Buddy Giovinazzo’s American Nightmares

Does it mean anything that Staten Island has produced not one but two independent filmmakers whose view of the world and human relationships is unremittingly bleak? One, Andy Milligan, was a prolific maker of ultra-cheap exploitation movies steeped in acid and bitterness; the other, Buddy Giovinazzo, has been far less prolific if no less bleak, and more concerned with the harsh effects of the social failures which constrain, distort and ultimately crush lives on the margins. In a forty-year career, Giovinazzo has made only five features, a number of short films and sketches for features for which he was unable to find financing, and after his third feature, he moved to Germany where he has taught, written novels (in English and German) and directed some three-dozen episodes of television series (including five for Tatort [1970- ], the long-running series for which Samuel Fuller made Dead Pigeon on Beethoven Street [1973]).

I first came across Giovinazzo when Troma released a 25th Anniversary DVD of his first feature, Combat Shock (1986), in 2009, quickly followed by Anchor Bay’s DVD of his fourth feature, Life Is Hot in Cracktown (2009), based on his own short story collection. Together, these two movies gave me the impression of an industry outsider working with highly personal material on limited budgets. So I was surprised when Severin released his second feature on Blu-ray in 2020; No Way Home (1996), made twelve years after Combat Shock, was a far more polished piece of work with a cast headed by Tim Roth and Deborah Kara Unger, which nonetheless shared the Staten Island setting of its predecessor and its concern with people living precariously on the fringes of society.

The Unscarred (2000)

Now Severin have released Giovinazzo’s third feature, The Unscarred (2000), which bridges his transition to Germany – early scenes were shot in the same impoverished U.S. setting as the previous films before the narrative relocates to Berlin. This is the only one of the features not written by Giovinazzo – the script is by Karl Junghans, who seems to have no other credits – though he does share a writing credit on his fifth feature, A Night of Nightmares (2012), with Greg Chandler.

While The Unscarred shares certain elements with Giovinazzo’s other films, and it remains pretty dark, it shows a sense of play not apparent elsewhere. The tightly-plotted script keeps shifting viewer perceptions, gradually revealing more details about the characters and their relationships so that our understanding of what is happening is constantly changing. By the end, we are aware that not only are the excellent cast playing particular characters, but those characters are also performing roles intended to mislead the other characters. While this could be merely a clever game – like Anthony Shaffer’s Sleuth or Ira Levin’s Deathtrap – Giovinazzo keeps it well-grounded in the narrative’s underlying class tensions.

