Crime and Horror from Radiance

I’ve been dipping further into the output of Radiance, yet another company releasing very desirable disks comparable to Indicator (in fact, Radiance seems to ship from the same facility as Indicator). I’ve ordered directly from them once, but have also found a number of releases at the local store where I occasionally trade in disks I’m getting rid of.

The Night of the Devils (Giorgio Ferroni, 1972)

Although Giorgio Ferroni’s career spanned four decades – from 1936 to 1975 – with forty-plus credits, I’d only seen two of his previous films (the sumptuous Gothic Mill of the Stone Women [1960] and the spaghetti western Fort Yuma Gold [1966]) before The Night of the Devils (1972), a collaborative release from Radiance in association with Raro Video. It’s based on Aleksey Tolstoy’s 1839 story The Family of the Vourdalak, previously adapted as the final story in Mario Bava’s anthology Black Sabbath (1963), here updated for a contemporary setting.

Gianni Garko, best known for a long string of westerns – including multiple movies in the Sartana franchise – plays an amnesiac man who wanders across the border into Italy, clothes torn and bloody. At a hospital, doctors run tests and he has disturbing flashes of memory involving violence. A woman named Sdenka (Agostina Belli) turns up and provides some information about his identity. He’s an Italian businessman named Nicola who was driving through Eastern Europe to make a business deal when his car broke down and he sought shelter in her family’s remote farmhouse.

Flashbacks fill in the events leading to his current state. Steeped in superstition, the family lives in fear of a malevolent witch who haunts the nearby forest. They’re waiting uneasily for their father Gorca (Bill Vanders) to return … and anyone who has seen Black Sabbath knows that their fears are justified; Gorca does come back at night, transformed into a vampire who preys on his own family. Nicola tries to save Sdenka, but barely manages to escape with his own life, making it back across the border on foot, deeply traumatized and, it turns out, quite insane. His final face-to-face meeting with Sdenka goes very badly.

More than a decade after Mill of the Stone Women, the violence is more graphic, but Ferroni still emphasizes atmosphere, building a sense of creeping dread as the members of the family fall victim to their own father. With excellent cinematography by Spanish DoP Manuel Berenguer (Narciso Ibáñez Serrador’s The House That Screamed [1969], Gordon Hessler’s Murders in the Rue Morgue [1971]), gloomily picturesque Italian locations, and a very good cast, I’m surprised this movie isn’t better known, but apparently it didn’t get any North American distribution until it was given an official release on Blu-ray from Raro in 2012, now upgraded in this Radiance edition, which is supplemented with a commentary from Alan Jones and Kim Newman, plus almost two hours of archival cast and crew interviews.

*

The Horrible Dr. Hichcock (Riccardo Freda, 1962)

Riccardo Freda had a long career – almost four dozen credits over forty years – which encompassed multiple genres from sword-and-sandal to Gothic to giallo, but he’s been overshadowed by his protégé Mario Bava. It was Freda who was instrumental in easing Bava into directing by walking off both I vampiri (1957) and Caltiki, the Immortal Monster (1959), forcing Bava to step in and finish both movies, on which he had been cinematographer and special effects creator. It was Bava who launched the Italian Gothic boom of the early 1960s with Black Sunday (1960), but it was Freda who contributed perhaps the most perverse movie in that genre with The Horrible Dr. Hichcock (1962).

Unlike Bava’s first masterpiece, Freda’s film is in vibrant colour, echoing Hammer’s recent Gothic movies, a connection reinforced by the setting in Victorian London. Busy British character actor Robert Flemyng, familiar from countless roles as military men and bureaucrats, is renowned surgeon Professor Bernard Hichcock, whose respectability conceals a disturbing secret. Returning home from an operation, he has his wife Margaretha (Maria Teresa Vianello) quickly hustle her guests out of the house so she can join him in the bedroom where he injects her with his experimental anaesthetic. As she lies inert and unresponsive, he enjoys some simulated necrophilia. We realize that the shadowy figure we saw in the prologue knocking out a gravedigger and fondling a young woman’s corpse was actually this upright member of the ruling class.

