Monsters, killers and existential dread on Blu-ray

With the end of another year approaching and, as always, more to write about than I have time for, I’ll just mention a few horror movies I’ve recently watched – while half-heartedly contemplating a resolution to put more effort into addressing serious movies next year. Here are four genre movies from the ’70s and ’80s, bracketed by a TV show from 1959 and a Tunisian feature from 2022.

My Bloody Valentine (George Mihalka, 1981)

The explosion of slasher movies in the wake of John Carpenter’s Halloween (1978) coincided with the heyday of the Canadian tax shelter, a program to support production up here by encouraging private investment with low risk. Lasting roughly a decade, the tax shelter produced very mixed results; while it did help to launch some prestigious projects (say, Louis Malle’s Atlantic City [1980]), and provided a solid grounding for some Canadian filmmakers to launch their careers (like David Cronenberg), it also encouraged a lot of cheap productions with little ambition – in fact, commercial failure could be beneficial to investors because their investments would offset their taxes from other businesses. The general impression at the time was of a lot of junk and sleazy exploitation movies masquerading as U.S. productions, with Canadian cities standing in for New York, Chicago and Los Angeles.

This was partly due to an understandable attempt to tap into the U.S. market, partly due to the fact that lower production costs combined with the tax shelter could stretch a small budget much further than anywhere South of the border, thus attracting American investment. Also not surprising was the impulse to imitate successful American movies – we had cheap disaster movies, cheap action movies, and perhaps most abundantly cheap horror movies. In particular, Canada became a fertile site for slashers, mostly masquerading as American productions, though during the genre’s core years it was sturdy enough not to need a full disguise, giving work to Canadian actors and directors.

Many of these movies stuck close to the core formula – prologue long in the past in which some traumatic event triggers madness which returns in the present to prey on a particular group who often deserve some kind of punishment. The pattern quickly became so familiar that the genre had exhausted its audience by the mid-’80s, pushing the boundaries of what was acceptable in terms of graphic violence and increasingly extreme gore to sell tickets. This created a tension between filmmakers and censors (and the MPAA in the U.S.), which often resulted in the much-touted effects being drastically trimmed or eliminated altogether, leaving fans frustrated by bare-bones stories that failed to deliver promised thrills.

But inventive filmmakers occasionally injected something fresh into the formula which might off-set such censorial trims. This is true of my personal favourite slasher, George Mihalka’s My Bloody Valentine (1981). While the movie sticks to the familiar structure, it makes no attempt to conceal its regional Canadian origins and roots its story in a fairly bleak working class milieu, in contrast to the typical middle class, suburban context.

The movie is set in a small, impoverished Maritime mining town – shot on location in Cape Breton, Nova Scotia, which provides an interesting link to Don Shebib’s Canadian classic Goin’ Down the Road (1970). The characters are mostly young people whose options are limited to working underground or, like Joey and Pete in Shebib’s film, heading West for potentially more profitable pastures. In fact, angry protagonist T.J. (Paul Kelman) has recently returned to town from a failed attempt to make it on the West coast. His attempts to restart a relationship with Sarah (Lori Hallier) produce conflicted feelings in her and escalating tension with her current boyfriend Axel (Neil Affleck), an antagonism which takes on class implications as Axel works underground in the mine owned by T.J.’s father.

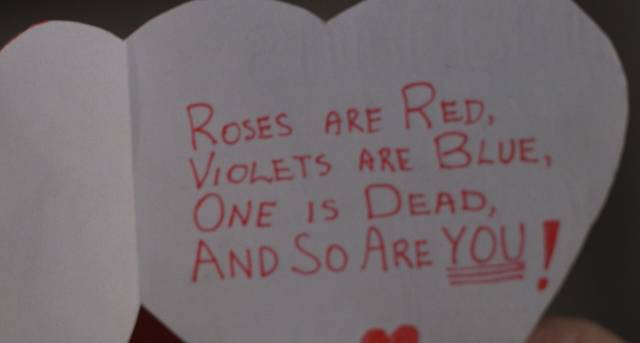

But twenty years before these events, there was a cave-in and miner Harry Warden was left to die. Having survived and dug himself out, he emerged to go on a Valentine’s Day rampage to exact revenge on those who had abandoned him. Today, for the first time in two decades, the town is planning a big Valentine’s Day dance, but the older folk are nervous as they remember what once happened on that day. In the days leading up to the dance, someone begins killing people and sending cut out hearts in candy boxes to warn additional targets.

