Movies and reality intersect in two recent releases

I developed my love of movies early. Trips to a theatre were always a significant outing when I lived in a small English village and we had to make a trip to the big town which took about half an hour by bus, a little less by car. We’d take sandwiches and snacks and buy ice cream from the ushers during breaks in the show. I still have vivid memories of seeing Talos, the bronze giant in The 7th Voyage of Sinbad, the skeleton fight in Jason and the Argonauts and the insect-like lunar inhabitants of First Men in the Moon. There was the Nautilus crashing through big sailing ships in 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, the giant crab boiling in a hot spring in Mysterious Island, the attack on Rourke’s Drift in Zulu … The colourful spectacle of movies fired my imagination and was reinforced by what I saw on our small black-and-white television at home – only two channels back then, with limited air time; I can still remember sitting by an open fire in the living room and watching King Kong and Quatermass II.

When we moved to Canada, I was old enough to take a bus into St. John’s with my friend Don to go to one of the three movie theatres – sitting on a Saturday afternoon through a triple bill of the first three James Bond movies (which were barred to me in England as they were rated for adults only); or The Longest Day, 2001: A Space Odyssey, Planet of the Apes and Frankenstein Meets the Space Monster. By the beginning of the 1970s, the nature of the spectacle was changing, as was my relationship to it – I can recall the impact of Easy Rider and, more potent, Straw Dogs and The Devils. By the time I was in my mid-teens, I was no longer a childishly naive viewer – I was coming to understand how movies were made, how they worked, how filmmakers crafted narrative and guided our emotional responses to the images they created.

By the time I arrived in Winnipeg in 1973, and suddenly had what seemed like unlimited access to dozens of movies every week, I would immerse myself in the experience, sometimes seeing two or three movies in a day, emerging from the theatre and feeling that the world outside had somehow been transformed – I would scan my surroundings as if my eyes had become cameras, panning and tilting to create a constantly shifting perspective which offered the promise of some imminent revelation… But of course, the real world just kept going on its way as usual, vaguely disappointing because it never coalesced into a compelling narrative.

So between movies I would daydream and invent stories for myself; I was very young when I wrote my first short stories, was writing what were supposed to be film scripts in late adolescence – banged out my first novel when I was seventeen. The act of inventing stories imbued my daily life with some of the thrill I felt when sitting in the dark watching a movie. Reality seldom matched that feeling. (Over a couple of decades, I wrote dozens of short stories, maybe ten novels, a bunch of scripts – all unsold and unproduced, because I wasn’t a “serious” or disciplined writer; it was the initial act of invention which produced the thrill, but I was seldom interested in the hard work of rewriting which was obviously a necessity if any of this work was to be whipped into professional shape.)

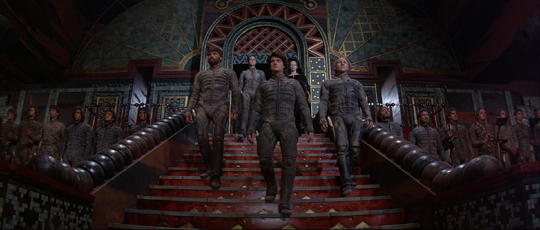

The passion for watching movies was always there and, perhaps inevitably, stretches of my working life have skimmed the fringes of filmmaking, and for one fifteen year stretch I became a professional. My first job in Winnipeg when I was eighteen was a summer training position with a small company that made commercials and industrial films; when I went back to school in my early twenties, I became a reviewer for the student paper, which got me free passes to a lot of new releases; that writing experience led unexpectedly to my encounter with David Lynch when I was commissioned to write about the making of Eraserhead, and that in turn led to my six months in Mexico working on Dune. But that didn’t take me further – partly, no doubt, because of the same lack of commitment and follow-through which made my fiction-writing a dead end.

And yet, the lingering taste left by my Dune experience no doubt played a part in me joining the Winnipeg Film Group, where I made a few short films and began to work on other people’s movies; that was when I discovered a love of, and affinity for, editing – ironically, the area which that job with Western Films back in 1973 had supposedly been training me for. If that had worked out and I had really applied myself, would I have had a long career in production? That’s a path impossible to imagine now. But two decades later, I found myself making a living as an editor of documentaries, and occasional dramas, teaching editing workshops and passing along my own enthusiasm for what has always remained my favourite part of the filmmaking process.

