Recent releases from the BFI

It’s been a while, but I recently dipped into some new releases from the BFI. My order was prompted by the release of volume three of Short Sharp Shocks, another collection of short films compiled under the banner of the Flipside sub-label.

Short Sharp Shocks Vol. 3 (Various, 1951-85)

This is once again a mixed bag, like the previous sets, including some polished work by professionals as well as student films and public service spots. At times ambition stretches limited resources close to the breaking point, but ingenuity often triumphs over technical constraints. Of the eleven pieces spread across two disks, the only one I’d previously encountered is Return to Glennascaul (1951), a side project written and directed by actor Hilton Edwards during a break in filming Orson Welles’ Othello. Welles plays a version of himself, recounting a recent experience when, driving home one foggy evening in Ireland, he picked up a hitchhiker who told him an odd story about himself picking up a couple of stranded women on such a night and taking them to an elegant mansion where they invited him in for a drink. Following a well-trodden narrative path, it turned out that the house had been long abandoned and the two women long dead. Playful and amusing, the twenty-three-minute film has the nostalgic charm of a fireside tale, with Welles an engaging raconteur.

Strange Stories (1953) is a pair of short films with a wraparound sequence, originally intended as episodes of a proposed television series for the American market, but combined and released as a B feature in British cinemas. Two friends, actors Valentine Dyall and John Slater, delay one another by telling the two stories, each directed by a different filmmaker fairly early in a long career. Most interesting in John Guillermin’s The Strange Mr. Bartleby, which was the first adaptation of Herman Melville’s novella Bartleby the Scrivener, though barely recognizable if not for the character name and the distinctive phrase “I would rather not” which he says when asked to do anything by his employer. Lawyer Gillkie (Norman Shelley) is asked by a young woman (Naomi Chance) to find a man named Swain, his investigation leading to the derelict Bartleby (John Laurie), a broken man haunted by his past.

In Don Chaffey’s The Strange Journey, adapted from an EF Hornung story, accountant Charles (Colin Tapley) accidentally kills his employer and flees with his wife Marie (Helen Horton) on a freighter bound for Tasmania. As the only passengers, they spend a lot of time with Captain Breen (Peter Bull) and Charles’s guilty conscience eventually leads him to believe that the Captain knows what he has done and is cruelly playing with him. The best thing here is the enigmatic performance of Bull, a distinctive presence forever associated with his role as the Russian ambassador in Dr. Strangelove (1964).

Strange Experiences (1956) are a pair of brief anecdotes from a series of fillers made for Britain’s first commercial network, ITV. Host Peter Williams narrates from his armchair two stories about seemingly haunted objects – a portrait of a sea captain and a clock – each incident fleshed out with stock footage, with the addition of a couple of uncredited actors in the second tale.

Bob Bentley’s Maze (1969) was an art school project and it shows. Drawing on the allusive qualities of the New Wave, it offers glimpses of a number of characters whose paths cross randomly. With its often evocative black-and-white imagery, it creates a mood which suggests there’s more here than we’re actually seeing, hinting at a larger narrative that remains inaccessible. With a hotel dishwasher, an upper-class man and a woman who seems to exist more as an idea of the female than as an actual character, issues of class and gender are suggested but they aren’t explored – it’s a promising student film which displays Bentley’s grasp of technique, though the content is frustratingly vague.

The second disk opens with a more substantial exploration of technique. In fact, Tony Bicât’s Skinflicker (1973) is prescient in its use of “found footage” tropes years before they became a familiar mainstream phenomenon. Its approach also prefigures the use of media as a tool to promote political protest in the face of a monolithic information landscape. The tension inherent in its project is emphasized by an opening title which states that what we are about to see has been suppressed by the authorities and is to be viewed only as a training tool for police. This suggestion that the powers-that-be believe the material is too dangerous for public consumption indicates an uncertainty about the effect the footage would have on “impressionable” minds – it also recalls the controversy surrounding Peter Watkins’ The War Game (1965) eight years earlier, when it was deemed too dangerous to risk provoking the public to question the establishment’s policies about the Bomb.

In Skinflicker, three would-be revolutionaries decide to kidnap a government minister and execute him. But this act has a built-in performative element, because they will film everything and provide a running commentary about their motives. For this, they hire a cameraman whose primary experience is shooting porn; for him it’s a job for hire. His presence is foregrounded, because they also have an 8mm camera and we repeatedly see one or another camera caught in the frame. Despite the supposed political motives for the plan, the presence of the cameras transforms the members of the cell into a cast, playing their revolutionary parts for the camera. This influences their behaviour – one of the group can’t resist hamming it up and becoming increasingly abusive to their prisoner, an actor in an improv drama which becomes its own thing rather than a record of the event they have set in motion.

