enthusiastic appreciation on Trailers From Hell, in which he offered a big spoiler which definitely piqued my interest. The movie is set in a deep-sea mining installation which is damaged by what seems to be an earthquake. But as a handful of survivors try to make their way to escape pods – which involves crawling through wreckage, swimming through flooded tunnels, and finally walking across the ocean floor to another part of the installation – they realize that the collapsing structure is under attack by unknown creatures. Oswalt’s spoiler was identifying the big bad as none other than H.P. Lovecraft’s Cthulhu, awakened from his sleep in R’lyeh by the mining operation. That was enough to get me excited – plus the movie stars Kristen Stewart, whom I have some interest in after seeing her quirky performance in David Cronenberg’s Crimes of the Future (2022).

The movie itself is tight and efficient, well-paced, and technically quite impressive (unlike James Cameron’s The Abyss [1989], which was shot in a huge water tank, this was shot “dry for wet” on soundstages, which means most of the watery environment was created with CG in post-production), but I waited in vain for the script to reveal what Oswalt had told me was there – it never comes; no hints of Great Old Ones, no awareness among the dwindling cast that they’re up against an ancient god … what we get seems more like the giant cephalopod from Stephen Sommers’ Deep Rising (1998), just a huge tentacled sea creature looking for food. I guess you might be equally justified in saying that the creature which attacks the cruise ship in Sommers’ movie is Cthulhu, but you’d just be imposing something which isn’t evidenced anywhere in the script. So Underwater turns out to be just an efficient B-movie which goes through fairly familiar motions, for me at least never transcending its formula.

Crimes of the Future (David Cronenberg, 2022)

Speaking of Stewart and Cronenberg, I watched Crimes of the Future again because I bought the new Second Sight collector’s edition (even though I already had the essentially bare-bones region A Blu-ray). Like all the company’s collector’s editions, it comes in a slipcase with a substantial book and the disk is packed with extras. Along with multiple cast and crew interviews, a video essay about Cronenberg’s long-running interest in the mutability of bodies, a making-of and a very brief short film by Cronenberg, I was particularly interested in the commentary track delivered by Caelum Vatnsdal. I’ve known Caelum since my days at the Winnipeg Film Group back in the early ’90s; he was still in his teens when I gave him a hand making a short film called Kundalini Unbound, and since then, although he made other films, he’s become a more interesting writer, with two editions of his They Came From Within: A History of Canadian Horror Cinema and a wonderful biography of the late, great Dick Miller. He’s contributed featurettes to several Arrow releases in recent years, but this is his first commentary; I’m envious that he conveys a lot of information about the production, Cronenberg’s career, the cast and crew, as well as a critical reading of the film, all in a relaxed, conversational tone.

And speaking of Second Sight, Crimes of the Future was just one of the new releases I ordered from them. I haven’t yet tackled their editions of Lucky McKee’s May (2002), David Robert Mitchell’s It Follows (2014) or Peter Weir’s Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975), but I did watch three others, two of which are upgrades from older DVDs, with the third being new to me.

Session 9 (Brad Anderson, 2001)

Brad Anderson’s Session 9 (2001) always appealed to me more for its location than for its story – it was shot primarily in the sprawling, derelict maze of the Danvers State Hospital in Danvers, Massachusetts, a massive psychiatric facility originally built in the 1870s and added to over the years before finally being closed down in 1992 (parts of it were eventually transformed into an apartment complex in the ’00s). Filled with debris and the detritus of a century of human torment, these buildings supplied a huge amount of production value for the relatively low-budget project in which a small team of contractors are hired to strip out all the asbestos used in the original construction. The team seem to be infected by the miasma of insanity which permeates the very bricks and plaster, with some entity gradually picking them off one by one as the days pass.