During one of these sessions with his wife, Hichcock miscalculates and his drug kills her. Grief-stricken, he leaves London only to return years later with new wife Cynthia (Barbara Steele, naturally). Shades of Rebecca as Cynthia feels the oppressive presence of Margaretha everywhere in the house and even sees a ghostly figure drifting through the garden at night. She also comes to suspect that Hichcock isn’t as upright as he ought to be, her nights disturbed by things she can’t quite remember. Her suspicion that he may be trying to kill her is gradually revealed as something more distasteful and she turns to her husband’s assistant, Dr. Kurt Lowe (Silvano Tranquilli) for comfort. Dr. Lowe himself already has suspicions, having discovered Hichcock fondling a fresh corpse in the morgue.

Necrophilia is a subject rarely touched on except in more extreme exploitation movies (Joe D’Amato’s Beyond the Darkness [1979]) or transgressive art (Jörg Buttgereit’s Nekromantik [1988] and its sequel [1991]), so it’s rare to find it in a mainstream film with a respectable cast (perhaps the only other notable example is Lynne Stopkewich’s Kissed [1996], which adds the twist of its necrophile being a woman with deeply romantic rather than sexual feelings for the dead). It’s said that when he realized what he was involved with, Flemyng tried to back out of his contract and, when that failed, tried to ruin scenes so that the movie would be unreleasable, though those kinds of stories always seem a bit dubious to me – did he sign on without having read the script? As it is, he gives a fine performance as the upper class pervert.

Although the subject is not one usually raised in polite company, Freda treats it quite straightforwardly as an interesting study in pathology and the harm an individual’s obsession can cause to those he’s willing to use for his own personal gratification. Sumptuously designed by Franco Fumagalli (hilariously anglicized as Frank Smokecocks in the credits) and shot by Raffaele Masciocchi, The Horrible Dr. Hichcock has an authentic Gothic atmosphere, drawing on the overheated mix of romanticism and perversity at the heart of works like Matthew Gregory Lewis’s 1796 novel The Monk.

Radiance’s edition includes three versions across two Blu-rays – the original Italian, the English-language international (essentially the same cut with English titles) and the shorter, re-edited U.S. version. There are two commentaries, an interview with scriptwriter Ernesto Gastaldi, a visual essay on the Bluebeard theme in movies, and a featurette about necrophilia and the Gothic.

*

Scream and Scream Again (Gordon Hessler, 1970)

I’ve mentioned Gordon Hessler’s Scream and Scream Again (1970) before – eight years ago, when it was first released on Blu-ray by Twilight Time – and was happy to revisit it in this new edition, which features an excellent transfer of both the British and (slightly different) U.S. cuts, a new commentary, new and archival cast and crew interviews, an appreciation by horror author Ramsay Campbell and a condensed 8mm home viewing version.

I’ve always liked this movie for its unconventional qualities, but each time I see it I feel that what is generally seen as messy and incoherent is actually much more carefully conceived than it’s given credit for. Certainly it violates a lot of conventional rules, but it’s not out of control – it’s probably the closest Amicus ever came to an experimental, avant garde feature. What initially appears to be a thrown together collection of random narrative elements all coalesce by the end into a fully comprehensible paranoid thriller with sci-fi overtones. Which is not to say that viewers won’t feel tricked and cheated by the prominent casting of Peter Cushing, Christopher Lee and Vincent Price only to discover that these three genre stars connect only tangentially in the narrative (with Cushing getting just one brief scene). Perhaps audiences and critics would have been more open to the movie’s unconventional approach if those roles had gone to less familiar actors.

Christopher Wicking’s script, adapted from the novel The Disorientated Man by Peter Saxon (a house pseudonym used by multiple writers for publisher Mayflower Books), is an intricate jigsaw puzzle, with the full picture only coming into focus during the climactic scenes. Under the credits, a man jogs through a pleasant area of London; as the credits end, he suddenly stops, clutches his chest and collapses. When he wakes in a hospital room, he discovers that one of his legs has been amputated; we return to him a number of times as a silently menacing nurse (Uta Levka) checks on him, each visit revealing another limb missing.