But that career eventually wound down – partly through changes in the industry here in Winnipeg, partly no doubt due to my own innate, self-defeating tendencies, and my connection to movies was once again primarily as a viewer, though by that time my occasional writing for various periodicals had morphed into regular posts about film here on my website. Through it all, movies have remained a central aspect of my intellectual and emotional life, though that relationship has undergone many changes, most significantly in the shift from going out to movies to mostly experiencing them at home through my ever-expanding collection on disk.

But what I’ve gained in convenience and selection, I’ve lost in something less tangible; the sense of occasion which went with the effort of getting out, going to a theatre, buying a ticket and sitting in anticipation before the lights dimmed and the chosen movie began to roll. Now I sift through the pile, find something that suits my mood and slip it into the player. I still get enormous enjoyment out of watching a good movie (sometimes even a not particularly good movie), but easy access and too-easy distractions in my living room inevitably threaten the feeling of engagement – to some degree, watching movies has become too much of a habit and there are times, perhaps too frequent, when I realize I’ve barely been paying attention to what’s playing on screen. I hate when that happens, but it’s something I don’t seem to have any real control over.

Which is why I’m always excited to find myself watching something which engages me fully, drawing me into the movie’s imaginative space in a way which reminds me of what it used to be like when I was an obsessive theatre-goer. It happens that I recently recaptured that experience with two very different movies, neither of which I’d seen previously … in fact I’d never even heard of them until they appeared on disk and attracted my attention.

*

Closed Circuit (Giuliano Montaldo, 1978)

These rather long-winded reminiscences have been triggered by watching Giuliano Montaldo’s Closed Circuit (1978), a film paradoxically made for television by the eclectic director of diverse features like the classic heist movie Grand Slam (1967) and the searing Sacco and Vanzetti (1971), based on a glaring case of historical injustice. The history of cinema is full of self-referential films about filmmaking, but there have also been movies which touch on the experience of movie watching – Anthony Asquith has a wonderful, lengthy sequence set in a theatre in A Cottage On Dartmoor (1930) which focuses entirely on the faces of the audience as they watch a movie we don’t see; Terence Davies does something similar in The Long Day Closes (1992), reflecting his own experience of being transported out of his own troubled childhood by immersing himself in this other imaginative space.

In Closed Circuit, as in movies as disparate as Buster Keaton’s Sherlock Jr. (1924), Woody Allen’s The Purple Rose of Cairo (1985) and Lamberto Bava’s Demons (1985), the barrier formed by the screen between the audience and the imaginative space of the movie becomes permeable, reality and illusion entangled in ways which illuminate our relationship with the images and narratives projected onto that screen. It’s impossible to say much about Montaldo’s film without revealing spoilers, so be warned.

One afternoon, a random group of people gather at a fairly nondescript neighbourhood theatre which is playing a spaghetti western (although there are prominent posters for Tonino Valerii’s Day of Anger [1967], the movie on screen is Giulio Petroni’s A Sky Full of Stars for a Roof [1968], both of which starred Giuliano Gemma). The theatre lobby and office are full of posters which draw the eye of a movie fan, from Jeff Lieberman’s Squirm (1976) to Francesco Barilli’s The Perfume of the Lady in Black (1974) – this is apparently a small repertory theatre catering to movie buffs, people who come prepared to engage with what they’re watching on a deep psychological and emotional level.