The mayor and police chief try to keep a lid on the developing situation without publicly revealing that Harry Warden seems to be back. With the dance cancelled, the young folk arrange their own event – unfortunately in a room at the mine. As the party gets underway and people pair off and look for quiet places to make out, a figure wearing miner’s clothes, a hard hat and a breathing mask brutally kills them in gruesomely creative ways. Back when the movie was released, most of the gore was cut out to meet MPAA restrictions, but the well-observed setting and characters managed to limit the censors’ impact and the film remained one of the best examples of the genre.

Although most of the excised effects were restored for a 2009 DVD release, they were of very low quality until Scream Factory did a 4K restoration of the movie in 2020, now reissued as an extras-packed three-disk, dual-format 4K/Blu-ray edition which includes both the original, compromised theatrical cut and the (mostly) restored complete version which adds considerable impact with the more graphic killing scenes. With its solid script by John Beaird (who also worked on the same year’s Happy Birthday to Me and William Fruet’s 1982 Deliverance clone Killer Instinct), strong direction by Mihalka and a fine cast, My Bloody Valentine remains one of the best, most effective horror movies of its period, and one of the most notable products of the tax shelter years.

*

Cujo (Lewis Teague, 1983)

I’ve been a Stephen King fan for almost fifty years, ever since reading Carrie in paperback in 1975 and almost immediately finding a copy of the ‘Salem’s Lot hardcover at the now very long-gone Galaxy Books on Donald Street here in Winnipeg (where I also bought first edition hardcovers of The Shining and The Stand). I consider myself lucky to have read ‘Salem’s Lot before it received any publicity, because nothing about the packaging gave away the big reveal – I think it was around a hundred pages in when it slowly dawned on me that this was a vampire story; that experience would be impossible for anyone coming to the book when it became a bestselling paperback because the cover bore a pair of embossed, blood-dripping fangs. I bought everything he published, sometimes disappointed, sometimes thrilled – until the mid-’90s when he faltered badly with duds like Insomnia, Desperation and The Regulators. I kept buying, but some books I just didn’t get into (the last three volumes of The Dark Tower, Rose Madder, Lissey’s Story). I never quite gave up, but my feeling of attachment faltered … until Under the Dome, which launched an impressively sustained third act, not always fully successful, but never sinking again to the nadir of Insomnia. Now in his mid-70s, this year King published one of his best novels in Holly.

All of which is by way of providing a bit of context for Cujo, published in 1981 and adapted as a medium-budget movie in 1983, the fifth feature of Lewis Teague, a minor figure held in high regard by genre fans for directing Alligator (1980) from a terrific John Sayles script. The novel is a modest chamber piece compared to those which had preceded it – King had launched his career with encyclopedic treatments of vampires, ghosts and apocalyptic plagues, scaling back a bit with a couple of paranormal thrillers (The Dead Zone, Firestarter) which expanded on what he had started with Carrie. Cujo is essentially a two-character story set in a single, small, confined space, a psychological pressure cooker which spirals down into a very dark place (a place revisited by King two years later in Pet Sematary, which also revolves around the traumatic death of a child).