Then there’s Konratz (Marshall Jones) who returns from England to a repressive Eastern European country (modelled on East Germany), where he proceeds to eliminate obstacles to his rise through the political ranks – beginning with Major Heinrich Benedek (Cushing) who seems to be a little more humane than the cold-blooded Konratz, who takes pleasure in torturing dissidents before killing them.

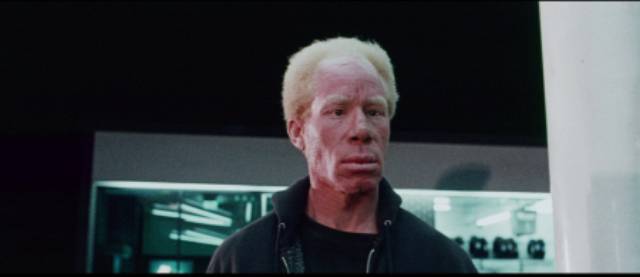

Back in England, Detective Superintendent Bellaver (Alfred Marks) leads the investigation into a series of murders in which the victims (young women) are drained of blood. Using policewoman Helen Bradford (Judy Bloom) as bait, Bellaver finally identifies the probable killer as Keith (Michael Gothard), a man with seemingly superhuman strength. Pursuit leads to the grounds of a mansion which is also a health clinic run by Dr. Browning (Price); cornered in a barn, Keith throws himself into a vat of acid rather than be captured. Browning claims no knowledge of Keith, but one of the earlier victims was an employee of the clinic. And we learn that the silent nurse overseeing the gradual dismemberment of the runner works for Browning.

Meanwhile, in London, Konratz meets with high-level official Fremont (Lee) because the events involving Keith risk exposure of a sinister secret operation. That operation is revealed at last in the film’s final scenes where we discover that Browning is part of an international conspiracy to create a new race of supermen (his experiments requiring fresh body parts, hence the fate of the runner) who are gradually replacing high level officials in various countries around the world – including Konratz and Fremont himself. Keith was an early prototype who malfunctioned, becoming a powerful predator with a taste for blood. Having jeopardized the whole scheme, Browning is discarded and the plan continues.

In the original novel, all of this was part of an alien plot to take over the Earth, but the film keeps it at the level of a vast authoritarian political conspiracy, making Scream and Scream Again one of the earliest, and most unusual, of the paranoid thrillers which proliferated through the early ’70s. Having gradually gained a better reputation over the years, it can be seen now as Hessler’s best movie and the most interesting film Amicus ever produced. The Radiance disk provides it with an excellent showcase.

*

Messiah of Evil (Willard Huyck & Gloria Katz, 1973)

I’ve also written about Willard Huyck and Gloria Katz’s Messiah of Evil (1973) before – in 2011, after watching the movie for the first time on Code Red’s DVD. Made during one of my favourite periods in horror cinema – the boom in low-budget independent movies which also produced John Hancock’s Let’s Scare Jessica to Death (1971), John Hayes’ Grave of the Vampire (1972), Richard Blackburn’s Lemora: A Child’s Tale of the Supernatural (1973), Matt Cimber’s The Witch Who Came From the Sea (1976), among others – when crass exploitation was for a few years superseded by a poetic approach to familiar genre tropes, revitalizing them in unexpected ways.

What all these films have in common is a dream-like quality, the ability to make what had become tired and familiar unsettling again. For the most part, these movies made little or no attempt to rationalize their fantasy elements, giving them an open-ended quality which leaves the viewer uncertain of just what it is they’ve been watching and what exactly it might mean. There are elements of sexuality and madness, with intimations of supernatural horror lurking beneath prosaic surfaces echoing in a more subtle way the cosmic horror of H.P. Lovecraft.

