Winter 2024 viewing, part one: Severin

Time to catalogue what I’ve been watching over the past couple of months, but haven’t yet mentioned. As always, this is a mix of throwaway low-brow entertainment and more interesting genre movies, some of which deserve more than a passing comment … if only I had more time to write. It almost goes without saying that the list is dominated by Severin and Vinegar Syndrome releases, many purchased during their respective Black Friday sales back in November.

Severin

The Dead One (Barry Mahon, 1961)

I know I’m a sucker, but I just can’t help myself, so as usual I opted for Severin’s big sale bundle even though it contained a couple of movies I had no interest in. Perversely, those were the first two I watched (“just to get them out of the way”). These were Barry Mahon’s The Dead One (1961) and Brett Piper and Samuel M. Sherman’s Raiders of the Living Dead (1986). The former is a rather dull zombie movie from New Orleans which begins with a long tour of the city’s jazz clubs before heading to the bayou and a story about a voodoo priestess who raises her dead brother to kill her cousin’s new bride in order to hold onto the plantation which should go to him now he’s married. That the priestess is white and much of the action takes place in the old slave quarters among her Black workers produces some uncomfortable echoes of the Old South’s historical crimes.

Raiders of the Living Dead (Brett Piper & Samuel M. Sherman, 1986)

Raiders of the Living Dead is an odd illustration of what can happen in the underfunded realms of regional filmmaking when a distributor figures he can do better than the original filmmaker. Brett Piper shot a zombie movie called Dying Day around the time he was making his Matt Mitler-starring sci-fi duo Battle for the Lost Planet (1986) and Mutant War (1988), but it remained unfinished until distributor Samuel M. Sherman picked it up, shot new material, re-edited it and tried releasing it as Dark Night. When that didn’t work, he shot some more material, re-edited it again, and put it out as Raiders of the Living Dead, trying to cash in on audience associations with both Steven Spielberg and George A. Romero. Now that’s hubris! Severin’s disk includes all three cuts, and perhaps it’s no surprise to discover that Piper’s version is the most coherent, though Sherman’s second attempt does have the absurd touch of a teen who converts his grandfather’s laserdisc player into a zombie-killing death ray.

Zombie Holocaust (Marino Girolami, 1980)

Several of the new releases were 4K upgrades of disks I already owned (my resolve to resist double-dipping remains weak). Marino Girolami’s Zombie Holocaust (1980) looks the best here it likely ever will (I haven’t re-watched the alternate U.S. Dr. Butcher M.D. cut yet, but no doubt it’s similarly improved); obviously drawing heavily on Lucio Fulci’s Zombi (1979), right down to casting Ian McCulloch as the hero, it also throws in elements from the Italian cannibal genre, with heroine Alexandra Delli Colli destined to be queen of the tribe which eventually takes care of the evil doctor (Donald O’Brien gleefully popping open skulls and transferring brains for rather vague scientific reasons) and his undead minions.

Dellamorte Dellamore (Michele Soavi, 1994)

The core of the bundle were three dual-format editions of Michele Soavi’s The Church (1989), The Sect (1991) and Dellamorte Dellamore (1994) – for some reason his feature debut, StageFright (1987) was omitted. While The Church and The Sect had been given impressive releases by Scorpion in 2018, Severin upgrades to 4K and includes soundtrack CDs (the latter helping to justify the double-dip); the biggest improvement, though, is the new mastering of Dellamorte Dellamore, which is vastly better than the disappointing Shameless Blu-ray, with a rich, detailed image which holds up even in the darkest scenes. Soavi, a protege of Dario Argento, had entered the Italian horror scene as the genre was already faltering and his first four features serve as a kind of coda to the golden era which ran from the late ’70s to the end of the ’80s, with the unclassifiable Dellamorte Dellamore investing a degree of wild invention, satirical social commentary and apocalyptic tragedy into a unique revision of the zombie sub-genre. All three releases are packed with extras to provide historical and critical context for Soavi’s work before changing circumstances sent him into television production with an emphasis on crime rather than horror.

The Spider Labyrinth (Gianfranco Giagni, 1988)

Severin diverged from this more familiar territory with a couple of other releases. Gianfranco Giagni’s The Spider Labyrinth (1988) is an atmospheric, often dream-like mix of horror and paranoid thriller in which an American academic working on an obscure international project is sent to Budapest to find out why one participant has fallen silent. After a cryptic meeting with that colleague, the man apparently commits suicide and the American is drawn into what seems to be a vast conspiracy rooted in an ancient religion which serves a spider god. The air of unreality escalates, with the city seeming to become empty except for the cult members themselves, who perform their ceremonies in vast underground caverns. The whole nightmare climaxes with the bizarre rebirth of an avatar of the spider god and the cult’s influence becomes inescapable.