The cast is excellent – Peter Mullan as the boss, David Caruso as his partner, Josh Lucas, co-writer Stephen Gevedon and Brendan Sexton III as the crew – but I’d previously found the story too vague, relying on the building itself to carry too much of the narrative load. For some reason, it worked for me better on this viewing, but my perspective was considerably changed after the fact by a featurette in which Alexandra Heller-Nicholas analyzes the film’s gender politics, something I was only vaguely aware of as I watched the feature itself, but which seems absurdly obvious once it’s pointed out. The subtext running through the film – and through the history of Danvers itself – is the violence inflicted by men on women and the interpretation imposed by men on the roots of that violence; that women themselves provoke it, that it’s in their nature to cause men to lash out and “correct” their inherent defect.

One of the men finds a room full of files and tape-recorded therapy sessions and spends time during the job listening to tapes which gradually reveal the traumatic experiences of a young woman named Mary Hobbes, while the film cycles back repeatedly to reveal what’s behind the boss’s increasingly apparent psychological collapse, an appalling act of domestic violence which everything that happens is an attempt to cover up. The decaying hospital is conflated with the boss’s disintegrating mind, both institution and individual having perpetrated unforgivable violence against women.

Dog Soldiers (Neil Marshall, 2002)

Issues of masculinity also show up in Neil Marshall’s Dog Soldiers (2002), though in a more recognizable genre package. Marshall made an impressive writing-directing debut with this story of an army unit on a training mission in the wilds of Scotland who discover that they’re being used as bait by a ruthless officer who’s determined to capture what appears to be a werewolf. Things quickly go wrong when it turns out there’s actually a whole werewolf clan; the unit (and the officer) take shelter in a remote farmhouse where they’re besieged during a single gruelling night during which almost everyone eventually dies (or is turned into a werewolf after being bitten). Marshall sets up a contrast between the men of the unit, mutually supportive and self-sacrificing, and the officer who’s devoid of empathy and gives in to the animal savagery which is already inside him. Tightly constructed, with an excellent cast and impressive creature effects, Dog Soldiers is a fine addition to its sub-genre.

Frontier(s) (Xavier Gens, 2007)

I’m more ambivalent about Xavier Gens’ Frontier(s) (2007), an extremely graphic example of extreme French horror. The political subtext is obvious, with immigrants pitted against fascists as a fraught election seems poised to put a Right-winger like Le Pen into power, but it’s easy to forget the larger implications as the movie descends into familiar genre tropes and an excess of gore. During riots in Paris triggered by the election, a group of immigrants rob a bank and head out of the city in two cars. The first, carrying a pair of obnoxiously sexist men, arrives at a remote country inn where they insult the owners, fuck the help, and abruptly find themselves in a slaughterhouse where a hulking Leatherface type butchers the guests to feed the family. Unaware of all this, the second car arrives with pregnant Yasmine (Karina Testa) and her boyfriend, and we settle in for a more protracted reprise of what happened to the first pair.

The cannibal family is led by an aging Nazi patriarch whose concern is the continuation of the clan, which is declining as inbreeding produces defective offspring. Although Yasmine is not good Aryan stock, she will nonetheless make a fine breeder, so she’s spared the bloody fate of her companions, giving her an opportunity to fight back and attempt escape. As it goes on, Frontier(s) becomes increasingly numbing with its relentless brutality and its extremely unpleasant depiction of defective human nature – something it shares with The Divide, the feature Gens shot here in Winnipeg in 2011. At the level of craft, his skills are undeniable, but it’s debatable how well his movies work either as political commentary or entertainment.

*

It took two months for Severin to ship my (expensive) order from their mid-summer sale and I’ve only got around to watching two of the four releases so far. Still to watch are Lucio Fulci’s The Psychic (1977), a 4K upgrade of the film which serves as a kind of transition from his gialli to the full-blown horror which began with Zombie in 1979; and David Winters’ The Last Horror Film (1982), notable as the re-teaming of a typically deranged and sweaty Joe Spinnell and Caroline Monro, who had starred together in William Lustig’s Maniac two years earlier, and perhaps more interestingly at this distance for having been shot during the 1981 Cannes Film Festival, adding a documentary quality to its story of a deranged fan stalking a horror-movie star.

