Fall 2023 viewing: Arrow Video

My recent Arrow viewing has included a couple of new releases along with a couple which have been sitting on the shelf for a while, waiting for me to get around to them.

Crash (David Cronenberg, 1996)

I finally opened the special edition of David Cronenberg’s Crash (1996) after re-watching Crimes of the Future – there’s an ancillary connection in addition to them both being among Cronenberg’s best work, because each disk features an extra by fellow Winnipegger Caelum Vatnsdal; while Crimes has his first commentary, Crash includes a featurette on the use of architecture and location in the filmmaker’s work.

In the 1990s, in an apparent act of hubris, Cronenberg adapted two novels deemed unfilmable. Although I should take another look, Naked Lunch (1991) has always drawn a mixed response from me; maybe this is partly due to my minimal experience of William S. Burroughs’ work – I’ve only read one of his novels (Cities of the Red Night), which I found mildly interesting but not particularly engaging. I do have a CD set of Burroughs reading excerpts from Naked Lunch and the flow of strange imagery delivered in his distinctive voice has a kind of hypnotic effect, more poetry than narrative, and I’ve always enjoyed his brief appearances in movies like Muscha’s Decoder (1984) and Gus Van Sant’s Drugstore Cowboy (1989). I can’t gauge Cronenberg’s adaptation relative to the book, but as a movie it falls short for me because, unlike the director’s other films – no matter how outrageous the concept – it seems ungrounded in the real world, so the weirdness just kind of floats there for its own sake, rather than reflecting back on recognizable experience.

In this, the work of J.G. Ballard seems far more amenable to the Cronenberg treatment. Like Cronenberg, Ballard is fascinated by the intersection between the human and technology and the ways in which the latter transforms the former. Like Cronenberg, Ballard approaches his material with a cool, almost clinical attitude, setting up situations and then watching them unfold with the dispassionate interest of a scientist. And of all Ballard’s books, Crash (published in 1973) seems the most apt for Cronenberg’s purposes; here’s a study of people who embrace their transformation through literal collisions with technology. Our existence has become so entwined with the automobile, a device fraught with potential danger, that there are few options for a rational response to the possibility of injury or death – to live in constant fear or embrace violent transformation.

Cronenberg’s challenge was to take Ballard’s clinical study of the pathology of automobile fetishism and dramatize it in a way which makes its disturbing extremes comprehensible. To what degree he succeeded is apparently debatable, given the very mixed, and frequently hostile, critical and audience response to the film when it was released. Although it’s arguable that the hostility itself testifies to his success – many were disturbed by what the film had to say and in rejecting its implications rejected it as a valid piece of cinematic art. There were accusations of pornography – it is, after all, the most sexually explicit movie in the Cronenberg canon, at times uncomfortably so as it pushes hard against the limits of what popular culture deems acceptable. The film problematizes sexuality by investing bodily injury with an erotic charge, lingering on scars and damaged flesh, obliterating boundaries both physiological (distinctions between male and female blur, as does the idea of a genital-centred sexuality) and social (class distinctions dissolve, as does the possessiveness of marriage and defined relationships).

When bodies can be disrupted and transformed in a single cataclysmic moment, there is no longer a clearly defined pattern into which individuals can comfortably fit. And once that has been seen and embraced, the pursuit of increasingly dangerous forms of erotic stimulation becomes an imperative. After surviving a crash, commercial director James Ballard (James Spader) finds himself drawn into a sub-culture which shares a common bond through bodily injuries, with their guru Vaughan (Elias Koteas) clandestinely restaging famous fatal crashes for fellow enthusiasts on remote roads. A bond forms between Ballard and Helen Remington (Holly Hunter), who was involved in the same crash, in which her husband died, and with whom he shares an intense sexual relationship which is heightened by occurring in cars in public places.

The combination of crashes and sexual arousal inevitably leads to increasingly dangerous behaviour – the prospect of imminent death amplifies the erotic charge – and Ballard’s wife Catherine (Deborah Kara Unger) feels left behind. The couple’s attempt to reconnect provoked some of the most intense critical outrage which greeted the film. In two separate cars, Ballard and Catherine engage in dangerous vehicular foreplay on a busy highway, with him finally running her off the road; she crashes through a guardrail and plunges down a slope; he pulls over and climbs down, pulling her from the wreck. But somehow she has escaped injury and he comforts her with an assurance that next time she will be hurt and thus enter into the realm of the transformed. The camera cranes up and back as he offers her a little comfort with conventional sex (strangely, when the film was banned in parts of England, this was cast as an act of necrophilia).

