Winter 2024 viewing, part four: More other labels

I’d intended to sum up my winter viewing quickly, with a few lines about each movie, but here I am with the fourth post in a row and no end in sight … this is probably why people’s eyes tend to glaze over when I start talking about movies over lunch or dinner! I need to wrap this up as I’ve already begun to fall behind again with comments about my most recent viewing – some BFI releases, Arrow’s Psycho box set, more Vinegar Syndrome (the February package recently arrived with another fifteen movies), and a stack of old Universal movies on Blu-ray from Eureka. So here are my sketchy thoughts about an odd assortment of releases from a variety of labels.

Kino Lorber

I picked up a couple of titles from Kino Lorber representing the later work of two directors whose careers began in the ’50s, both of whom were past their prime when these movies were released.

The Challenge (John Frankenheimer, 1982)

In some ways, John Frankenheimer is hard to pin down. A liberal from the East Coast who learned his craft in the days of live television drama in the ’50s – along with people like Sidney Lumet and Franklin J. Schaffner – he gives the impression much of the time of being more interested in the technical challenges of his projects than the thematic implications. Birdman of Alcatraz (1962) is a quintessential liberal take on a perennial issue (the justice system and the consequences of incarceration), while The Manchurian Candidate (also 1962) seems precariously poised between satirizing Right-wing anti-Communist paranoia and confirming the validity of that paranoia. He followed Seconds (1966), another paranoid thriller, and a genuine masterpiece, with Grand Prix (also 1966), a movie whose subject and theme was nothing more than the technical challenge of getting the camera as close as possible to formula one race cars.

Bouncing from genre to genre, his work after the late ’70s displays little of the creative play and personal commitment of the early films, though both French Connection II (1975) and Black Sunday (1977) are exemplary thrillers; but he followed those with the dud Prophecy (1979), which just proved that he had no affinity for horror. I’ve seen quite a few of his movies from the ’80s and ’90s (his reviled The Island of Dr. Moreau [1996] is a particular favourite of mine, and the director’s cut of Reindeer Games [2000] is a pretty good neo-noir heist movie), but had never come across The Challenge (1982) until I found a copy when I was recently trading in some old DVDs. Like most of his work, it’s technically proficient – he certainly knew how to put a movie together – but it’s stylistically anonymous and could have been made by any number of other competent filmmakers.

It’s also occasionally uncomfortable, belonging to a sub-genre which has Western directors and stars engaging with the Japanese underworld. This goes back to Sam Fuller and House of Bamboo (1955) and includes Sydney Pollack’s The Yakuza (1974) on up to Ridley Scott’s Black Rain (1989). These movies tend to use cultural difference as an exotic form of narrative decoration and, when compared to actual Japanese movies with similar narrative elements, remain largely superficial. The Challenge, like The Yakuza, leans towards romanticizing the culture whose surface it skims, but also occasionally can’t resist transforming that culture into something disturbingly alien – Frankenheimer lingers on a banquet at which the characters eat dishes which are not only raw but still actually alive, an unpleasant spectacle which is supposed to have comic overtones as the American protagonist gets drunk to cope with his disgust and eventually flees the room to throw up.

That protagonist is Rick (Scott Glenn), a washed up boxer hired by a Japanese man to help smuggle a samurai sword back into Japan from the States. This is one of a pair belonging to a family which was irrevocably split when the younger brother balked at the ceremony in which the swords were passed to the eldest son. Decades later, both brothers seek to reunite the swords and Rick finds himself caught in the middle of a deadly feud. The two brothers are traditionalist Yoshida (Toshiro Mifune), who is master of a martial arts dojo, and Hideo (Atsuo Nakamura), an absurdly wealthy industrialist who lives within a vast futuristic fortress of Capitalism. Rick is rather dumb and uncomprehending; paid by Hideo to help steal the sword, he becomes Yoshida’s student and has to learn some hard lessons about honour before making the right choice and (after what seems like just a few days of training) engaging master swordsman Hideo in a fight to the death, earning himself the position of Yoshida’s honorary son – because the master unfortunately only has a daughter, Akiko (Donna Kei Benz), who obviously isn’t worthy to receive the two swords when they’ve been reunited.

