Spring 2024 viewing, part one

Spring has been arriving with frustratingly erratic shifts in weather – warm and sunny one day, cold with wet snow the next – and I’ve been distracted by a torn meniscus in my left knee, which is stiff and painful most of the time. I’ve been feeling an odd mix of restlessness and lethargy, and the new disks keep rolling in and demanding attention I’m not fully equipped to give at the moment. In a single week, I received big orders from Vinegar Syndrome, Unobstructed View, Indicator and Diabolik, plus my monthly package from Criterion with another disk to review. And there are outstanding preorders from ViaVision in Australia and Cauldron in the States. No matter how I try to curb my on-line buying, it remains a losing battle.

It’s impossible to keep up and the growing stack of unwatched disks constantly nags at me – and I’ve lately been sidetracked by streaming (something I’ve steadfastly resisted until now) because a friend gave me a Roku and one of my co-workers has his own Plex channel and can grab pretty much any title I throw at him in a matter of minutes. A friend and I watched the ten-part miniseries The Terror over several nights (frustrating), and I’ve finally seen Denis Villeneuve’s Dune and Dune 2 (have to mull that one over for a while), as well as Dan Trachtenberg’s Prey (2022) and Colin and Cameron Cairnes’ Late Night with the Devil (2023), both interesting if not entirely successful variations on genre staples. I also spent two evenings watching Jason Statham in David Ayer’s The Beekeeper (2024) and Guy Ritchie’s Wrath of Man (2021), along with Nicolas Boukhrief’s Le Convoyeur (2004), the French film the latter was based on.

I did finally finish watching Network’s massive twenty-disk Edgar Wallace Anthology, fifty-four one-hour B-movies, which I started watching in January last year and continued to dip into occasionally over the ensuing fifteen months. Perhaps the initial nostalgic jolt I felt back at the beginning gradually dwindled, but I enjoyed them all.

As always, genre dominates what I’ve been watching, with some interesting discoveries and occasional disappointments.

*

Vinegar Syndrome

Vinegar Syndrome continues to expand the range of what they release, although the core remains exploitation with international titles dominating domestic releases. Andrew Lau’s A Man Called Hero (1999) was one of a number of epic martial arts fantasies made in the years after Hong Kong reverted to Chinese control; based on a comic book and relying on special effects more than traditional martial arts techniques, it’s colourful pulp which aims for an international audience with its setting in 1930s America. Francis Megahy’s Red Sun Rising (1993) is an American variation on a more contemporary martial arts story, starring kick-boxing champion Don “The Dragon” Wilson as a mixed-race Japanese cop who goes to the States in search of the yakuza who killed his partner. The story is routine, with “humour” coming in the form of a stream of racist cracks from the local cop assigned to watch him, a woman who herself is subject to constant sexist comments from her fellow cops. A fantasy element is introduced with a yakuza assassin who has the mystical power to kill with a single touch.

The company went fairly mainstream with a 4K restoration of Freddie Francis’ Dr. Terror’s House of Horrors (1965), the first of the Amicus horror anthologies. It established the formula which sustained the company into the ’70s – a cast of recognizable faces in a series of short horror stories which echoed the ironic horror comics of the ’50s, wrapped up in a frame which didn’t necessarily make sense, but provided a degree of coherence. Here, a group of passengers are joined in their train compartment by a mysterious man who uses a Tarot deck to tell their fortunes – all of which is undermined by the final revelation that they’re all already dead (and their card-wielding companion is Death himself). More charming than scary, it’s briskly directed by Francis and the cast headed by Peter Cushing and Christopher Lee is a pleasure to watch.

A more unexpected choice was Henry Hathaway’s 5 Card Stud (1968), a western which plays somewhat with the form – made the year before Hathaway’s True Grit (1969), which won John Wayne his Oscar, vied with Sam Peckinpah’s genre-transforming The Wild Bunch. The cast might have shown up in one of Howard Hawks’ late westerns – Dean Martin, Robert Mitchum, Inger Stevens, Denver Pyle, Whit Bissell – but Roddy McDowall and Yaphet Kotto signal a break from tradition and the story, scripted by veteran Marguerite Roberts (who had been blacklisted for refusing to name names to the House Committee on Un-American Activities in 1952), has elements of mystery which nudge it towards giallo territory. After a card game ends with angry players pursuing and lynching a man who was apparently cheating, someone begins killing members of the lynch mob in gruesome ways. Casting alone points towards the identity of the avenging killer, but the game of deadly cat-and-mouse is effectively handled by Hathaway and the cast. McDowall as the leader of the lynch mob is seen as miscast by some commenters in the disk extras, but I rather liked his weaselly creep who manipulates everyone around him, using others’ inherent racism to shift suspicion to Kotto’s good-natured bartender.