This modest, tightly contained conception may explain why Cujo lent itself more readily to adaptation than most of King’s other books, which have so often faltered as movies. After a lyrical opening with Cujo, a St. Bernard, chasing a rabbit in a sun-dappled meadow, which abruptly ends as the dog gets bitten by a rabid bat, we’re introduced to the Trenton family – Donna (Dee Wallace), Vic (Daniel Hugh Kelly) and young Tad (Danny Pintauro) – a seemingly happy middle-class group living in a small New England town. But there are tensions beneath the idyllic surface which become apparent very quickly. Advertising man Vic is facing a catastrophic business failure; Donna is filled with guilt over an affair with Steve Kemp (Christopher Stone), a local man who gets very stalker-y when she tries to break it off.

And then there’s the car. Donna drives a beat-up Ford Pinto with an unreliable engine. A local recommends Joe Camber (Ed Lauter) as a good, cheap mechanic and the unpleasantly cranky guy agrees to work on the Pinto. Unfortunately, Cujo is Joe’s dog and by the time Donna and Tad arrive at the remote farm, Joe is dead. Finding no one at the farm, Donna is suddenly attacked by the mad dog, barely making it back into the car. Of course, the engine dies and she and Tad are trapped. With Vic away in the city to deal with his business crisis, no one knows where Donna and Tad are and they have no way to call for help because the big dog is lurking nearby, desperate to attack.

And that’s it – mother and son suffer from heat, hunger and thirst, unable to do anything. In the book, by the time rescue arrives it’s too late for Tad and Donna has been bitten. Although she’s successfully treated for rabies, things look bleak for her and Vic. It’s pretty nihilistic, not to say sadistic – by implication, she and Tad are punished for her transgression with Kemp. The film pulls back from the abyss, sparing Tad. Other than Camber, only peripheral characters are killed by Cujo and the final image suggests that the family unit has survived and come back together. I find that a little hard to swallow – I kept thinking what a total asshole Vic is, buying himself a Porsche but forcing Donna to cope with a broken-down old beater, though he could obviously afford something better. No wonder she had an affair, though it’s too bad she did it with another chauvinist asshole.

As a creative exercise – how to build and maintain tension with two characters trapped in a small car without becoming boring and repetitive – Cujo is quite successful, but in the end it feels a bit like torture porn, an excuse to make Dee Wallace and Danny Pintauro suffer for our entertainment. In this, it’s one of the most faithful King adaptations – except for that last minute salvation and the elimination of the book’s suggestion that there’s a supernatural element to Cujo’s infection – but despite Jan de Bont’s fine cinematography and a very good cast, it remains a minor work, efficiently directed by Teague, but not particularly memorable.

Kino Lorber’s Blu-ray presents a 4K scan from the original negative and a stack of extras.

*

Creature From Black Lake (Joy Houck Jr, 1976)

For some reason, Bigfoot was a big thing in the ’70s, no doubt due to the notoriety of the Patterson-Gimlin home movie shot in Northern California in 1967, purporting to record a sighting of the elusive cryptid. Although not the first to jump on the bandwagon, the most successfully marketed movie at the time was Charles B. Pierce’s The Legend of Boggy Creek (1972), a “docudrama” about sightings in Arkansas in the 1940s. Pierce aimed to present the story as an exploration of local folklore hinting at natural mysteries, inevitably leaning towards fear of the unknown. Others went straight for exploitative horror, most notoriously Michael Findlay with Shriek of the Mutilated just two years later. Findlay’s lead was followed by James C. Wasson with Night of the Demon (1980), but director Joy N. Houck Jr. and writer-producer Jim McCullough Jr. leaned more towards Pierce’s approach, though they ditched the pseudo-documentary element and drew on ’50s monster movies – as suggested by the title of Creature From Black Lake (1976).

The movie opens with an effective scene: two old-timers out fishing are being watched from the shore by a shadowy humanoid figure. Moments later, a hairy hand reaches out of the water and pulls one of the men under. The other becomes a bit of a pariah in the community because no one wants to acknowledge the existence of the creature. Meanwhile, a college class hears from a prof about the legends of Bigfoot and two of his students decide to do a term project on the myth and the possible reality behind it.