I wanted to like The Challenge more than I did – not only was it directed by Frankenheimer, it was co-written by John Sayles – but the air of cultural tourism is often uncomfortable and Scott Glenn’s Rick is not a very appealing hero. There are few indications of the visual style for which Frankenheimer was known (and occasionally criticized); he gets the job done, but gives no indication that he was particularly engaged by the material.

Hustle (Robert Aldrich, 1975)

Frankenheimer had another two decades of work ahead of him after The Challenge, but Robert Aldrich was in the final stretch of his thirty-year career when he followed the commercial hit The Longest Yard (1974) with the anomalous Hustle (1975). A hyper-masculine filmmaker who had nonetheless made four female-centric movies in the ’60s – movies which pathologized their female characters within frameworks of Gothic melodrama (from What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? [1962] and Hush .. Hush, Sweet Charlotte [1964] to The Legend of Lylah Clare and The Killing of Sister George [both 1968]) – he re-teamed with star Burt Reynolds for the only movie in his filmography which could charitably be termed a love story. It’s also a neo-noir police procedural in which women seem able to survive only by exploiting their sexuality for money.

The most striking aspect of the movie is the almost incomprehensible pairing of Reynolds with Catherine Deneuve as a couple involved in a rather fraught relationship. He’s Phil Gaines, a cop, and she’s Nicole Britton, a classy prostitute; his reluctance to commit means that he has to repress his resentment about her profession – she’d give it up if he’d marry and support her, but he can’t admit his feelings and doesn’t make enough money to compensate for the income she’d lose. While they navigate these emotional and financial waters, he’s called in to investigate the death of a young woman on the beach. The coroner rules it a suicide – she drowned under the influence of drugs – but her embittered father’s angry complaints that the police don’t care about ordinary people prick his conscience and, against the orders of his commander, Santoro (Ernest Borgnine), Gaines starts to investigate.

The dead girl, Gloria Hollinger (Colleen Brennan), was a runaway who had slipped into prostitution and she was last seen at a party on the yacht of high-powered lawyer Leo Sellers (Eddie Albert). Gaines’ digging uncovers Sellers’ connections to organized crime and union corruption, with the death of Gloria being a minor side issue. With little chance of nailing Sellers in the girl’s death, Gaines ditches any semblance of professionalism and essentially helps Gloria’s father (Ben Johnson) carry out an extra-judicial execution. All this emotional turmoil helps Gaines decide that it’s time to accept his own feelings and marry Nicole … but this being the ’70s and neo-noir, fate steps in and he abruptly dies in a random liquor store hold-up.

Back in the ’70s, I didn’t think much of The Longest Yard, and I liked Hustle much more than most critics. Re-watching both recently, my opinion of the former has risen, while the latter is obviously more problematic than I remembered. Apart from the clashing styles of Reynolds and Deneuve (what is this elegant Frenchwoman doing hooking in L.A. and doing phone sex sessions at home while her boyfriend sits and seethes within earshot?), Gaines is pretty toxic. When his conflicted feelings become too much, he becomes physically abusive, hitting Nicole and almost raping her. Whether Reynolds was trying to stretch beyond the easy-going charm of his usual screen persona or this aggressive masculinity was simply another facet of that supposed charm, the character becomes unappealing and Nicole’s decision not to leave him, given her own toughness, seems more like something imposed by scriptwriter Steve Shagan than a plausible choice by the character.

Both Kino Lorber disks have decent transfers and feature a commentary track.

*

Indicator

Night Has a Thousand Eyes (John Farrow, 1948)

John Farrow’s Night Has a Thousand Eyes (1948) is an oddity, a not entirely successful blend of noir and horror made at a time when Hollywood was still uncomfortable with the idea of taking the supernatural seriously. Adapted from a Cornell Woolrich novel, it has Edward G. Robinson as phony stage clairvoyant Triton, who one evening suddenly starts to have real visions of the future. He abandons the act he performs with his fiancee Jenny (Virginia Bruce) and friend Whitney (Jerome Cowan) when he sees Jenny dying in childbirth. After he disappears, having told Whitney where he can strike oil and become rich, Whitney and Jenny marry and she does indeed die giving birth to Jean (Gail Russell). Whitney becomes rich, Jean grows up, and Triton moves to L.A. where he can watch over them unobserved.