Alan Beattie’s The House Where Death Lives (1981) is one of those movies which seem to have been made at the wrong time. By 1981, the slasher era was getting under way, but while the story involves a series of killings (with victims bludgeoned rather than stabbed or hacked) it has the air of an early ’70s made-for-television mystery – with one big unresolved narrative question hanging over it. Nurse Meredith Stone (Patricia Pearcy) arrives at the house of wealthy invalid Ivar Langrock (Joseph Cotten) where she’s immediately suspicious of a locked room – inside which is Ivar’s insane son Wilfred (Patrick Pankhurst). His other son, a member of some hippy cult, recently died and his teenage grandson Gabriel (John Dukakis) comes to live in the house. He’s a creepy kid who hits on Meredith and plays with animal traps. Soon the family dog dies in a trap and the insane son is clubbed to death and thrown out of a second-storey window. While suspicion is obviously directed towards Gabriel, there’s definitely something odd about Meredith and after a few more violent deaths the big reveal comes as no real surprise. Beattie tries for a slow build of psychological suspense, but the movie too often feels enervated. He only directed one other feature, a vigilante movie called Stand Alone (1985, starring sixty-six year-old Charles Durning as a World War Two vet who takes on neighbourhood drug dealers), before turning to producing – his last credit was Peter Berg’s The Rundown (2003), starring Dwayne Johnson.

The double-feature set of Specters (1987) and Maya (1989) seemed promising, with both unleashing ancient supernatural entities on the modern world – the first in Rome, the second in Mexico. Unfortunately, in the hands of co-writer/director Marcello Avallone both are clumsy and sluggish and populated by characters who stubbornly remain uninteresting as they tackle the evils they inadvertently unleash. The (partially) saving grace of Specters is the presence of Donald Pleasence as an archaeologist in charge of a dig in Rome who can fill us in on the Emperor Domitian and a death cult which served some nasty god. Pleasence could raise the lamest material a notch of two, as he does here. As for Maya, the most notable member of the cast, William Berger, unfortunately dies in the opening sequence, leaving his daughter Lisa (Mariella Valentini) and a guy named Peter (Peter Phelps) to figure out what angry Mayan king Xibalba is up to. Maya is marginally better than Specters, but neither is particularly good even as pulp horror.

Piero Regnoli’s The Playgirls and the Vampire (1960) was released the same year as Mario Bava’s Black Sunday and Giorgio Ferroni’s Mill of the Stone Women, indicating that the Italian Gothic didn’t take any time slipping into sleazy exploitation. Like Renato Polselli’s The Vampire and the Ballerina (1960) and The Monster of the Opera (1964), Regnoli’s movie has a group of showgirls taking shelter in a gloomy castle whose halls are prowled by a vampire – who, in this case, notices a resemblance between one of the dancers and his long-lost love. As the night unfolds, the showgirls perform striptease and roam about in negligees. Flesh is exposed and necks are bitten. Regnoli directed only intermittently, concentrating on writing (an early credit was I Vampiri [1957], which he co-wrote with Bava and Riccardo Freda), racking up more than a hundred credits on westerns, gialli, poliziotteschi and zombie movies for the likes of Lucio Fulci, Umberto Lenzi, Mario Bianchi and Andrea Bianchi.

Spanish Blood Bath follows on the heels of Villages of the Damned, unearthing three more unknown Spanish horror movies from the ’70s. Two are from well-known directors, the third by someone unfamiliar to me. Night of the Skull (1974) is an atypical effort from Jess Franco, who by this time was already well into the perverse, fetishistic movies he’s best-known for; an old-fashioned old dark house story (the setting appears to be Victorian England, though some references suggest 19th Century Louisiana), with a script vaguely attributed to stories by Edgar Allan Poe and/or Edgar Wallace, it has a figure in a skull mask picking off members of a family gathered at a gloomy mansion for the reading of a will. The relationships are convoluted, motives murky, and Franco shows only a casual interest in the proceedings (as he did later with his slasher Bloody Moon [1981]), as if just wanting to show producers that he was capable of turning out a conventional genre movie, though his interests certainly lay elsewhere.