In Messiah of Evil, the narrative remains obscure but what matters is the disturbing atmosphere and striking visuals. Arletty (Marianna Hill) arrives in a small coastal town looking for her artist father; he’s disappeared, but she moves into his beach house – full of his unsettling art – and becomes involved with the decadent Thom (Michael Greer) and his two companions, Laura (Anitra Ford) and Toni (Joy Bang), who move in uninvited. Increasingly strange things occur – both Laura and Toni are attacked by townsfolk who gather in somnambulant groups which erupt into cannibal frenzies. This has something to do with a strange preacher who arrived in the town a hundred years earlier, seeming to bring an infectious evil which is now rising again.

Like other independent horror films – in fact, independent films of all kinds – from around that time, Messiah of Evil seems more influenced by a European sensibility than the Hollywood mainstream. Younger filmmakers were breaking away from the constraints of studio production (and the recently abandoned Production Code) and drawing on other traditions (and film school studies) to explore new ways of telling stories. The late ’60s to the late ’70s remain one of the most exciting and inventive periods in American film and a lot of the work done in that decade remains fresh and exciting.

Radiance have given the film the deluxe treatment, releasing a new 4K scan on a limited edition Blu-ray in a hard slipcase with an 80-page book of essays, a new commentary, a one-hour documentary, a video essay by Kat Ellinger, and a lengthy archival interview with Huyck. A definite upgrade from the Code Red edition, it unfortunately doesn’t carry over the earlier release’s director commentary or two short films by Huyck and Katz.

*

Man on the Roof (Bo Widerberg, 1976)

Bo Widerberg took an unexpected turn after his impressive run of historical films – Elvira Madigan (1967), Ådalen 31 (1969) and The Ballad of Joe Hill (1971) – when he adapted the seventh of Maj Sjöwall and Per Wahlöö’s Martin Beck mysteries, The Abominable Man, as Man on the Roof (1976). The choice of this particular book was in line with Widerberg’s interest in social issues – the story centres around the murder of a policeman and the investigation which exposes a tolerance of brutality and corruption in the force. Low-key and methodical, the film follows the investigation of Beck (Carl-Gustaf Lindstadt) and his colleagues in Stockholm, sifting through evidence, conducting sometimes tense interviews, and unearthing troubling past events which have been suppressed by a system unwilling to examine less savoury aspects of its own behaviour – all leading to an explosive eruption of very public violence.

The opening sequence has Stig Nyman (Hadar Johansson) brutally butchered in a hospital room by an unseen assailant. The fact that he was a cop puts additional pressure on Beck and the homicide department to wrap the case up quickly; however, in looking for a motive, it quickly becomes clear that Nyman was a lousy cop, corrupt and abusive … something that those in charge would prefer not to make public. Beck, a decent man, puts his search for answers ahead of loyalty to the force and develops a begrudging sympathy for the killer as he uncovers the motive – Nyman was responsible for the death of Åke Eriksson’s wife, a diabetic who had been arrested for supposed drunkenness when she needed insulin, locked up by Nyman and left to die in a cell without medical attention.

Ironically, Eriksson (Ingvar Hirdwall) takes his revenge several years later because Nyman is terminally ill and time is running out. A former policeman himself, Eriksson has become so bitter and angry at the force which contained and protected Nyman that, as Beck closes in, he takes to the rooftops and begins to shoot cops on the streets below with a sniper rifle. The quiet, plodding investigation is abruptly transformed into a tense siege, with department higher-ups reacting rashly in their outrage over being attacked, an affront to their sense of authority and righteousness. Beck, feeling some personal responsibility as a member of a very tainted institution, attempts to resolve the situation himself but is abruptly (and shockingly) removed from the story’s resolution by a bullet to the chest.