Crash is undeniably disturbing, but Cronenberg’s coolly formalist approach makes it difficult to take the accusations of pornography seriously, despite frequently explicit sequences. Like Ballard’s book, the film is a kind of clinical study of a pathology which arises from our use of, and subjugation to, technologies of our own making. Ballard has provided Cronenberg with the ideal vehicle to convey his own key theme of the mutability of flesh and the consequent transformation of identity. We are inextricably entwined with technology and destined to evolve in tandem with the machines we make.

Arrow’s disk, which features a stunning 4K restoration, is packed with extras – a commentary, interviews, Q&As, two brief short films by Cronenberg, and three experimental shorts based on Ballard’s work, plus a 60-page book of essays.

*

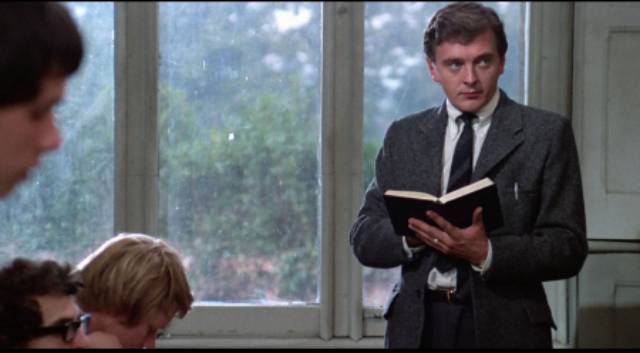

Unman, Wittering and Zigo (John Mackenzie, 1971)

John Mackenzie had a three-decade career which began in television and eventually alternated between television and feature projects. In style and content, his work was all over the place, including Ken Loach-like social issues dramas and American thrillers; while some of this is not without interest, only twice did he rise to the level of producing a masterpiece – in 1977, with his “public service” short Apaches, and again three years later with his brilliant and flawless The Long Good Friday (1980). The latter marked the second stage of his theatrical career after having returned to television following three features in the early ’70s. Two of these remain unavailable, but the second – with the most recognizable title – has just been resurrected by Arrow on Blu-ray.

I assume Unman, Wittering and Zigo (1971) didn’t get much distribution in Canada at the time as I’m sure I would have seen it if given the opportunity. I’d read Foster Hirsch’s review in the Spring 1972 issue of Cinefantastique which piqued my interest, but in the ensuing five decades it never came to my attention on TV or home video, which given the success of The Long Good Friday seems odd. There’s no telling why one movie falls through the cracks while another gains prominence. To add to the puzzle, the film stars David Hemmings, who by the early ’70s was a major star, not least because of the international success of Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blow-Up (1968).

Mackenzie’s film has much to recommend it, but nonetheless contains deep flaws. It’s a satire on the British class system – and one of the key institutions which sustains it – as well as a paranoid thriller (well, perhaps thriller is too strong a word). After a disorienting opening sequence on a clifftop overlooking the sea (the camera tumbles vertiginously over the edge), a group of stony-faced boys in school uniforms watch as a coffin is laid to rest in a bleak country graveyard. And then we are at the Chantrey School for Boys, a small private establishment where John Ebony (Hemmings) has arrived to replace Pelham, a teacher who died mid-term by falling off that cliff. Like Sidney Poitier’s Mark Thackeray in To Sir, With Love (1967), Ebony has given up a dissatisfying career (in advertising) in the hope of making a difference and finding personal satisfaction by teaching. But unlike Thackeray, who takes a job among the underprivileged in London’s East End, Ebony finds himself among wealthy boarding school boys who already understand their privileged position and have no qualms about exercising their inherited power.

When he tries to discipline them, they casually inform him that they killed his predecessor and have no compunctions about doing the same to him if he doesn’t leave them alone. He’s to give them good marks whether they work or not, and act as a go-between taking their bets to the local bookie. Although he initially doesn’t believe them, Ebony finds that he’s trapped by the institutional structures of the school and the society it serves; he tries to tell the headmaster (Douglas Wilmer) what he’s been told, but his concern is quickly dismissed; it’s obviously just the boys trying to provoke him. He’s left to a private battle of wills, with the power of the group outweighing his adult authority.