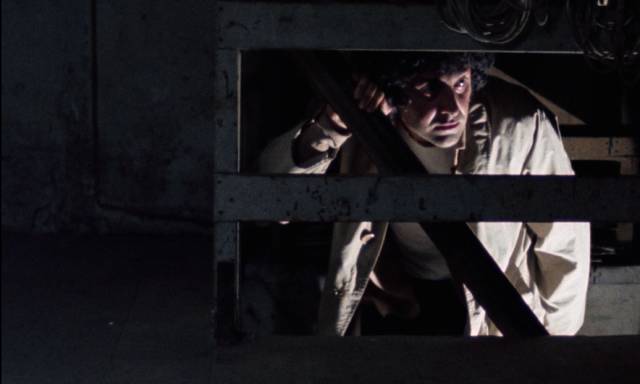

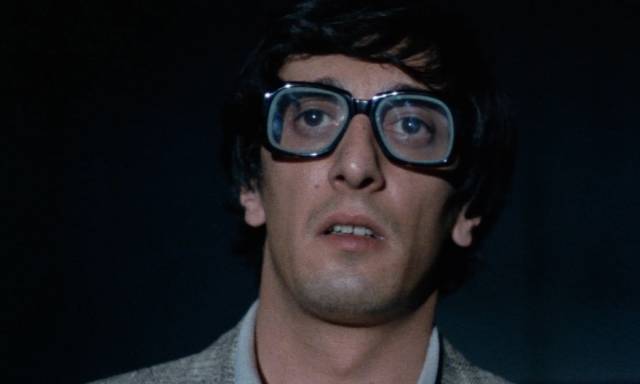

Although the members of the staff and audience remain unnamed, we recognize them as types and attribute certain characteristics to them – a couple of teens more interested in necking than watching; a cantankerous older woman and her irritable companion, perhaps a granddaughter or caretaker; a middle-class couple obviously here for a clandestine meeting; a couple of shady guys, temporarily hiding in the dark; a gay man who lingers at the entrance to the washroom at the side of the auditorium, hoping to engage with any one of a number of young men in the audience; a neurotic young man irritated by other audience members who distract him from engaging with the movie; an odd, twitchy man who seems more interested in the audience than the film, jotting notes in a large notebook.

Partway through the movie, an older man enters and does what really annoys anyone who’s been to a lot of movies; despite there being many empty seats, he sits down beside the teenage couple and right in front of the neurotic young man, whose view he blocks, forcing him to move. We later learn that he is a retired civil servant with a passion for movies, going two or three times a day; for him those flickering images are more real than reality (a feeling I can identify with!).

The movie reaches its climax, a classic western showdown in a barren landscape. Gemma and William Berger face off, the moment drawn out as the camera cuts ever closer, leading to those familiar screen-filling eyes as the two men gauge one another and prepare to draw. The tension stretches to breaking point … Gemma draws and shoots … and the retired civil servant slumps against the teenage girl … she screams and we see blood spreading over his shirt above his heart.

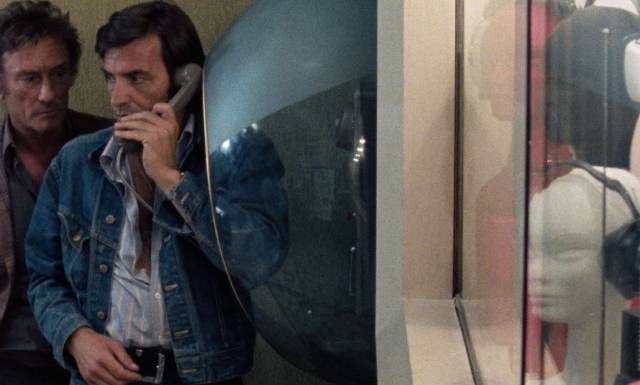

Quick-thinking staff lock the doors, preventing anyone from leaving before the police arrive and the film becomes, for a while, a police procedural. Everyone must be interrogated as the investigators try to find a motive. They set up a desk on the cluttered stage behind the screen and Montaldo creates a wonderful, almost throwaway image as the stage lights render the screen transparent and from the auditorium the questioning of audience members looks like a movie playing on the screen, further blurring the difference between “real” and “imaginary”.

Baffled, with no apparent motive and no clear idea of how the crime was committed, the officer in charge decides to re-stage the event; everyone has to return to their original places and do exactly what they did before, with the theatre’s ticket-taker assuming the role of the victim. The movie plays on screen, the final showdown arrives … the fatal shot is fired by Gamma … and the ticket-taker slumps against the girl, who screams again. Just like a movie, actions unfold according to a predetermined pattern.

The odd man with the notebook approaches the police with a theory, but they quickly dismiss him as a crank. He’s a sociologist with an interest in the way an audience interacts with the movie. But his esoteric theorizing is of no interest to men dealing with an obviously material crime. Yet he’s the one who, climbing a ladder, finds a bullet hole high in the screen, suggesting that the killer was up on a catwalk, somehow unseen by the police stationed behind the screen during the reenactment.

Although it’s clear from the reenactment that none of the staff or audience can be the killer, the police still refuse to allow anyone to leave and it becomes apparent that Closed Circuit is more Bunuel’s The Exterminating Angel than Bava’s Demons … everyone is caught in a strange experiential loop, the audience themselves now characters in a movie. Several people form a committee with demands – food and toothbrushes – while a crowd has gathered outside and television crews report on the strange events in the theatre, reports which those inside watch on TVs brought in to keep them distracted (and feed their insatiable need for images and stories).

With the reputation of the police suffering, the commissioner arrives to take charge, insisting on yet another reenactment against the advice of the investigating officer. With no one else willing to take the risk, the commissioner himself sits in the victims’ seat. The movie once again unfolds on screen and the commissioner’s bluster becomes increasingly forced; he grows more nervous as the climactic showdown approaches, squirming in his seat, and finally as the camera closes in on Gemma’s eyes, he abruptly stands up and starts backing towards the exit. Up on screen, Gemma forgets about his opponent and stares down at the commissioner, his gun tracking the man’s attempts to dodge what is now obviously coming. As the commissioner turns and bolts towards the door, Gemma shoots him in the back.

