Satyajit Ray’s Apu Trilogy: Criterion Blu-ray review

Writing about an acknowledged classic of world cinema is always a daunting prospect. It’s even more intimidating – embarrassing confession here – when I’ve somehow managed over more than six decades of movie-watching never to have seen this work despite its reputation. I’m not sure why – it wasn’t a matter of deliberate avoidance, but rather that my path was never crossed by the films of Satyajit Ray until now, with the release of The Apu Trilogy in a dual-format edition from Criterion. At such moments, there’s always a fear that the work might not live up to its reputation. But there’s also the thought that I can’t possibly have anything to say that hasn’t already been said many times over.

The first fear was quickly allayed as I began to watch Pather Panchali and found myself immersed in, yes, a masterpiece, a film so rich in its observations of life and yet seemingly so effortless in its ability moment by moment to find the perfect image to express what it has to say. This feeling was sustained through all three films, which together convey an indelible sense of the flow of an individual life and the time, place and people which shape it. And thus, my second anxiety grew – all of this has been seen and understood and commented on by audiences and critics since the films were first released in the ’50s and as much as I have been moved by them, I doubt I have any original insights to convey – so apologies up front for the following no doubt trite and obvious observations.

Ray, a university-educated member of a family of artists and writers from Kolkata, had a successful career as a commercial artist and illustrator when he decided to become a filmmaker in his early thirties. At the time, India had the largest film industry in the world, one which was centred on large-scale entertainments which mixed music, romance and fantasy with flamboyant melodrama; Ray had no interest in any of this, but rather wanted to explore the real life of the Bengali people. Although rooted in the place and culture he was familiar with, and based on a revered novel by Bibhutibhushan Banerjee, his first film was influenced by foreign filmmakers he admired, including Vittorio De Sica, Jean Renoir and Aleksandr Dovzhenko.

That film, Pather Panchali (1955), was a radical project compared to typical Indian movies. Much of it shot on location in a small, poor village, with a cast of both professional (theatre) actors and amateurs, it took several years to complete, with long interruptions as Ray scrambled to find money to continue. His collaborators, including cinematographer Subrata Mitra, were as inexperienced as Ray himself, learning as they worked. Mitra was a stills photographer who had no experience with a movie camera, and yet the images he created are crucial to the film’s impact – the expressive attention to faces, to landscape, to movement and textures, give the film a powerful blend of physical specificity and an almost ethereal poetry.

Pather Panchali was a huge success, both internationally and at home so although it had not been Ray’s original intention, he followed it quite quickly with a sequel. Aparajito (1956) takes Apu into young adulthood, with style and tone changing to reflect his journey out of childhood. There again, Ray had no intention to continue the story, going on to make two other features in 1958, a comedy and a tragedy. It was at a press conference for the latter that he was asked if there would be another film about Apu and he surprised himself by saying yes, although he had no clear idea of where to take the story.

Apur Sansar (The World of Apu, 1959) diverged more from Banerjee’s novels than the previous films, reflecting both Ray’s increasing confidence as a filmmaker and his sense of ownership over the character, taking him into adulthood and a complex range of emotions which veer vertiginously from elation to abject grief.