Bad Biology (Frank Henenlotter, 2008)

What I have watched is Frank Henenlotter’s Bad Biology (2008), his first feature since Basket Case 3 (1991) and a return to the gross-out extremes of his early movies with their mix of twisted sex, body horror and gore. Rough around the edges, with uneven performances and provocative lapses of taste, it somehow manages to be both offensive and oddly sweet-natured – the latter mostly due to the game performance of Charlee Danielson as photographer Jennifer, who has multiple clitorises and a hyper-metabolism which makes her orgasms so intense they’re likely to kill her lovers; she also produces mutant offspring soon after sex, tossing the newborns in the trash as she moves on. There’s also Batz (Anthony Sneed) who has an anatomical problem of his own, having had his penis severed at birth and reattached. A lifelong regime of steroids and other drugs has made it enormous and sentient; when Jennifer gets a glimpse of it, she thinks she’s found the ideal solution for her own problem, but all the excitement eventually provokes it to break free and go on a rampage. While Bad Biology taps into elements from Henenlotter’s earlier movies – Basket Case (1982), Brain Damage (1988), Frankenhooker (1990), all of which may be better movies – it has an odd charm and some genuinely funny sequences.

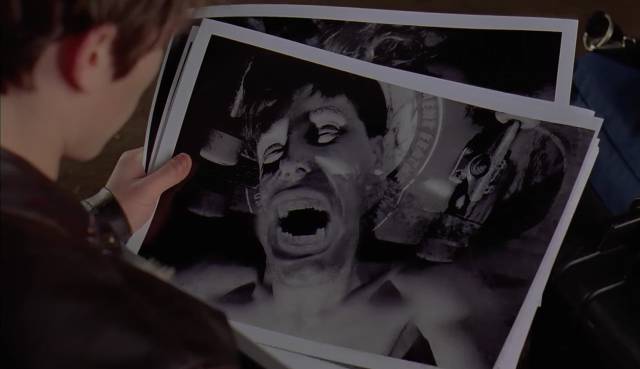

Nightmare (Romano Scavolini, 1981)

I was braced for something extreme with Romano Scavolini’s Nightmare aka Nightmares in a Damaged Brain (1981), notorious as one of Britain’s video nasties, though I should know by now that the arbitrary list cooked up by the censorious authorities includes a wide range of movies, many of which could barely be considered offensive even back in the early ’80s let alone now after we’ve seen so much worse in the mainstream. There is certainly violence and gore in Scavolini’s psycho-thriller, but nothing beyond what you might see in a George A. Romero movie. What you do see, though, is some moments of violence in proximity to children (a flashback to which the movie returns repeatedly has a boy killing his father and his lover with an axe during sex), which is no doubt the main reason it was banned.

A mental patient prone to terrifying nightmares (rooted in that flashback) is undergoing experimental therapy to “cure” his psychotic tendencies. Deemed fit, he’s released, gets himself worked up in some Times Square sex shops, then heads down the coast to Florida, apparently stalking a woman and her young kids, but actually tracking his own past and the trauma which made him insane. There’s a grubby tone, some long lethargic stretches, and then two-thirds of the way through a couple of children are killed and by the end the man’s madness has been passed on to another child. It’s definitely seedy, but Baird Stafford gives an interesting performance as the damaged protagonist. More interesting was the subsequent fate of the movie and Severin includes a supplementary disk featuring a documentary about British video distributor David Hamilton-Grant, who was actually convicted and sent to prison for releasing Nightmare on VHS in an unauthorized cut. The disk also includes four movies directed by Hamilton-Grant – three hour-long sex comedies and a bizarre (racist) short treating Idi Amin as a comic buffoon.

Private Crimes (Sergio Martino, 1993)