Stir (Stephen Wallace, 1980)

Worlds away is Stephen Wallace’s Stir (1980), an Australian movie based on an actual prison riot. Bleak and brutal, it’s relentless in its depiction of a dehumanizing system which, through its violent methods of “discipline” and control, guarantees a violent reaction from convicts who have no means of redress. Unapologetically on the side of the prisoners, the film depicts the guards and prison authorities as sadistic monsters in an escalating series of confrontations leading to the prolonged climactic riot. Bryan Brown is effective as a con who just wants to keep his head down and serve his time but is inevitably drawn in as a leader of the rebellion.

Mardi Gras Massacre (Jack Weis, 1978)

I also picked up a copy of an earlier Severin release, Jack Weis’s Mardi Gras Massacre (1978), an awkward mix of slasher, police procedural and horror, quite obviously influenced by Herschell Gordon Lewis’s Blood Feast (1963). A pair of cops try to track down a creepy guy who is picking up prostitutes and killing them in an obviously ritual way – he needs to sacrifice a certain number of “evil” women before Mardi Gras in order to raise the Aztec goddess he worships. Meanwhile, one of the cops becomes involved with a witness, but the relationship is doomed by his rampant misogyny.

Cushing Curiosities (Various, 1960-74)

Since Black Friday, Severin has released two new box sets. Cushing Curiosities collects a random assortment of items from the fringes of the actor’s prolific career. Although he’d already been in the business for two decades and had become a star in Hammer’s Gothic horrors in the past few years, he was still taking supporting roles in 1960 when he appeared in Charles Frend’s Cone of Silence, in which he plays a rare unlikable character as a pilot only too willing to destroy another man’s reputation after an airliner crashes. That same year he appeared as a research scientist in John and Roy Boulting’s Suspect, a minor Cold War thriller about a team which comes up with a cure for plague which the government suppresses because it might help the Commies with their biological warfare programs; a gullible member of the team is duped into selling the secret to the Russkies, thus confirming the wisdom of bureaucrats who would stifle medical advances for political reasons.

Quentin Lawrence’s The Man Who Finally Died (1963), the only movie in the set I’d already seen, is another dose of Cold War paranoia in which an embittered man (Stanley Baker) is tricked into exposing a defecting scientist; blinded by his personal feelings, he doesn’t realize until too late that he’s been used – largely because those helping the scientist obtusely refuse to be open and honest with him. Cushing plays one of those people, a doctor serving in a camp for people displaced after the war.

The actor took the lead role in the BBC’s 1968 follow-up to their earlier series of Sherlock Holmes adaptations starring Douglas Wilmer. Although he had played the part previously in Hammer’s The Hound of the Baskervilles (1959), I have to admit that I prefer Wilmer’s version, though these six surviving episodes (of an original sixteen) are enjoyable enough. It’s a pity that two of them retell The Hound of the Baskervilles, as the limitations of television result in an inferior adaptation compared to the Hammer film.

Robert Hartford-Davis was a minor British exploitation filmmaker. Although you might lump him in with Pete Walker, he lacked Walker’s consistency … a glance at his filmography shows the random nature of someone who would take whatever came along without displaying any clear personal interest in his material. Among exploitation, comedy and even a musical, he made several horror movies in the ’60s before heading to the U.S. for a couple of blaxploitation movies. His best work is Corruption (1968) and Beware My Brethren (1972), both of which benefited from better-than-average casts – the former has Cushing in his sleaziest role, along with Sue Lloyd, Kate O’Mara, Anthony Booth and David Lodge; the latter Patrick Magee, Ann Todd, Tony Beckley and David Lodge again. The much-derided Blood Suckers aka Incense of the Damned (1971) has all the earmarks of a movie cobbled together out of incomplete material and Hartford-Davis actually had his name taken off it after serious producer interference.