He only makes his presence known when he gets a vision of Whitney dying in a plane crash and goes to warn Jean. But he’s too late; the plane crashes and Whitney dies. Jean’s fiance Elliott (John Lund) thinks Triton is a blackmailer and when it’s discovered that the plane was sabotaged, the police suspect he had something to do with it. He predicts that Jean herself will be murdered and the police lock him up. Everything converges at the Whitney mansion where company executives have gathered to decide the future of the business. The police set up surveillance to watch over Jean because of the apparent murder threat, and Triton, having convinced the cops that he really can see the future, shows up at the appointed hour and sacrifices himself to save the woman who, if not for the curse of his clairvoyance, might have been his own daughter.

Although the script by Barré Lyndon and Jonathan Latimer doesn’t quite manage to balance the noir and supernatural elements, Farrow does generate an appropriate sense of fatalistic gloom with the help of cinematographer John F. Seitz, and Robinson gives a fine, tormented performance, ably supported by William Demarest as the skeptical Lieutenant Shawn and Gail Russell, who a few years earlier had played the tragic heroine in another atmospheric supernatural tale, Lewis Allen’s The Uninvited (1944), and would co-star immediately after Farrow’s film in Frank Borzage’s poetic noir Moonrise (1948). Indicator’s Blu-ray has a 2K transfer which brings out the moody qualities of Seitz’s cinematography; supplements include a commentary, a featurette on Farrow, and a couple of radio adaptations of the story.

*

Eureka/Masters of Cinema

Eureka’s Masters of Cinema line continues to issue exemplary editions of foreign-language genre movies along with more predictable classics of world cinema.

The Great Silence (Sergio Corbucci, 1968)

Sergio Corbucci had made twenty features in fourteen years when he turned out his first two westerns in 1964; Massacre at Grand Canyon is fairly routine, while Minnesota Clay begins to show something more interesting (a gunfighter protagonist who seeks revenge as he gradually loses his eyesight) – but it was Corbucci’s third western which declared him a master of the genre. Django (1966) brings elements of surreal horror into its story of an enigmatic character who becomes involved in a conflict between the Klan and Mexican revolutionaries. One of the defining masterpieces of the genre, Django was followed by almost a dozen more westerns over the next decade. While these were uneven, and a number of them leaned into comedy, among them was perhaps the darkest, most nihilistic movie in the genre, a grim masterpiece which may be the crowning achievement of Corbucci’s four-decade career.

The Great Silence (1968) is one of the most uncompromising depictions of Manifest Destiny and the corruption at the heart of Capitalism put on film, its snow-bound mountain setting making it an interesting companion to Robert Altman’s masterpiece, McCabe and Mrs. Miller (1971). Jean-Louis Trintignant plays the enigmatic protagonist, nick-named Silence because he can’t speak, having had his throat cut and his vocal chords severed as a child. (This was a creative way of getting around language issues as the actor didn’t speak English.) As the movie begins, he rides out of the wilderness into an ambush in the snow, quickly dispatching the men who try to kill him. We only learn later who he is and why he’s been targeted.

Meanwhile, up in the mountains a community driven from their homes by business interests in the nearby town have been designated outlaws, each and every one with a price on their head. Gangs of ruthless bounty hunters scour the mountain, reaping profit from murder as they ignore the “… or alive” option on the wanted posters. All of this is driven by the banker Henry Pollicut (Luigi Pistilli), who has used his position as the arbiter of “the law” to steal land and condemn those he has stolen from. In a flashback, we learn that among his early victims were Silence’s parents and the boy’s throat was cut to ensure that he couldn’t name Pollicut and his henchmen.

Now a deadly gunfighter, Silence has come to exact his long-brewing revenge. Aiding the displaced community is a side-product of his mission as he methodically takes on the bounty hunters, aligning himself with the well-meaning but ineffectual Sheriff (Frank Wolff) and becoming involved with the widow of one of the gang’s victims (Vonetta McGee at the start of her career and a few years away from co-starring in Blacula [1972]). All of this sets up a classic conflict which raises particular expectations. But in this world things don’t play out according to formula. The forces of Capital and the “law” they control outweigh decency and righteousness and preclude a satisfying fulfillment of Silence’s long-sought retribution. The final stretch is the most abject and hopeless in the genre, the complete obliteration of decency and the triumph of greed and cruelty.