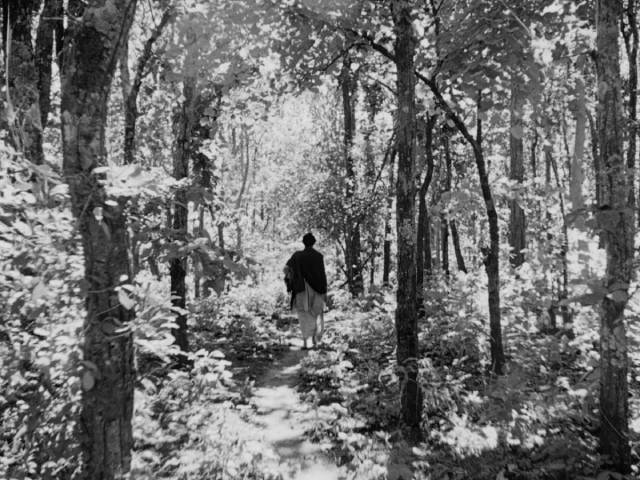

The Apu Trilogy is concerned with mood, tone and emotion rather than narrative, moving from a quiet contemplation of childhood through a growing awareness of the constraints imposed by a complex social and economic system and on to a maturity which brings with it responsibility and emotional pain. Even at the start, Ray’s work conveys a great deal while avoiding overtly dramatic events, drawing the viewer into its characters’ lives in a way which, when transformative events do occur, creates an almost overwhelming emotional impact. These characters, living in poverty, struggle day to day with the minutiae of survival – food, shelter, limited economic prospects and debt – an emotionally draining cycle punctuated occasionally by deeper traumas of loss and death. In this context, birth brings with it the potential for renewal and continuity while bearing a shadow of mortality from the moment the first breath is drawn.

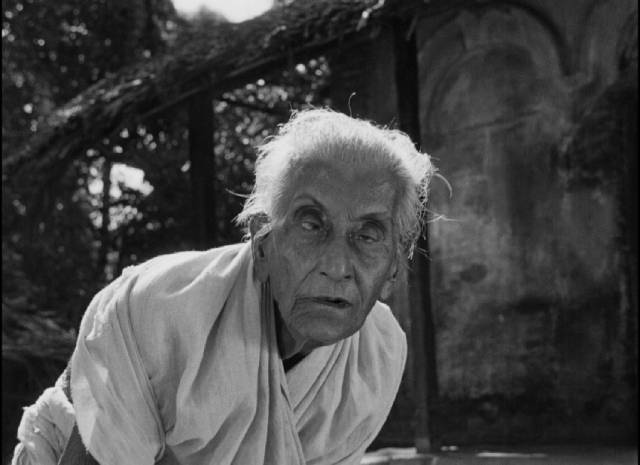

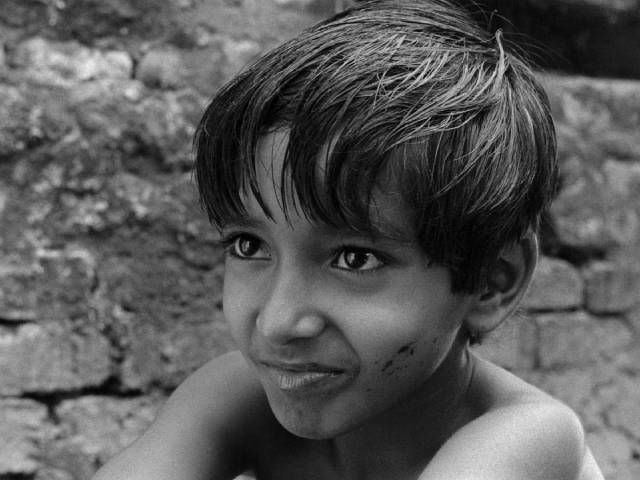

Although the title of the trilogy privileges Apu, the three films are equally – if not more so – centred on the women in his life, beginning even before he is born. With a father, Harihar Ray (Kanu Bannerjee), who’s a frequently absent itinerant preacher, the household comprises three generations of women – Apu’s mother, Sarbajaya (Karuna Bannerjee), who struggles to make ends meet in the face of crippling debt; elderly aunt Indir Thakrun (Chunibala Devi), who lives with the family despite on-going friction with Sarbajaya; and daughter Durga (initially played by Rinki Bannerjee, later Uma Das Gupta), a wild child given to stealing fruit from a neighbour’s orchard, which she surreptitiously gives to the aunt. Durga takes her new brother under her wing and together they explore the world around the village, drawn in particular to the railway which takes on an almost mystical quality with its promise of escape.

It’s the sudden, unexpected death of Durga which puts an end to village life; at the close of the first film Apu and his parents depart for a new life in Benares. Aparajito immediately emphasizes the drastic change with its opening shots of people bathing ceremonially on the shores of the Ganges before moving closer to reveal Harihar teaching on the steps and Apu now running wild in the narrow streets with other boys, while Sarbajaya cleans the courtyard of the tenement where they now live – still poor, still in debt, but stripped of privacy as the other residents come and go through the space occupied by the family.