Hoping to pull his life together, a university student (Patrick Mower) heads to Greece and disappears. His concerned friends (Alexander Davion and Johnny Sekka) and fiancee (Madeleine Hinde), the daughter of his mentor (Cushing), go after him. Tracing his path, they discover that he has fallen under the sway of a cult devoted to ancient deities; they conduct orgies and human sacrifice and their leader (Imogen Hassell) turns out to be a vampire… At one point the movie stops dead for ten minutes to show a hedonistic orgy, shot psychedelically to obscure/reveal copious amounts of nudity (a sequence inserted by the producers which has nothing to do with the story, but pads the running time to feature length). The cast, which also includes Patrick Macnee, Edward Woodward, William Mervyn and David Lodge yet again, do what they can with the incoherent script and cinematographer Desmond Dickinson makes the most of the Greek locations, but in the end one feels frustrated because it seems that there was a much more interesting movie in the material that never quite emerges.

As big a mess as Blood Suckers is, it’s at least somewhat entertaining, which is more than can be said for Tender Dracula (1974), the sole directorial effort of noted producer Pierre Grunstein, and the only time Cushing ever played a vampire himself. Painfully unfunny, it has a couple of boorish television writers and their girlfriends visit a famous horror star who has announced that he wants to spend the rest of his career making only romances. As the night wears on, it becomes obvious that the actor is actually a real vampire with romantic inclinations. Cushing, ever the pro, does his best to maintain his dignity in the midst of the misfiring slapstick and rather a lot of “erotic” scenes, but the tone is all over the place and in the end the best thing here is the castle location, nicely photographed by the prolific Jean-Jacques Tarbès.

Danza Macabra vol 2 (Various, 1964-72)

Severin’s latest box set is Danza Macabra vol 2, a follow-up to the first set they released last May. More elaborate this time, it once again gathers some lesser-known titles, though anchored this time by a three-disk edition of Antonio Margheriti’s Castle of Blood (1964), the fourth of Barbara Steele’s Italian Gothic horrors, and the first of two she made with Margheriti. Previously, Margheriti had made a comedy, a couple of sci-fi movies (a genre he would return to several times during the decade), and a couple of historical fantasies. When co-writer and original director Sergio Corbucci dropped out due to scheduling conflicts, Margheriti stepped in and proved himself more adept at handling the story’s Gothic trappings than in the previous year’s The Virgin of Nuremburg, helped no doubt by the better script.

It may just be coincidence, but Castle of Blood shares significant story elements with Mario Bava’s masterpiece Lisa and the Devil (1972): a protagonist is drawn to a run-down villa where they witness ghosts re-enacting the traumatic events surrounding their deaths. In this case, though, that protagonist is a man, a journalist who takes a bet with the estate’s owner and his friend Edgar Allen Poe to spend the night in the supposedly haunted castle. Once inside, he encounters – and falls for – the alluring Steele, only to see her and her husband murdered by her brutish, jealous lover. An element of vampirism creeps in when we learn that the ghosts need to feed on the blood of a living person once a year to remain active as they endlessly repeat the violence which destroyed them.

The set includes a 4K disk with both the original Italian Danza Macabra cut and the U.S. Castle of Blood version, plus separate Blu-rays for each version and a large collection of extras, including a commentary on the Italian cut plus multiple interview featurettes. This could easily have been a stand-alone release, and feels very generous in the context of the box set.

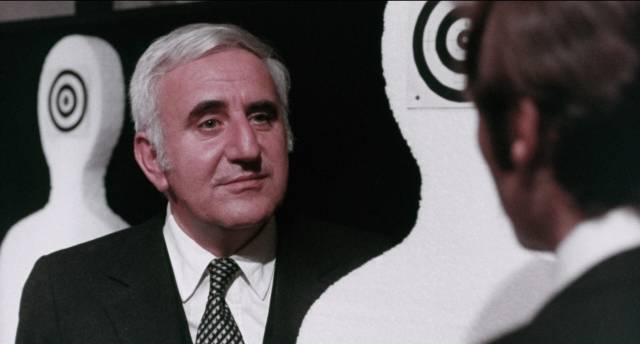

The next two disks contain the four episodes of Jekyll (1969), a mini-series adaptation of Robert Louis Stevenson’s 1886 novella The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. This much-adapted story is so familiar that it presents problems for a filmmaker tackling a new version – there’s no suspense, of course, about what’s going on and what the relationship is between the respected doctor and his sinister protege – so what matters more is the stylistic choices made along the way. While the series seems somewhat attenuated at almost four-and-a-half hours, co-writer/director/star Giorgio Albertazzi has modernized the story and set it among coldly modernist locations which are reminiscent of productions from that period which used existing architecture to suggest a dehumanized future – Elio Petri’s The 10th Victim (1965), for instance, or David Cronenberg’s Stereo (1969) and Crimes of the Future (1970). It also seems obvious that Albertazzi drew on his own experience as the star of Alain Resnais’ Last Year at Marienbad (1961) in creating images of characters trapped within and dwarfed by architectural spaces.