Complicating the situation, the film layers on some sexual insecurity. One of the pillars of Empire was the male bonding promoted by the boarding school system which fed directly into the colonial service, underpinned by a homoerotic energy which seems to destabilize Ebony’s sense of himself. To make things more unsettling, he doesn’t seem to get a lot of respect from his wife Silvia (Carolyn Seymour, best known to me as Abby Grant in the first season of Survivors [1975]), who isn’t happy about his change of career. With life at home decidedly chilly, he lingers uncomfortably in the boys’ shower room and has a disturbing dream in which they strip him and carry him off into the woods as if for some primal ritual. After the dream, he attempts to assert himself sexually over Silvia, satisfying neither of them, and late in the film the boys trap her in the gym and threaten gang rape, which she barely escapes. Improbably, in the film’s most confounding narrative turn, after the attempted rape, as Silvia insists that she’s leaving the school whether Ebony joins her or not, he abandons her and goes to help the boys whose situation is finally collapsing – the one who instigated the murder of their teacher has disappeared and they now face a genuine possibility of exposure.

Although for much of its running time, the film maintains an effective tension between Ebony and the boys, it stumbles towards the end as it attempts to wrap up both the psychological mystery and the satirical treatment of a corrupt class structure. The fault seems to lie more in the script, adapted by Simon Raven from Giles Cooper’s play, than in Mackenzie’s direction or the performances. The cast is generally excellent, though Seymour has a pretty thankless role; Hemmings plays the mixture of naive idealism and insecurity well and the younger cast, led by the charismatic Nicholas Hoye as the boys’ leader Cloistermouth, are convincing as a group made malevolent by privilege.

In addition to an excellent transfer which serves Geoffrey Unsworth’s cinematography well, the disk includes a commentary, interviews with several cast members, an appreciation by critic Matthew Sweet, and a recording of the original 1958 radio play.

*

Kinji Fukasaku

Up through the 1960s, the yakuza movie was, more often than not, a romanticized story of an outlaw adhering to a chivalrous code which echoed that of the samurai – heroes (or anti-heroes) were torn between a sense of duty and honour and the realities of life as an outlaw. Around the turn of the decade, Kinji Fukasaku did more than anyone else to explode this image, creating a series of films rooted in post-war political and economic realities which conflated ascendant capitalism with ruthless criminal activity. This process began with movies like Japan Organized Crime Boss (1969) and Sympathy for the Underdog (1971), but really took off with Street Mobster (1972), a movie as hard and blunt as its title. Although Fukasaku had worked with star Bunta Sugawara before, this movie launched a hugely influential collaboration similar to Martin Scorsese’s long association with Robert DeNiro.

Arrow’s three-disk Kinji Fukasaku set from 2021 provides a frame for the director’s major project of the ’70s, beginning with Street Mobster (which was quickly followed by the five-part epic Battles Without Honor and Humanity [1973-74]), continuing with Cops vs Thugs (which came in 1975 in the midst of the follow-up trilogy, New Battles Without Honor and Humanity [1974-76]), and concluding with his final crime film, Doberman Cop (1977), before he embarked on a new phase with Shogun’s Samurai and the anomalous Message from Space (both 1978).

These three movies mark an evolution which both transformed a genre and finally exhausted its possibilities. Street Mobster is a brutally nihilistic story devoid of characters with whom the viewer can empathize. Osama Okita (Sugawara) was born on the day of Japan’s unconditional surrender at the end of the Second World War and is infused with hopelessness and rage. He fights, rapes and kills without compunction, lacking loyalty to anyone but himself. We first encounter him as he leaves prison, met by Kizaki (Asao Koike), a lowly criminal who hopes that with his brains and Okita’s brawn they can launch their own crime family. But Okita is uncontrollable and soon he’s provoking the local gangs; although taken under the wing of one family head, he remains wild and the violence escalates. Along the way, he brutalizes women and betrays everyone. Here, the focus remains close to this one dangerous character, without the larger context Fukasaku would bring to Battles Without Honor and Humanity.

In the wake of that epic, Fukasaku complicates the personal story of cop Tokumatsu Kuno (Sugawara again), who helps to maintain the balance of power between two rival gangs in his city. In Cops vs Thugs, despite the clear delineation of sides indicated by the title, those on either side of the law are inextricably tangled up in each other’s business. Crime isn’t suppressed, but rather managed by cops who are friends – even brothers – of the yakuza. However, this balance is threatened as the crime families become increasingly involved in the dealings of large corporations with ties to the city’s political leaders, and crusading police lieutenant Shoichi Kaida (Tatsuo Umemiya) starts to crack down on the ties between cops and criminals, which places new stresses on Kuno’s divided loyalties.

The cycle was already showing signs of strain by 1976, as indicated by the title of that year’s Yakuza Graveyard, which again focused more on a cop than the criminals he was dealing with. The following year’s Doberman Cop, the only Fukasaku film based on a manga, reveals the director no longer taking the genre so seriously. Although it deals with corruption and brutal murders, it has a strain of comedy which works against the darker elements of the narrative. This comes in the form of hick rural cop Joji Kano (Sonny Chiba) who arrives in Tokyo from a remote part of Okinawa wearing a straw hat and carrying a small pig. The latter is intended as a gift for the Tokyo police, to be roasted, while the former signals Kano’s status as a country bumpkin. He might as well also be bare-foot.