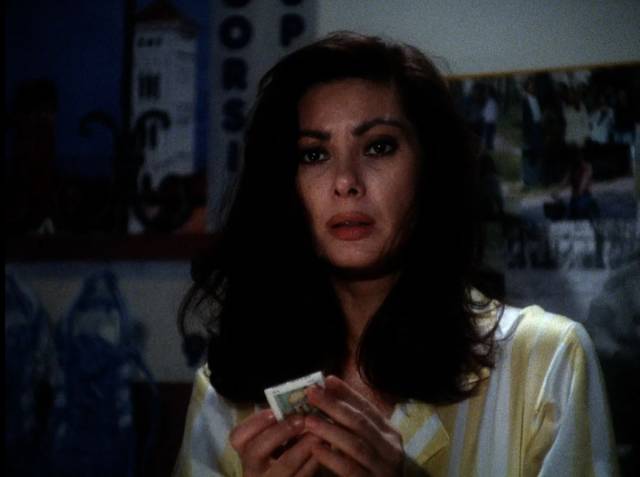

Sergio Martino was a major figure in Italian genre cinema throughout the ’70s and ’80s, moving from gialli to poliziotteschi to westerns, cannibal and post-apocalyptic action movies, and then increasingly into television in the latter part of his career in the ’90s and ’00s. While familiar with many of his features, from The Strange Vice of Mrs. Wardh (1971) to American Rickshaw (1989), I hadn’t encountered any of his TV work until Severin’s release of the 1993 mini-series Private Crimes (Delitti Privati) – four feature-length episodes totalling six hours. Written by Laura Toscano and Franco Marotta, whose work together goes back to the mid-’70s and movies like Massimo Dallamano’s The Night Child (1975) and Enzo G. Castellari’s The Inglorious Bastards (1978), and produced by and starring Edwige Fenech, the series has pretty impeccable credentials along with an excellent multi-national cast.

The story blends a murder mystery with family melodrama, with Fenech as a reporter who’s tragically drawn into the investigation of a murdered aristocratic businessman when her own daughter also turns up dead. Dealing with her grief by pursuing her own search for the truth, she feels herself threatened as other murders follow and she receives anonymous letters with cryptic warnings. As more and more secrets are uncovered, casting an unsavoury light on the dead man’s family – dominated by a matriarch played by Alida Valli, who is far more concerned with protecting the family reputation than actually finding the killer – the reporter is confronted with the knowledge that her relationship with her daughter wasn’t what she thought it was.

Martino keeps things moving with an agile camera as he juggles multiple threads, leading to a sad climactic reveal of the killer’s identity and motive, but some of the threads remain loose (the motive for the anonymous letters; occasional intimations of the supernatural), suggesting that the story has been padded to fill four episodes. But it’s a polished piece of work and the cast easily maintain viewer engagement. It also looks excellent in a 2K scan from original 16mm elements spread across two disks, with a Kat Ellinger commentary on the first episode and new interviews with Fenech and Martino.

Danza Macabra: The Italian Gothic Collection, Volume One

I might have neglected Severin’s four-disk Danza Macabra set because it didn’t include any movies of the stature of Damiano Damiani’s The Witch (1966), which had been the high point of Arrow’s Gothic Fantastico set released in 2022. But looking back, the four titles chosen by Severin are actually on a par with the other three in Arrow’s set. Although less successful internationally than the spaghetti western, giallo and poliziottescho, the Gothic forms a deep vein in Italian genre cinema running from the mid-’50s into the ’80s, most obviously kicked off by Mario Bava with Black Sunday in 1960, following his unofficial directing debut on I Vampiri (1957), which he completed after Riccardo Freda walked off the set.

With the recent 4K restorations of Renato Polselli’s Delirium (1972) and Black Magic Rites (1973), the most significant movie in the set is probably his The Monster of the Opera (1964), reworking his own earlier The Vampire and the Ballerina (1960), which had actually been released a few months before Black Sunday. In both films, a troupe of dancers find themselves rehearsing a show in a gloomy old building which happens to be home to vampires. I haven’t seen the earlier movie, but The Monster of the Opera seems to provide a bridge between the familiar old school Gothic and Polselli’s deranged movies of the ’70s, its more conventional elements – the old building haunted by a vampire, the suggestion that the nightmare-haunted heroine is a reincarnation of the bloodsucker’s lost love – are rendered with some flamboyantly expressive camerawork.

This is followed by a couple of more obscure movies. Garibaldi Serra Caracciolo’s The Seventh Grave (1966) is a variation on the Old Dark House formula, with a group of people gathered at a decaying mansion in 19th Century Scotland where it’s reputed that Sir Francis Drake’s treasure is hidden. There’s a spooky seance and bodies begin to pile up. This was the only movie directed by Serra Caracciolo, and it’s perfunctory at best, adding little to a familiar formula.