The narrative is viewed through the eyes of Jekyll’s attorney Utterson (Massimo Girotti), who is disturbed to find a connection between the violent Hyde and his client and friend. Jekyll is a researcher and university lecturer whose experiments with DNA have led to him splitting into two people, with the dark half gaining increasing power despite the doctor’s efforts to suppress him. But we, as viewers, already know all this so as the episodes take their time to get to the revelation which is shocking for the other characters we remain rather detached. I guess I wanted to like this rarity more than I did. The cast is certainly good, and despite obvious budgetary limitations the images created by cinematographer (and future director) Stelvio Massi do create an effective mood – though compromised by the damaged broadcast tape master, which is the only existing source.

The next disk contains the movie I was most interested in, Corrado Farina’s They Have Changed Their Face (1971), the first of his two features – the better-known Baba Yaga followed in 1973. An allegory of predatory Capitalism, it uses Gothic tropes to depict powerful corporate types as literal vampires who use their economic power to transform consumers into compliant sheep ripe for exploitation. The satirical intent is signalled early with characters named Harker and Helsing occupying positions in the corporate structure of an automobile company which, we eventually learn, is owned by one Giovanni Nosferatu (Adolfo Celi, who six years earlier had played Bond villain Largo in Thunderball). Mid-level executive Alberto Valle (Giuliano Esperati) is summoned to visit Nosferatu on his estate on a gloomy, fog-bound mountain. Passing through an almost-deserted, decaying village populated by silent, superstitious peasants, he picks up a woman who tries to divert him away from the estate, but in classic fashion he ignores her warning (and attempt to seduce him) and enters a mysterious realm where he is offered power and wealth.

Strange things occur, with corporate business taking on the forms of religious ritual and advertising merging with human sacrifice. Sneaking around, Alberto discovers evidence that he has been destined for his role in the company since birth, that there is no free will and though repulsed by what he has learned resistance is futile. Farina is less interested in the traditional elements of horror than the satirical treatment of business – the choice of a car manufacturer echoes Juraj Herz’s satirical horror Ferat Vampire (1982) – while Alberto’s situation is similar to that of many protagonists in the paranoid political thrillers which were beginning to appear in the early ’70s. Although the film is preceded by a note that the only remaining source is a colour-faded print, the image is quite good, the muted colour appropriate to the dank atmosphere. There are two commentaries (one with Farina and his son recorded before the director’s death in 2016), plus interviews and various pieces of the director’s non-feature work – short films, commercials and documentaries.

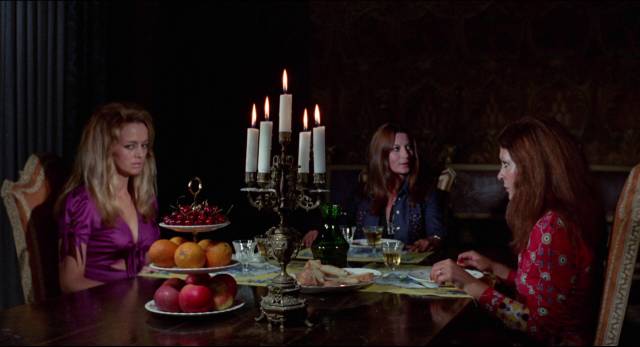

Last – and very much least – there’s The Devil’s Lover (1972), the second of three features by someone named Paolo Lombardo. This barely qualifies as horror, leaning more towards an erotic period movie though it can’t seem to muster any conviction in that direction either. The most notable thing about it is the presence of Rosalba Neri, a major genre star in the ’60s and ’70s (she was the lead in the previous Danza Macabra set’s Lady Frankenstein [1971]). She and two friends arrive at a castle reputed to belong to the devil and are invited to stay the night; sneaking around after dark, she passes out and wakes in medieval times as a woman involved in a love quadrangle. Jealousy, bitterness, curses and murder ensue, possibly spurred on by the devil himself. It’s all rather vague and slack and limps to an end after only seventy-five minutes. The 2K transfer is quite striking, supplemented with a commentary, a featurette on Neri and an interview with co-star Robert Woods, better-known for his roles in westerns. As if to compensate for the inclusion of this dud, Severin have included a CD of Elvio Monti’s score, which is definitely better than the movie itself.

*

Next: Vinegar Syndrome

Comments