The movie is quite obviously modelled on Don Siegel’s Coogan’s Bluff (1968) and the long-running series McCloud (1970-77) based on it, in which a lawman from the rural Southwest ends up in New York where his cowboy ways clash with big city departmental rules. Kano has arrived because it appears that a young woman from his island has been murdered in Tokyo, the body burned so that identification isn’t completely certain. While his poking around annoys the Tokyo police, he realizes that the dead woman isn’t the missing island girl – she in fact is still alive and in the hands of a crime boss who is trying to transform her into a pop star; but, although she has a good voice, she lacks confidence and can’t perform in front of an audience. Kano wants to take her home, though she has no desire to return to village life, and by stirring things up he provokes other murders. Although he eventually resolves the case, and gains the respect of the Tokyo police, he’s inadvertently caused harm and doesn’t succeed is taking the woman home as he leaves the city.

Chiba’s bumpkin act is broad, mocking the genre, and it seems clear that Fukasaku is done with contemporary crime. It’s perhaps significant that Sugawara was replaced with Chiba, though it was only in Fukasaku’s next film, Shogun’s Samurai, that he and Chiba found a more comfortable tone and they would work together multiple times over the next few years.

The three-disk set includes several interview featurettes and a Street Mobster commentary.

*

Enter the Video Store: Empire of Screams

One of Arrow’s biggest recent releases, while it may not represent serious cinema, is loaded with entertainment value. Enter the Video Store: Empire of Screams is a five-disk box set devoted to a collection of movies produced by Charles Band’s Empire Pictures. Band, son of filmmaker Albert Band and brother of prolific soundtrack composer Richard Band, has had a career seemingly modelled on Roger Corman’s, though while Corman had built his own small empire in the days of B-movies and drive-ins, Band rose as home video took off in the late ’70s and ’80s. Like Corman, his philosophy was to keep budgets low and keep the product flowing, pre-selling movies based on promotional materials before anything was actually shot. Also like Corman, Band began as a director and segued more towards producing, though he does continue to direct.

Having formed Empire International Pictures in the early ’80s, Band bought the defunct De Laurentiis studios in Rome where he could keep production costs down and draw on skilled crews to make his movies look much better than you’d expect. That plan lasted only a few years and, having closed the studio, he formed Full Moon Features, a new company which concentrated on the video market, continuing to produce genre movies up to the present. While Band’s productions – both those he directed himself and those he produced for other filmmakers – are wildly varied in quality, his persistence is admirable and along the way he has backed quite a few notable directors and influential genre productions. He promoted the careers of people like David Schmoeller (Tourist Trap [1979], Crawlspace [1986], Puppet Master [1989]), John Carl Buechler, an occasional director best known for his make-up and creature effects, and perhaps most significantly Stuart Gordon, for whom Band produced Re-Animator (1985) and From Beyond (1986) among others.

Arrow’s set spans the brief life of Empire, from 1984’s The Dungeonmaster to 1989’s Robot Jox, with two of the five movies, perhaps not surprisingly, directed by Stuart Gordon, who was the company’s biggest asset. But the first movie in the set showcases no less than seven other directors. Although the first movie released by the company was Band’s own The Alchemist (1983), the first to go into production was The Dungeonmaster (1984), a kind of feasibility test which strings together seven short fantasies, each with a different director. The segments vary quite a bit in concept and execution, but each provides an opportunity to try out a number of effects techniques and to show whether these largely untried filmmakers could handle the technical and creative demands.

To provide an excuse for the individual shorts, a frame story has computer nerd Paul Bradford (Jeffrey Byron) a little too intimate with his sentient computer, arousing the jealousy of girlfriend Gwen (Leslie Wing). While they argue about their relationship, an ancient demon named Mestema (Richard Moll) kidnaps Gwen and challenges Paul to a contest of magic against technology with her as the prize. Paul finds himself going through a series of hellish landscapes where he faces menacing creatures – supplied by optical, animatronic and stop-motion effects – which he rather easily dispatches with his handy wrist laser. The final challenge is essentially a fistfight with Mestema on the edge of a lava pit. Silly and brief, The Dungeonmaster is most interesting as a showcase for what the individual filmmakers could accomplish with very minimal resources, notably the stop-motion of Dave Allen and the creature effects of Buechler. The oddest segment, directed by Band himself, has Paul challenged to survive a performance by hair-metal band W.A.S.P.