Much of the film’s final dismaying power comes not from Pollicut, who is a fairly standard villain, but rather from Tigrero aka Loco, the leader of the bounty hunters played by Klaus Kinski in his finest performance as a Western villain, and one of his best performances outside of his collaborations with Werner Herzog. A relentless avatar of psychotic cruelty given license by “the law”, he dominates the film, and Silence, no matter how skilled, is finally no match for him. In the genre as a whole, the climactic confrontation between good guy and bad guy(s) provides catharsis, the exhilarating release of the tensions which have accrued along the way; here, Corbucci thwarts that audience satisfaction, leaving the viewer stunned and hopeless. This was made the year before Easy Rider (1969) with its abrupt, fatalistic conclusion, but The Great Silence provides a far harsher portrait of the rot underpinning the self-aggrandizing American myth.

The Masters of Cinema Blu-ray has a gorgeous 2K transfer supplemented with no Less than three commentaries, an archival documentary about the genre which includes some on-set material from the production, featurettes on the genre and Corbucci, and a pair of alternate endings in which the distributor tried to get Corbucci to soften the conclusion – in one, the climactic slaughter is simply cut out, leaving the film without a resolution; in the other, Silence and the Sheriff rally at the last minute and kill all the bad guys.

The Fall of Ako Castle (Kinji Fukasaku, 1978)

After almost a decade redefining the yakuza genre, Kinji Fukasaku changed direction in the late ’70s as that genre faced a precipitous decline in popularity. In 1978, he went in two very different directions – with the fantasy Message from Space and the historical Shogun’s Samurai. The latter proved more amenable to his talents and he quickly followed it with an episode of a television series called The Yagyu Clan Conspiracy and The Fall of Ako Castle (both also 1978). The latter, also released as Swords of Vengeance, was that year’s attempt by Toei to produce a prestige film for the national arts festival (as they had done in 1964 with Tadashi Imai’s Revenge), for which they opted for a new version of the beloved and much-told story of The 47 Ronin. That aim, along with creative differences between Fukasaku and star Kinnosuke Nakamura, who had starred in Shogun’s Samurai, resulted in a more restrained style than the director had developed in his yakuza films.

At 159 minutes, The Fall of Ako Castle has a deliberate pace, allowing the familiar story to unfold with numerous digressions and character details which gradually form a critique of the narrative. In a tale of injustice and loyalty, the 47 Ronin stand as exemplars of samurai honour, warriors who sacrifice themselves for the principles of clan loyalty and a selfless willingness to die for their master. But in Fukasaku’s telling (scripted by Koji Takada, who had written a number of Fukasaku’s yakuza movies) this becomes less clear-cut.

When court official Kira (Nobuo Kaneko) publicly insults Lord Asano (Teruhiko Saigo), the latter draws his sword and attacks Kira, an unforgivable breach of court protocol. Despite evidence of deliberate provocation, Kira is excused while Asano is ordered to commit seppuku (ritual suicide). Despite it being generally known that this sentence was unjust, the Shogun orders the dissolution of the Asano estate, which means that the clan’s retainers will now become masterless samurai, or ronin. Although there is pressure for their leader Kuranosuke Ohishi (Kinnosuke Nakamura) to take revenge against Kira, he seems to accede to the Shogun’s orders. The embittered samurai scatter and the film follows a number of them – some make half-baked attempts at revenge, others sink into despair, and Ohishi himself seems to become dissolute. But he and a core group are biding their time and a year-and-a-half later, Ohishi leads the forty-seven in an attack on the house where Kira has sought security.

By the time we get to this protracted and bloody assault, the distance between the original offence and the ronins’ act of retribution creates a sense of futility; this is a bloody ritual rooted in customs which no longer seem to have any value and purpose. Yet the slaughter is an inevitable consequence of the samurai code – a commentary of sorts is provided by the neighbouring lord, Tsuchiya (Toshiro Mifune), who orders his own retainers to prevent anyone escaping over the wall into his own compound as Ohishi’s men call out who they are and the reason for their actions, apologizing for the disturbance as they slaughter those protecting Kira before finally dispatching the offending official.