The entire end sequence – with people scattering as gunfire echoes in the streets, police vehicles pouring into the area and crowds gathering, and helicopters coming in low to spot the sniper – had virtually no precedent in Swedish film at the time. Widerberg was inventing the home-grown action movie, complete with a helicopter being shot down and crashing in a crowded city square. But given his concerns, all this spectacle remains rooted in an examination of institutional corruption and its consequences. This is a much better adaptation of Sjöwall and Wahlöö’s work than Stuart Rosenberg’s The Laughing Policeman (1973), adapted from the fourth book, because the novels used the form of the police procedural to pursue an on-going examination of the state of Swedish society, something Widerberg was fully in tune with, while the American movie severed its story from the social and political roots which fuelled its meaning.

In addition to an excellent transfer (provided by Svensk Filmindustri), the Radiance disk includes a feature-length retrospective documentary, a one-hour documentary about Widerberg from 1977, fifty-minutes worth of selected-scene commentary from genre expert Peter Jilmstad, a brief TV report on the production and a short introduction by Widerberg for a television showing in which he justifies the graphic violence of the opening scene.

*

Big Time Gambling Boss (Kôsaku Yamashita, 1968)

By the late ’60s, the yakuza movie was on the brink of radical change. Soon its tendency towards romanticism would run headlong into a brutal realism which swept away its genre connections to costume dramas about samurai and court intrigues. Writer Kazuo Kasahara played an important role in this new direction; having written traditional gangster movies in the ’60s, he scripted the Battles Without Honor and Humanity series for Kenji Fukasaku, as well as Cops vs Thugs and Yakuza Graveyard, key films in situating organized crime in a contemporary political and economic context.

In 1968, Kasahara wrote Big Time Gambling Boss for director Kôsaku Yamashita, a film which demonstrates clearly the genre ties between samurai and yakuza movies. The story of schemes and betrayals within a clan bound by a code of honour could as easily have been set centuries earlier, but here such rules, once the foundation of society, apply to an outlaw organization which preys on society. That code – which had held powerful sway in Japan up to and through World War Two, until that catastrophic upheaval proved it to be untenable in the modern world – is here shot through with corruption, making those who cling to it vulnerable to schemers who manipulate it for their own ends.

The yakuza world in movies is often seen as self-contained and separate from the larger society, the actions of the characters generally affecting only those within that separate world – women are one exception, preyed on by the gangsters and often dragged into the underworld against their will, most frequently via rape which “spoils” them and makes a normal life no longer possible. Misogyny is endemic to the genre, and yet its central theme is loyalty to the clan and moral conflicts arising from betrayal.

In Big Time Gambling Boss, that theme is explored in depth. It’s the 1930s and the head of the clan lies dying. The governing council gathers to designate a successor. The obvious next in line is Tetsuo Matsuda (Tomisaburô Wakayama), but he still has some time to serve on a prison sentence. The secondary choice is Shinjirô Nakai (Kôji Tsuruta), but he feels unworthy because he was not born into the clan. He urges them to name Matsuda despite his incarceration, but advisor Senda (Nobuo Kaneko) argues for the younger Kôhei Ishido (Hiroshi Nawa). Despite Senda obviously being very shifty, he prevails and the clan begins to fracture. Ishido is weak and manipulable and it gradually becomes clear that he’s being used by Senda for his own purposes – purposes which are ultimately revealed to be betrayal of the clan in a political scheme from which he will personally profit.

As the fractures grow larger, with Matsuda eventually being released from prison to find that control has slipped away from him and his supporters, violence erupts and escalates; Senda’s self-serving plans rip the organization apart and betrayals demand retribution, leading to a blood-bath which destroys the clan – the code of honour itself guarantees destruction; having done what honour demands, Nakai faces what remains of his life in prison. Like the darker samurai films of the ’50s and ’60s, Big Time Gambling Boss reveals traditional Japanese codes of honour to be a self-destructive detriment to society, the film’s classic form belied by the nihilism which would explode just a few years later in the genre revisionism of Fukasaku.

In addition to a fine transfer, the Radiance disk includes two featurettes on the genre and this film’s place within it by experts Mark Schilling (14:36) and Chris D (25:24).

Comments