I’m slowly discovering the films of Jorge Grau, whose Living Dead at Manchester Morgue (1974), which has been a favourite since I first saw it on VHS sometime in the ’90s (and subsequently bought several times on disk, beginning with Anchor Bay’s limited edition tin box in 2000 and most recently Synapse’s 4K restoration). His zombie masterpiece continues to overshadow his other work, but his riff on the Countess Bathory story, Blood Ceremony (1973), is quite good, and his contemporary thriller Hunting Ground (1983) even better. The feature included in the new Vinegar Syndrome set, Violent Blood Bath (1974), is a psychological thriller with some giallo overtones. A severe judge vacationing with his younger wife finds himself drawn into a series of brutal crimes which echo those of murderers he has previously condemned to death. The film benefits from the presence of the great Fernando Rey as the judge and Marisa Mell as his wife, as well as excellent cinematography by Fernando Arribas, although if you’re familiar with the Guy de Maupassant story on which Grau and Juan Tébar based their script the big narrative twist might not come as a surprise. (That story was also one of the sources for the minor Vincent Price movie Diary of a Madman [1963].)

I hadn’t come across director Pedro L. Ramirez before seeing The Fish with the Eyes of Gold (1974), but this, which was his second-last movie, is an efficient Spanish giallo in which a drifter (Wal Davis) arrives in a small seaside town to visit an old friend and finds himself the chief suspect in a couple of brutal murders. Well-made, with a decent cast and some fine use of locations, it’s an effective mystery if not particularly original.

*

Umbrella Entertainment

I picked up a couple of older disks from Umbrella plus one new release. I haven’t re-watched the Spierig Brothers’ Undead (2003) yet – I didn’t actually like it much when I first saw it on Anchor Bay’s 2005 DVD, but I have liked their subsequent movies (Daybreakers [2009], Predestination [2014], Winchester [2018]) and since it was on sale I figured I’d take another look. I did watch John D. Lamond’s Nightmares (1980), though. After a couple of Mondo documentaries and the softcore Felicity (1978), Lamond aimed at something more mainstream with this attempt to emulate Italian gialli and American slashers. Having been traumatized as a child by a car crash which killed her mother, a young woman (Jenny Neumann) grows up with ambitions to be an actress. She gets a part in a bad play (directed by Max Phipps, who the following year would show up as The Toadie in The Road Warrior), begins a relationship with another cast member, and finds herself surrounded by an escalating pile of bodies as actors and crew members are picked off by a killer wielding pieces of broken glass. The biggest problem is that the killer’s identity is so obvious that the use of the point-of-view stalk-and-slash technique is a pointless affectation (note to filmmakers: if you don’t want the audience to know who’s doing the killings, don’t give the unseen figure obvious flashbacks belonging to your protagonist). The fumbled mystery element undermines some effective atmosphere and otherwise fairly well-staged moments of violence.

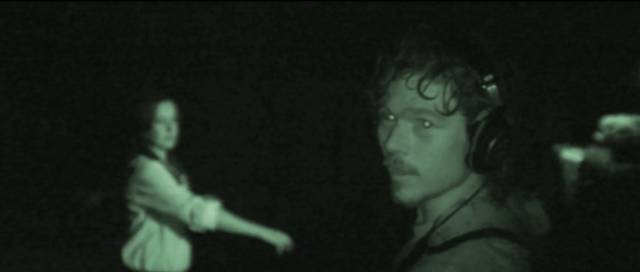

Although it’s not easy to defend against its many detractors, I still kind of like the found-footage genre – I’m ever-hopeful that someone will pull it off without succumbing to the many pitfalls, and was pleased to find that Carlo Ledesma’s The Tunnel (2011) is almost flawless. It’s not particularly original – there are obvious echoes of Gary Sherman’s Raw Meat (1972), Douglas Cheek’s C.H.U.D. (1984), and even Neil Marshall’s The Descent (2005) – but it has well-drawn characters and, perhaps most importantly, a terrific location. The fact that Ledesma and writer-producers Enzo Tedeschi and Julian Harvey have also succeeded in a plausible reason for the characters to keep filming themselves as things go from bad to worse makes this one of the best found-footage movies I’ve seen in a while.

