Sophie Compton & Reuben Hamlyn’s Another Body (2023): deep-fake porn and stolen identity

The most unsettling horror movie I’ve seen recently is actually a documentary. The situation it deals with is disturbing, while its technique raises numerous issues related to that situation which ultimately cause the viewer uncertainty about the very nature of visual media. That Another Body (2023) is the first work of two young filmmakers, Sophie Compton and Reuben Hamlyn, makes it all the more remarkable.

We are introduced to a young woman named Taylor Klein who attends college in a Connecticut town, where she’s studying for a Masters in engineering. She’s lively and engaging. And quickly informs us of something dark which casts a shadow over what initially appears to be a carefree, hopeful life. One day an acquaintance sends her a message with a link, urging her to watch the on-line video. What she sees upends her sense of herself and the world she has thus far inhabited.

The video is a porn clip which not only shows her engaged in sex, but comes complete with tags which name her and the town where she lives, along with her contact information. This immediately explains a recent surge in seemingly inexplicable messages she’s been receiving from unknown men. But so much more is inexplicable. At first, it’s hard to assimilate what’s going on and she distances herself from it. But there are multiple clips and she begins to fear not only possible consequences – what if these clips are seen by relatives or potential employers? – but also the motives of whoever has created the videos.

An attempt to interest the police is frustrating – there are no laws covering this kind of appropriation of identity; in fact, she’s told that whoever is doing it “has the right” … you know, “free speech”. But then she discovers clips using another of her classmates, named Julia, whom she contacts, and together they embark on their own investigation, attempting to figure out who the culprit is.

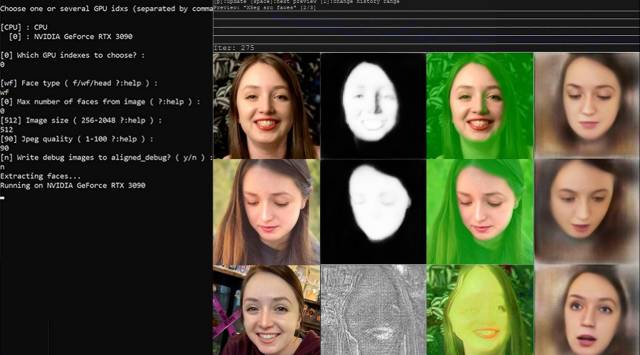

It’s here, as this begins, that the filmmakers reveal that Taylor and Julia are not real names and that the faces we see are not those of the real subjects, who have been filmed and recorded and then treated to the same deep-fake technology to replace their faces with those of actors in order to protect their true identities – and protect them from possible further victimization.

In conventional documentary terms, this raises some issues – is it actually much different from shooting subjects in shadow to hide their faces? Does it undermine the authenticity of the situation? Is it moving towards dramatization rather than documentary? But despite certain caveats, the technique adds some important thematic weight. First of all, it permits us to engage with Taylor and Julia through their actual voices and body language while leaving them unexposed; but more importantly it displays the disturbing power of deep-fake technology to appropriate individual identity seamlessly. This has come a long way since the days of The Polar Express (2004) and the “uncanny valley” effect of synthesized human faces.

To illustrate and emphasize this point, the film includes CG animation as the investigation continues and Taylor and Julia home in on the probable identity of the person attacking them. It’s here that the film broadens out into a wider context within which the deep-fake attacks are occurring. These women’s experience in the still predominantly masculine environment of the engineering program is suffused with sexism and misogyny which is taken for granted. What isn’t expected is the realization that their victimizer – whom they discover has also targeted a number of other women from their college cohort – is someone who had been a friend, living close in their dorm, who had come to them for emotional support.

This dynamic, of men who rely on women emotionally while apparently harbouring aggressive sexual fantasies about them, is disturbing … the idea that those fantasies can now be directed towards conceptual violence through AI tools rather than acted out in the world may initially seem preferable, but the technology actually has a disinhibiting effect; in this case, while their “friend” hasn’t resorted to rape to get revenge for what he apparently sees as rejection (Taylor wasn’t always emotionally available when he needed a sympathetic listener), his psychological and social assaults nonetheless have potential for causing far-reaching, lasting damage.

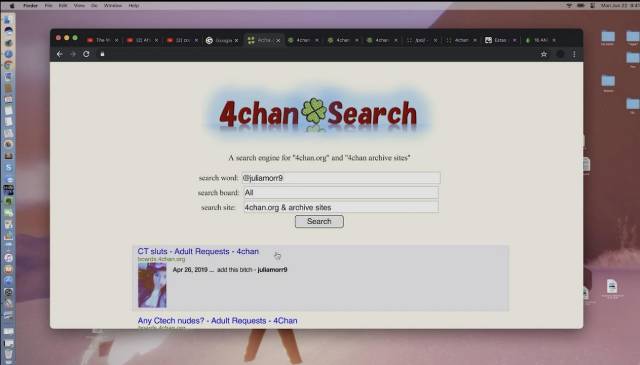

Paradoxically, Taylor herself provides a counterweight to this depressing prospect. Her determination not to be crushed by these attacks and her efforts to solve the “mystery” lead her – and Julia – deep into very unsavoury areas of the Internet and a disturbingly large community of creeps producing this deep-fake porn to vent their rage on women who, for the most part, probably don’t even know they’re targeted. There are endless message boards where photos and personal information are posted with the posters’ requests for personalized porn scenes using these women. It’s in this environment that the probable identity of Taylor’s own victimizer emerges, along with the identities of multiple other victims.

Among the latter is a YouTuber who goes by Gibi ASMR, whom Taylor contacted and who eventually went public as a victim of this deep-fake culture, helping to push the issue into public discourse; although there are still no specific laws covering what has become a pervasive sexual crime, there have now been hearings and discussions in political circles. The film ends with a note explaining that there are now hundreds of thousands of victims – the presence of deep-fake porn using well-known women (actors, politicians, newsmakers) has become so common as to be an almost accepted price for fame, but there are also countless ordinary women, like Taylor and Julia, who are being targeted, and in those cases the men targeting them are more likely to be close in real life.

Once Taylor was certain who has been targeting her, she passed the information along to the police who, again, had no legal recourse but did call him and let him know he’d been identified, suggesting that he stop what he’s doing. But with no real consequences, and a job in the tech industry, what’s the likelihood that the women he works with are now being targeted, while having no idea what their co-worker is really like? Armed with sophisticated digital tools, these creeps are expanding rape culture into new dimensions which government and law enforcement are ill-equipped to address in any meaningful way. In collaboration with the filmmakers, Taylor has helped to illuminate this dank world in a way which makes the issues clear and urgent.

For a film which uses a lot of Zoom video and digital effects, Another Body doesn’t seem limited or contrived, thanks in large part to the engaging personalities of Taylor and Julia and the impressive editing skills of Isabel Freeman and Rahab Haj Yahya. The Utopia Blu-ray includes a director commentary along with several interviews and Q&As recorded at festival screenings.

Comments