The casting of veteran character actors Jack Elam and Dub Taylor as a couple of jittery locals who have encountered the creature adds some flavour, but the leads end up being pretty irritating. As the students, John David Carson and Dennis Fimple are clumsy and kind of stupid; they enter a small rural community and behave like horny frat boys, annoying almost everyone they meet instead of carefully digging into the local lore. Otherwise the movie follows the usual path of mysterious encounters, intimations of creature violence and the lack of a clear resolution – nature retains its mysteries.

What’s most notable about Creature From Black Lake is the excellent widescreen photography by Dean Cundey, just a few years into a long career which began with exploitation and blaxploitation movies and ramped up in the late ’70s when he connected with John Carpenter (from Halloween [1978] to Big Trouble in Little China [1986]). Here, he provides some beautiful landscape imagery which gives the movie a sense of scale and atmosphere which raises it above typical low-budget regional exploitation, impressively mastered on the Synapse Blu-ray from a 4K scan of the original negative.

The disk includes an interview with Cundey about his early career and a commentary from Michael Gingold and Chris Poggiali.

*

Godmonster of Indian Flats (Fredric C. Hobbs, 1973)

Though it lacks the polish of Creature From Black Lake, I enjoyed Fredric C. Hobbs’s Godmonster of Indian Flats (1973) more, partly because it strays further from familiar genre tropes and particularly because of its demented monster design. This is what I look for in low-budget regional movies, a strange mix of elements which may not gel completely but offer unexpected tangents that keep things interesting.

Up first is sheep farmer Eddie (Richard Marion) who takes a break in Reno to try his luck at the casino. He wins a little, which attracts the attention of some crooks who steal his winnings. Coming across these thieves later in a bar, he causes a scene and gets himself kicked out of town by the cops. Feeling bitter, he beds down in the sheep pen and has a weird experience – is it a dream? a hallucination? or perhaps an alien visitation? There are strange lights and noises, and when he wakes the next day there’s an odd organic object in the straw beside him.

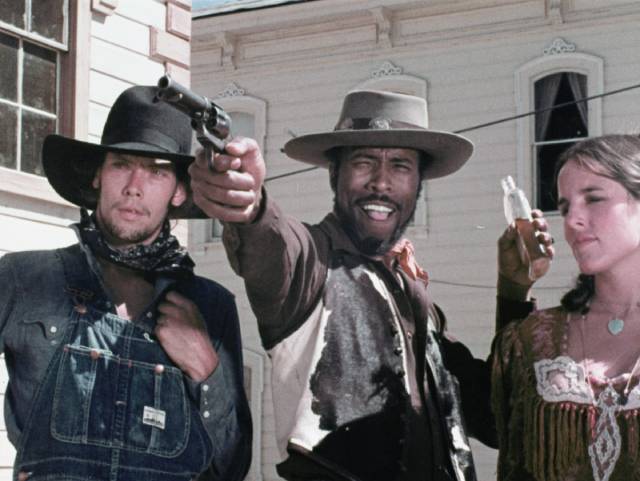

Meanwhile, in town corporate guy Barnstable (Christopher Brooks) arrives with a proposal to buy up all the mining rights in the area, even though the local silver deposits are supposedly exhausted. Mayor Charles Silverdale (Stuart Lancaster), the local patriarch, doesn’t cotton to this interloper, resentment of city slicker ways blending with racism as Barnstable is Black. Tensions escalate during the town festival, with drunks doing target practice in the street. Barnstable himself drinks too much and decides to show off with a bit of shooting of his own. A well-trained dog feigns being shot and everyone turns on Barnstable as an elaborate dog funeral is staged.