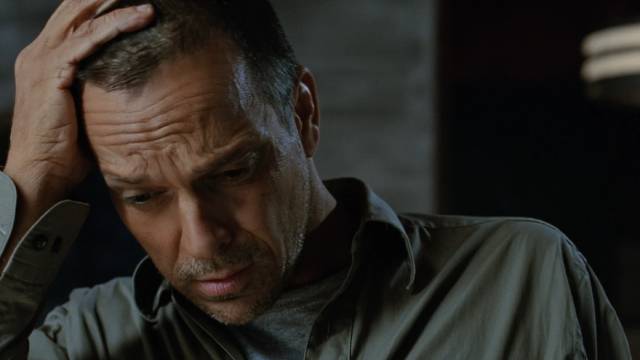

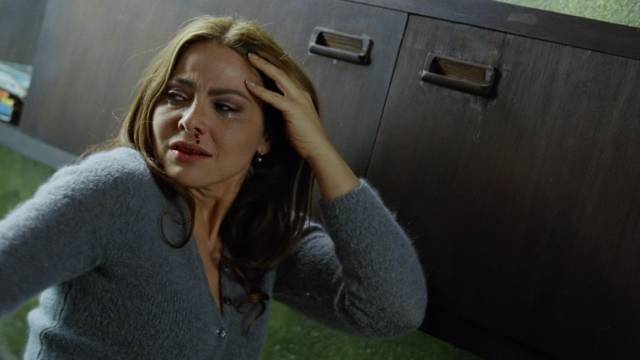

Mickey (James Russo, who played Roth’s brother in No Way Home) works a dead-end job in a machine shop in a run-down neighbourhood, the only spice in his life a serious gambling habit. He’s in deep to a local mobster who is running out of patience and if he doesn’t pay what he owes in a few days, he’s going to be very dead. At this low point, he gets a call from old college friend Travis (Steven Waddington), inviting him to a reunion in Berlin with their friends Johann (Heino Ferch) and Rafaella (Ornella Muti). Needing to get out of town quickly, he flies to Germany.

Although it’s been twenty years since they were all at university together, there are unresolved tensions stemming from an incident shown in the prologue. Mickey and Travis were involved in a drinking contest at a party, spurred on by Johann and to the disgust of Rafaella. When things get out of hand, a fight breaks out and Mickey is pushed off a balcony by Travis, his injuries putting an end to a hoped-for career in pro baseball. The working class Mickey seems to resent the others’ wealth, which serves to remind him of his own stalled ambitions.

Things take a turn for the worse after an evening at a club where Travis picks up Anka (Ulrike Haase), who returns with them to Johann and Rafaella’s expensively (and illegally) converted warehouse. After Mickey has gone to bed, he’s awakened by a scream and a crash and goes out to discover that Anka has fallen from the balcony onto a large glass table, lying down there among the shattered glass in a pool of blood. In shock, Travis says that she fell when she leaned on the railing as they headed to his bedroom. This echo of the long-ago incident at university amplifies the undercurrents; Travis is near hysteria, but both Mickey and Johann realize that they’re all now at risk because it’s unlikely the police will buy the accident story – the combination of booze and drugs and wealth will raise too many alarms. And so Mickey and Johann set about clearing up the mess and disposing of the body…

Complications arise when Mickey and Travis get lost on the way back from dumping the body into a river and they drive the wrong way up a one-way street and are stopped by the police. Mickey panics and drives away at high speed. Meanwhile Anka’s brother (Andreas Petri) has turned up looking for her and Johann has knocked him out. The three men tie him up just as the police arrive looking for the driver they were chasing … after the police leave, the brother manages to free himself and in a struggle, Johann shoots him … and just as they clean up that mess, Rafaella returns from a night away at her sister’s. This rapid accumulation of incidents almost pushes the film into the realm of black comedy, but Giovinazzo and the cast maintain the tension as we learn that there are other factors underlying the fraught connections between the characters.

Not only has Mickey been squeezing the others individually for money over their guilt for his injury; he is also the father of Rafaella’s son – she has been paying him to stay out of the boy’s life. All that money has been squandered on his gambling addiction, and now he’s demanding larger payments from each of them to stay quiet about the deaths in Johann and Rafaella’s home. This is the only way he can possibly pay off his gambling debts and save his own life, but they turn the tables and explain that together they can frame him for both deaths, that it’s time for him to get out of their lives altogether. Giving him a ticket home, they leave him at the airport, but he really can’t go home empty-handed…

But even then, the film has a couple more twists to play, leading to a downbeat ending which feels inevitable given everything we’ve learned about these characters. The game the film plays engages us even though the characters eventually all reveal themselves to be deeply unsympathetic. As in his other films, Giovinazzo shows an interest in people without passing judgment no matter what they eventually do.

Severin’s 2K transfer is excellent, supplemented with a director commentary and interviews with Russo and Ferch.

*

Combat Shock (1986)

Coinciding with this release, Severin published Giovinazzo’s new novelization of Combat Shock. This is the first of his books I’ve read and it’s piqued an interest in his other fiction, though some of his books seem to be hard to find – strangely, they seem to be more readily available in German and French than in English. It’s been years since I watched the movie on Troma’s DVD, but Severin’s limited edition Blu-ray (signed and numbered by Giovinazzo) has been sitting on my shelf for rather a long time. Now seemed like a good time to take another look.