Director Bicât and writer Howard Brenton came from a theatre background; it’s remarkable that they should have come up with something this original in their first film, though the jagged, improvisatory quality no doubt draws on their experience with experimental theatre. The concept required the actors to operate both cameras as they were covering the entire space of the garage set where most of the action takes place, with Bicât leaving once things were set in motion. The cutting between 16mm black-and-white and 8mm colour film adds to the sense of authenticity, while the experienced cast manage to give an impression of untrained naturalism.

Broken Bottle and Don’t Fool Around With Fireworks (both 1973) are a pair of PSAs, under a minute each, about the dangers of injury to children through carelessness – in the first, a boy runs around a beach where someone has tossed a broken bottle; in the second, kids playing with firecrackers accidentally blind a girl.

Geoff Lowe’s The Terminal Game (1982) was his thesis film at the National Film School (shot in 1979), yet another prescient film which was greeted with confusion by those in charge. It’s the clearest instance in the set of ambition stretching resources to their limit, a low-budget 16mm project tackling a complex – and at the time very novel – subject. At the end of the ’70s, before the explosion in personal computer technology, AI was still very much a futuristic sci-fi concept and Lowe can only suggest the full implications of his story.

The Invex Corporation is a proto-global computer company which is developing hardware and software to surveil and control society. When Paul Mallory (John Francis) dies mysteriously while investigating the company, his colleague Raymond James (Jack Galloway) and his wife Carol (Stacy Tendeter) try to find out what happened and discover that the Invex system has become sentient and has plans of its own. On a shoestring, Lowe bridges the gap between Colossus: The Forbin Project (1970) and Skynet and finds yet again that our own technological advances will eventually see us as extraneous to their own interests. In the forty years since Lowe made the film, what was confusing to viewers back then seems obvious now. Perhaps if he had had the means to make a feature back then, it would now be seen as another landmark in our progress towards the AI apocalypse.

Nichola Bruce and Michael Coulson met at art school and began collaborating on painting projects. Influenced by punk and, particularly, William Burroughs, they transformed a series of paintings into Wings of Death (1985), an impressionistic film which evokes that chaotic time, steeped in drugs and rebellion and a self-destructive nihilism. A heroin addict (Dexter Fletcher) retreats to a rundown hotel in a decaying urban area and descends into a personal, hallucinatory hell as he plummets towards death. There are brief flashbacks to a happier time with his girlfriend (Kate Hardie) and encounters with a girl from the next room who may or may not be real. The filmmakers’ experience as artists shows in the rich production design – reminiscent of Caro et Jeunet and Terry Gilliam – and the strikingly colourful cinematography of Gale Tattersall, who had previously shot Bill Douglas’ My Ain Folk (1973) and would shoot Douglas’ masterpiece Comrades (1986) immediately after this.

The set also includes lengthy interviews with Bob Bartley, Tony Bicât, Geoff Lowe, Nichola Bruce and Michael Coulson, as well as a brief interview with composer Colin Towns on his score for The Terminal Game, a short visual essay by Vic Pratt about Vandyke Picture Corporation, the company which produced Strange Stories, and some 8mm behind-the-scenes footage from the Wings of Death shoot.

*

Brainwashed: Sex-Camera-Power (Nina Menkes, 2022)