But wait … there’s also Professor Clemens (E. Kerrigan Prescott) who has a research lab in an abandoned industrial building just outside town. He comes across Eddie and the thing in his sheep pen and takes it back to the lab for study. It turns out to be a strange embryonic sac and before long hatches out a large mutant sheep-monster, which Clemens keeps in a glass incubator as he pokes and prods it. And then in the final act, the creature breaks out of the lab and rambles around on its hind legs – perhaps inadvertently suggesting that Eddie may have impregnated one of his own sheep – scaring children and damaging property. The Godmonster is a wonder of low-budget design, a shaggy sheep-headed humanoid, vaguely reminiscent of the mutant bear in John Frankenheimer’s Prophecy (1979).

Woven together, the various narrative strands of Hobbs’s movie suggest a strange, somewhat impoverished alternate reality which has its own kind of sense different from ours. Movies like this typically get low ratings on IMDb and elicit contempt from viewers well-trained in what to expect from the commercial mainstream … but I love its demented invention, not to mention seeing Stuart Lancaster, the desert patriarch of Russ Meyer’s Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill! (1965), gleefully chewing the scenery once again.

As is typical of Something Weird/AGFA releases, the Blu-ray is loaded with fun extras, including Harry Winer’s The Legend of Bigfoot (1975), a low-rent “documentary” which is mostly a travelogue/nature movie shot in the Pacific Northwest into which is grafted some dubious footage showing Bigfoot – the missing link? – running around in the woods while professional tracker Ivan Marx and his wife Peggy talk very seriously about the elusive creature and the natural mysteries it represents.

There’s also a half-hour “documentary” about people’s experiences with UFOs and a public service movie about how to deal with school bus fires.

*

Ashkal (Youssef Chebbi, 2022)

Back in the Spring, I saw the first Tunisian horror film I’d ever come across, Abdelhamid Bouchnak’s Dachra (2018), about which I had some reservations. I didn’t expect to see another just six or so months later, but here’s Youssef Chebbi’s Ashkal: The Tunisian Investigation (2022). It’s difficult when encountering something unfamiliar not to look for parallels to help orient oneself, so I’ll just say that this mystery with supernatural overtones reminded me a little of Kiyoshi Kurosawa, particularly Pulse (2001) and Cure (1997). Rooted in Tunisian politics and the turmoil which ran through multiple North African countries in the first decade of the century, the film blends material politics with metaphysics and I admit that my scant knowledge of the narrative background no doubt means I missed a certain amount of what Chebbi was saying. But that didn’t keep me from appreciating the story which is foregrounded in the film.

Much of the narrative centres on a vast, unfinished development on the outskirts of Tunis called the Gardens of Carthage, a sprawling complex of concrete shells abandoned during the political turmoil of 2010. The film opens with the camera exploring these structures in twilight, eventually coming upon flames and swirling smoke. Police arrive to discover the charred body of a night watchman, initiating an investigation in which intense officer Fatma (Fatma Oussaifi) and her stolid older partner Batal (Mohamed Grayaâ) run up against resistance from their superiors who smell something potentially revolutionary in this death and subsequent similar deaths, which seem to be linked to a mysterious hooded figure who may be inspiring individuals to self-immolate as some form of as-yet undefined protest.

It seems somewhat radical to place a woman, particularly one who aggressively bucks the system, at the centre of the story – Fatma’s pursuit of the puzzling investigation rubs her colleagues the wrong way and she gradually finds herself ostracized and eventually betrayed by Balal, who is unwilling to risk his own security by stirring up politically troubling questions. But those questions take on more nebulous implications as the mysterious figure seen at the scenes of the fiery deaths assumes supernatural qualities. Perhaps it is the spirit of the thwarted revolution refusing to be repressed, drawing more and more people into self-destructive acts of opposition to the authorities who have clamped down on the people’s desire for a more open and democratic society.