Shot on 16mm, with a very small budget, Combat Shock, or American Nightmares as it was originally titled, is unremittingly grim. While its flashbacks to the Vietnam War are threadbare and the swampy Staten Island locations a not very convincing stand-in for Southeast Asia, Giovinazzo’s commitment to the material overcomes such limitations and the rest of the film, which takes place in a single day in an urban hellscape which suggests a post-apocalyptic wasteland rather than an area close to New York City, is grimly realistic.

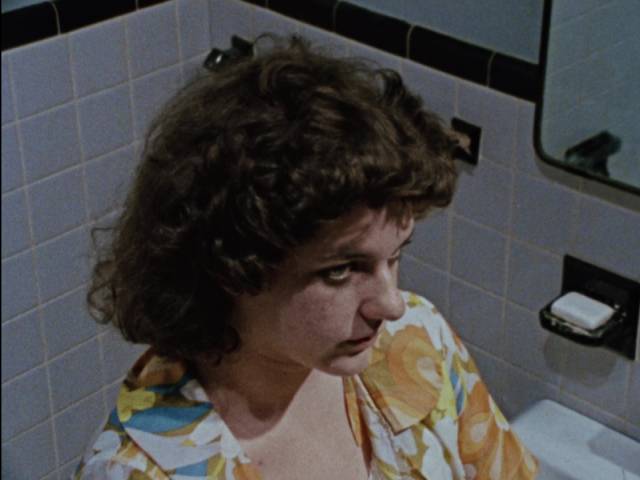

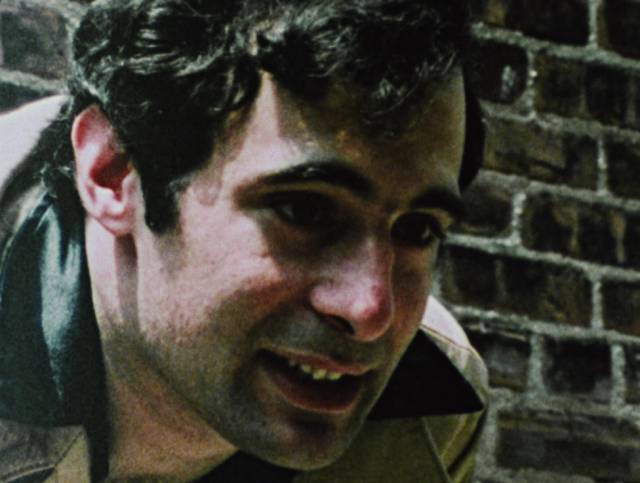

Giovinazzo has commented that the film is a cross between Eraserhead and Taxi Driver, and there are obvious echoes, but Combat Shock is very much its own thing and transforms those influences in fiercely original ways. Frankie (the director’s brother Rick, who also composed the unsettling synth score) carries so much trauma from his time in Vietnam that he’s almost catatonic. He lives in a slum apartment with his equally beaten-down wife Cathy (Veronica Stork) and a baby which is more recognizably human than Spike in Eraserhead, but it’s severely damaged, probably because of Frankie’s exposure to Agent Orange during the war. The baby’s incessant wailing is similar to Spike’s, and Giovinazzo includes a spoon-feeding moment and close-ups of a bubbling humidifier which recall moments in David Lynch’s film, reinforcing the nightmare tone of the family’s life.

In the outside world, Frankie wanders desolate streets and encounters various other people living on the edge – Mike the junkie (Michael Tierno), another junkie named Terry (Eddie Pepitone), a child prostitute, an aggressive pimp (Arthur Saunders) – a haunting collection who emphasize the hopelessness of the world he’s trapped in. He runs into Paco (Mitch Maglio) and his gang, a hood to whom he owes money (linking Frankie and his world to the later situation of Mickey in The Unscarred); he’s threatened and beaten and given only a little more time to repay his debt before Paco’s goons will do worse.