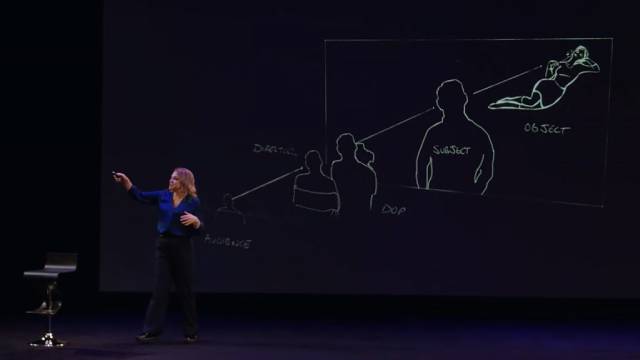

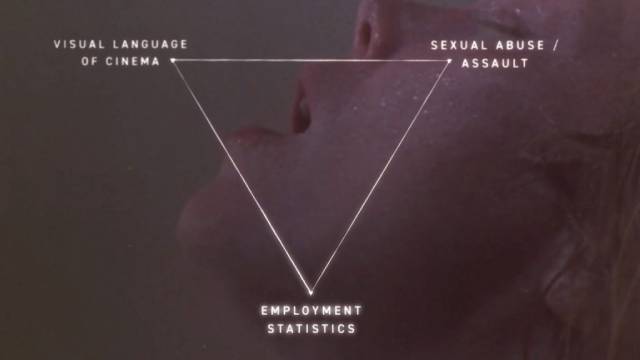

As a form of discourse polemic, by its nature, tends to be over-emphatic, simplifying the issues being addressed in order to be the more persuasive. Its aim is to shift opinions, to some degree by brute force. This is certainly true of Nina Menkes’ Brainwashed: Sex-Camera-Power (2022) which proposes, after Laura Mulvey’s seminal 1973 essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema”, that cinema itself is deeply gendered – that Mulvey’s concept of the “male gaze” is built into the visual codes of narrative filmmaking. This in turn has embedded sexism and abuse into the industry which creates movies. There’s no denying the history of abuse – from the archetypal “casting couch” on which aspiring (and established) women have historically been forced to submit sexually to powerful men to the suppression or outright exclusion of women from the business.

Built around a lecture given by Menkes at CalArts, in which she asserts her points forcefully, the film incorporates interview clips from a variety of women – studio executives, actors, filmmakers – along with clips from “over 175 movies”, which is a lot to pack into 107 minutes. The momentum carries you along, and clip after clip confirms the point as Menkes dissects the entire apparatus by which cinema constructs meaning – working her way from the individual framing of a shot to the juxtaposition of shots, patterns of editing, narrative construction, the use of sound … how can you argue with all the evidence?

And yet, when it’s over and you can catch your breath, questions begin to surface. We’ve been shown brief clips from a couple of hundred movies out of the hundreds of thousands made since 1896, clips extracted from all narrative context and framed by Menkes to make us see them as monolithic in their meaning. She skims over the many women who held influential positions during the silent era, as writers, directors, editors and producer-stars; it’s undeniable that with the coming of sound, many of these women were pushed aside – women’s role was largely relegated to that of on-screen object, which definitely helped to consolidate the male gaze, but the elision of the female presence in the first three decades of cinema clouds the idea that the male gaze was not necessarily the only and inevitable mode available.

Additionally, a couple of shots from a movie in which men definitely objectify a woman are required to stand in for so many more movies in order to generalize from that specific instance. As the lecture proceeds, Menkes seems to begin suppressing counter-arguments in order to maintain her thesis – her dismissal of Kathryn Bigelow’s Best Picture and Best Director Oscar wins for The Hurt Locker (2008) by asserting that it’s just a movie about men blowing up men and was mostly made by men is in itself an erasure of a powerful woman in the business, and refuses to consider that the film’s deconstruction of masculinity is itself a sign of a female perspective on dominant attitudes. Might there not be other fissures in her argument which are being glossed over in order to support her case?

And yet, while Menkes’ assertiveness and her simplifications of a rich and complex history raise questions, there’s still value in her argument. It’s always useful to urge for a more conscious approach to the media we consume, to think about long-term, often unquestioned attitudes. In the past few years, the unsavoury exploitation of women in the industry has been brought to light by the #MeToo movement, but Menkes’ desire to make her case leads her to ignore a lot of changes which have occurred since Mulvey first wrote about the male gaze. Many films which were popular and influential in their own time are now widely seen as problematic – just think John Hughes’ teen comedies, or countless instances of rape jokes (Revenge of the Nerds, for instance), or previously unexamined instances of toxic masculinity which now produce deep feelings of discomfort (I’ve long considered Bob Fosse’s All That Jazz [1979] a masterpiece, and one of my favourite films, but found Fosse’s self-portrait as genius choreographer Joe Gideon [Roy Scheider] almost unbearable the last time I watched it six years ago). This on-going process of re-evaluation makes Menkes’ polemic less revelatory than it might have been a decade ago, but it nonetheless has some value in prodding consumers of popular media to view what they’re watching with a more critical eye.

The Blu-ray includes a commentary from Menkes and editor Cecily Rhett and a half-hour conversation with Menkes following a screening at the BFI in 2023.

*

I’ll look at a couple more BFI releases in my next post…

Comments