The Gothic tends to lose something with the switch from black-and-white to colour, so it may be that which makes Jose Luis Merino’s Scream of the Demon Lover (1970) seem less atmospheric. Or maybe it’s just the script and the slow pace. An attractive biochemist arrives at a castle to assist the Baron with his experiments, about which he’s rather cagey – his ultimate aim is to revive his dead brother. Meanwhile local authorities are investigating murders in the neighbourhood and the new assistant is tormented by nightmares about a deformed figure attacking her … but are they really dreams or something more sinister?

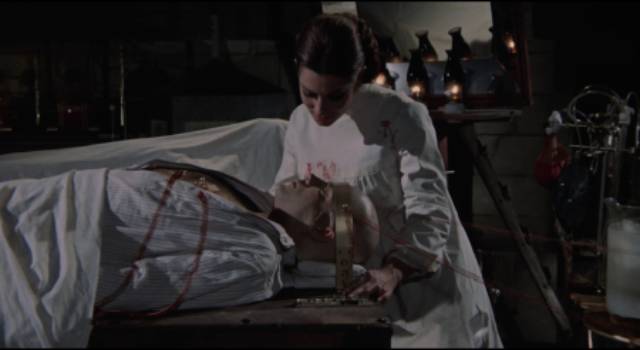

In the ’60s and early ’70s actor Mel Welles (Mr. Mushnik in Roger Corman’s Little Shop of Horrors [1960]) co-directed a number of movies in Europe, the last being Lady Frankenstein (1971), notable for the presence of Joseph Cotten in the midst of his late-career run of horror movies. Naturally, he plays the Baron who’s dabbling in unholy experiments, who is surprised when his daughter (Rosalba Neri) returns home as a newly accredited surgeon and tells him she wants to assist in his work. When he finally accomplishes his goal of building a man out of dead parts, wouldn’t you know it but the brain is defective and the creature kills him and flees to wreak havoc in the neighbourhood. His daughter insists on carrying on with the help of dad’s assistant; he has fallen in love with her and she wants to put his brain into the hunky gardener. It takes the local police in the form of Mickey Hargitay to sort out the mess. Pulpy, gory and a bit perverse, Lady Frankenstein almost seems like a trial run for Paul Morrissey’s Flesh for Frankenstein (1973).

Along with excellent transfers, the four disks are loaded with extras: commentaries, interviews and video essays, and bits of ephemera (including a Lady Frankenstein photo-novel).

The Devil’s Game

Somewhat related, I also finished watching Severin’s two-disk The Devil’s Game set, six adaptations of 19th Century stories made for Italian television in 1981. I previously wrote about La venere d’Ille, the final film directed by Mario Bava (collaborating with his son Lamberto), which was the main reason I bought the set. That, along with Giulio Questi’s The Sandman (from E.T.A. Hoffman’s story) and Piero Nelli’s The Perfect Presence (from a Henry James story), were all shot on film, but only the Bava episode was scanned from a print – the others only survive as SD tape masters. The other three episodes (on disk two) were all shot on tape in studios with sparse sets, which give them a very different feel, theatrical rather than cinematic, and in a couple of cases almost abstract. Marcello Aliprandi’s The Dispossessed Hand (based on a story by Gerard de Nerval) is limited by its staginess, while Tomaso Sherman’s The Bottle Imp (from Robert Louis Stevenson’s story) has the merest suggestion of sets as performers act out events being described by an on-screen narrator. The final episode, Giovanna Gagliardo’s The Dream of Another (based on an H.G. Wells short story) also uses minimal sets, but tells the story in a more straightforward way. The series as a whole provides a glimpse of interesting and varied approaches to literary adaptation on television, though some episodes feel padded (The Bottle Imp at 88 minutes is a real slog to sit through). The quality reflects the limitations of production and the survival of five episodes only on SD; and the only extras are those related to La venere d’Ille, which I’ve mentioned previously.

Next: more from Arrow, a couple of Eureka releases and a few from Kino Lorber.

Comments