Once again sudden death brings a drastic change. With Harihar gone, along with the meagre income brought by his preaching, Sarbajaya becomes a domestic servant for a wealthy family and she and Apu find themselves once again living in the country. With the limited prospects offered by taking on his father’s role as itinerant preacher, Apu asks his mother to allow him to go to school, hoping to improve his position in life. He proves an apt pupil, thriving and eventually earning a scholarship which takes him away to study in Kolkata. The life-long tension between boy and mother becomes a rift; he is all that remains of the family and she wants to keep him close, while he wants to break free of the limitations of poverty.

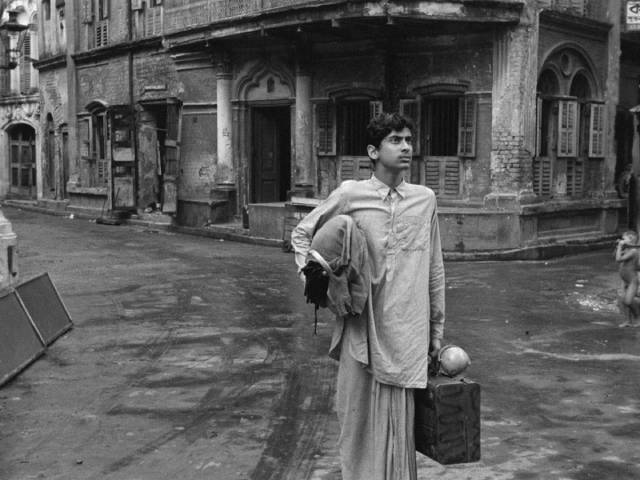

Life in the city, split between studies and work in a small printing shop, is hard and Apu increasingly puts off occasional visits home until it’s finally too late and he finds himself alone in the world. With few resources, he’s forced to leave university, but his unfinished studies make him over-qualified for the menial jobs he applies for. Living in a single room in a tenement, he works on a novel – which seems very much autobiographical, the story of a boy born into poverty in a small village; in debt, threatened with eviction, he dreams of a creative life, seemingly having learned nothing from his mother’s financial struggles.

Once again chance brings radical change when an friend from school arrives one day and invites him for a weekend in the country. Pulu (Swapan Mukherjee) is from a wealthy family and his cousin is about to be married. Arriving at the country house, Apu makes a good impression and when the wedding plans go awry, he finds himself taking the place of the (obviously mad) groom, returning to the city with the bride. Aparna (Sharmila Tagore) is a young girl, born into privilege, and the realization of her new husband’s poverty is initially devastating – but like Sarbajaya, she accepts her lot and the stresses which go with it and a genuinely warm and touching relationship develops between the pair.

This brief idyll is shattered once again by unexpected death and Apu sinks into despair when Aparna dies in childbirth. He refuses to have anything to do with his son, destroys his manuscript, putting an end to that dream, and disappears, wandering the world, doing menial jobs. Pulu eventually tracks him down working in a mine and stirs his conscience. Arriving at his in-laws’, he gets a frosty welcome and discovers that his child Kajal (Alok Chakravarty) is wilder than he was himself, distrusting and hostile, yet curious about this figure who calls himself father. An open-ended resolution finds father and boy forming a tentative bond, perhaps breaking with all the rules and constraints which have shaped Apu’s life since he was born into that impoverished village decades earlier.

While it’s apparent that Ray’s technical skills as a filmmaker had developed over the years, what is most remarkable about the Apu Trilogy is how subtle and expressive he was as an artist right from the start. He gets remarkable performances from the actors, no matter how small the role, the various children in particular seeming natural and unselfconscious. Though four separate actors play Apu at various stages – Subir Banerjee in Pather Panchali, Pinaki Sengupta and Smaran Ghosal in Aparajito as he grows older, and Soumitra Chatterjee in Apur Sansar – there is a seamless sense of continuity to the character. But it’s the women who make the strongest impression, with Karuna Bannerjee anchoring the first two films, given remarkable support in Pather Panchali by Chunibala Devi as the aunt and Runki Banerjee and Uma Das Gupta as Durga, while thirteen-year-old Sharmila Tagore is radiant as Aparna in Apur Sansar.