Fukasaku’s conflict with Nakamura stemmed from the latter’s desire to treat the story with traditional reverence, while Fukasaku had a more critical perspective, in keeping with his well-established cynical view of Japanese history and the attitudes which had led to the self-destructive actions of military imperialism, which in turn had produced the post-war corruption and violence he had deconstructed in the Battles Without Honor and Humanity series and other yakuza movies. And yet Fukasaku’s style in The Fall of Ako Castle is more restrained than usual, giving the film a classical feel which masks its critique to some degree. Even Sonny Chiba, as the ronin Kazuemon Fuwa who joins Ohishi’s mission, plays the role quite straight rather than bringing the more modern, iconoclastic attitude you might expect given his well-established screen persona.

Toei’s restoration looks gorgeous and the film is supported by a Tom Mes commentary, a lengthy discussion from Tony Rayns and a video essay by Jasper Sharp.

*

Miscellaneous

Limbo (Soi Cheang, 2021)

When is style too much? This is no doubt a matter of personal taste and I’m probably no more consistent in my opinions than anyone else. I loved Blade Runner (1982) the first time I saw it because I was swept away by the density of its visual world-building. Over the years, watching it again many times, I’ve found more depth in its themes and narrative (though many still criticize it as all style, no substance). I had a similar experience with Se7en (1995) – an initial immersion in the film’s imaginative landscape, followed by an appreciation of its storytelling. Will I eventually have the same experience with Soi Cheang’s Limbo (2021), like Se7en a serial-killer story in which the detectives’ character flaws complicate the investigation?

Shot by Cheng Siu-Keung in high-contrast black-and-white, the film transforms Hong Kong into a graphic space reminiscent of manga. The streets are choked with garbage and haunted by the dispossessed and homeless, and someone is killing women in this urban Hellscape. Inexperienced cop Will Ren (Mason Lee) is teamed with veteran Cham Lau (Lam Ka-Tung) to stop the killer, but the younger man is troubled by his partner’s explosions of violence towards potential witnesses and suspects. In particular, Lau is consumed by anger towards car thief Wong To (Cya Liu), who keeps coming back to offer information despite the violence he inflicts on her. We eventually learn that some years ago, Wong killed Lau’s wife with a stolen car. Lau’s anger blinds him to her potential usefulness as a witness, while her efforts to atone expose her to retribution from the criminals she was once involved with.

Visually and narratively dense, the dazzling surface of Limbo obscures the basic mechanics of the storytelling and while its details are often riveting the story itself remains distant and abstract. I’ll eventually watch it again to see if the narrative has more to offer, but on a first viewing the style was overwhelming. That said, the film looks stunning on Capelight Pictures’ dual-format 4K UHD/Blu-ray edition, though the lack of any extras other than a text interview with the director is annoying.

*

The Giant Gila Monster/The Killer Shrews (Ray Kellogg, 1959)

From an excess of style to a mound of cheese – I couldn’t resist picking up the Film Masters two-disk set of The Giant Gila Monster and The Killer Shrews (both 1959), two drive-in quickies knocked out in Texas by Ray Kellogg. Kellogg was an accomplished optical effects technician and second-unit director whose best-known credit is probably The Green Berets (1968), which he co-directed with star John Wayne. But I won’t hold that against him, because these two ’50s monster movies are pretty entertaining, at least in part for their brazen disinterest in offering anything like convincing monsters.

The first movie uses the classic lizard-shot-in-slow-motion-on-miniature-sets composited with the actors; the second uses large dogs in shaggy coats and head masks to stand in for giant rodents. The lizard hangs out in a ravine near a small town, attacking teens who park there to make out. A local mechanic/hotrodder named Chase Winstead (Don Sullivan) has to fend off the Sheriff (Fred Graham) as he gets to the bottom of the disappearances.

Although the set gives The Giant Gila Monster top-billing, The Killer Shrews – in which the shrews have overrun a remote island where a scientist trying to solve the world’s food supply problems has been doing genetic experiments – is actually more entertaining (and more notorious). It even has a few recognizable faces in the cast – James Best as a boat captain who brings supplies to the island at just the wrong time; Ken Curtis as the scientist’s sleazy assistant who keeps hitting on the man’s daughter, who’s played by Swedish beauty-contest-winner Ingrid Goude. But strangest of all, Dr. Craigis is played by Baruch Lumet, father of director Sidney Lumet.