As everyone files out of the theatre, with the authorities unsure of how to explain what has happened over the past few days, the sociologist finally gets to explain his theory to the investigating officer. The mystery here is metaphysical rather than material, rooted in that deep emotional engagement we have with movies, experiencing the images as a form of reality which, as we watch, supersedes our actual reality, becoming more real than real. He references Ray Bradbury’s famous short story The Veldt (from his collection The Illustrated Man, filmed by Jack Smight in 1969), in which television of the future becomes so immersive that characters enter the screen and roam in the world depicted, falling victim to the dangers which inhabit that world. It’s significant that the events in the theatre are triggered by the retired civil servant, a man who has given himself almost completely over to the imaginative space of the movies – he’s not a casual customer at the matinee, but rather someone who lives for the vicarious experience offered by the images on screen … and on this particular day, dies in that experience.

Closed Circuit is a subtle and playful examination of this intricate connection between audience and image, full of details which draw the viewer in, both visual (through Montaldo’s supple and expressive use of a mobile camera) and behavioural (through the lively performances of a talented cast fully engaging with the material). Made on a small budget for Italian television, the film captures the flavour of my own life-long experience of watching the movies (though luckily I’ve avoided fatal encounters!).

The movie has been resurrected by Severin, who thankfully had access to film elements rather than a broadcast tape master – disk producer Kier-La Janisse goes into the long, difficult process of obtaining the rights and creating the new master in an introduction which expresses her enthusiasm for the film. There’s an interview with Montaldo, who died at 93 just months before the disk’s release, in which he talks about his television work, how this project came about, finding a suitable theatre in which to shoot, and getting the large cast to work for almost no money. There’s also an appreciation by Kat Ellinger of character actor Flavio Bucci, who plays the oddball sociologist; he had a long, varied career and a wild personal life. Though not the most elaborate Black Friday release of 2023 from Severin, Closed Circuit is the one I personally connected with most.

*

Charlie Victor Romeo (Robert Berger, Patrick Daniels, Karlyn Michelson, 2013)

There’s no connection at all between Montaldo’s meta-movie and Charlie Victor Romeo (2013), but this – what? staged documentary? – is immersive in a deeply troubling way. Audacious in conception and deceptively simple in execution, it’s essentially a filmed stage play, minimalist and focused only on the essentials of its chosen subject. That subject is the sometimes devastating intersection between technocratic efficiency and contingency.

First presented on stage in 1999, Charlie Victor Romeo is based solely on transcripts from cockpit voice recorders (the devices referenced by the title acronym) from six air disasters which occurred between 1985 and 1996. The set suggests a cockpit seen from the front (a slightly more sophisticated approximation than, say, the plane in Ed Wood’s Plan 9 from Outer Space), and the handful of actors appear in various roles – pilot, co-pilot, flight attendant, air traffic controller – the shifting of familiar faces through the different positions adding a strangely ritualistic quality to the six scenes; despite specific technical differences, these incidents gradually form a pattern which illuminates the film’s central theme, which is the limitations of professionalism and expertise in the face of unexpected and uncontrollable events.

Limited to the transcripts, the “drama” is stripped of character and “plot” … the dialogue is often dense and technical, the spoken short-hand of trained personnel immersed in the job. One of the many chilling aspects of the film is this maintenance of seemingly cool professionalism in the face of what quickly becomes clear is imminent death. What is left to the viewer’s imagination is the unseen cabin full of passengers who have no idea of what is happening in the cockpit. Watching the film makes the prospect of flying again rather daunting. While crashes remain relatively rare when seen in the context of how many flights there are, seeing how quickly things can go wrong and how devastating errors can be shatters any sense of complacency familiarity with air travel might produce.

Ironically, I usually enjoy movies in which investigators work to understand the cause of an accident – they’re essentially detective stories. I recently watched Charles Frend’s Cone of Silence (1960), in which responsibility for a crash is deflected from a design flaw to pilot error by an industry and system determined to protect itself, and I’ve seen Ralph Nelson’s Fate Is the Hunter (1964) many times, which similarly tries to determine what part pilot error played in a crash. What distinguishes Charlie Victor Romeo is its focus on the moment of crisis itself and the ways in which the flight crews react during the incidents – a focus which illuminates just how complicated the concept of “human error” can be. Responding moment by moment, making judgments under extreme pressure based on training, experience, even intuition, might produce a number of possible outcomes, but what looms over each incident is the sheer weight of a technology which dwarfs the human element. Just days after I watched the film, that door plug blew out of an Alaska Airlines Boeing in mid-air, almost like an epilogue to the film, hammering home the part the materiality of the plane itself plays in these incidents.