Equally important is the work of Subrata Mitra behind the camera. In particular, the many night scenes and dark interiors display an impressive ability to highlight crucial details in the darkness. Another key contributor is editor Dulal Dutta, who gives the films their very particular rhythm, rooted in visual moods and emotional arcs rather than dramatic events. There is a great deal of poetry in the Apu Trilogy, and yet the films give an impression of lives observed rather than artfully constructed.

Ray’s work here has frequently been termed “universal” in its ability to connect audiences so powerfully with the lives of these characters; but it seems rather that this identification with those whose experience and circumstances are so different from those of comfortable western viewers arises from the filmmaker’s specificity, the details and textures of life depicted in precise, evocative imagery. Rather than generalizing the experience of Apu, his family, friends and social connections, Ray’s creative alchemy draws us into that world so that we can comprehend these lives in all their complexity – we find a shared humanity made all the more poignant for the myriad differences between us and what we are being shown. If these lives are constrained by social, economic and historical circumstance, Ray nonetheless invests them with remarkable depth and breadth and gives the overall work a rhythm and flow which feels like life itself – from the sense of childhood freedom which is not yet aware of limitations in the first film, expanding in the second to encompass both country and city life and the exhilaration of beginning to take charge of one’s own trajectory, to the richness and pain of the third film’s emotional landscape. Made at the beginning of Ray’s career, the trilogy is a remarkable achievement which fully deserves its status as a masterpiece.

*

The disks

Criterion’s six-disk dual-format edition uses 4K scans and restoration done by the Academy Film Archive in collaboration with L’Immagine Ritrovata in Bologna. This represents an heroic effort to save the films; after Ray’s death in 1992, an effort began to rescue his work from decay and the original negatives of the Apu Trilogy were moved to a lab in London. However, before work got underway, a fire destroyed much of what was stored in the lab, and Ray’s negatives were severely damaged. Although it was unclear what could be salvaged, everything that survived was shipped to the Academy Film Archive in Los Angeles, where it remained until techniques were available to work with the material. Eventually, extensive work managed to save 40% of the Pather Panchali negative and 60% of Aparajito, though Apur Sansar was entirely lost. With other sources being found in various archives, it was possible to reconstruct all three films and, despite some lingering signs of damage and wear, the image on the disks is quite stunning. The soundtracks are all very clean as well.

The supplements

Although, surprisingly, there are no commentary tracks, a number of extras spread across the three disks provide valuable context and analysis. There are a couple of audio recordings of Ray (1957, 14:36; 1958, 14:30) in which he discusses his work. There are a number of interviews with actors and crew – Soumitra Chatterjee (7:14), Shampa Srivastava (Runki Banerjee, 16:29), Sharmila Tagore (12:34), Soumitra Chatterjee and Sharmila Tagore (15:07), and camera assistant Soumendu Roy (12:34). There are critical interviews with writer Ujjal Chakraborty (11:26), Ray biographer Andrew Robinson (37:45) and BFI head Mamoun Hassan (43:32). There’s an archival Educational Television documentary by James Beveridge from 1967 which observes Ray at work (28:59) and a brief excerpt from a 2003 documentary about Ravi Shankar in which the musician talks about his scores for the Apu Trilogy (5:55). A short clip from the 1992 Oscar broadcast, at which Ray was given an honorary award, has the filmmaker addressing attendees via television from his hospital bed shortly before he died (3:03).

Finally, there are two brief pieces by :: kogananda about the work involved in restoring the films (2:49, 12:31), and the booklet contains essays by Terrence Rafferty and Girish Shambu, as well as some of Ray’s storyboards for Pather Panchali.

It’s taken me a very long time to get to the Apu Trilogy, but that may not be a bad thing as it’s likely that this Criterion set offers the best presentation they’ve likely had since their original theatrical screenings. My wait has been very well rewarded.

Comments