As the prof’s compound is besieged overnight, nerves are frayed, tempers flare and characters succumb to the pack of dog-shrews as they attempt to make it to the beach and onto the boat. In retrospect, the most troubling thing about the movie is the way the captain’s crewman Rook (Judge Henry Dupree) is so casually disposed of as the first victim of the shrews, with no one even noticing. The fact that he’s African-American makes this a classic case of “the Black guy gets it first”, with even his buddy the captain not giving him a moment’s thought.

That these two slices of very disposable entertainment should have been given relatively lavish treatment on disk is remarkable – and provides hope that other obscure, out-of-the-way movies will eventually be unearthed. In addition to surprisingly good transfers, each movie has the option of either the 1.85:1 theatrical framing, or a full-frame 1.33:1 TV version. Each also gets a commentary and radio promo spots, plus there’s a long archival interview with Don Sullivan and a featurette by Daniel Griffith on Kellogg’s career.

*

The Man Who Killed Hitler and Then the Bigfoot (Robert D. Krzykowski, 2018)

Robert D. Krzykowski’s The Man Who Killed Hitler and Then the Bigfoot (2018) is a title in search of a movie. A seeming joke, though played completely straight, it lacks a punchline. Towards the end of the War, an American agent named Calvin Barr (Aidan Turner) goes behind German lines with the help of partisans and, disguised as an SS officer, manages to kill Hitler. But this is covered up by both the Germans (who have doubles) and the Americans, so it was all a bit futile. Particularly since the secret mission cost Barr the love of his life.

Now an old man, Barr (Sam Elliott) is living quietly with his regrets when federal agents and members of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police approach him and ask him to take on another mission – somewhere in the Canadian woods, Bigfoot is carrying a deadly plague which is beginning to spread; for some reason, that wartime mission (and his ability to keep quiet about it) make Barr uniquely qualified to hunt and kill the cryptid. So he’s dropped in the woods, tracks the critter, and kills it though there’s a suggestion that it’s intelligent. There’s no link, of course, between Hitler and Bigfoot… The movie is about a sad man burdened by what he’s done in his life and what it has cost him, but the arbitrariness of the two assignments which bookend that life (and the implausibility of the first and the unreality of the second) make Barr’s emotional burden seem weightless despite Elliott’s considerable natural charm.

The Sparky Pictures Region B Blu-ray has a strikingly colourful image, supplemented with a director commentary, a lengthy making-of, deleted scenes, interview with the score’s composer and a short film by Krzykowski.

*

Haunted Samurai (Keichi Ozawa, 1970)

Nikkatsu wasn’t noted for samurai films and, from the late ’50s through the ’60s, they concentrated on youth and crime movies, shifting increasingly into pink films in the ’70s, so Keichi Ozawa’s Haunted Samurai (1970) was a bit of an oddity. Made a few years before the Lone Wolf and Cub series and Lady Snowblood were adapted by Toho from manga, it was based on the work of Lone Wolf artist Goseki Kojima and shares something of the same thematic and narrative quality.

Rokuheita (Hideki Takahashi) is a samurai with the Yagyu Clan who, in the opening sequence, kills another samurai condemned by the Clan. This is witnessed by his sister, who hates what he does and hangs herself. This makes him reject his role, and he leaves to find some other kind of life, which makes him a fugitive, himself condemned to death by the Clan. What follows is an episodic journey of self-discovery. He encounters a group of bare-breasted female ninjas whom he has to fight underwater; he takes refuge among peasants oppressed by a cruel lord; he finds a stash of gold which makes him a target of another samurai … and all the while he’s pursued by Yagyu assassins.

There are well-handled action scenes scattered through the film, but its focus is on Rokuheita and his development as a character whose conscience has been awakened. Takahashi gives an excellent performance, adding some gravitas to the occasionally pulpy narrative, and the film benefits from Minoru Yokoyama’s excellent widescreen cinematography and Hajime Kaburagi’s score.