The setting is a network of tunnels beneath Sydney, tangentially connected to the subway system, used as shelters during the Second World War and now being considered as a reservoir for the city. But that plan has suddenly been put on hold amid rumours that homeless people have been disappearing down there. Television reporter Natasha Warner (Bel Deliá) wants to do a story on the disappearances to redeem her reputation after a recent (unspecified) career misstep. She persuades her producer to give her a crew, but the authorities refuse permission to go into the tunnels. She conceals this from the crew and finds a way for them to sneak in – a deception which will soon cause problems because once they run into trouble she has to reveal that no one knows they’re down there.

The early stages engage with their exploration of the grim, dank tunnels and the sense of disorientation as they go deeper into the maze. And then something grabs the soundman and they realize they’re not alone, that whatever has been taking the homeless people who seek shelter underground is now stalking them. The film is carried a long way by the escalating friction among the remaining members of the team and there are creepy glimpses of what’s preying on them … but as with so many found-footage movies, it’s ultimately impossible to reveal the full nature of the menace because the characters themselves don’t have access to that information. What we glimpse is humanoid, but is it human or something else? A mutant? Some unknown species? For all the film’s other strengths, this leaves a vague feeling of dissatisfaction.

Among those strengths is the use of documentary techniques to frame the raw footage shot by the crew during their ordeal – this opens the film up more than is usual in the genre, with the survivors providing retrospective interviews, along with newsreel material to sketch in the historical and political context of the tunnels and their potential use.

The disk includes a mass of supplementary material which provides an interesting look at the background of the production as one of the first crowd-funded features – the producers pre-sold individual frames for $1 to fund the project, then when it was completed made it available free on-line, which seems counter-intuitive from a business point-of-view, though the film eventually got some theatrical play and this disk release.

*

Kino Lorber

I don’t think I’d ever seen William Wyler’s The Big Country (1958) before picking up the Kino Lorber Blu-ray. Wyler seems like an unlikely choice for a western, so it’s not surprising to find that this sprawling (almost three-hour) epic is more family drama and exploration of the morality of violence on the frontier than horse opera. A sea captain (Gregory Peck) arrives from the east intending to marry the daughter of a wealthy rancher. He’s met with contempt by the men’s men of the range who see him as foolish and effete. In particular, the foreman of the ranch resents his presence and constantly tries to expose him as unworthy of the boss’s daughter. The captain quickly realizes that his intended is a spoiled brat and turns his attention to another woman who’s caught between the rancher and the head of a more disreputable clan because she owns the land through which the only local water supply flows. As tensions escalate towards a range war, the captain attempts to use his intelligence and diplomatic skills to resolve the conflict without violence, in the process replacing lawlessness with a more civilized sense of shared communal interests. As skilfully crafted as all of Wyler’s movies, The Big Country offers a rational counterpoint to the genre’s easy dependence on black-and-white morality and quick resort to brute force. And of course, the cast is excellent, with Peck part of an impressive ensemble which includes Jean Simmons, Carroll Baker, Charlton Heston, Burl Ives, Charles Bickford, Chuck Connors, and Alfonso Bedoya.

There must have been something in the air – or water – in 1989. As James Cameron worked on his technically ground-breaking The Abyss, Sean S. Cunningham whipped out DeepStar Six while George Pan Cosmatos made Leviathan. In contrast to Cameron’s aliens, who had come to Earth to fix Ed Harris’s troubled marriage by making his estranged wife Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio realize that her place was with him rather than wasting her time on her silly career, the two cheaper movies went for simple monster action. DeepStar had a giant angry lobster, but Leviathan tried to replicate The Thing underwater as the crew of a sea-bottom mining facility are contaminated by a Russian biological experiment designed to transform people into human-fish hybrids. With an inadequate budget, Stan Winston’s effects team couldn’t match the achievement of John Carpenter’s masterpiece, making the monster a bit underwhelming. The script by Jeb Stuart and the sometimes brilliant David Webb Peoples (Blade Runner [1982], Unforgiven [1992], Soldier [1998]) basically tosses a bunch of genre elements into a blender, while a pretty good cast (Peter Weller, Richard Crenna, Amanda Pays, Hector Elizondo, Meg Foster) go through their cliched paces without breaking much of a sweat.

*

To be continued…

Comments