There are three different cuts included on the disk, as the movie was presented differently in various markets, with varying amounts of nudity and the segments arranged in different orders.

Most of those involved continued their movie work in various capacities – Buechler as an effects artist, Peter Manoogian as a producer and assistant director, Dave Allen as an animator, Steve Ford as a stuntman and occasional director, Ted Nicolaou as a director, Band as producer, director and distributor. Only Rosemarie Turko didn’t continue with film work.

John Carl Buechler’s directing career was a kind of supplement to his work in effects, most projects affording him an opportunity to exercise that primary talent, beginning with Troll (1986). This was the case when, in the midst of a very busy schedule in the mid-’80s, he directed Cellar Dweller (1987), which was the first produced script by Don Mancini, who would hit it big the next year with Child’s Play. In a prologue, comic book artist Colin Childress (Jeffrey Combs, in a disappointingly brief role) uses an ancient occult text as inspiration for his new project, inadvertently raising a demon which promptly kills him. Decades later, his old mansion is now an art school run by Lily Munster herself, Yvonne De Carlo, who reluctantly admits new student Whitney Taylor (Debrah Farentino). Poking around in the school basement, Whitney discovers Childress’s work and is inspired to draw the demonic character herself … naturally bringing it back to wreak havoc and kill fellow students and others. Rather underpopulated and claustrophobically confined to a few sets, the movie exists mainly as a vehicle for Buechler’s elaborate monster makeup.

Although Empire’s tenure in Rome produced some notable work, financial strains made things rocky for the company towards the end of the ’80s. That didn’t stifle Band’s ambition, though, and he embarked on a couple of large-scale (for the budget) sci-fi movies which ended up tanking the company, to the movies’ detriment as they received such spotty distribution that they couldn’t really find an audience despite some appealing qualities.

The first of these was Peter Manoogian’s Arena (1989), a colourful fantasy comparable to the kind of thing Roger Corman had been doing back at the beginning of the decade with movies like Jimmy T. Murakami’s Battle Beyond the Stars (1980) and Bruce D. Clark’s Galaxy of Terror (1981). In Arena, humans are fairly low in the galactic hierarchy, getting little respect from the dominant species who run a popular MMA-style contest from a huge space station. Lowly cook Steve Armstrong (Paul Satterfield) calls attention to himself when he gets into a fight with an alien and finds himself groomed as a new underdog competitor who faces off against a series of large, elaborate animatronic aliens, becoming a star despite the fights being rigged against him. Essentially Rocky in Space, Arena is undemanding entertainment which goes through familiar sports movie paces with the added attraction of some impressive on-set creature effects.

This was followed by Stuart Gordon’s Robot Jox (1989), influenced by Japanese manga and television series featuring giant robots (and possibly one of the inspirations for Guillermo del Toro’s Pacific Rim [2013]). Faced with the prospect of wars which could wipe out the world, international agreements have established a controlled dispute resolution system in which pilots in giant robots face off in gladiatorial combat in remote areas. Written by notable science fiction author Joe Haldeman (whose award-winning 1974 novel The Forever War would’ve made an excellent movie), the script is solid pulp sci-fi with Cold War elements and familiar personal conflicts among the characters – traitors, a hero who’s lost his nerve, a woman pilot held back by sexist attitudes. Gordon keeps things lively, but the real fun is in the large-scale miniatures and Dave Allen’s stop-motion robots. The action may lack the elaborate detailing of Pacific Rim, but this was all done pre-CGI with actual models shot in the desert.

Robot Jox is effective within its budgetary limitations, though not Gordon’s best work to be sure – that would be the fifth movie in the set, Dolls (1986), about which I’ve written before. Although Re-Animator and From Beyond are more popular with his fans, I like this strange fairy tale more. A dark, exceedingly creepy child’s nightmare, it has atmosphere to spare and a streak of dark humour thanks to Guy Rolfe and Hilary Mason as the charmingly sinister old toy-makers who transform annoying guests into dolls which do their malevolent bidding. Made simultaneously with From Beyond at the studios in Rome, Dolls has impressive production values, with excellent photography by Mac Ahlberg and terrific effects by a large team which included Dave Allen, John Carl Buechler and Gabe Bartalos, the latter two of whom had also contributed fine work to From Beyond.

Arrow have not only provided excellent transfers for all five movies; the disks are packed with commentaries, interviews and featurettes, packaged with an 80-page book of new essays and archival material. Hopefully this is just the first volume in a projected series – there’s plenty more to be mined from this vein.

Comments