He visits the employment office, where an overworked welfare worker (Ray Pinero) has nothing to offer because Frankie has no qualifications. The aura of hopelessness permeates everything and everyone around Frankie – Mike has tried Paco’s patience to the limit and when he tries to pay for heroin with some fake jewellery he’s given a small bag of poison instead of a fix; in one of the film’s darkest scenes, having been unable to find a needle, he uses a straightened coat hanger to puncture his vein and rubs the powder into the bloody wound.

Although he has resisted Cathy’s urging, Frankie finally calls his estranged father (Leo Lunney) to plead for money. But the old man, who has believed that Frankie died in the war, is sick and crippled and broke himself. Frankie is finally reduced to mugging a woman (Mary Cristadoro) and is spotted by Paco and his thugs as he runs away with the purse; they chase him and as they beat him and grab the purse, they don’t notice that a gun has fallen out. But Frankie finds it as they check the bag’s contents and he calmly kills them all before heading home for the film’s horrific climax, in which he sees the most compassionate solution to this nightmare is simply to end everyone’s suffering.

The relentless logic of the narrative distinguishes Combat Shock from other low-budget horrors to which it seems akin – there’s none of the dark humour of Frank Henenlotter’s Basket Case (1982), for instance, and even Eraserhead had a kind of redemptive ending. There’s not even a touch of the ironic heroism of Taxi Driver in Frankie’s climactic encounter with Paco’s gang, and his twisted act of love in liberating his family from the grinding horror of their existence offers another form of horror, leaving viewers with their own vicarious trauma rather than catharsis.

Despite obvious budgetary limitations, Giovinazzo avoids most of the pitfalls faced by resource-challenged genre filmmakers; in particular, in addition to maintaining an intense and consistent tone which ultimately achieves a genuine sense of tragedy, he shows a real sensitivity to his cast, getting good or better performances from people for whom this is their only acting credit. In the case of Rick Giovinazzo, it’s strange that he hasn’t acted again because his Frankie is quite remarkable, expressing enormous levels of pain and confusion with little more than haunted eyes and a terrifying absence of affect. He embodies the way in which trauma crushes humanity out of an ordinary guy.

It seems paradoxical that the film was picked up and released by Troma, a company noted for cheap movies which wallow in and mock genre conventions. Initially cut to gain an R rating, it was promoted as a Vietnam action movie, which garnered a negative response from action fans, but was gradually discovered by horror fans who appreciated what Giovinazzo had achieved. Troma’s 2009 DVD included both the R-rated cut and the longer original American Nightmares version. Severin’s edition offers only the latter, along with most of the copious Troma extras plus a new commentary with Buddy and Rick Giovinazzo and makeup effects artist Ed Varuolo, and some new interview featurettes.

The limited edition also includes a soundtrack CD, and came with a slim book containing a diary of the production, the script and a lot of production stills and promotional material. The diary will trigger a lot of recognition in anyone who has made low-budget films, stealing shots without permits, wrangling volunteers, and trying to make something bigger and more textured from what little is available; and the script, which provides the narrative framework, emphasizes just how much Giovinazzo was able to add to the material in the shooting. As for the novelization, it faithfully represents the film and adds some additional texture by permitting the reader to glimpse some of the thoughts and motivations of secondary characters and, most significantly, makes explicit the full nature of what happened to Frankie in Vietnam and the unbearable burden of guilt he’s carrying.

Comments

I suspect Junghans and Giovinazzo are probably the same person

That certainly hadn’t occurred to me, but it’s an interesting thought. I haven’t found anything about him on-line other than this one credit.

I think he’s just (slightly mis-)translated his own surname

This is true, I wrote the filmed script for THE UNSCARRED. The original writer turned in a script that was too short and had massive holes in the story. I did a page 1 rewrite and when it came time for the credits, the original writer didn’t want to share credit. So the producer came up with a solution, which I agreed with at the time. Karl Junghans isn’t a translation of my name, it’s a completely made up name.