The film eases the audience into what we’ll be experiencing with an incident which, like the Alaska Airlines incident, avoided a catastrophic ending. A lack of attention to detail by a flight crew and air traffic control caused American Airlines Flight 1572 to come in too low when landing in Granby, Connecticut, hitting some trees and an antenna. The plane landed with minor damage and negligible injuries to those on board. The five incidents which follow were all far less fortunate. During a descent in Indiana, icing interfered with the controls of Simmons Airlines Flight 4184 and the plane crashed, killing everyone on board. A U.S. Air Force AWACS plane hit a flock of geese on take-off in Alaska and crashed, killing everyone on board. Japan Air Lines Flight 123 suffered a ruptured bulkhead during its climb, damaging controls in the tail; crew attempted to use engine thrust to manage a descent, but the plane crashed into a mountain with just four survivors. On United Airlines Flight 232 over Iowa, metal fatigue in an engine part caused a fan to disintegrate, the fragments cutting into the hydraulic system, eliminating the crew’s ability to control the plane, which crashed with 40% fatalities.

The longest section of the film illuminates the limitations of professionalism in the face of an anomalous situation which proves intractable to the crew’s ability to understand just exactly what was occurring. In 1996, an Aeroperu Boeing 757 took off from Lima and the crew immediately discovered that their instruments were providing erratic information about airspeed and altitude. The on-board computer kept giving them emergency warnings and they tried to figure out what was happening, to analyze what the confusing read-outs meant. Declaring an emergency, they requested an emergency landing back in Lima, relying on information from air traffic control about their actual speed and altitude. Yet that information wasn’t coming from ground radar, but rather from the plane’s own transponder … which meant that they were being fed back the same erroneous information shown by their faulty instruments.

Since it was night, over water, the crew were dependent on instruments which had become untrustworthy. They were lower than they believed and also flying slower than they believed, repeatedly stalling and losing more altitude until a wing clipped the water, partially breaking off. The plane crashed, killing everyone on board. Reliant on information provided by instruments, they became incapable of flying the plane and spent their energies during the emergency on trying to analyze why the instruments were behaving so erratically; they were locked into technician mode and rendered helpless.

The confusing instrument readings had been caused by a member of the ground crew who, during washing the plane, had taped over the ports which provided information about altitude, airspeed and vertical speed to the plane’s computer. The tape had not been removed after cleaning, essentially rendering the plane “blind”. Stuck at the unreliable controls, the crew directed all their efforts towards trying to get the instruments back to normal, though the actual problem was not with the instruments themselves, but with a few pieces of tape stuck to the belly of the plane – and as they struggled to figure out the problem, the plane descended, stalled, and hit the water.

By the end of Charlie Victor Romeo you have a sense of how lucky you are whenever you land safely and walk off a plane, and how easily your flight could have ended very differently.

The Dekanalog Blu-ray offers three different presentations of the film across two disks. Despite the simplicity of the conception – a single set and a handful of actors – it was shot in 3D and the first disk contains a digital 3D version plus a 2D copy, with director commentary. The second disk has an anaglyph 3D copy (only one pair of red/blue glasses provided – I guess they assume you’ll be watching it alone because it’s too disturbing to share with a friend), along with a number of extras. There’s a lengthy presentation by Captain Al Haynes about the crash of United Flight 232 in Iowa in 1989 (the final incident depicted in Charlie Victor Romeo), plus two scenes from the play recorded on stage, a couple of PBS Newshour reports, trailers and a booklet which reprints excerpts from the official investigation reports on each of the crashes.

While the decision to shoot on 3D does seem a little odd – the entire film is just a few actors sitting on a small set – I’m glad I watched the anaglyph version because it’s in black-and-white, which gives it an additional sense of clarity and precision. Watching the 2D colour version to listen to the commentary, it seemed more like a stage play, slightly removed from the documentary immediacy I’d felt on that first viewing. The commentary itself, with co-directors (and actors) Patrick Daniels and Robert Berger, provides a history of the stage production and the process of making a film within the self-imposed limitations of adhering closely to the voice-recorder transcripts without any kind of dramatic embellishments.

Charlie Victor Romeo is one of the most interesting releases I’ve come across in a while, the material itself and the filmmakers’ handling of it illustrating that spectacle is not necessary to provide a lasting visceral impact.

Comments