While not pristine, the 2K scan looks generally fine and the audio is serviceable. The resurrection of this little-known film is the work of a company called Surviving Elements in collaboration with distributor Diabolik DVD, who have issued it in a limited edition (only 1000 copies) with no chance of any further pressings when it’s sold out. They’ve included a commentary from Chris Poggiali and John Charles, who provide details about the production, the source material, and the actual history of the Yagyu Clan.

*

Black Circle (Adrian Garcia Bogliano, 2018)

I’ve mentioned before why I miss the almost complete disappearance of physical stores where you can browse the shelves and occasionally make interesting discoveries – as opposed to shopping on-line where you’re mostly looking for something you already know about. I recently made one of my trips to Entertainment Exchange in the Grant Park mall to trade in a few surplus disks and while the owner was adding up what they were worth, I looked over the shelves of new Blu-rays (expanding as the used shelves have gradually contracted over the past couple of years). The store has been bringing in more releases from Britain and Australia, as well as most releases from Vinegar Syndrome and Severin, with quite a few Arrow titles as well. I picked up a couple more Radiance releases (Juanma Bajo Ulloa’s The Dead Mother [1993] and Pietro Germi’s The Facts of Murder [1959]), along with something called Black Circle (2019), about which I knew nothing, but the description hit a number of points which immediately appealed to me.

Although made in Sweden (in Swedish), it was written and directed by Spanish-born Adrian Garcia Bogliano, whose only previous work I’ve seen is the atmospheric but disappointing Mexican movie Here Comes the Devil (2012) and a segment of The ABCs of Death (also 2012). The film stars Christina Lindberg, who I know from Bo Arne Vibenius’s Thriller: A Cruel Picture (1973), as a woman whose father was involved in some esoteric experiments in the ’70s which have unexpected fallout decades later in the lives of two estranged sisters. These experiments involved transforming lives with “magnetism”, not to be confused with mere hypnosis.

The catalyst which links past and present and triggers gradually escalating creepiness is a 12″ vinyl record which Isa (Erica Midfjäll) found in a house left to the sisters by a distant relative. The record has self-help routines which are supposed to transform your life by opening up hidden parts of your mind. Isa has tried it and landed a lucrative new job, so she calls her sister Celeste (Felice Jankell) and urges her to take the record and listen to it every night for a week as she falls asleep. Although skeptical, Celeste does what she’s told and weird things begin to happen. She discovers that the daughter of the man behind the record is still alive and tracks her down.

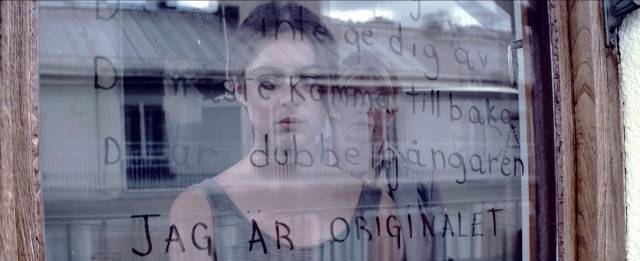

Lena (Christina Lindberg) isn’t very surprised when the sisters come calling because she’s had to deal with the consequences of her father’s research before. It turns out that the process involving the record splits the user in two, creating a doppelganger which grows stronger and eventually takes over the user’s life unless forcefully reintegrated. The second half of the movie deals with the stressful and dangerous process of reintegration – first with Celeste and then, with greater difficulty, Isa, who has been split for much longer making it difficult to tell which of the two is the real Isa and which the doppelganger.

I love this kind of story – the esoteric discovery, the unforeseen consequences, the risk of madness and death. This is the central conceit of a lot of horror (think M.R. James and H.P. Lovecraft) and when done well (and played straight) can be deeply creepy in ways which don’t require jump scares, but rather insinuate their way into your imagination and bypass the filters which normally keep out nonsense ideas. Black Circle reminds me of Andreas Marschall’s Tears of Kali (2004) and Masks (2011) and Henrik Möller’s Feed the Light (2014), all movies which use imagination to wring the most out of limited resources.

The Synapse Blu-ray has a very good transfer along with a director commentary, a brief behind-the-scenes featurette, an hour-long interview with the director and Lindberg (who was also one of the executive producers), a short film which is essentially the opening sequence of the feature, and a CD of Rickard Gramfors’ excellent score. This is one of my most satisfying recent finds.

Comments