Haunting, mysterious and unsettling, Ashkal is beautifully composed with a cool visual formalism that gradually cracks from the pressure of repressed energies which threaten to consume the characters. Whatever the metaphoric implications of the narrative, the film moves inexorably towards an open-ended apocalyptic vision, challenging the illusion of control which the authorities struggle to maintain. In this, it also reminds me a little of Jayro Bustamante’s La llorona (2019), another film which addresses deep political wounds via a subtle supernatural narrative.

To help those unfamiliar with the political background, Yellow Veil’s Blu-Ray includes a half-hour Q&A with director Chebbi and star Oussaifi following a screening at Lincoln Centre, a brief featurette about the Gardens of Carthage, and a booklet essay by Tyler Wilson. There’s also an alternate ending, which amounts to a brief unnecessary extension to the finished film’s haunting final shot.

*

World of Giants (Various, 1959)

Although a number of very familiar names were involved, I had never heard of World of Giants (1959) before I saw an announcement about an upcoming release from ClassicFlix. I couldn’t resist, and immediately ordered the Blu-ray. This thirteen-part series boasts a who’s who of ’50s and ’60s film and television writers and directors, with nine episodes produced by William Alland, among whose feature credits are It Came from Outer Space (1953), Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954) and its sequels, This Island Earth and Tarantula (both 1955), The Space Children and The Colossus of New York (both 1958). Considering his previous work, it isn’t surprising to find episodes of the show directed by former collaborators Jack Arnold, Eugène Lourié and Nathan Juran, along with Byron Haskin. Assigning these accomplished theatrical filmmakers to a half-hour sci-fi action series makes sense given the show’s ambitious (if silly) concept.

Marshall Thompson, star of Fiend Without a Face, It! The Terror from Beyond Space (both 1958) and First Man into Space (1959), plays agent Mel Hunter who, while on a mission behind the Iron Curtain, was caught in an explosion of experimental rocket fuel. Before you can say “Scott Carey”, he’s shrunk down to six inches. Far from being a career-ending handicap, this just makes him more valuable than ever. Teamed up with friend and fellow agent Bill Winters (Arthur Franz), Mel travels around in a specially outfitted briefcase, strapped into a miniature pilot’s seat as Bill sneaks him into enemy lairs where he can suss out evil Commie plots while occasionally fighting off menacing giant cats and dogs.

Given the brief running times, stories remain very rudimentary, with Mel addressing the audience directly to comment on his situation. But what it lacks in nuanced drama, World of Giants makes up with some quite impressive special effects. It’s surprising how deftly the TV crew execute the kind of effects used by Jack Arnold and his team just two years earlier on The Incredible Shrinking Man (1957). With Thompson performing among oversized props, he’s composited seamlessly into the live action full-size sets, chatting with Franz, their bosses and, after the first few episodes, Marcia Henderson, who plays nurse Dorothy Brown who juggles her duties monitoring the little guy’s health and a tentative romance with Bill. There’s almost a sit-com feel with the odd couple agents sparring with the attractive woman who occasionally comes between them.

The limitations of the short, episodic form quickly make the show seem repetitive and I imagine production costs were relatively high because of the volume of effects work, so it’s not surprising that it only lasted thirteen episodes. Still, its visual accomplishment is impressive. Among the writers were Meyer Dolinsky and Robert C. Dennis, both of whom went on to write scripts for The Outer Limits (1963-65), the former also writing an episode of Star Trek (1966-69), many episodes of which were produced by Fred Freiberger, who scripted one episode of World of Giants.

Scanned from 16mm prints, the show looks surprisingly good on Blu-ray, though there are signs of damage (scratches, missing frames) and the usual issues with old-school photochemical compositing are there – some matte lines, shifts in grain and contrast – but overall, World of Giants is an enjoyable rediscovery and an amusing footnote to the miniature people sub-genre which runs from Tod Browning’s The Devil-Doll (1936), through Jack Arnold’s The Incredible Shrinking Man and Irwin Allen’s Land of the Giants series (1968-70), and on to Honey, I Shrunk the Kids (1989) and the like.

Comments